Global Art Market News, Commentaries, and Critiques. A Column by Stefano Baia Curioni.

Everyone can draw. Before we learn how to write our name, we take markers in our hands and trace lines on a paper surface. Then we grow older, and most often we stop practicing and we forget this unpretentious, simple art. Artists enroll in the academy to learn the correct way to draw — usually from plaster casts or nudes — before they begin to unlearn again. Designers and architects, those sublime draftsmen, are taught to alternate between sketching freehand and using the tools of the trade — compass or software. Finally, fashion designers master the art of the portfolio, a magic box filled with sheets of paper covered with colorful model drawings. After all, the era of Apple is the era of design, a new age of disegno. For Renaissance humanists, disegno was both the mental idea and its embodiment on paper; in short, the mark of an author. For us, while drawing remains a universal language of communication, its market value is volatile and arbitrary. Everyone may draw, but not everyone can sell their drawings.

A market for drawings in contemporary art began early on. In 1908, Georgia O’Keeffe was a twenty-year-old student at the Art Students League in New York, visiting an exhibition of recent drawings by Auguste Rodin held in the gallery run by Alfred Stieglitz at 291 Fifth Avenue. The quasi-abstract sketches on show made a great impression on her, revealing the thinking hand of a powerful sculptor and an audacious human being. Rodin’s nude drawings, so energetic and summary, sparked debates in the provincial American art world where works on paper, including photographs by Stieglitz and his friends, were still striving to be recognized as artworks in their own right. (And to think that today, counterfeits of Rodin’s drawings are so common that dealers are always skeptical about them!)

Then, the groundbreaking exhibition “Drawing Now: 1955–1975,” curated by Bernice Rose in 1976–77, pushed the boundaries of the medium even further, demonstrating how much conceptual and minimal art was based on unassuming, restrained works on paper. In 1977, Marian Goodman opened her gallery in New York with a show of Marcel Broodthaers’s drawings and objects, after various experiments in publishing. To this day, the gallery’s identity is still characterized by an interest in the timelessness of media and their apparent decline. Once we assume that drawing is both an everlasting tool and the most ephemeral, fragile medium, we become aware of its appeal: drawings can be seen alternately as studies for the final work, as personal notations of the artist’s innermost ideas, or as autonomous pieces which do not require definitions.

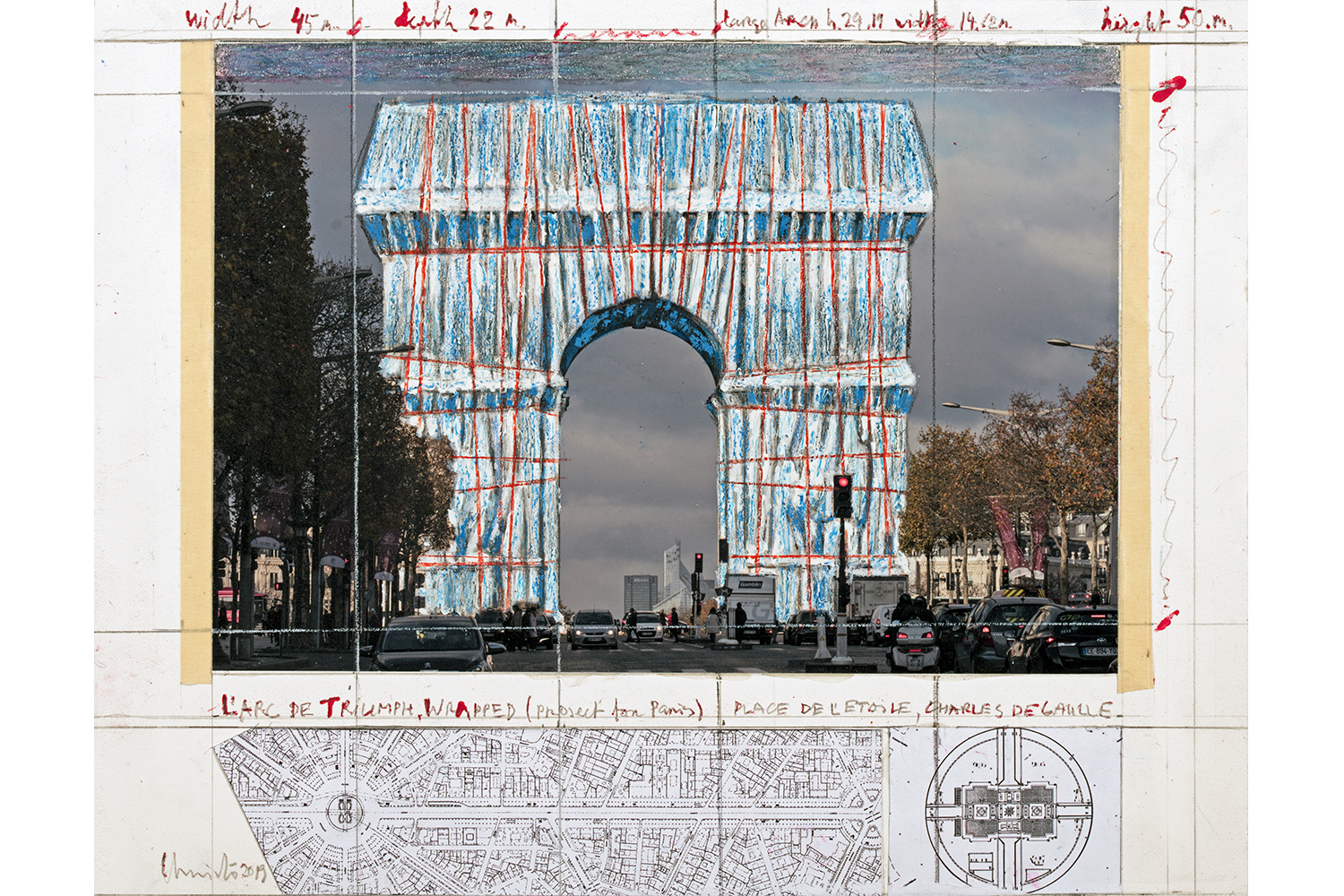

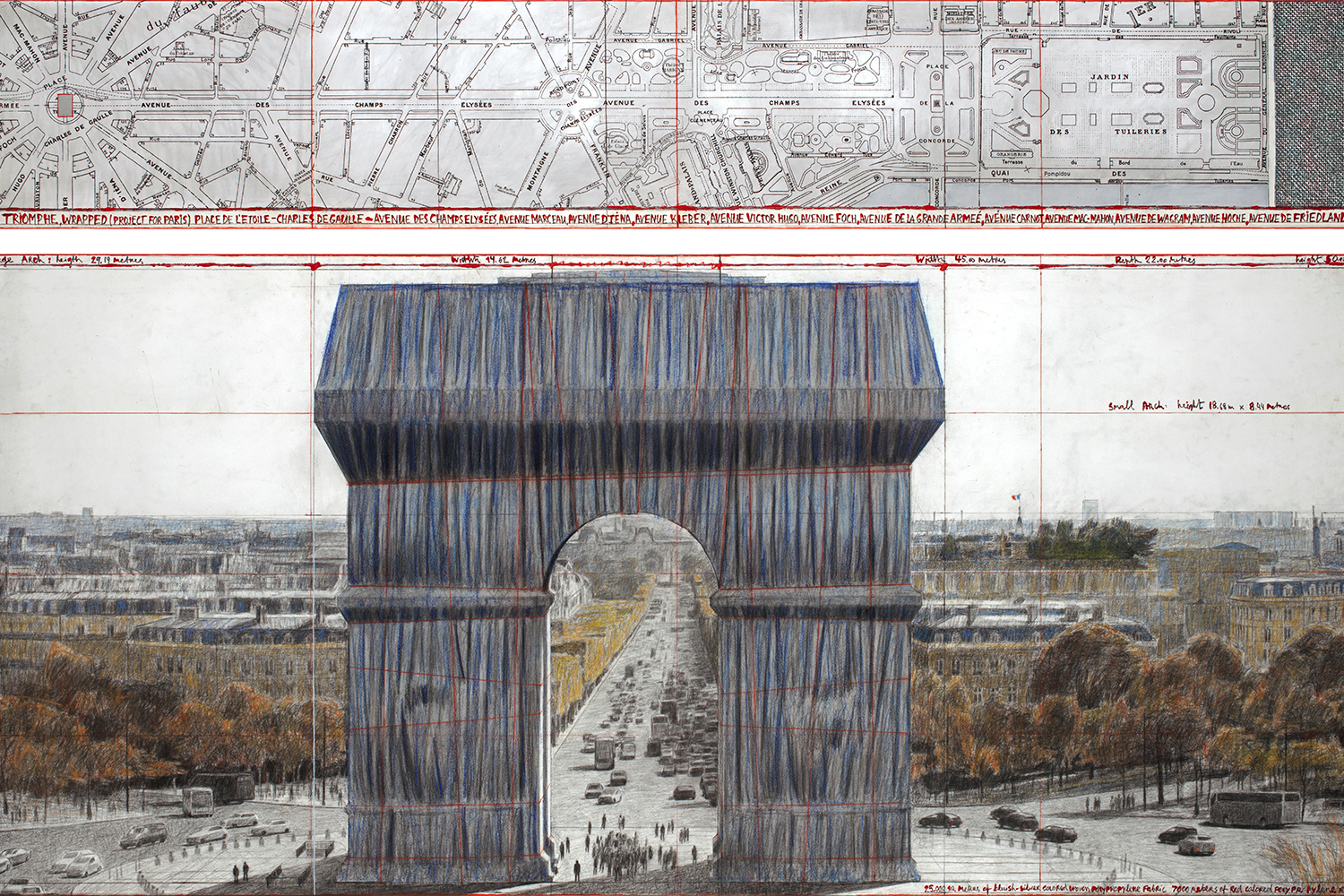

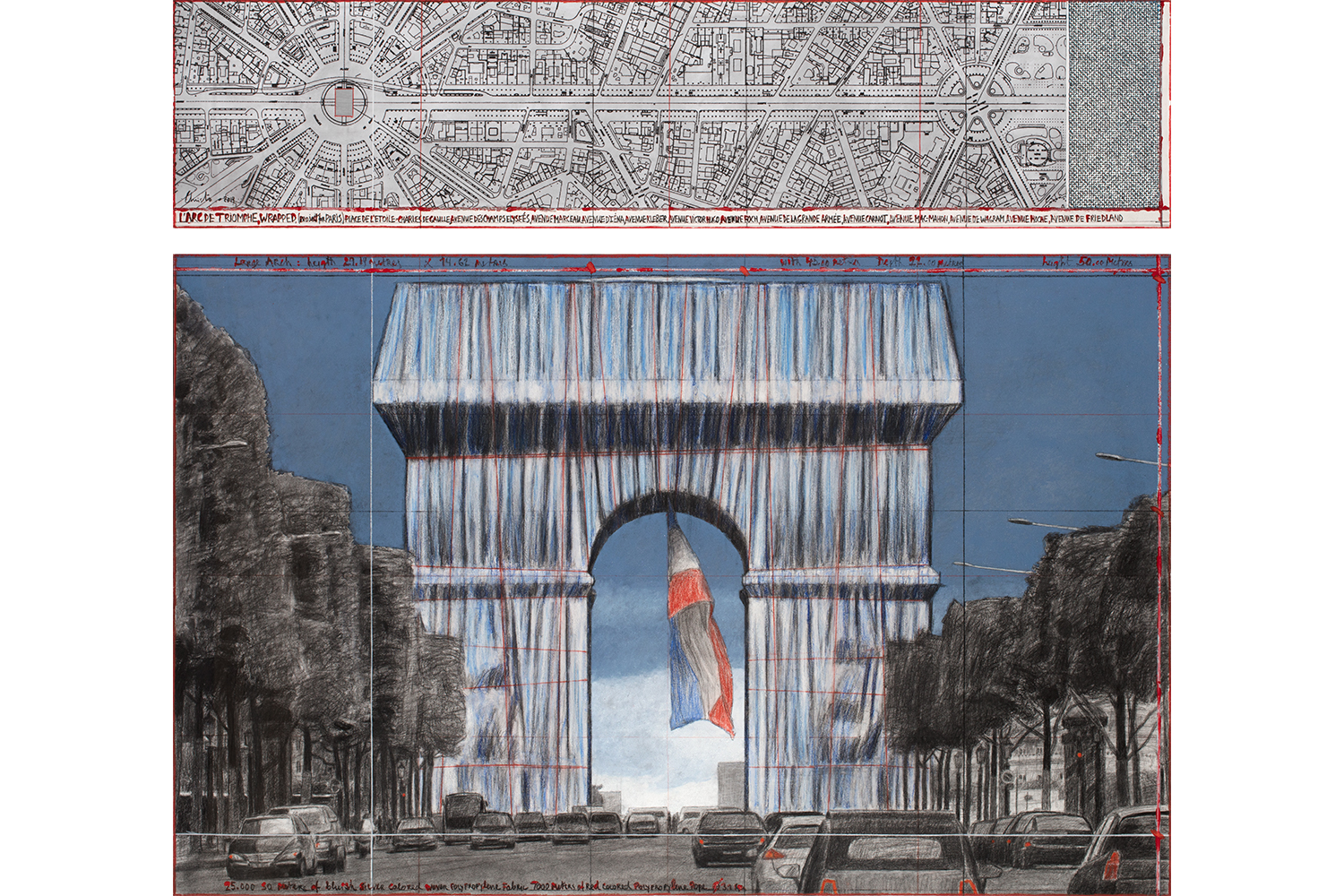

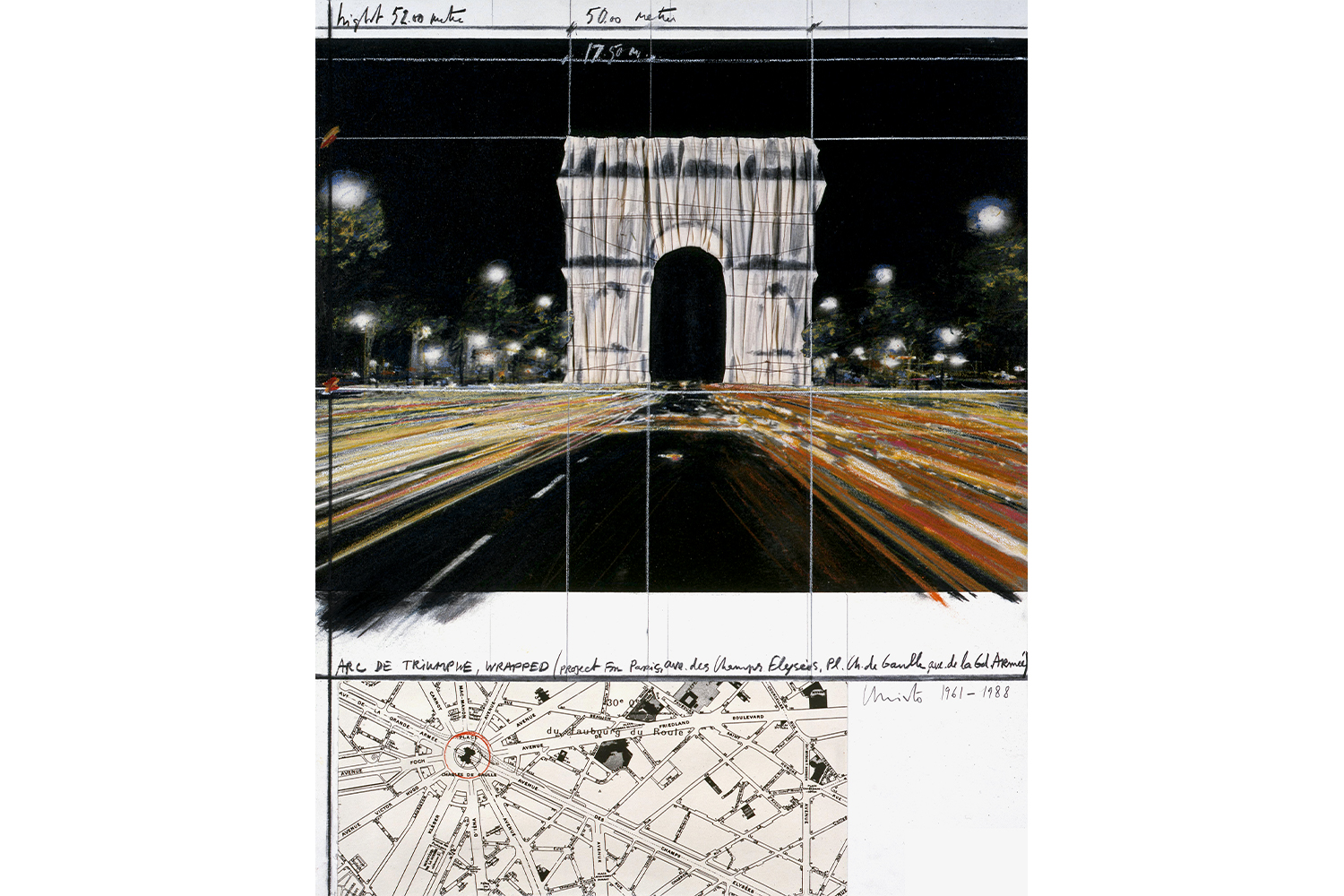

Some artists are able to exploit these elusive qualities: Christo sold his works on paper — sketches drawn in colored chalk over photographs of his works, or sketches in chalk with pieces of fabric — to fund the realization of his complex installations. Often referred to as preliminary studies, his drawings are at the same time open-ended works and carefully calculated pictures, with colorful pieces of cloth sewn into the paper emerging from the black-and-white background. In short, these studies are made for a functional purpose and with an eye to aesthetic quality. Above all, drawings are the unexpected mark of an artist’s intention and passing emotion. Since drawing captures an artist’s signature gestures, sales of contemporary drawings will always depend on the possibility of capitalizing on an artist’s name. In September, twenty-five studies for the wrapping of the Arc de triomphe in Paris, planned by Christo for decades and left unrealized before his death last year, will be sold in Paris, most expected to fetch very high prices (between $150,000 and $2 million each).

The pandemic has reinforced the primacy of drawing. When the Milanese gallery Vistamarestudio opened its first group show after the pandemic, titling it “Le Arti 1964–2020: The Practice of Drawing,” it became clear that, after a time of crisis, the more personal, introspective, and cheaper art of drawing could reunite artists with their clients. Drawing was understood as an invitation to post-crisis renewal through experimentation and freedom, its ambiguity becoming its strength. From Pino Pascali to Andrea Romano, the modernist line inaugurated by Rodin and continued by conceptual and minimalist artists from the ’60s seems to be thriving. Most of all, in the age of the permanent crossover between art, design, fashion, engineering, and all forms of creation based on drawing (oftentimes collaborative!), this accessible medium, apparently revealing the author’s innermost individuality, becomes the reminder of the modern glorification of authorship, this evasive yet dominant concept. The market loves this art of deception.

Marseille, July 19, 2021