“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-second century. This year the column is curated by Barbara London and explores how artists continue to investigate sound by incorporating up-to-the-minute software and electronic apparatuses to their practice. The best sound artwork takes its audience on an inspiring journey, one that offers fresh insight into what it means to be in the world, construing something animate and distinct by means of inorganic tools. It is through the tension between the haptic and the neutral that artists and observers discover new experiences.

Two recent exhibitions by Icelander Jónsi and a current one by Oslo-based American Camille Norment reveal how innovative and impactful these two sound-based artists really are.

While they certainly differ, they also have much in common. Both utilize sound — melodic and dissonant, subtle and emphatic — in immersive installations that respond to and also transform architectural spaces. Both are acclaimed musicians and composers; their experience as live performers no doubt influences their artworks. For both, sound in their work is music, or song, and also a primary material — they sculpt with sound. Both artists’ works are also palpably soulful: they affect visitors sonically, visually, emotionally, and — very likely — spiritually too.

Jónsi is the guitarist and singer in the great Icelandic band Sigur Rós; he also enjoys a flourishing solo career. He knows a thing or two about transcendent and transportive sound; Sigur Rós songs are sonic and emotional voyages. Norment performs with the Camille Norment Trio, featuring glass armonica (an instrument with glass bowls invented by Ben Franklin in 1761), which she plays; electric guitar; and the Norwegian Hardanger fiddle. All three instruments were both celebrated and banned at different times in history. The trio’s performances are typically atmospheric and enthralling.

After a five-year hiatus Sigur Rós is back on tour, which is wonderful news for this distinctive band and its legions of fans (I’ve been an ardent fan since my first Sigur Rós concert in Reykjavik in 1999). During the hiatus, Jónsi, known for playing electric guitar with a cello bow and singing in his ethereal, soaring falsetto, often in the invented gibberish language Vonlenska (English translation: Hopelandic), surprisingly emerged as a sound and visual artist, with two solo exhibitions at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, one in Los Angeles in 2019 and the other in New York in 2021.

Traveling to Los Angeles for the first exhibition, I admit I was skeptical about a rock star suddenly becoming a gallery artist. My skepticism immediately vanished when I encountered the exhibition, which was wonderful. Three installations (all 2019) featured layered, alluring sound, presented in different ways, in strikingly visual environments. Each installation was infused with a unique scent concocted by the artist; this was a multisensory show. In downtown Reykjavik, Jónsi and his sisters have the fantastic shop Fischersund, which purveys his homemade scents.

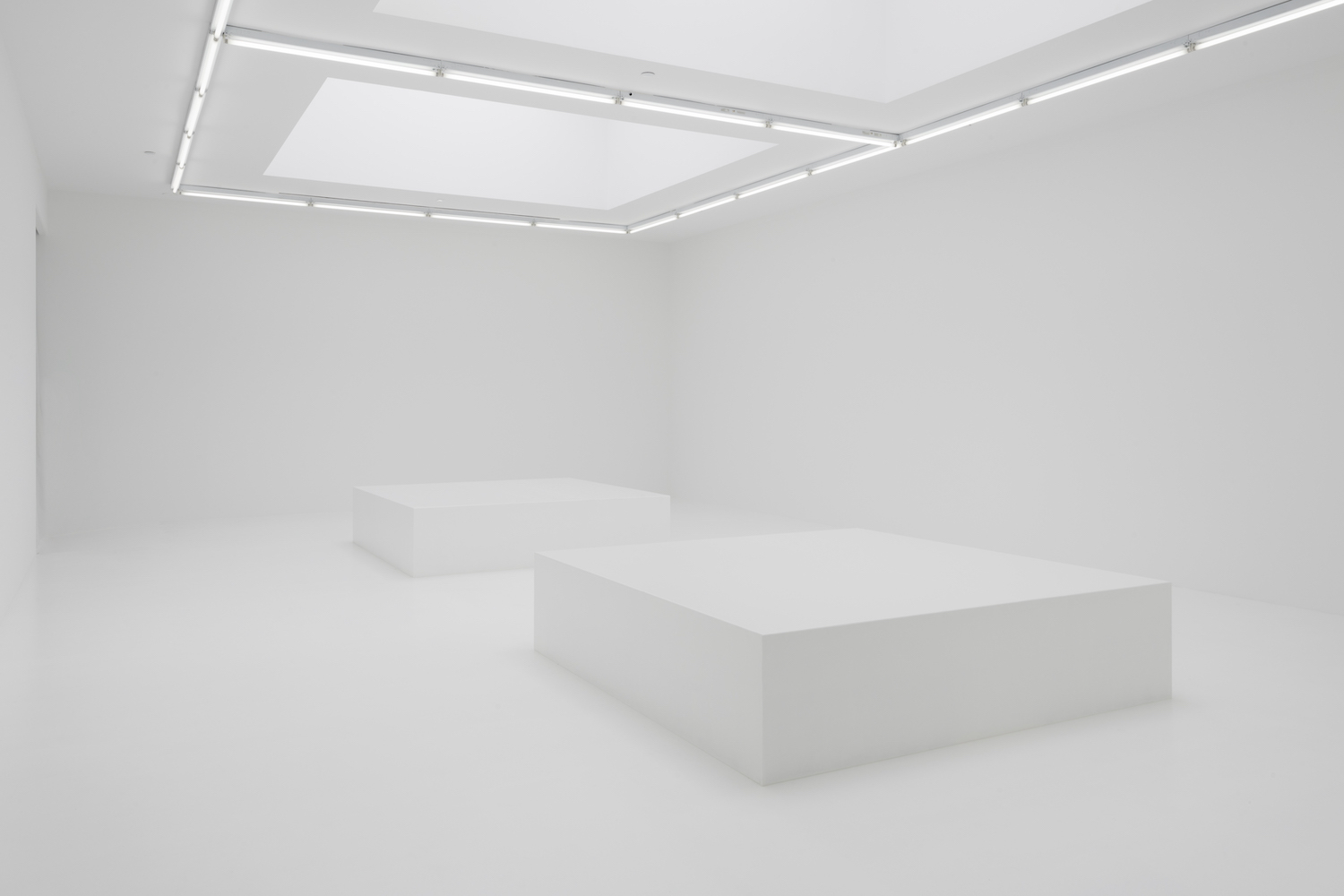

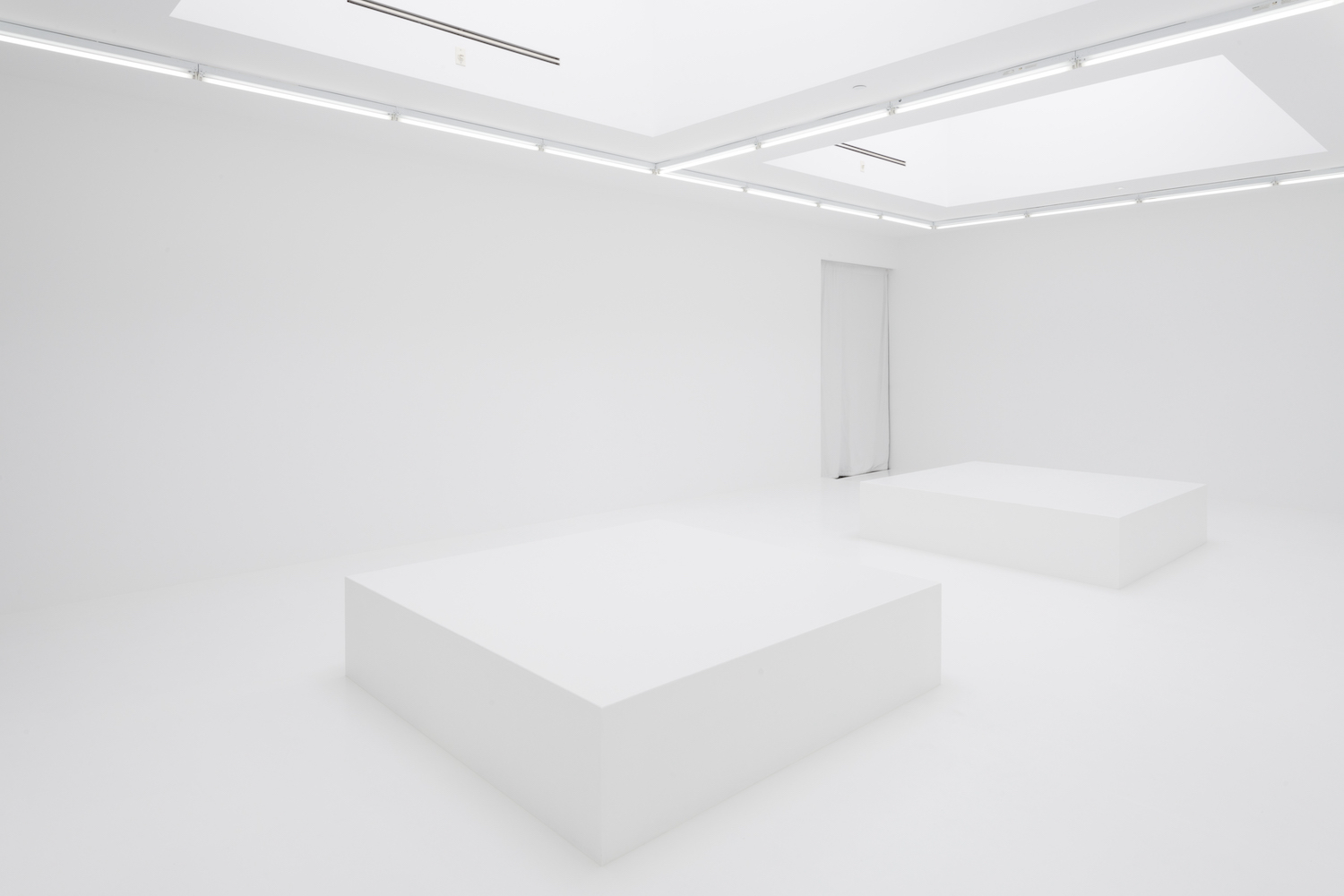

The centerpiece, in which people tended to linger for a long while, was Hvítblinda (Whiteout). The gallery’s main space was empty, save for two platforms on which one could sit or recline, and startlingly white. One had to don white booties to enter this pristine space, which felt heavenly, vaguely eerie, otherworldly, and altogether elsewhere, a bit like the rooms on Jupiter near the end of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

What Jónsi calls “a five-act soundtrack” emanated from ten hidden speakers and two subwoofers; the soundtrack combines Jónsi’s remarkable, often angelic voice, synthesized sounds, and field recordings, including of wind and snow. LED lighting overhead responded to the soundtrack, alternately brightening and dimming. The scent was ozone.

Jónsi turned the whole, bright white space into a multifaceted instrument emitting a lush, sometimes mysterious, and often rapturous soundtrack, which at times resembled a full choir, interspersed with nature sounds and those seemingly from the remote universe. The emotion-inducing soundtrack washed over viewers as they slowly moved through the space or lay on one of the platforms while feeling the vibrations (subwoofers were inside); one heard Jónsi’s soundtrack but also felt it on and within one’s body.

This indoor installation with its varied sounds and ozone scent linked humans and nature; that’s something Sigur Rós also does, channeling, in however abstracted ways, potent natural forces (so prevalent in Iceland) into their music: sweeping wind, surging rivers, seething magma, ocean waves. The installation’s title also evokes the Icelandic highlands where whiteouts from thick fog and driving snow are commonplace, sometimes dangerous, and even deadly. Snow fields and glacial ice were also possible references.

Two years later, in New York, Jónsi’s exhibition furthered the connection between his artworks and nature. Titled “Obsidian,” after the black glassy material formed by cooling lava, the exhibition coincided with the release of Jónsi’s excellent solo album of the same title.

Both exhibition and album were inspired by the March 19, 2021, eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano a mere twenty-five miles from Reykjavik (most eruptions in volcanic Iceland occur in remote areas far from the capital region), which continued for six months and riveted the whole nation. People flocked to the site to witness this awesome geologic event.

Having relocated to Los Angeles, Jónsi couldn’t return to Iceland due to COVID-19 travel restrictions; he was separated from family and friends — and really his whole country — at this crucial time. He responded from afar, crafting an installation not specifically about Fagradalsfjall but instead arising from his imagination of a volcano with all its primal power.

The centerpiece was Hrafntinna (Obsidian) (2021), in the darkened first-floor space — so dark that at first I could barely see a thing. As my eyes slowly adjusted, I began to make out more than two-hundred speakers arrayed in a large arc around a black plinth on which one could sit or recline; they seemed like the walls of a cave or, it turns out, the interior of a volcano. Overhead was an illuminated disk, like a volcano’s vent seen from below; it also suggested the moon, sun, and sky. The effect was of being inside a volcano, not looking at one from afar. Light glinting off the speakers made them look like reflective obsidian.

The enveloping soundtrack, swelling and diminishing while moving around the room, consisted of Jónsi’s voice, musical tones, mechanical sounds, and no doubt many others. One heard what resembled a majestic, full-throated choir as well as breathing, whispering, the sound of clicking rocks, and wind. Every now and then a loud roar evoked gushing lava while the overhead light alternately intensified and dimmed. For me the whole experience was transfixing.

Camille Norment’s exhibition “Plexus” at Dia Art Foundation in Chelsea is in two parts, each in a separate, cavernous exhibition space connected by a door. In the first part a gleaming brass sculpture is in the middle of the room; it could be an inverted bell, bowl, perhaps a Tibetan or Himalayan singing bowl, or an outsize version of a musical horn. Above, descending from the ceiling, is a teardrop form, also suggesting a clapper as well as a pendant.

Both brass sculptures are flat-out gorgeous. Bedazzling in the mostly empty room, and with a reverential air, they summon and welcome viewers while reflecting light and viewers on their surfaces. Above, near the ceiling, are four microphones on long poles, each pointed toward the objects, creating what the exhibition text calls “an autonomous feedback loop” with ambient sound directed toward the sculptures, which amplify it and cast it back into the space.

The brass sculptures resonate with mesmerizing sounds which spread through the room. The checklist notes sine waves as one of the art materials; that’s about as pure and crystalline as things get. The text also notes that the sound contains “spectral artifacts” and “static” of 1960s and ’70s radio broadcasts, including those addressing “social and environmental struggles”; I couldn’t make this out very well. The high-pitched sounds are often subtle, but at other times pronounced and insistent. They also constantly change with the movement of viewers, whether one is up close or distant, and with flowing wind as the doors open and close. Viewers here are not just consumers but also (as I experienced) rapt participants. They change the music, and the music changes them.

The installation in the next room is much more elaborate, and specifically responds to the architecture, especially the impressive, vaulted ceiling full of dark brown wooden beams that loosely resemble the ribbing of a ship. Similarly colored beams are arrayed in different configurations as if they’ve spilled from the ceiling — they are leaning against the walls and gathered on the floor. Obviously precisely arranged, they also suggest haphazard industrial materials, perhaps from a demolished building, the aftermath of a severe storm, or some other trauma. This neighborhood was walloped by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, an extremely destructive storm linked to global warming. It has also gone through many convulsions and incarnations through the decades, with buildings torn down and new ones erected, people displaced and new ones arriving.

The entangled wooden beams also function as speakers, emitting a captivating, ever-changing choral soundtrack in twelve voices, both female and male, along with the intermittent sound of grinding teeth, which introduces a note of anxiety. The voices are low, somber, sometimes droning and mournful but also very lovely, even uplifting. One can sit or lie on the beams, surrendering to the flow of the music, hearing it as it travels — over there, across the room, behind one’s back, then suddenly right here beneath one, under this vibrating beam, which makes things suddenly intimate.