A monthly review of global art news from an admittedly fallible viewpoint.

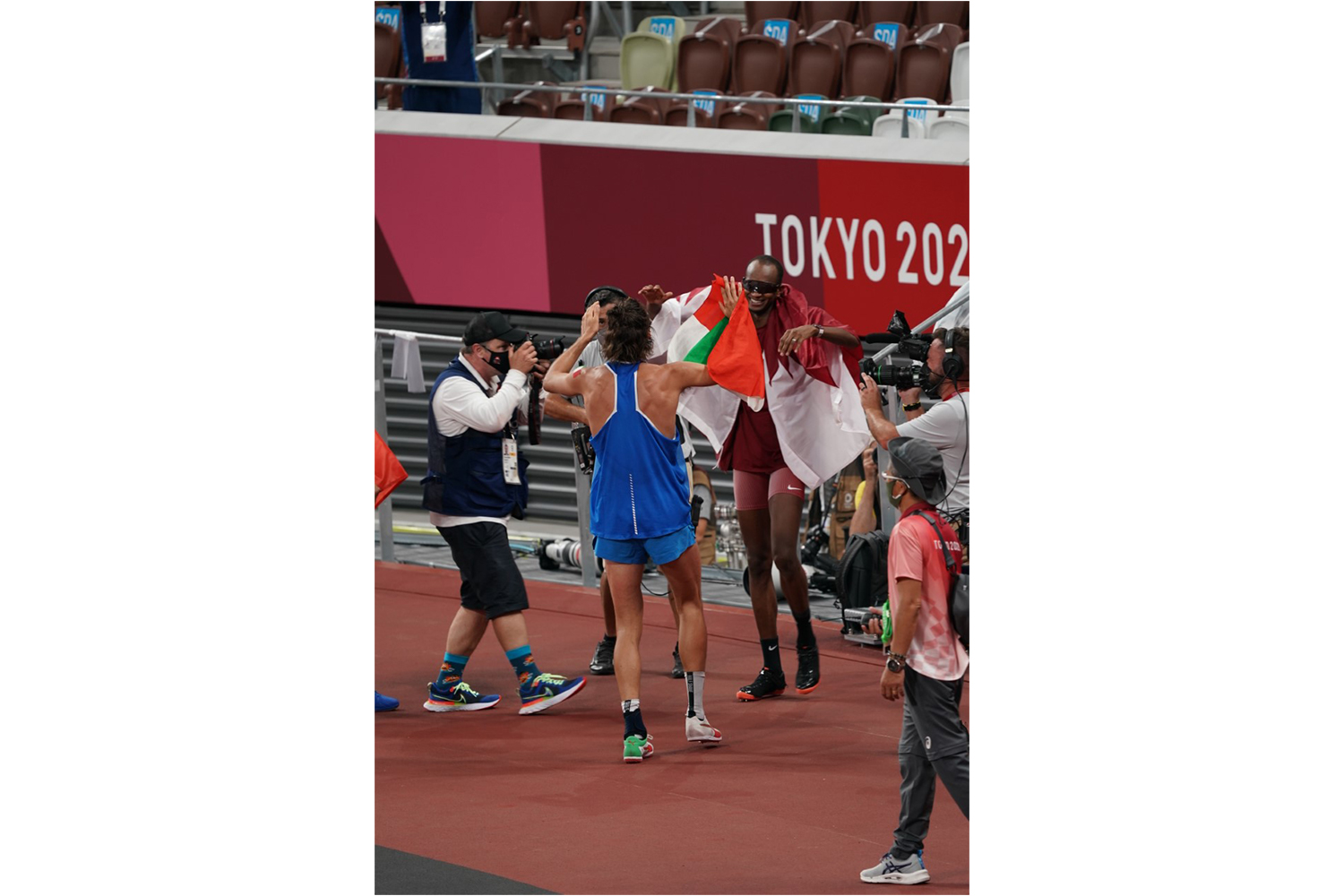

The men’s 2020 Olympic high jump final. Gianmarco Tamberi and Mutaz Barshim were tied at 2.37 meters. Both athletes were plagued by injury in the lead up to Tokyo. Five years earlier, Tamberi broke his ankle just days before the Rio Olympics. He saved his cast and before his final attempt laid it at start of his run-up, felted tipped on, “Road to 2020”. “2020” crossed out for “2021”, after COVID delayed the games. Neither could push any harder. The official gave them the option of a “jump-off.” The bar would go down to the last cleared height, then it’s incrementally re-raised until someone’s body breaks down. Barshim asked, “Can we have two golds?” “It’s possible…” Before the official could finish, Tamberi leapt into Barshim’s arms.

More and more, artists and writers refuse to compete against each other in jump-off prize draws. Like Barshim and Tamberi, two years ago, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo, and Tai Shani were announced joint winners of the Turner Prize after the four nominees declared themselves a collective. In a joint address, the artists said competitions “divide and individualize” and “we wanted to make a statement of commonality, multiplicity, and solidarity.”

Never a Fair and Open Field

Artists prizes like writing prizes, the most reputable, best paid prizes are awarded by judge nomination. By contrast, less publicized, less well-funded prizes, usually only open to artists and writers with a few years’ experience, entrants are assessed on application, a boring, admin-heavy process, unfairly placing the highest time costs on early-career professionals, who stand far slimmer chance of recognition or remuneration. While artists might be examined on existing portfolios, art writers usually have to produce new exhibition reviews or essays on spec, more than likely never to see the light of day. Only the winner is paid, often barely above market rate. Sometimes runners-up receive a small fee, but otherwise the rest write to maintain the prize’s illusion of competitiveness. “The response this year has been overwhelming. We’ve had [insert number here] applications.”

The Burlington Magazine’s Contemporary Art Writing Prize refers to entrants as “contenders,” and Art Review’s JJ Charlesworth claims prizes sort “the best and the not-quite-so-good,” but prizes are never a fair and open field: they only ever draw from a limited talent pool. Prizes are discriminately weighted in favor of applicants with more expendable time, who can afford to produce work they’re unlikely to be paid for, narrowing potential participation from working-class people.

The Limits of Cultural Exchange

Various international writing prizes have been established to help share different perspectives from around the world. The International Association of Art Critics hosts two global prizes: the Distinguished Prize and a Young Critics Prize. The Young Critics Prize is usually open to applicants from all countries, but texts have to be written in English or sent with an English translation (except the prize’s first edition, which allowed both English and Spanish submissions). This year, 2021, the competition was only open to applicants from Armenia, Bulgaria, Greece, or Turkey, but again all entries had to be written in English, flattening the complexities of writers’ national cultures. Sayings and expressions, irony and sarcasm, metaphors and imagery are often lost in translation. Clearly it would be impossible to assemble a judging panel where every juror speaks every language, but again, by attempting to measure everyone by the same yardstick, the prize format not only limits cultural exchange but also quality of response.

Prizes hold individuals up as often empty symbols of progress, and ultimately, cultural exchange lacks any radical potential to decentralize US-European museums and galleries, magazines and journals. To shift power and change the shape of discussion, arts organizations need to prioritize, not simply spotlight, marginalized art and writing, provide consistent commissioned opportunities not one-off, annual funding dumps for a winner and maybe a few runners-up. Admittedly, the choice isn’t necessarily between prizes and progress. For example, C Magazine gives to voice First Nations, Inuit, and Métis art and resistance and also co-hosts an Indigenous Art Writing Award with the Indigenous Curatorial Collective. Still, if we’re stuck with prizes, they have to be as well as not instead of real change.

Grants, Mentoring, and Residencies

Other ways to support writing include grants, residencies, and mentorships. Grant recipients are sometimes required to produce predefined content, often implicitly promoting the grant provider, or submit a detailed, fully-costed project outline, again draining, unpaid work which eats into otherwise billable time. However, critic duo White Pube host a monthly “no strings attached” grant for working-class, early-career UK writers. Funding is awarded via a mix of nominations and informal email applications (nomination-only would completely remove the burden from writers), and there are no expected outcomes, allowing grantees to spend the money however they like.

Sometimes interchangeable with grants, residencies provide an opportunity to develop some form of artistic practice over a prolonged period of time, often with a single organization. Momus, another Canadian art publication, runs a two-week, twice-annual Emerging Critics Residency. Tuition fees are $600 CAD, with a limited number of subsidized places also available. Led by top critics, the course covers pressing debates around contemporary art and the practicalities of print and digital publishing. There is huge pressure to specialize early, and while participants will take a lot from this residency and others like it, it’s important to avoid investing too heavily in a single discipline. A US survey conduct-ed by 2017 Nieman Foundation Fellow Mary Louise Schumacher found that 54% of visual arts journalists earned less than $20,000 from writing and 80% worked additional jobs to subsidize their income. To regularly produce art criticism, you will likely need other revenue streams: editing, teaching, gallery administration, invigilation, for example.

In the US, Eyebeam and Momus co-host a Critical Writing Fellowship. Whereas AICA-UK have no stipend with their Emerging Art Writers Fellowships, the Eyebeam-Momus mentor program, an eight-month fellowship, comes with $4,000 USD honorarium. Both offer editorial guidance, networking opportunities, and detailed writing feedback from distinguished art critics but more writers would benefit if information was unmediated by mentors, and free and openly available online.

Schumacher’s survey found that 56% of visual arts journalists work freelance without contract. Freelance writing is isolating and, like prizes, encourages you to think of people in the same field as potential competitors, fighting over a limited number of paid opportunities. Freelancers often feel reluctant to share editors’ email addresses or discuss finances because they worry they might lose favor with existing employers. However, it’s only when freelancers pool resources that they win higher wages. For example, the UK National Union of Journalists has a database called Rate for the Job, where writers can anonymously share rates they have achieved, providing a baseline from which to negotiate up. Writers and artists have to continue to refuse the jump-off. Together, never lower, only higher.