Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

“I want a dance where a body moves as part of its environment,” wrote Carolee Schneemann in 1970, “where the dancer says Yes to environment, incorporating it, or says No, transforming it.”

The year 2020 has required both incorporation and transformation as each body on the planet has adapted to the regulations of a strange new environment. As the performance world tiptoes on the ever-slackening rope of the pandemic, artists and curators have been forced to rethink how we “do” performance: rejecting or reassessing certain prescribed modes and values; adopting and returning to others. While the enforced pause in production and hyperactivity came as a welcome reprieve for many, the subsequent drop in income and support for artists working across dance and performance has revealed an inherent flaw in how the art world functions. Video work and online encounters have become central conduits for the live experience. Within this, several artists have been interrogating the past to pose the question: Where do we go from here?

Since sharing “an evolving love/break-up letter addressed to contemporary dance” in 2017, SERAFINE1369 (Jamila Johnson-Small, previously Last Yearz Interesting Negro) says, “I don’t want to get stuck talking about things that are not about movement and transformation. […] I don’t really concern myself with ‘contemporary dance’ or not contemporary dance, the system, the histories, the languages. […] I really feel it was a break up letter, a clearing space.” For SERAFINE1369, the past eight months have been the longest period without traveling or performing in about a decade. They have since been making work for/with graduating dance students that use an online game format, as well as sharing works remotely. At My Wild Flag Festival this year in Stockholm, I Have Become A Prayer was a remote dance presented as an installation “with sound, projections, and a lot of lavender” within which live audience members were invited via notes laid out in the space to perform different actions that became part of the choreography. There is a sense of collective and personal reconstruction within SERAFINE1369’s practice. “In many ways we are always adapting, moving in relation to shifting circumstances. I think the impact or the way that this time, these changes and regulations, will inform who we are and how we work and also what kind of work gets made will take time to manifest. In many ways, I am still in shock, processing.”

SERAFINE1369 is currently leading a six-week online sharing of thoughts, strategies, and questions that inform their choreographic practice. Hosted by Siobhan Davies Studios, the course, titled “Oracular Practice,” is informed by research into movement and dance “as a tool for divination, decoding messages from an oracular body — on personal/structural/symptomatic/somatic/psychic levels — to be processed through the medium of choreography.” The workshops invite participants to incorporate “the situation of online encounters to support deeper engagement with your own environment (internal and external and virtual).” Using technology as a medium for choreographic understanding, SERAFINE1369’s approach explores how a remote connection can be recalibrated as a tool for manifestation. Content that emerges from participants is considered “as oracles, imaginative guides, sites that encourage unanticipated relationships to meaning, through listening, reading, and shifting orientations.”

In a similar vein to SERAFINE1369’s “love/break-up letter” addressed to contemporary dance, Paul Maheke published an open letter this spring titled “The year I stopped making art. Why the art world should assist artists beyond representation; in solidarity.” Maheke’s letter highlights historic cycles of racial and socioeconomic prejudice layered within and around the context of the current crisis, underlining how many artists do not have “a safety net or support structure” to fall back on. Loaded comparisons remind us how Black artists have historically had to work with and against social and environmental limitations and how the infrastructure of the art world is built upon this deep fissure. In Maheke’s 2019 work Sènsa, made with Melika Ngombe Kolongo [aka Nkisi] and Ariel Efraim Ashbel, the artists’ proximity to the live audience was fundamental. “I received invitations to participate in online shows but declined,” said Maheke in a recent interview with Frieze, “because I felt that most of the proposals failed to address what the context demanded: a complete reset of the art world’s material conditions. COVID-19 has shown us how dysfunctional the system is.”

Dancer and artist Zinzi Minott’s short film Fi Dem III premiered this autumn at the Berwick Film and Media Festival. The film is part of the ongoing series “Fi Dem,” which began in 2018 as “a commitment to the Windrush generation, and a continued investigation of Blackness, diaspora, and the heritage of her family.” Invoking her ancestors, her steps forward as an artist and dancer carry the weight of the past into the present. “My ancestors meddle, they interfere, they see cracks and break through and they scream with us, they rage with us, they remind us,” writes Minott in her accompanying essay “Ancestral Interference.” Minott’s words are reminiscent of Schneemann writing in 1970: “I want a dance where dancers can fall, can crash into a wall; aim movement beyond their line of spine INTO space, into materials, into each other — projective, connective!”.

“Pour out and walk,” writes Minott. “That scream stuck deep down in your throat is not yours alone. […] Everyday I get closer to becoming an ancestor. I will interfere. There will be meddling, there will be interference. I will interfere.” There is a sense of conjuring in Minott’s work, raising the voices of the past. With the impact of the pandemic, the current groundswell of activism and action against injustice, this year has called for a seismic shift, an upturning of common grounds that resonates within Minott’s work.

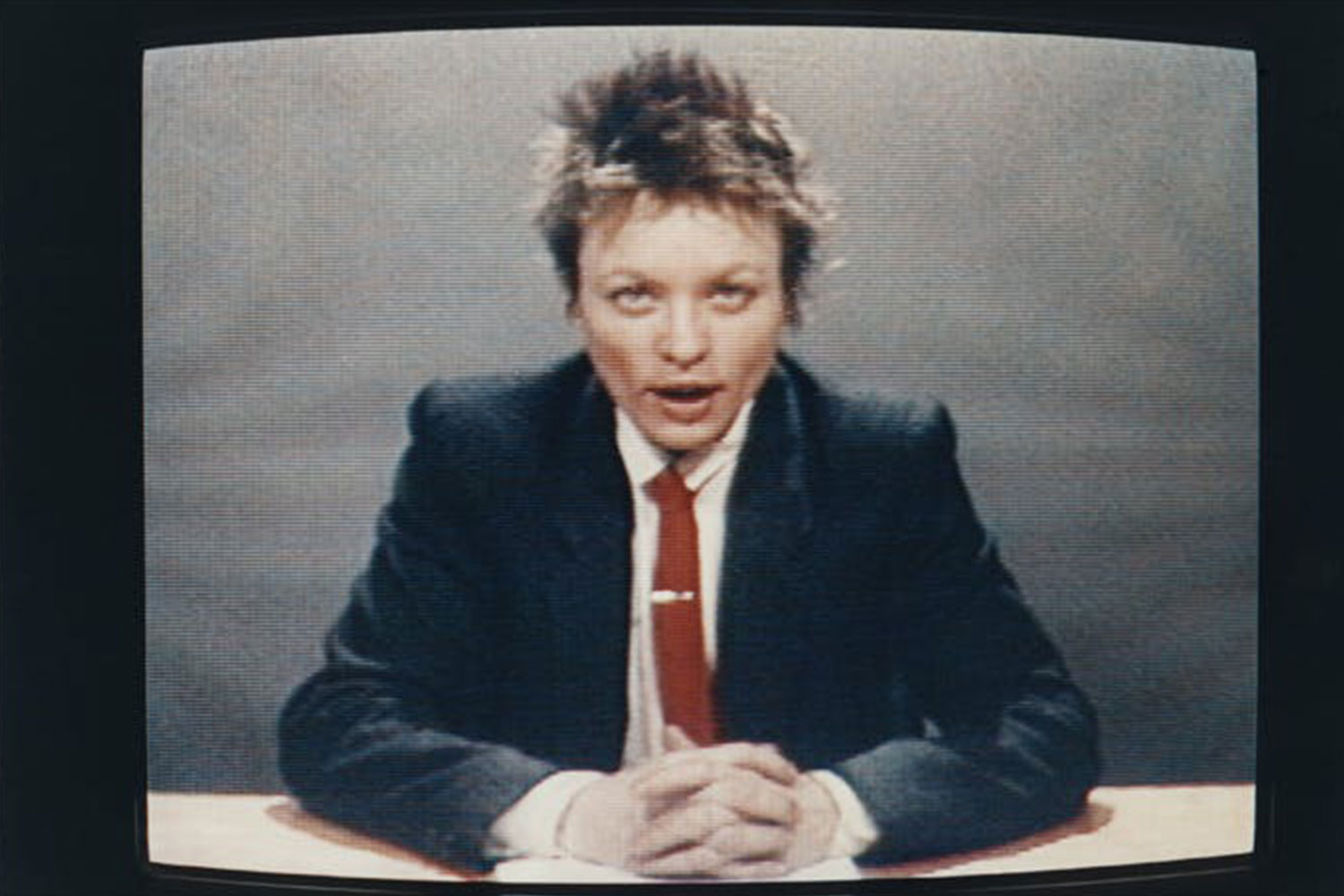

As new limitations offer new discourses surrounding movement practices, curators and performance-based organizations are likewise working with and against such limitations. In response to the pandemic, Performa recently announced their Performa Telethon fundraiser celebrating the organization’s fifteen-year anniversary. The eight-hour live broadcast from Pace Gallery in New York on November 18, 2020, will include glimpses of Performa’s fifteen-year history with rare footage from the archives including work by Joseph Beuys, Merce Cunningham, Yvonne Rainer, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Glass. Artist editions and homewares will be sold via a QVC-style “home shopping” segment. Inspired by Nam June Paik’s iconic 1984 live broadcast Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, the global telethon will help raise funds that directly support the artists, musicians, dancers, designers, producers, and crew of the Performa 21 Biennial scheduled for 2021. The telethon itself will be free to watch for viewers around the world.

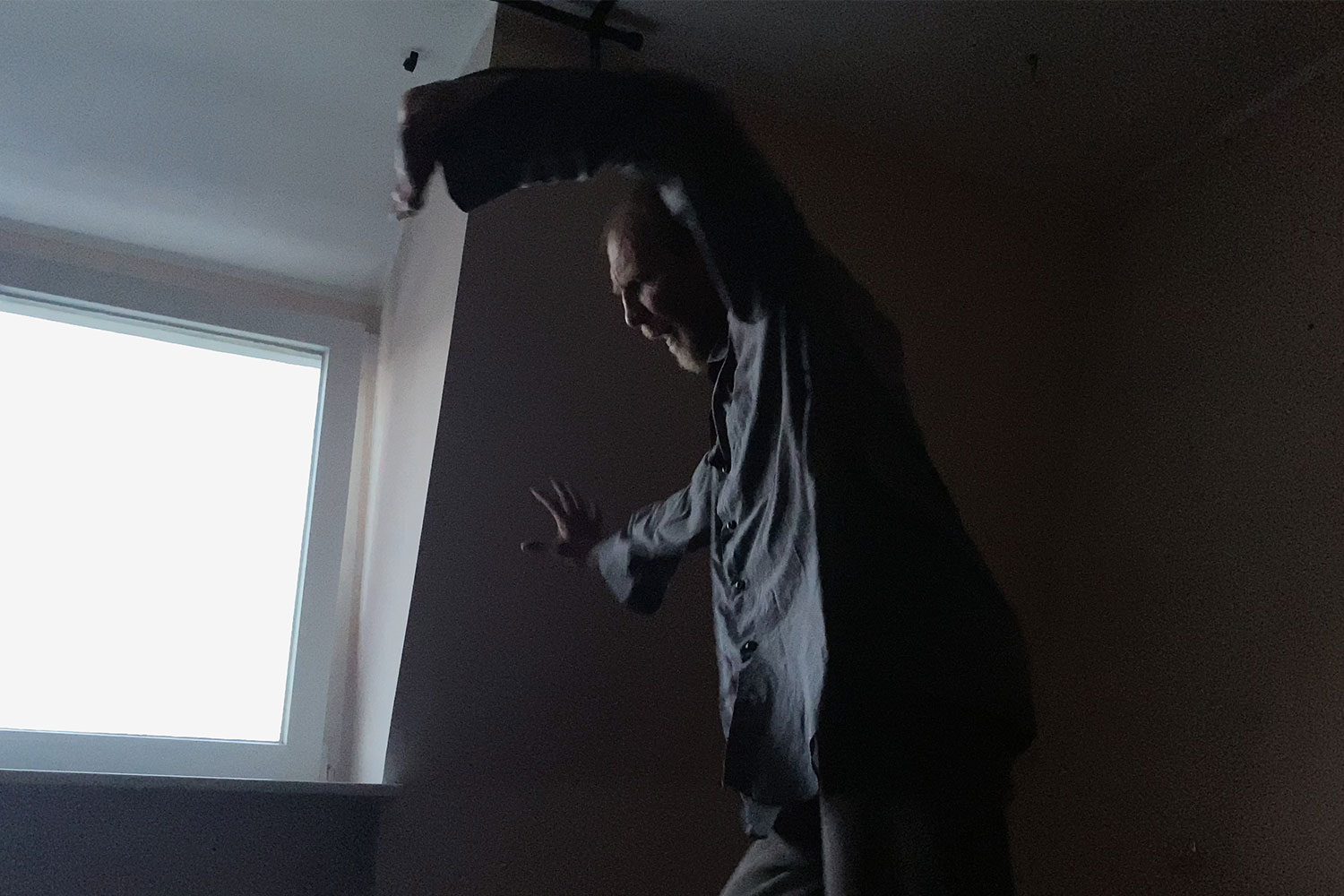

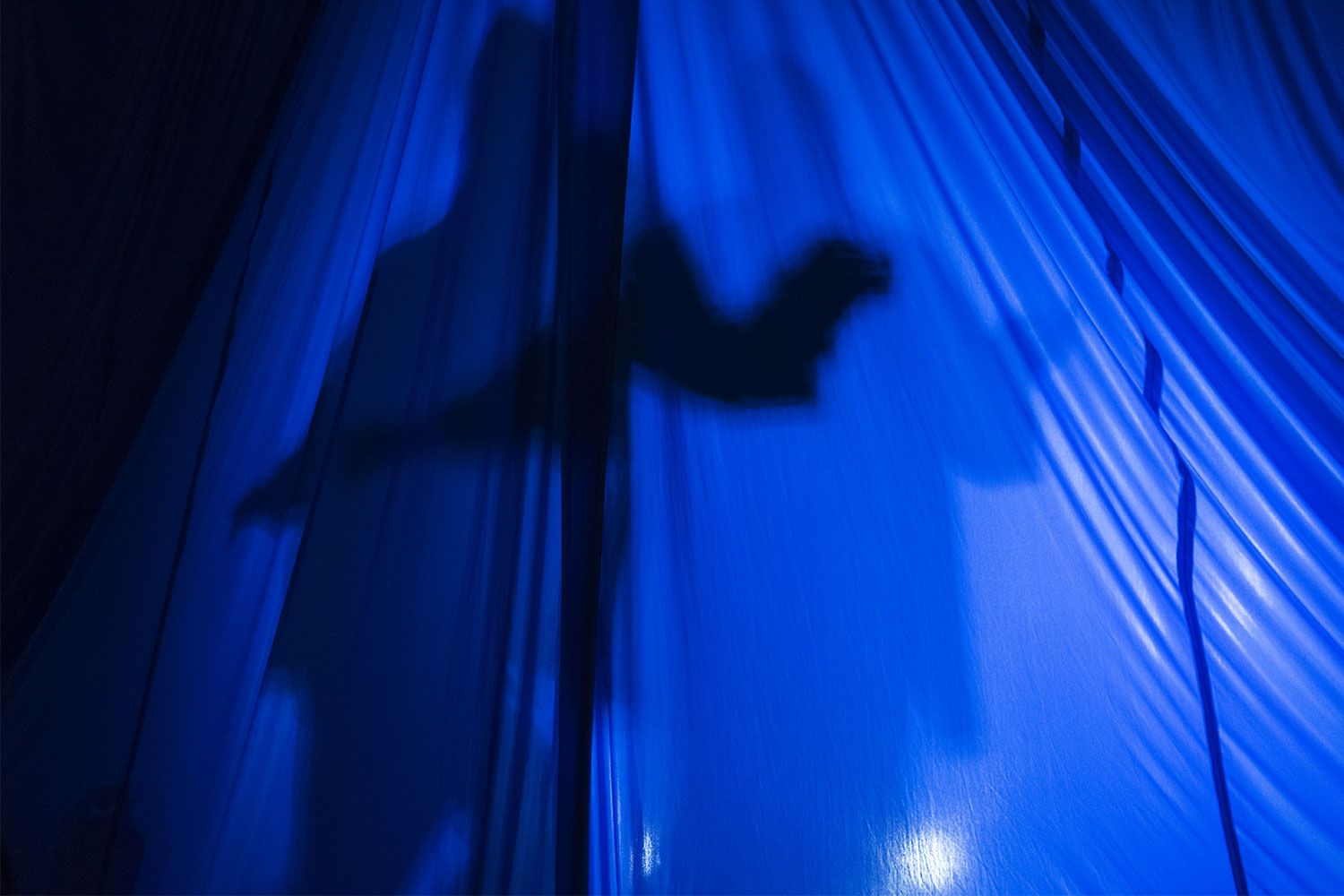

“Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer” opened at the Barbican Centre in London this month, the first major exhibition of the dancer and choreographer’s work. Video work from the 1980s to recent years is showcased across the main space, interchanging between double-sided screens mounted overhead and several monitors at eye level. Careful curation has allowed space for intuitive distancing. As masked visitors move tentatively around the large overhead screens, their movements create a kind of incidental choreography beneath dancing images of Clark’s punk ballet aesthetic. Each screen takes its turn to be subtitled or turned on full volume, inviting visitors to follow the ear or the eye as audio bounces from one floating scene to another. Elvis’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight” features on the soundtrack of one of Clark’s video works, playing sporadically throughout the exhibition, which also features works by Sarah Lucas, Leigh Bowery, Charles Atlas, The Fall, Wolfgang Tillmans, Cerith Wyn Evans, Peter Doig, Silke Otto-Knapp, Duncan Campbell, and others. Combining ballet technique and punk culture, Clark’s work spoke to a time of loud resistance in the 1980s and ’90s, voicing an unapologetic value system that still speaks volumes in protest-driven 2020.

This year has revealed some problematic attitudes surrounding performance practices, particularly highlighting the way performance artists are often treated as pay-per-view consumer items, one-night wonders. The pandemic has forced artists and curators to question what the future of live performance will be. Though it may be too early to expect a clear response, these early utterances mark the first steps toward divining and redefining future movements.