From the gnarled trachea, baroque ironwork turns capillaceous, inscribing a flat duo-headed torso in liquid iron Rorschach that curls over the shoulder and eddies into the nipple, its flurries metallizing the torso into architectural vessel. From the biceps, two yawning stairways beckon little white-socked policemen; within the warren another takes the stairs while two other policemen play on the extended jawline of the silver fortress. Justin Fitzpatrick’s painting Palazzo Police-O (2019) disorganizes corporeal and symbolic institutional structures with a touch of cocked-hip sass and panache (J and F make sly cursive winks among the ironware), compounding the intrinsic complexity of our existence within concrete, immaterial, and invisible systems. Such friction holds Palazzo tight: a cyclopean, panoptical eye surveys the composition, stately and monolithic, the green geode of its iris articulated like the folds of a Renaissance ruff.

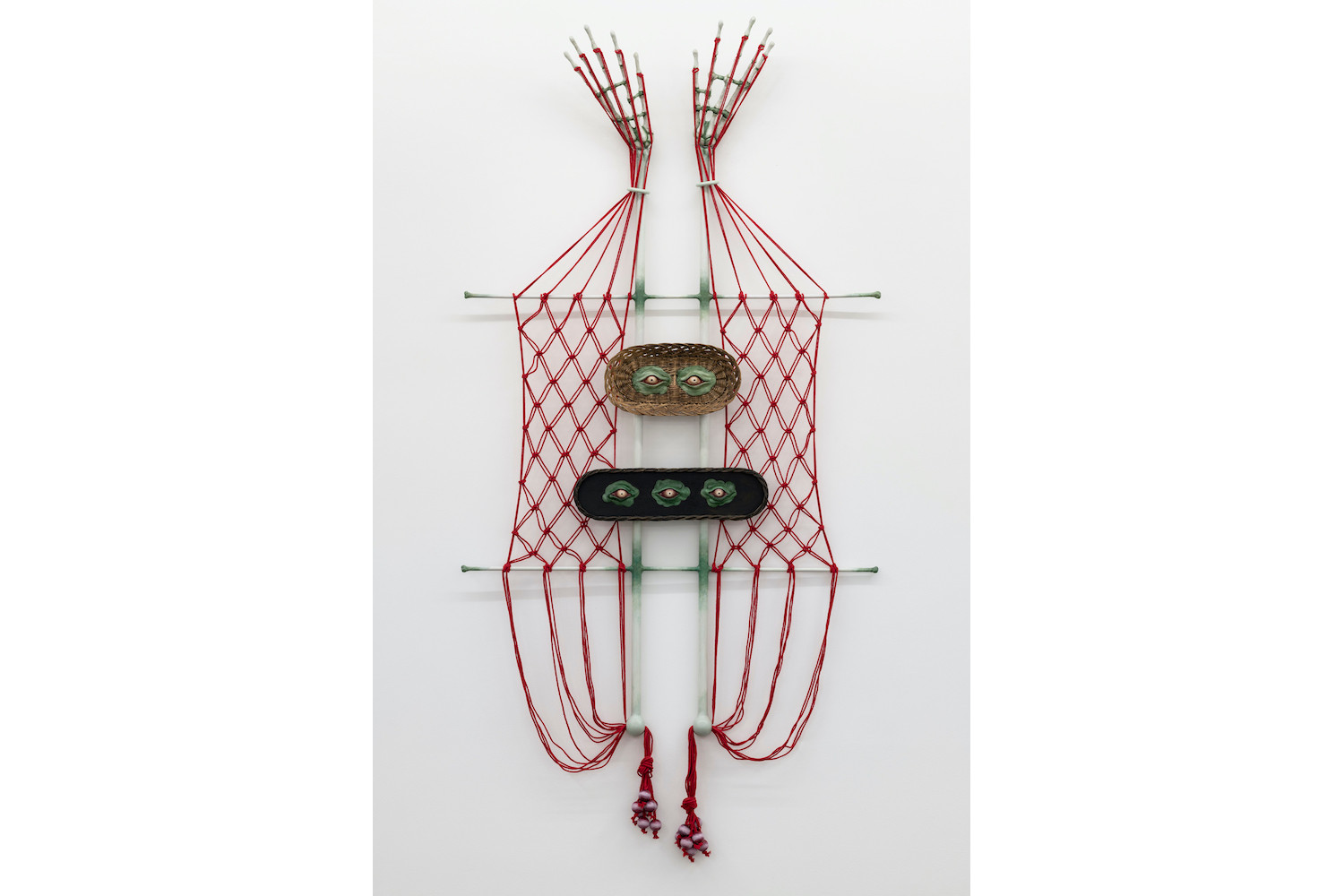

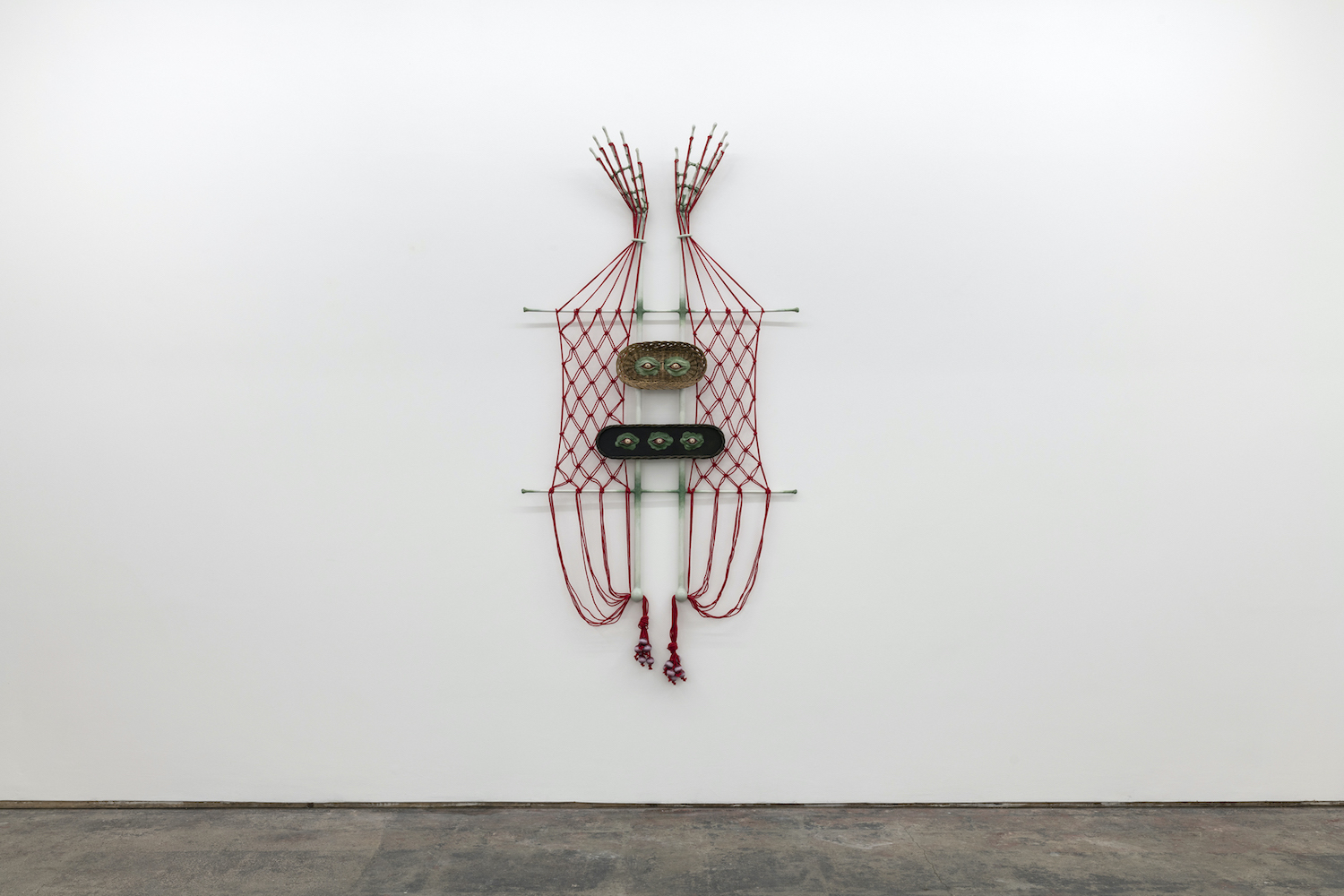

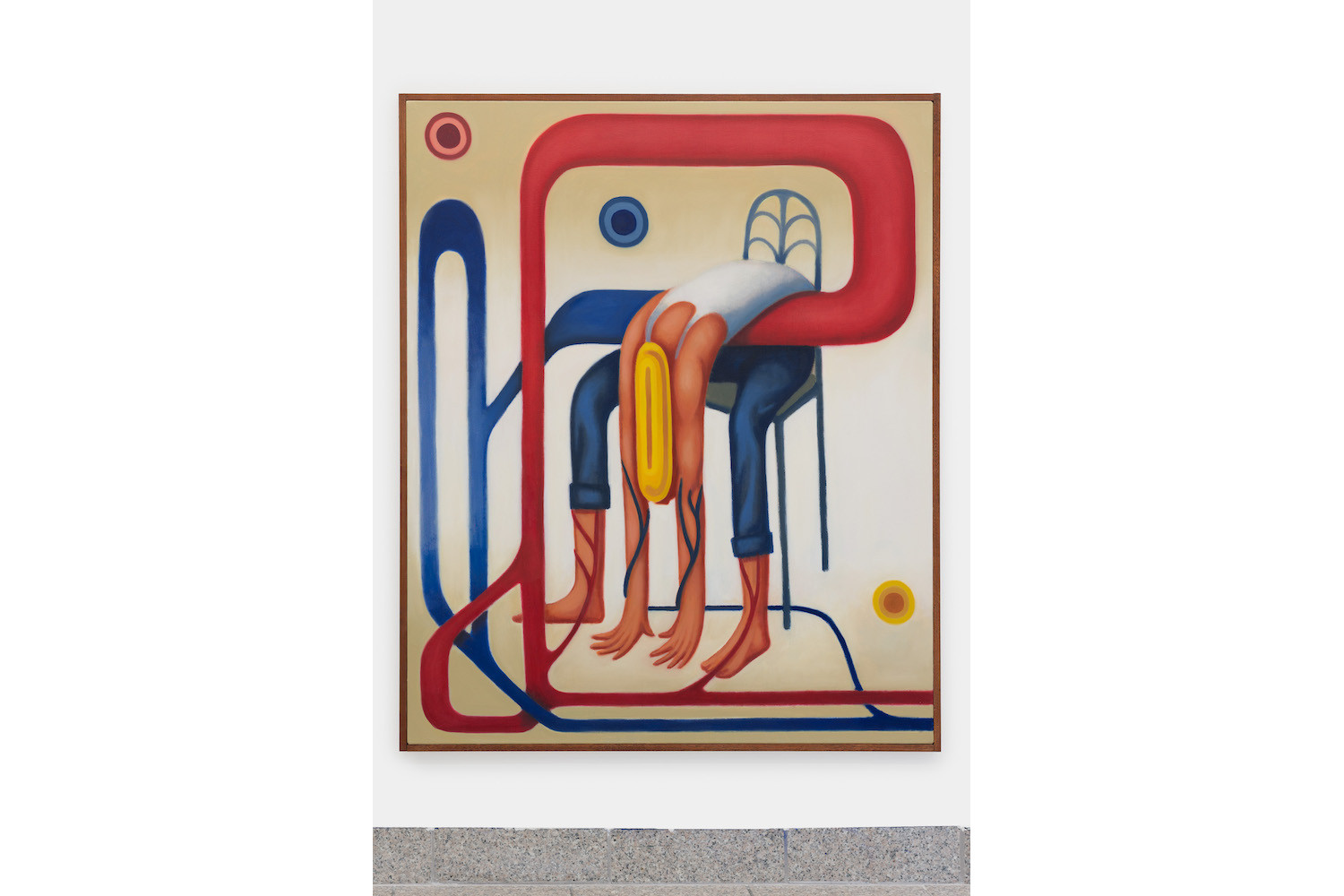

That ornament and embodiment become sinuous systems demonstrates Fitzpatrick’s continued interest in an inexhaustible premise of incorporation. The idea of incorporation depends upon the absolute division of inside and outside, but in the act itself that opposition vanishes, dissolving the structure it appears to produce. Indeed, Fitzpatrick’s paintings and sculptures entwine body, building, and symbol as hydraulic matrixes often beholden to absorption, infection, assimilation, or subordination, liquefying their structures of meaning as they enlace. In Fitzpatrick’s painting, this is often evoked in the metaphoric, the device that exposes resemblance and relationality as it disintegrates category. Here, one returns to the diagrammatic composition in Fitzpatrick’s manipulation and transcendence of borders. While each painting resembles something legible, evidence of the metaphor at work, there lays a wellspring of sensibility — the incorporated bodies, motifs, and objects offer meaning in the same instant that the very mechanics of their meaning are dismantled.

The act of incorporation implies the prospect of metaphorically beneficial contamination as much as it does the possibility of annihilation of the imbibed. More than anything, Fitzpatrick reinforces his queer world-building and rewriting of history at the level of style — principally incorporating ornament with a dose of fantasy, considering the covert expressions of a given stylistic influence if tinctured by imagination. For instance, Fitzpatrick has spoken of his interest in the medieval manuscripts of the Book of Kells, whose interpenetrative drawings of human and animal life with typographic form led him to imagine romantic liaisons between the monks working in isolated monasteries. Other historical references — pagan culture, Celtic knots, sigils, art nouveau design — are applied for libidinal subtext, which trace the influence of a pre-modern mode of expression in excess where symbolism meets embodiment. Consider Self-Digestion Sigil (2017), in which two builders, captive in the belly of a swan, suggest the metabolic, absorptive, and alienating capacity of representation when addressing sexuality or identity. Elsewhere, an art nouveau couple, pure musculature and curlicue, merge with the table and meet one another in a kiss — an infectious mirroring. Fitzpatrick’s style lubricates his tone so it may ripple with erotic frisson, comical joy, or suspicious distance.

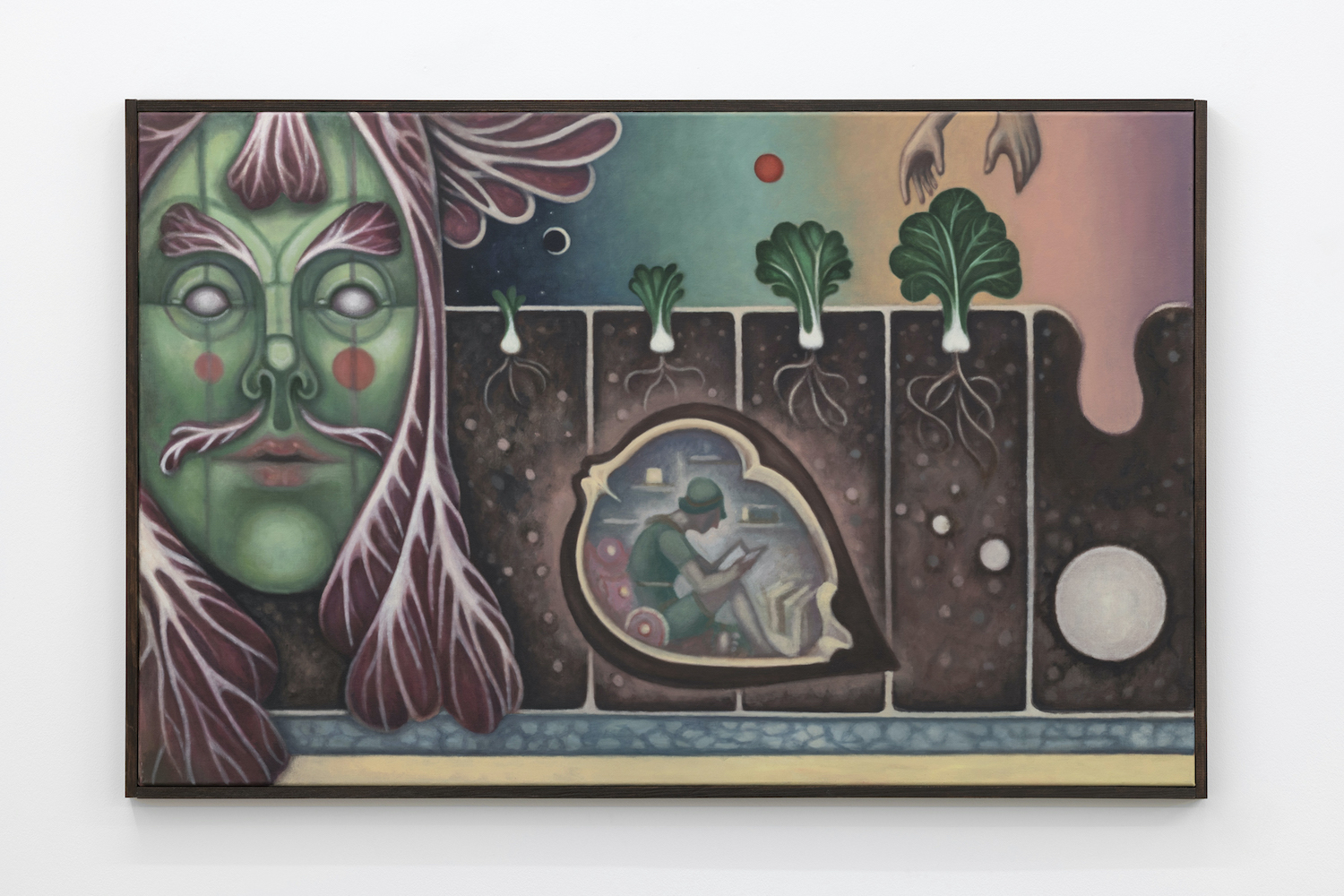

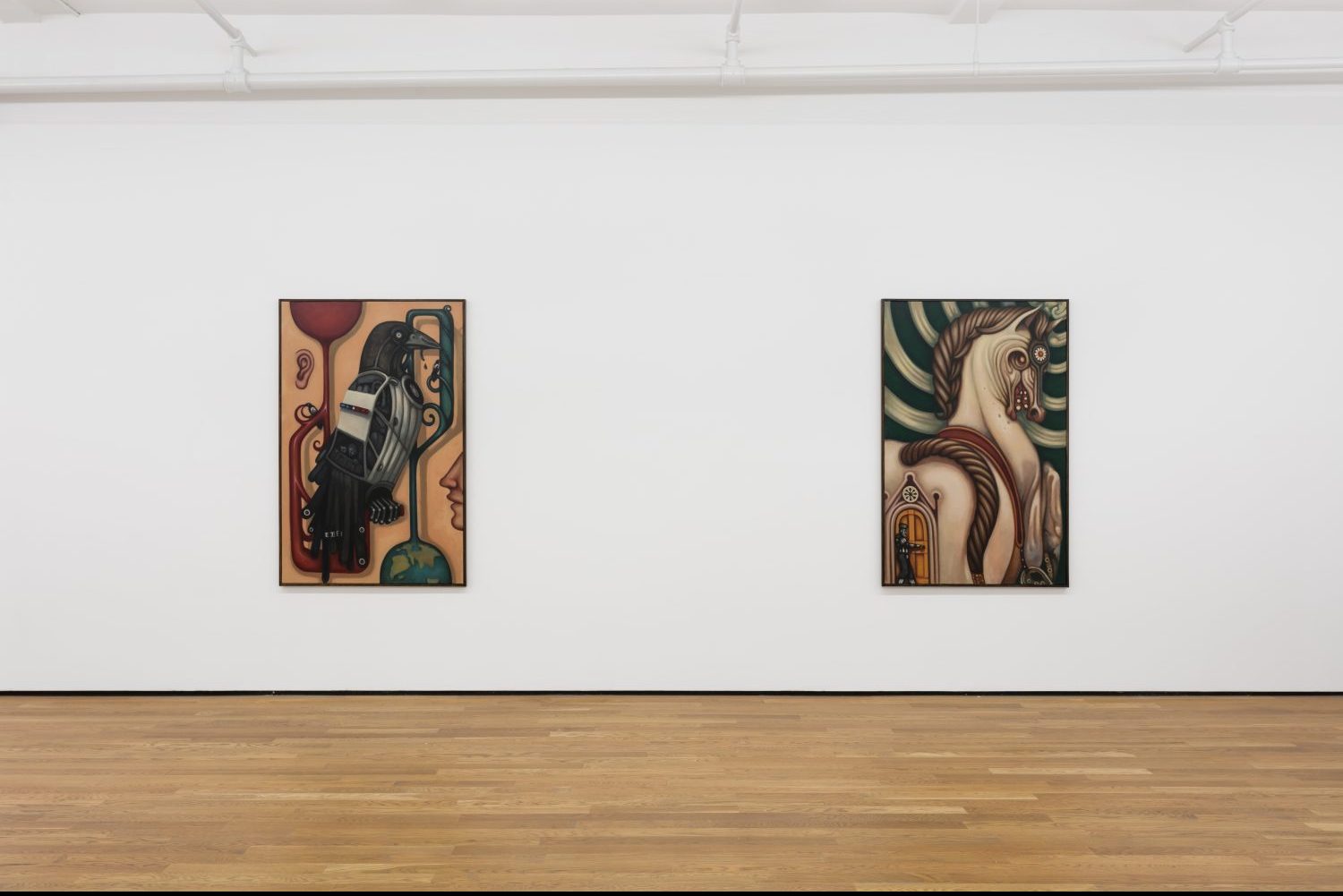

For his recent exhibition “Omega Salad” (2020) at Seventeen, London, Fitzpatrick identifies taste as a theater of compositional pleasure, a blueprint for cultivated behavior as well as the very process of incorporation. In the exhibition’s titular work, touch, pampered by white-gloves, serves the plated centerpiece: anthropomorphic lobster coupledom haloed by irradiated cabbage leaf, their boiled armor sporting cute cutaways exposing risqué tomalley. Tuxedoed and sylphlike: a deco latticework of waiters are interlinked and electric with pulmonic charge, glinting, flushed. Omega Salad (2020) is somewhat neurotic. Teasingly, it articulates haute cuisine as hierarchy in action as well as a fleshly system stirring with somatic impulse.

It is presupposed that the inside appears as superior to the outside, the periphery protects the core, but Fitzpatrick locates the metaphoric potential of incorporation as fundamental transformation, agitating the illusory sovereignty of the center from within. Omega Salad displays the dramatic surface of gastronomic performance as one that is continually compromised by the body, magnifying the lobster as an agent of decadent pleasure and disintegration. Fitzpatrick’s lobster reminds one of the techniques used in metaphysical conceit poetry, which loads the metaphor so far it becomes meaningful only through sheer imaginative leaps. The lobster is the viewer’s bait, which parodies the stifled libidinal wish and whose decadence in taste Fitzpatrick connects to the implicit indulgence of Catholicism’s rite of communion. As he writes in the exhibition text: “This diagram of mutualistic digestion and relational transformation feels both sensuous and positively pagan. Under the moralistic surface lies an obsession with terminal ecstasy, an orgasmic extinction of self.”

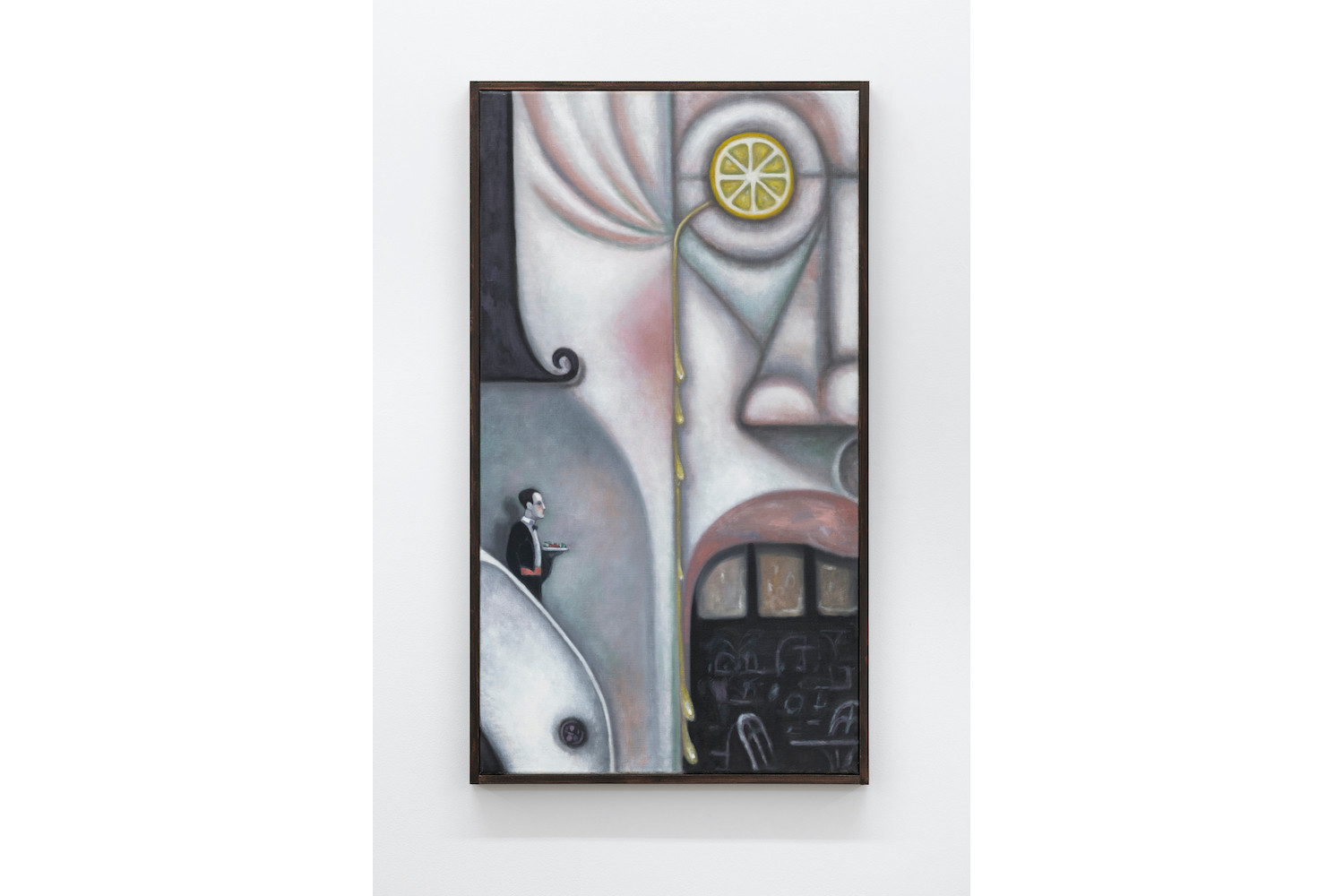

The tension of the straitlaced surface and the libidinal underbelly is worked over in Fitzpatrick’s canvas, where at times the relations of incorporation or dependence hijack the chance of illuminated transformation. A Conflict of Interests (2020) is a somnolent, reddening, promethean-cum-deco portrait. Gliding buttery folds of hair are flame-fat-flesh cut through like cured meat to reveal hemoglobin-red viscera. Standing adjacent is a dinky, parasitical, berobed monk who could be healing the host’s cochlea or wiring the nervous system itself. Meanwhile Chef’s Table: France (2020) depicts the cadaver of a 1920s tuxedoed waiter as hollowed-out architecture, his gaping mouth a doorway, his curved shoulder a romantic dining cloister, his engorged sallow cock the chef’s table, and his reinforced haunch finished at the tail end with a cigarette’s marshmallowy pouf of smoke.

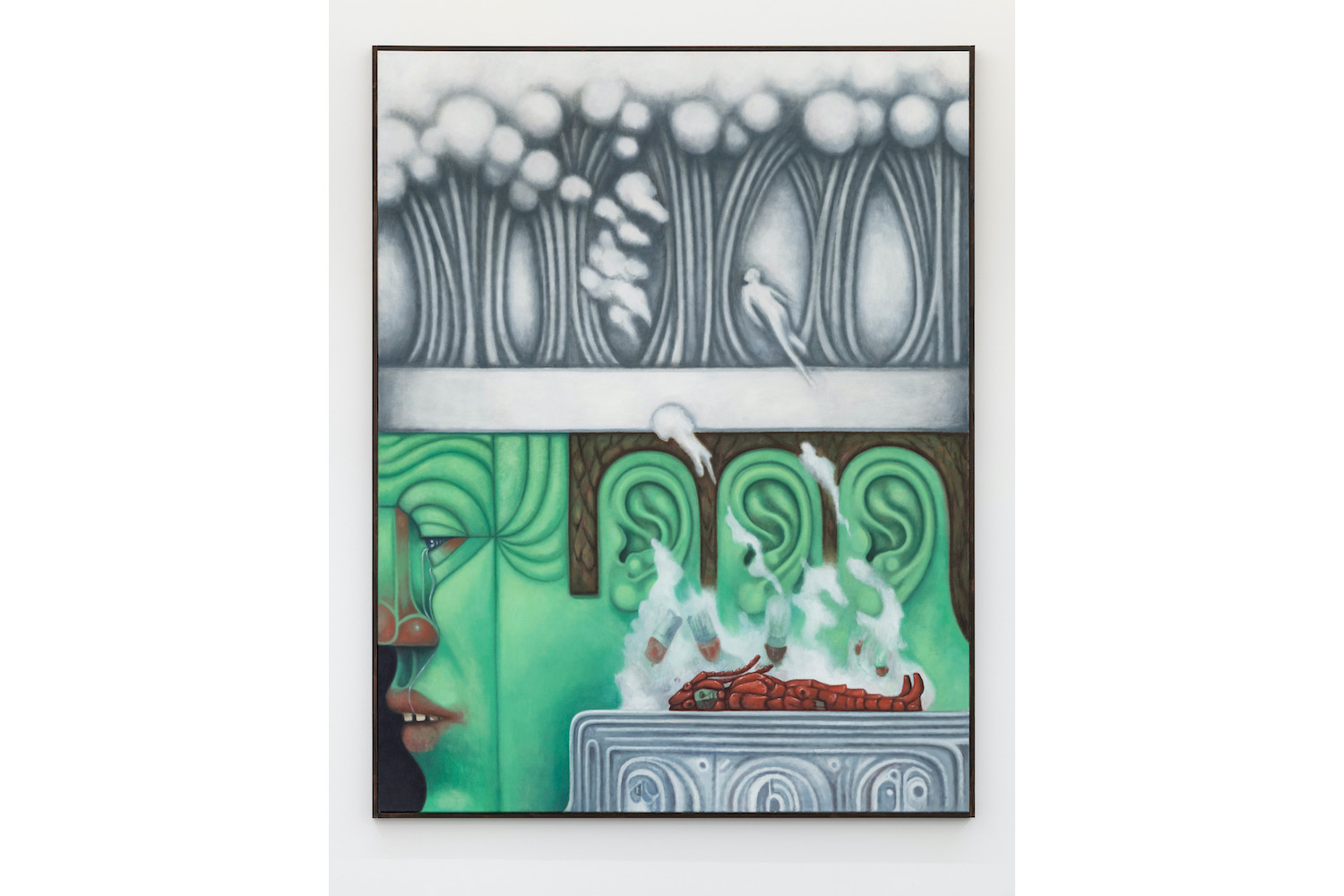

In Psychopomp (2020), the suggestion of transference, evaporation, and disembodiment is more magically charged. In the divided painting, the lower half depicts the anthropomorphic lobster atop a stone table, its backdrop a monolithic face of Frankenstein green. The profile’s furrows roil with art nouveau decorum; his sequential trio of ears like monastery archways compel a kind of echo, while his waterlogged eyeball streams like a maudlin fountain. The lobster’s steam initially models the chef’s at work yet continues to evaporate into figural wisps that travel to the upper realm of the painting, a woodland of cambric white fluff. The lobster’s now-immaterial ontology is fantasized but given osmotic process, which, as Fitzpatrick writes, “might resemble a journey into the afterlife.”

In Fitzpatrick’s work, one sees a frequent derangement of polished systems, made leaky and irrepressible to not only quash the concept of the body as inviolable but to probe the constitution of the capitalist subject and the machinery of categorization. For the center/periphery image clearly evokes the capitalist logics of assimilation and gentrification. Oftentimes, he recalls the manipulation of the body as a model for social structure, which, abstracted and individuated by church and state, subsequently estranges the very body from the self. In Fitzpatrick’s use of symbolism and metaphor, the body is foregrounded or reinserted to release these puritan practices and systems of their much-needed sensorial milking, in turn ushering latent queer readings to the surface.

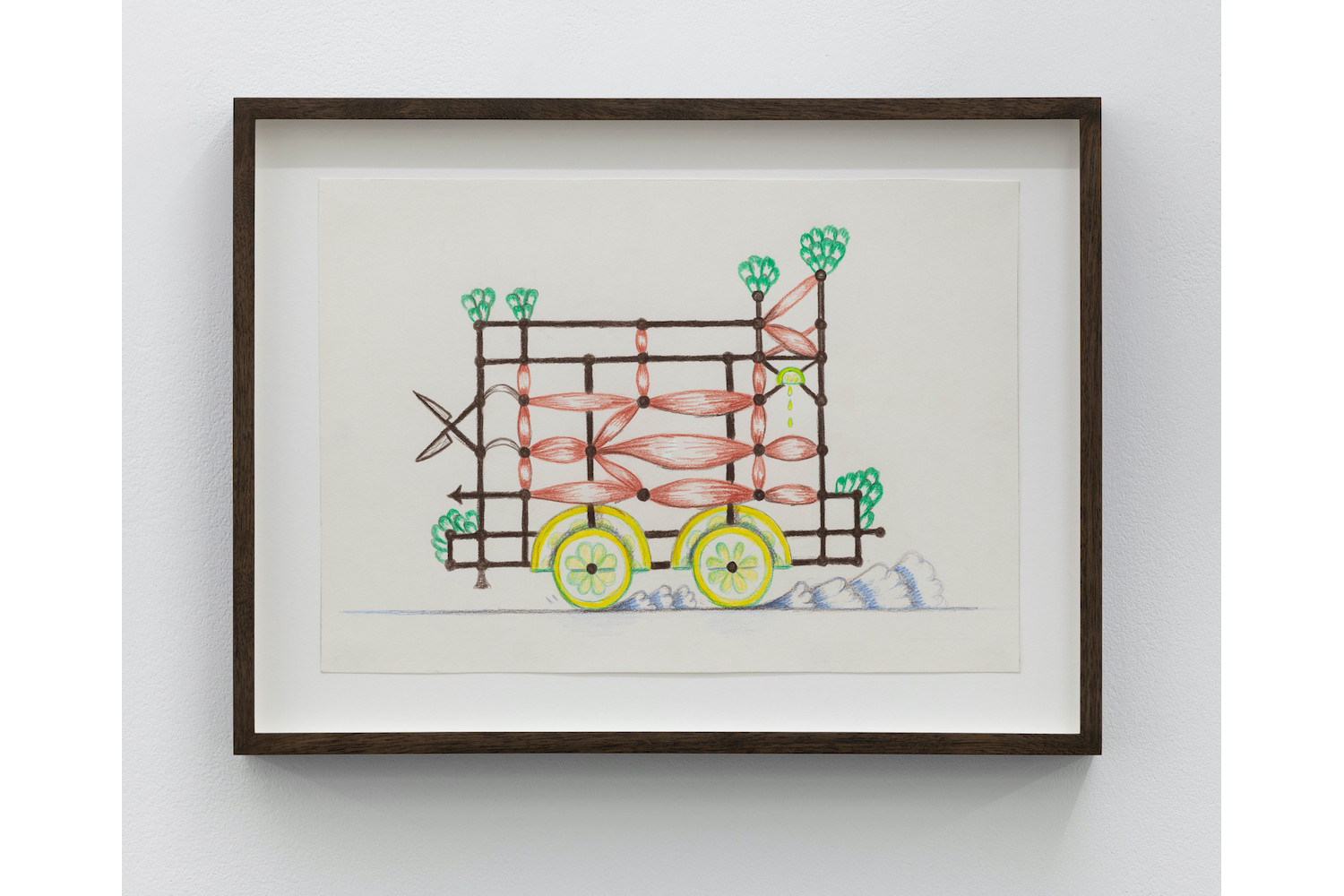

For the exhibition “Uranus” (2017) at Sultana, Paris, Fitzpatrick referenced Arthur Evans’s Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture (1978). Evans argues a documented gay history proper must include mythology and invention, for “all historical works are one-sided, subjective, and arbitrary.” Entwining Evans’s argument that aligns the persecution of witches with homosexuality alongside fears around infection during the AIDS crisis, Fitzpatrick deploys the metaphoric potential of infection as a “countermovement” that contaminates history from a gay present. Uranian Monks (2017) positions two Franciscan monks mirroring each other in reverse like a playing card. The figures, enclosed by brickwork, are conjoined at the groin by a glowing, double-ended phallus, their pressing embrace recalling the ornate initials of medieval manuscripts. In others, a hare and cat are infected with daisies — their tendril stems drawing a calligraphic f or s. Town planners (Demi-Urges) (2017) showcases a builder — back turned, legs spread, and muscles ripped — bookended by two others, somewhat in service but all in acknowledgement to the member between his legs: a daisy. Fitzpatrick’s sexualized builder is a recurring motif that articulates the slippery influence of gay assimilation, in which incorporated sexuality devolves into another consumer base and inspires a renewed propulsion of gentrification. Take Trickle Down Theory (2017), in which the builder has clocked out. His verdant, money-colored vest is slack about his chest, baring his nipple. With jeans undone he strikes a light for his smoke while behind him freshly erected coral pink rooftops appear like industrial massifs. But what curves into his bicep, slopes down his pectoral and tucks into his waistband? A currency symbol: £.

Fitzpatrick’s reference to historical, pagan eras responds to what sexuality and the body has lost in the present, while the allusion to industrial nineteenth-century inventions of sexuality address our toxic contemporary inheritance. That these temporalities may exist on the same surface allows a set of existing tensions to unevenly coalesce: liberation, assimilation, sensuality, productivity. Yet Fitzpatrick’s reaction to historical narratives of condition, persecution, and repression are made generative in his spells of absurdity and comic indulgence. For instance, Underworld (2019) at Kevin Space, Vienna, references Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of the grotesque — the idea that the medieval social body was once a porous entity where sex, defecation, feasting, and urination occurred in public. In its antithesis, St. Thomas Aquinas, the philosopher who created a taxonomy of sexual sins, is repurposed in a set of three spindly sculptures seen diligently cleaning up small white beads, identified in the press release as “spilled seed of Coitus Interruptus, Self Love, and Sodomy.” These noodley wooden armatures are studded with accusatory fingers and squirming faces, their pretzeled tendons wedded to spades, brooms, and brushes to attend to that naughty, naughty spate of spunk.

The immersion of polymorphic symbolism lets Fitzpatrick’s relations and divergent registers literally convolve, but there is a kind of warmth when his address is more specific. As part of “A Pulsation of the Artery” (2019) at Foxy Production, New York, Fitzpatrick created three sculptural odes to William Blake, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and Walt Whitman. Translating a section of Blake’s Milton — in which Milton enters Blake’s foot — sandaled feet and bare leg bones harbor twiggy veins, flowers, and white glasses. Sedgwick’s essay “White Glasses” (1993) was initially written as an obituary to Michael Lynch, a friend suffering from AIDs, but soon involved her diagnosis of breast cancer during the time of writing. The essay became an attempt to sustain both writer and friend, such that Lynch’s own identification as a gay man, noted by his white glasses, is melancholically incorporated to function as a beneficial yet temporary resistance against death in writing Lynch’s illness through her own. Fitzpatrick’s allusion to “White Glasses” gestures to the broader scope of his work, how metonymic incorporation, metaphoric drift, and queer enrichment might encourage a more florid and fluent worldview, loosening selfhood in its swirl.