I tend not to be too excited about Monferrato, a hilly area in northwestern Italy about an hour outside Turin.

After going to visit Orsolina28, I finally realized that it was provincial and superficial of me to think that the place was in the middle of nowhere and depressing. Yes, when it’s hot you melt into the landscape, and when it’s cold you hibernate, but isn’t New York the same?

But, back to Orsolina28: the setting was once a convent, home to Ursuline nuns. It now belongs to Michele Denegri and Simony Monteiro, ex dancer and visionary. The place became an art foundation in 2016 with a focus on dance, performance, and mental and physical well-being.

It features indoor and outdoor dance studios, an amphitheater surrounded by organic vineyards and vegetable gardens, a tropical greenhouse (with bonsais trees), and a fully equipped glamping. An actual paradise in a place I considered to be deserted.

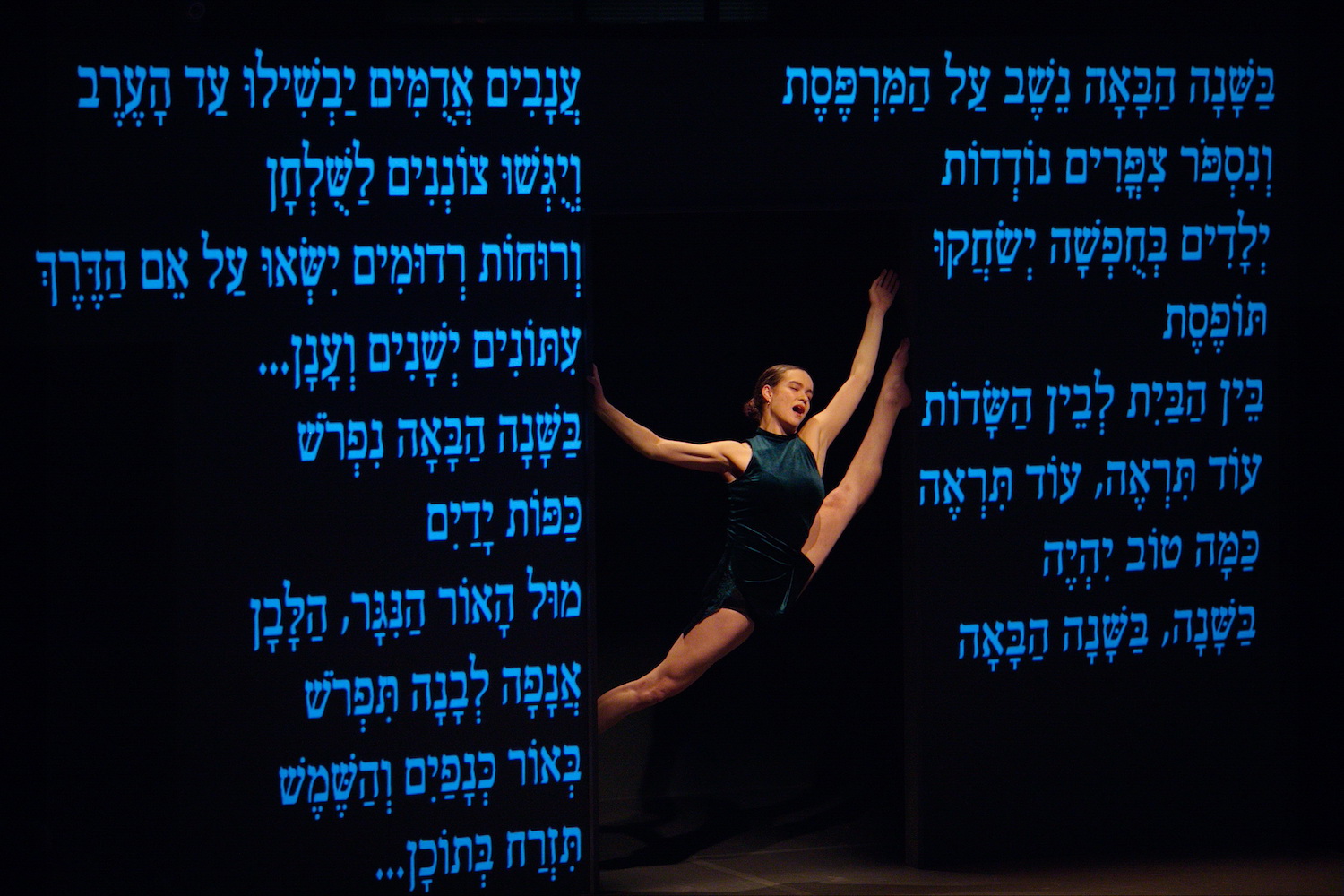

In June of this year, a restaurant, indoor swimming pools, and “The Eye” will open. The latter is a dance theater in the middle of the greenery with collapsible walls allowing for fully open-air seating and performance spaces. It was designed by Monteiro, Denegri, and choreographer Ohad Naharin. This last was the reason why I was invited to visit O28. He founded the Batsheva Dance School and has more recently embarked on a new project that allows mortals like me to dance and feel in charge of their lives. And so, I did. The workshop began with a screening of the film Hora (2022), based on Naharin’s ballet of the same name. The sixty-minute film, with an engaging and sometimes distressing soundtrack by Isao Tomita, has been described as a “dancing catwalk,” due to its use of what some would call a scenographic dance cliché: dancers in a black bodysuits on a black background. Tomita’s score includes a montage of electronically altered bits of classical music (“Ride of the Valkyries,” “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” etc.), and the choreography samples, in no apparently logical order, just about every movement one could imagine: snake hips, dog paws, chicken-head-jerks, plus tilts and grabs and falls and flutterings for which I can find no vocabulary. This is not a nationalistic folk dance, as the title may suggest. On the contrary, it is a pretty standard piece of “contemporary dance” — an admixture of 1930s-through-1950s mid-modern and 1950s-and-onward late modern.

Gaga People

“Let’s all admit that life is difficult,” he begins, “but that doesn’t mean we should get crushed by it. We have to find a way to balance stamina, strength, awareness, delicacy.”

Once Naharin found his place in the middle of the floor, surrounded by so-called “gaga people” — nonprofessional dancers who become infused with the choreographer’s doctrine and dance techniques — he began to move and explain the feeling of movement, the relationship with space with a focus on the pleasure of stretching and curving and drawing lines and feeling limitless.

Movement is still underexplored in our post-coronacene world. There can be a disconnect between body awareness and mindfulness: most humans master one side or the other, and a true alliance between the mental and physical is often abandoned.

The performance of movement, on the other hand, plays a prominent role nowadays; we don’t just move but we display our movement through devices and share it.

When in a room with Naharin and seventy other people interacting with each other, it’s difficult to move carelessly and be transported by his words, until it isn’t.

The choreographer’s guru vibe softly embraces even the most stiff and nervous souls, until everyone is happy to be sharing their private journey with perfect strangers.

The secret is the structure: he begins with gentle humor and ends with awareness. That’s what he emanates. He wants people to dance in their own element and yet create order, a discipline of their own. There is a lot of movement-based theory behind Naharin’s methodology. There is very little imitation, and a lot of making your own choreography from scratch even while learning. The approach is pleasurable; as the person in charge starts experimenting with movement and its possibilities, they make otherwise goofy moves look sexy and controlled.

Movement can heal. It can instill balance, strength, and longevity. Naharin began teaching after sustaining many injuries as a dancer. He discovered that he could still exceed the limits he felt while moving; the more he ages, he says, the more he discovers something new about his body and how to beat the boundaries of stiffness. He doesn’t even worry about becoming wheelchair-bound, as he might discover parts of his body he wasn’t yet acquainted with.

Proximity

Naharin’s choreographies play with the audience. Attaining this intimacy in larger theaters is more of a challenge.

Small gestures, details, and the control of those details are his greatest strengths. Hence, playing with an audience in an intimate setting allows him to give back more. The granular textures of his gestures become visible at that smaller scale, without the need to zoom in. In a larger space, one always needs to zoom in, and that becomes the first obstacle.

Intimacy when shared can initially be scary, but eventually it becomes very exciting. It’s like speaking loudly versus speaking very quietly: the audience becomes closer, feels a more intimate exchange.

At the beginning of each show, a man, wearing high heels, comes out from behind the curtains and kindly asks the audience, in both English and Arabic, to switch off their phones. This breaks the ice. His slightly absurd manner and high, intentionally affected tone of voice puts people immediately at ease.

Intimacy always creates strong feelings, and Naharin describes himself as a junky for emotions. His ideal choreographic and pedagogical trinity is the power of imagination (mind), passion (soul), and skill (body). Prioritizing emotions, and showing them through movement and dance is a language we almost forgot about and Naharin’s method can be one of the answers.

Ohad Naharin’s 2019 is performed live by the Batsheva Dance Company on June 18th and 19th at Orsolina28.