Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

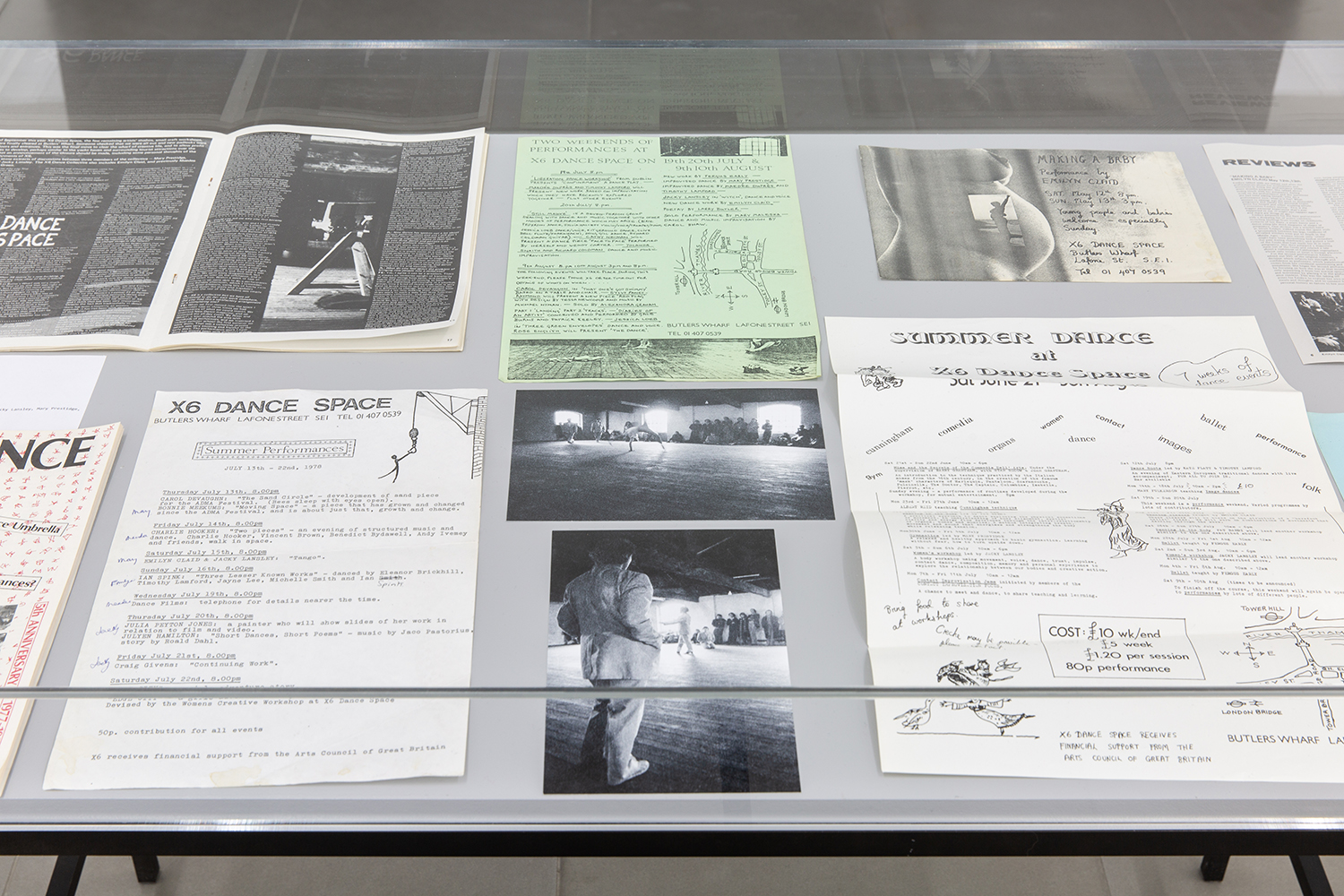

“X6 Dance Space (1976–80): Liberation Notes” at London’s Cell Project Space is the first presentation of work from the X6 Collective, a countercultural dance movement that was active in Britain between 1976 and 1980, founded by Emilyn Claid, Maedée Duprès, Fergus Early, Jacky Lansley, and Mary Prestidge. Occupying a disused tea warehouse in Butler’s Wharf, on the south bank of the River Thames, the group initiated a collaborative and supportive environment — the X6 Dance Space — to teach, share, and perform experimental new work that stood in resistance to the work being produced by mainstream companies and institutions. When they were evicted in 1980 due to the building’s redevelopment, they lifted and removed the old maple floorboards, grafting them into their new space at the derelict varnish factory Chisenhale Works in Bow, which later became Chisenhale Dance Space.

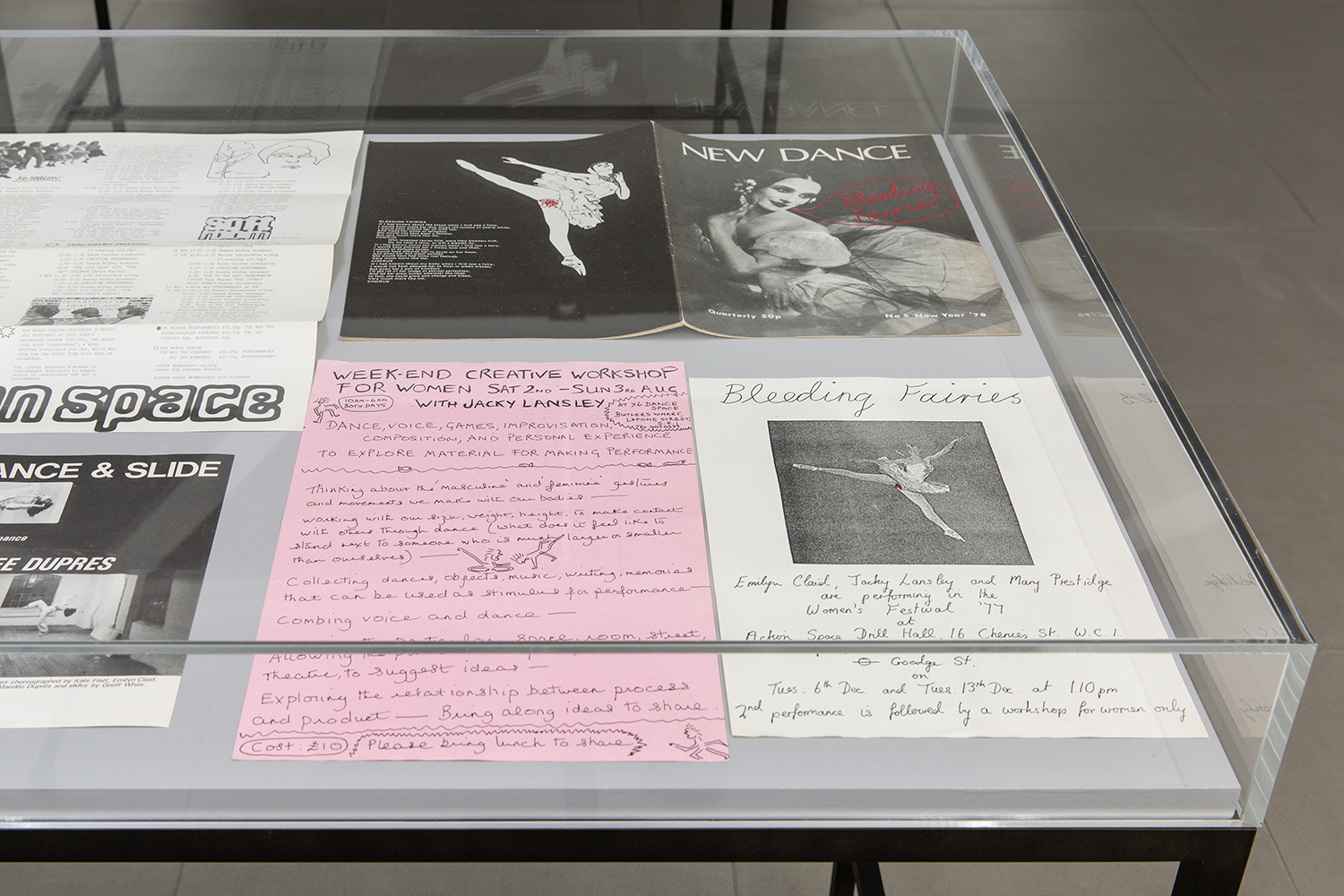

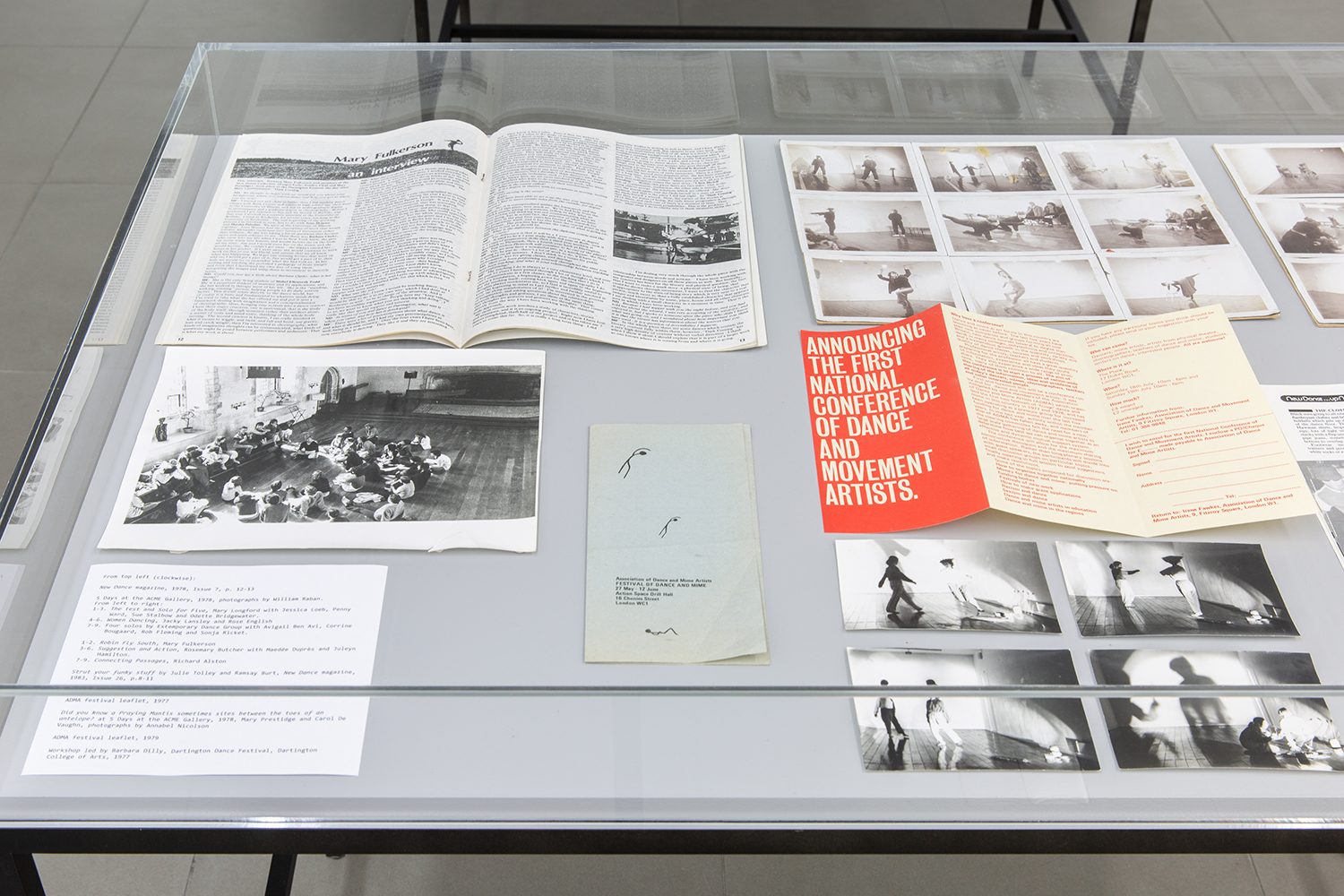

The radical “new dance” movement in Britain — a riposte to conservative cultural practices fuelled by the shifting social politics of the time — developed from the early classes, performances, and writing of the X6. The group was also connected with Dartington College of Arts, where they mixed with international avant-garde practitioners such as Mary Fulkerson (who organized the Dartington International Dance Festival from 1977–78) and Steve Paxton. “The X6 were concerned with a new approach to dance aesthetics, organization, and teaching, informed by emerging feminist and queer theoretical frameworks,” writes the show’s curator Rachael Davies, who was interested in “the opportunity to reconsider the legacy of X6 within a contemporary framework.” The exhibition is an archival display, comprised of original photography and footage from performances and rehearsals, in addition to vitrines holding publicity ephemera and a selection of texts. The public program has featured performances from members of the X6, in addition to a new commission from contemporary artists Sanna Helena Berger and Shade Théret, and a roundtable discussion on the social and political parallels between the 1970s and today.

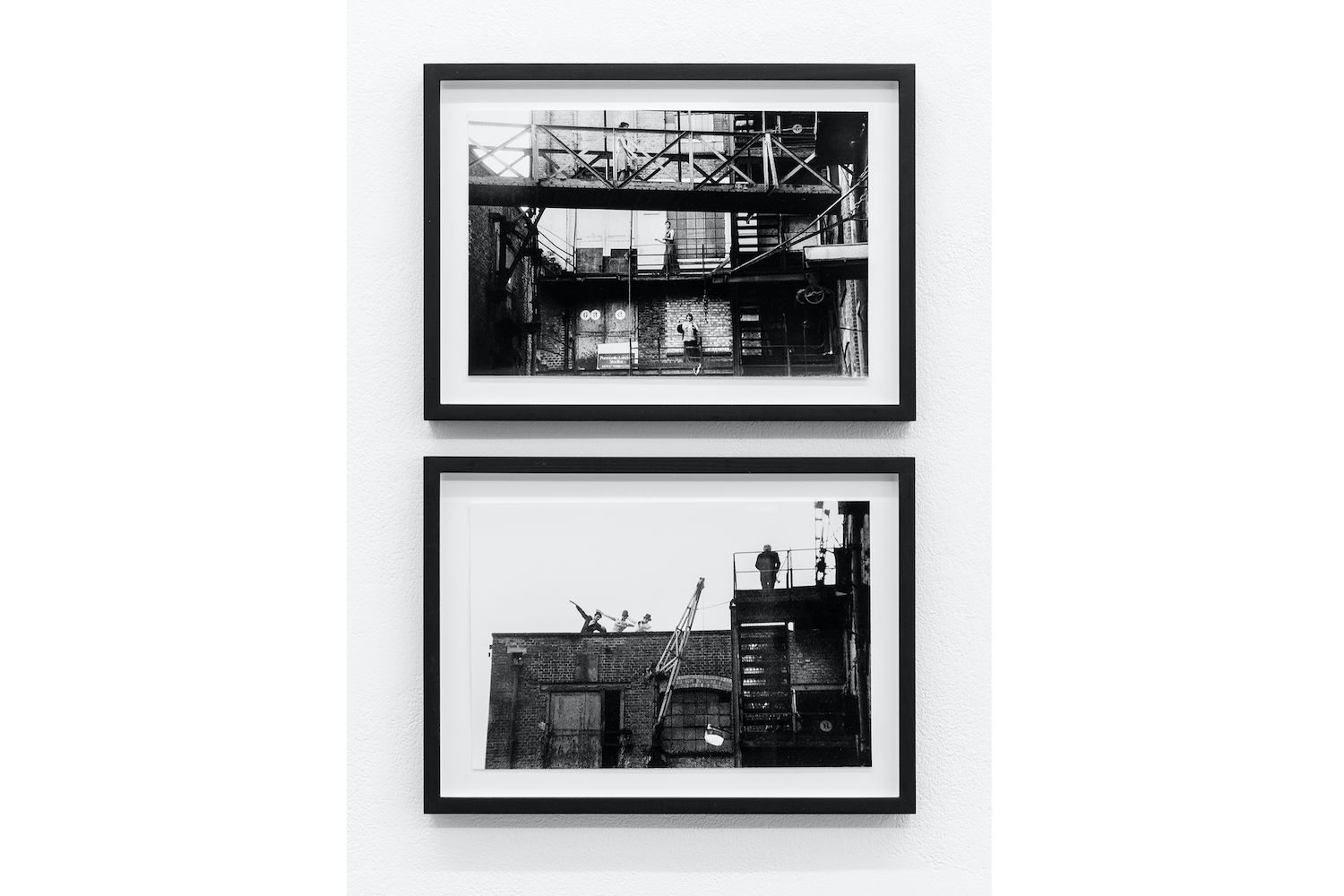

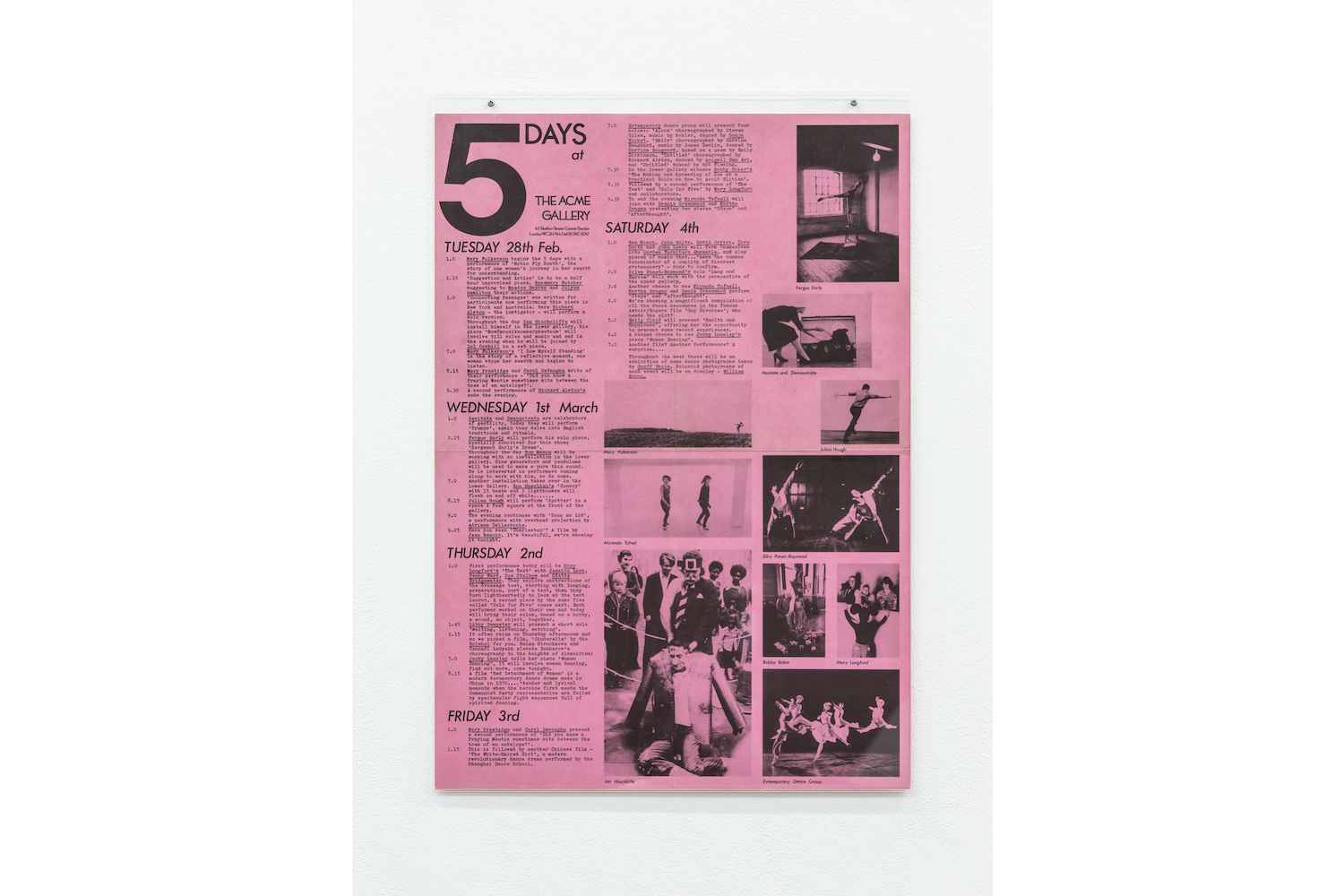

As an important yet underrepresented moment in British cultural history, the work of the X6 is particularly prescient with regard to an accelerated interest in interdisciplinary practices and the related programming of dance and performance within art institutions today. Part of a wider network that included the London Musicians Collective and the London Filmmakers Co-op, the X6 collaborated with artists involved in theater, film, and music, in addition to those working with visual and live art. The 1976 performance By River and Wharf, recorded through a sequence of photographs by Geoff White, is indicative of their pioneering approach. The collective organized an afternoon-long festival of performances that took place throughout the Bermondsey docklands, with various members of the collective creating original performances for specific sites. Spectators were led by tour guides from Tower Hill over Tower Bridge, around Butler’s Wharf, on the banks of the river, down alleys, old bomb sites, and on the grounds of housing estates.

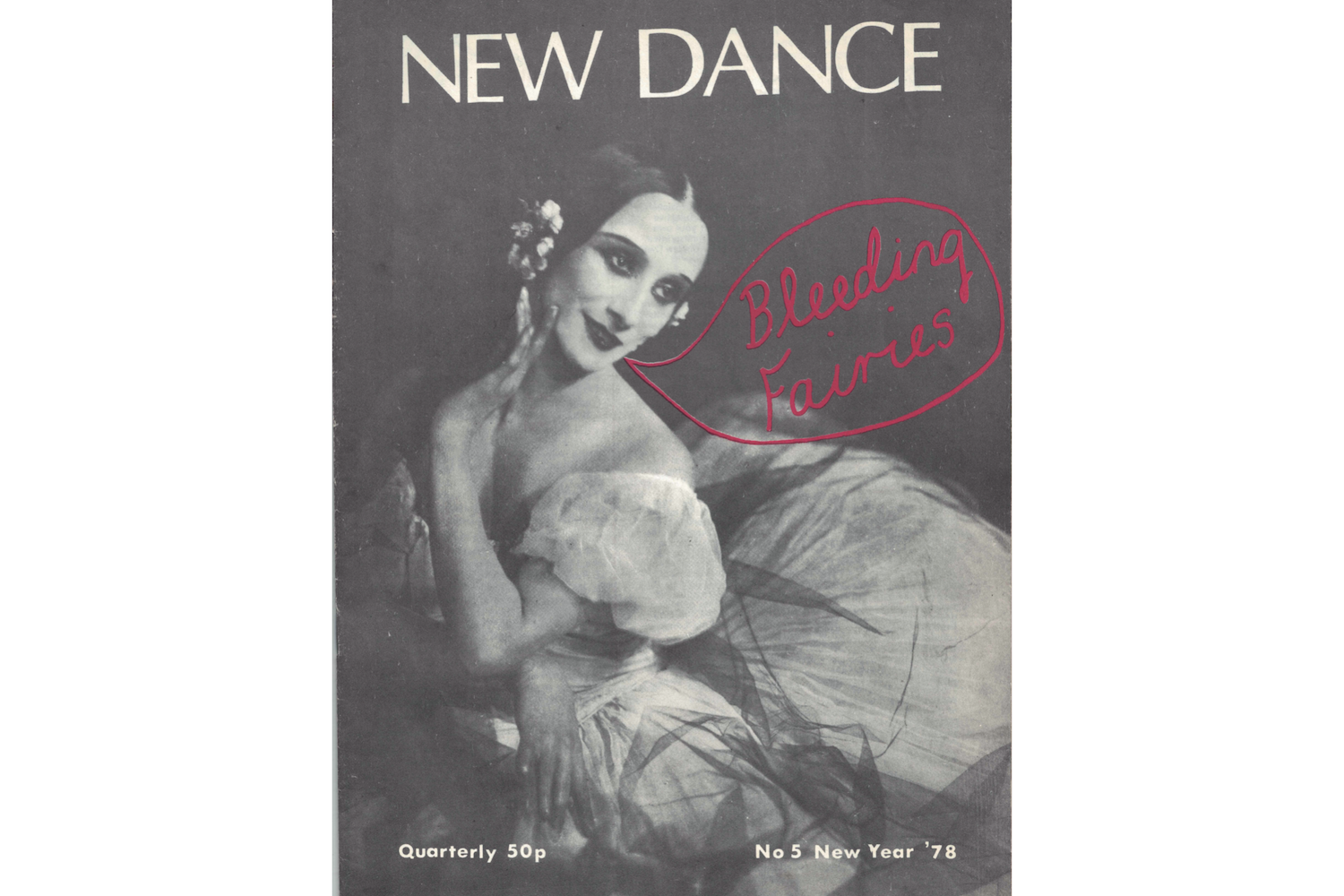

The X6 Dance Space was peer-led, producing a program of performances, classes, discussions, and workshops. This sense of cooperation also led to the creation of New Dance magazine, which ran from 1977–88, with each issue being edited by a different collective. Initiated due to the lack of critical writing on dance, the pages created a necessary editorial space for choreographers to explore ideas and consider the relationship between performance and contemporary politics. Reproduced within the exhibition are texts from the magazine on motherhood, feminism, racial politics, disability, and lesbian identity. Like other contemporary periodicals — for example the influential film journal Screen, in which Laura Mulvey published her essay on male gaze and female subjectivity “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in 1975 — New Dance became a crucial platform for the dissemination and development of burgeoning ideas. “New dance needs a new language,” wrote Lansley in 1977. In the inaugural issue of the magazine, she argued, “Dance like any other art form does not exist within a social or intellectual vacuum. It is subject to the same societal pressures and stimuli that impose on all areas of our lives … Writing is necessary, as a creative extension of our work, in order to project outwards, receive feedback, and communicate in depth.”

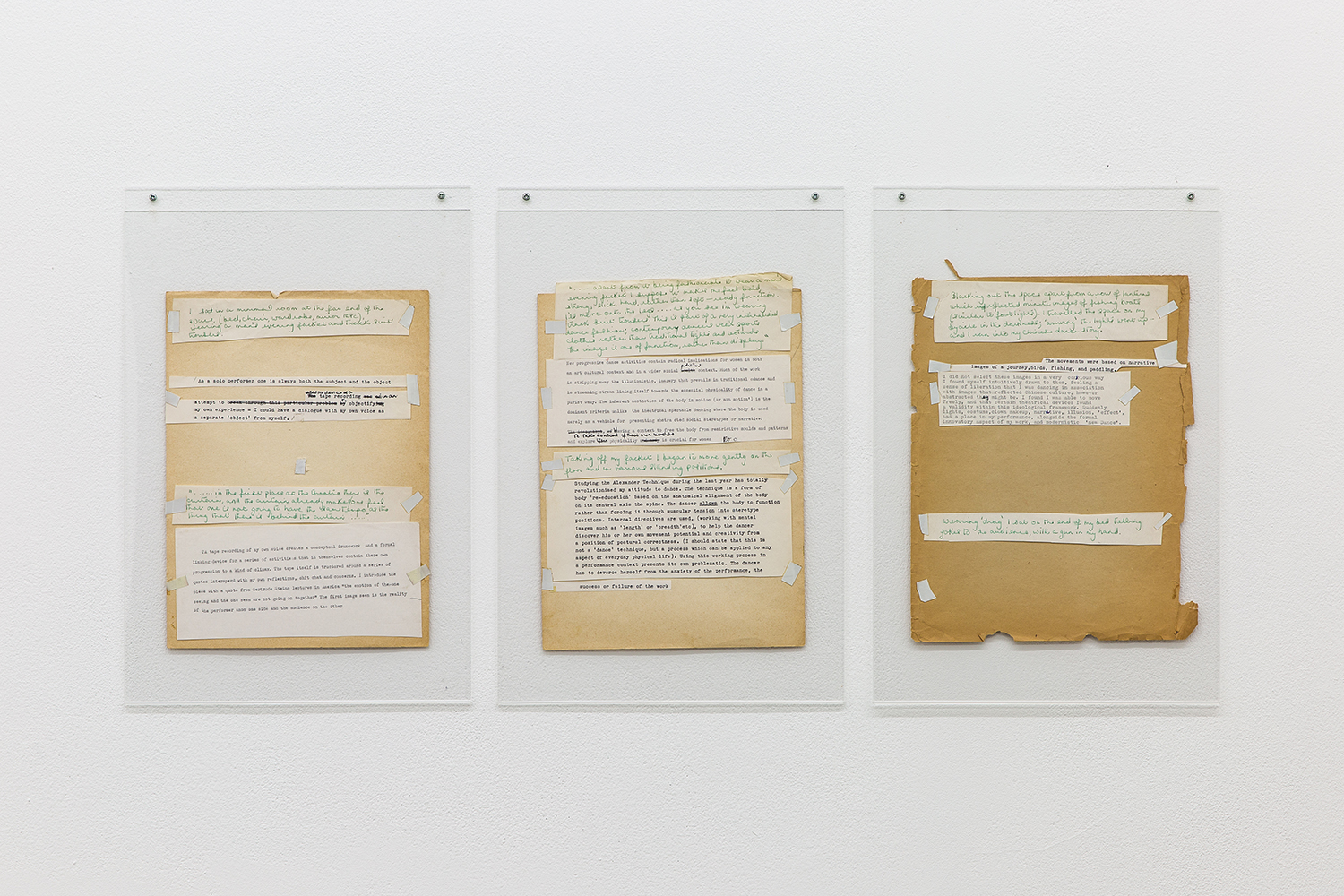

New dance sought to break down the mystification behind dance technique and was informed by notions of accessibility, diversity, and participation. The X6 collective also retrospectively interrogated their formative experiences, particularly the intensity of their classical training in ballet. They were critical of the forceful and oppressive stereotypes being enforced by traditional dance practices, seeing them as image conscious and undermining of autonomy, and therefore having negative ramifications for physical and emotional health. Prestidge had additionally trained as a gymnast, and, in an unpublished text from 1983, she talks about how the nature of competition encouraged the manipulation of one’s body “in order to cut the correct figure.” In her chapter on the X6 in Women and Dance (1992), Christy Adair writes, “They were interested in the concept of the ‘thinking body’ rather than the dancer as object.” She gives Lansley’s Dance Object (1977) as an example, in which she considered her hybrid role as “woman/dancer/artist.” Lansley’s cut-and-paste score for Dance Object is included in the exhibition, in addition to her costume: a black blazer, its pockets holding a toy gun and books by Juliet Mitchell and Mao Tse Tung. The original performance featured Lansley responding to a tape recording of her voice, and in the score, she writes, “As a solo performer one is always both the subject and the object … [I] used the device of a tape recording in an attempt to objectify my own experience — I could have a dialogue with my own voice as a separate ‘object’ from myself.”

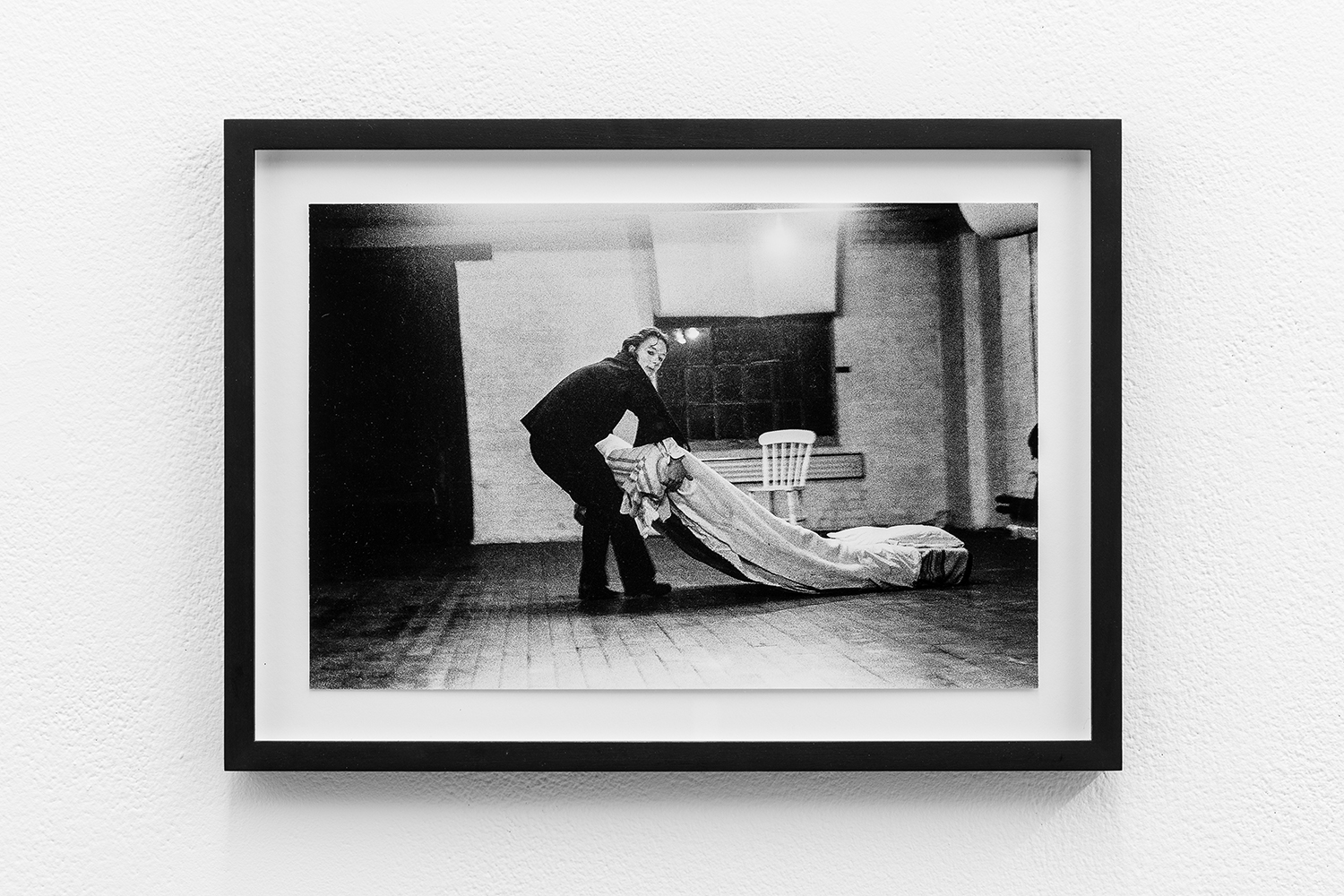

Many of X6’s sociopolitical concerns overlapped with the Women’s Liberation Movement. Artists working during the second-wave feminist movement were committed to creating a practice that reflected women’s political and social consciousness, and sought to deconstruct the image of woman as a commodity for male spectatorship. As Adair explains, “The influence of feminism is illustrated in the way they were reevaluating their bodies, their training and their performances … working away from the proscenium arch, using functional clothing rather than costume [and] finding nonhierarchal ways of working.” Men were similarly engaged in the reassessment of gender roles, with Early exploring notions of male vulnerability and emotion in his work. In 1979, while seven months pregnant, Claid performed Making a Baby at the X6 Dance Space. The work was intended as a way of demystifying stereotypes about the fragility or limitations encountered by the pregnant body. In one moment, the only record of which is a grainy image in an issue of New Dance, she balanced a dish of water on her stomach. In the dish floated a plastic swan, and when the baby kicked, the little swan bobbed along the water: a collaboration of movement with her unborn child.

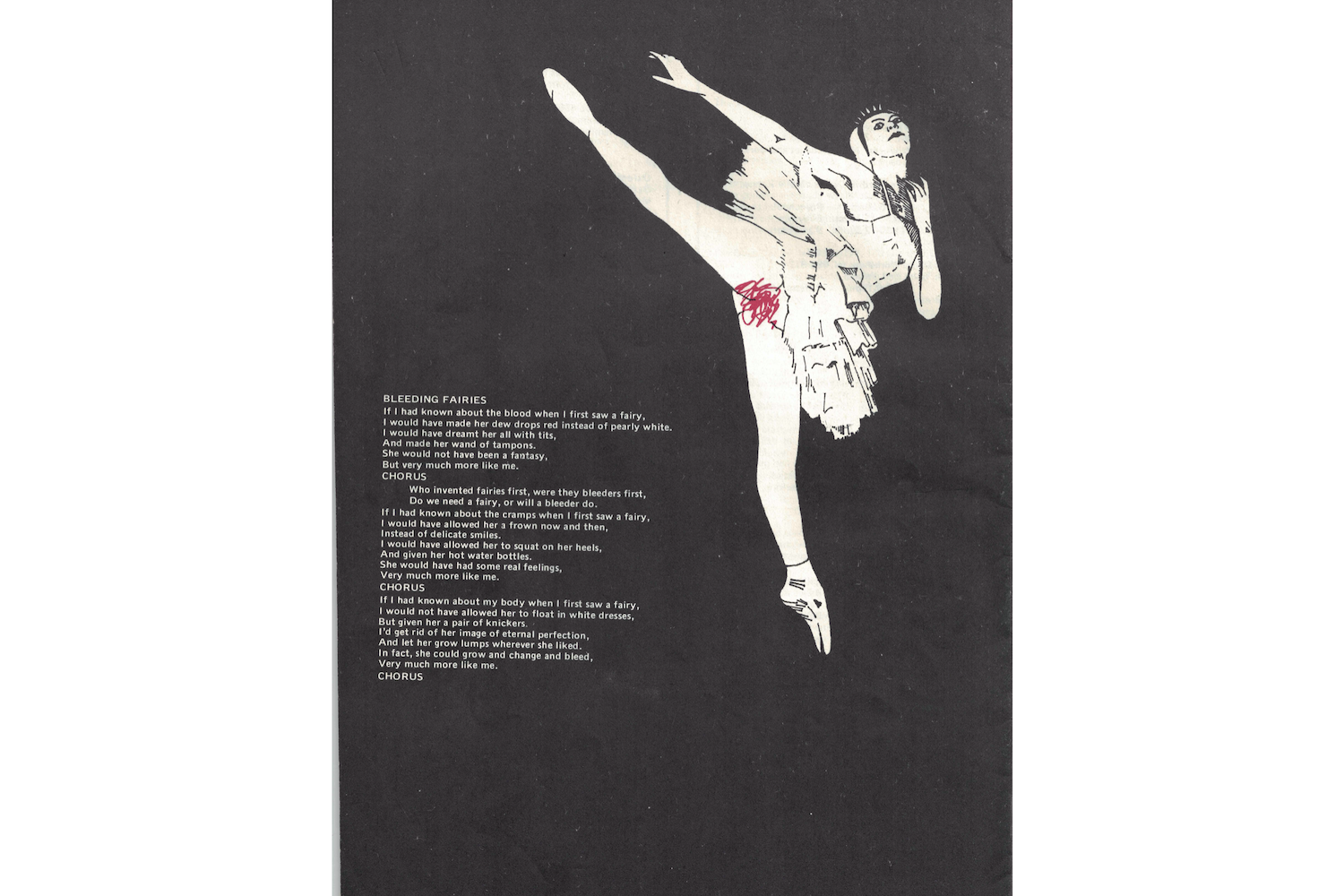

Claid, Lansley, and Prestidge had collaborated on a performance called Bleeding Fairies in 1977 as part of a women’s festival at the Drill Hall in London, in which they took stereotypical images of “sylphs, whores, and witches from traditional ballets” and subverted them through a “menstrual riot of radical feminism.” The front and back covers of issue five of New Dance in 1978 were inspired by this performance, with the back cover notoriously depicting a classical ballerina, her leg high in arabesque, with red pen scribbled over her crotch. Writing in Yes? No! Maybe… Seductive Ambiguity in Dance (2006), Claid commented, “I was particularly interested in the contradiction between the purity of the ballet image and the reality of women’s sexual, fleshy, bloody and ageing bodies … ballet, however, was never the object to be parodied; it was the lifelong performative practice of the images of beauty that had distorted our bodies. We used exaggerated ballet stereotypes to climb out of that history.”

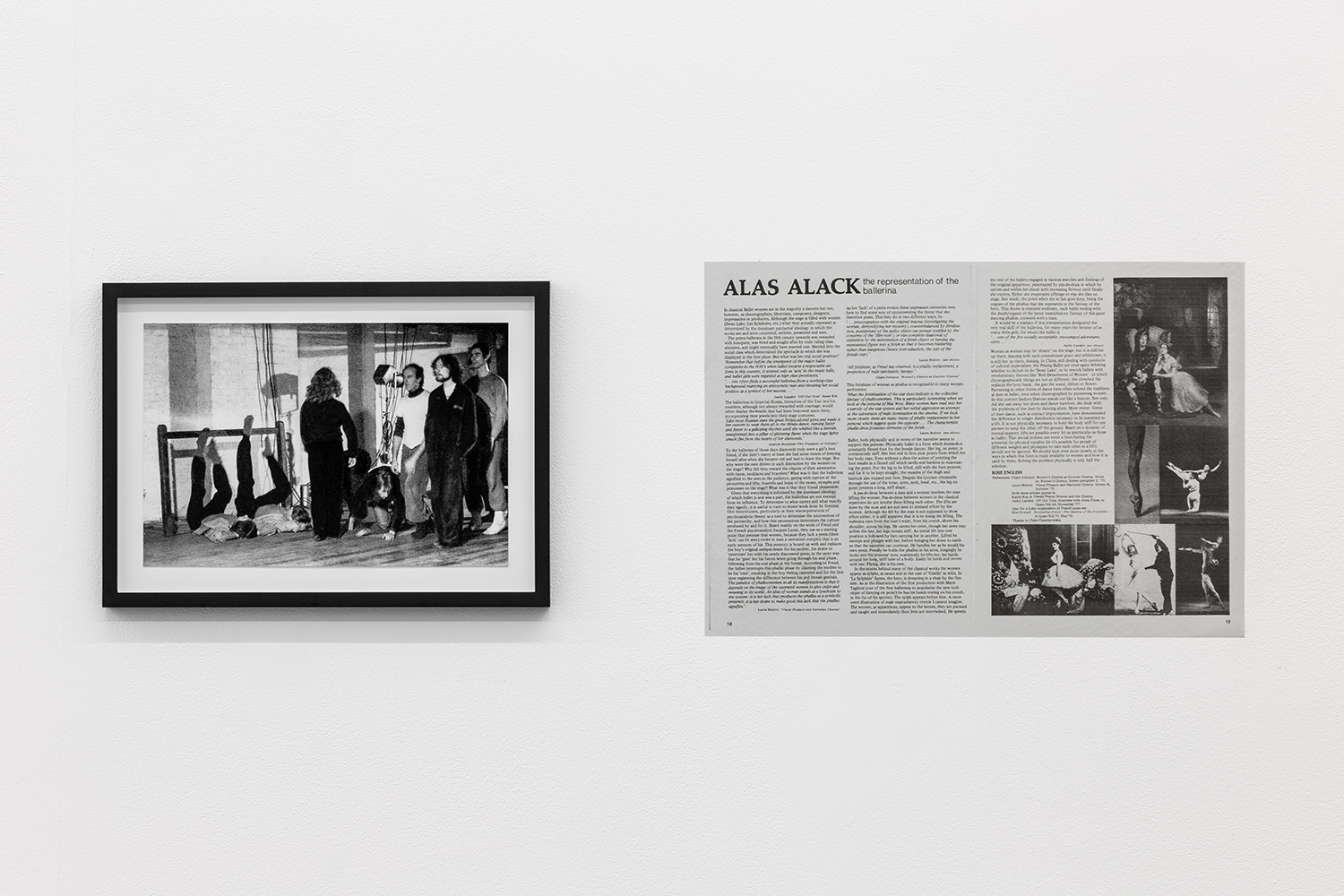

In her 1980 article “Alas Alack: The Representation of the Ballerina,” the performance artist Rose English — who collaborated with Lansley and filmmaker Sally Potter during the 1970s — explored the gendered power structures and sexual politics inherent in ballet’s pas de deux, citing Isadora Duncan as a radical forebear. “Not only did she cast away her shoes and dance barefoot,” she writes, “she dealt with the problems of the duet by dancing alone.” Contact improvisation, with its “dynamic of mutual support,” is offered by English as a partial solution, an example of which can be gleaned in the 1980 video footage of Claid rehearsing with fellow dancer Kirstie Simpson at X6 Dance Space, recorded by Stefan Szczelkun. The second video in the exhibition is from I Giselle (a deconstruction of the original nineteenth-century ballet), which was made and toured by Early and Lansley in 1980. The performance broke down traditional ballet techniques in addition to exploring the character of Giselle as a clear metaphor for the sexual oppression of women. Role reversal, physical behavior, and the subversion of archetypes were all explored.

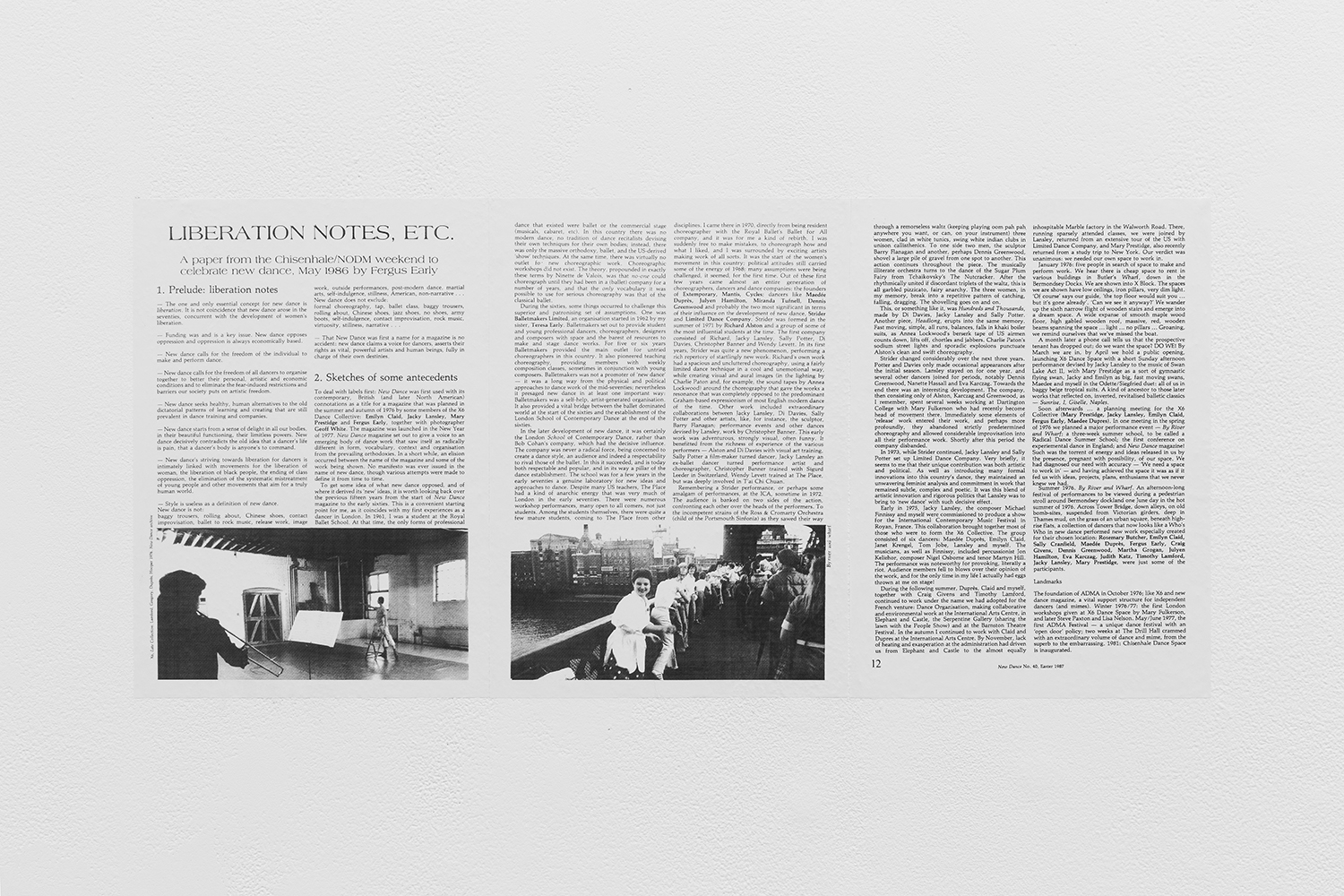

Buried subtly within the show lies the genesis for the exhibition’s subtitle: Liberation Notes. It was inspired by “Liberation Notes, etc.,” which was written by Early and given as a paper as part of a weekend event at Chisenhale Dance Space in 1986. The prelude of the text reads like a manifesto. He writes, “The one and only essential concept for new dance is liberation … New dance’s striving towards liberation for dancers is intimately linked with movements for the liberation of woman, the liberation of black people, the ending of class oppression, the elimination of the systematic mistreatment of young people and other movements that aim for a truly human world … new dance claims a voice for dancers, asserts their rights as vital, powerful artists and human beings, fully in charge of their own destinies.”