Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

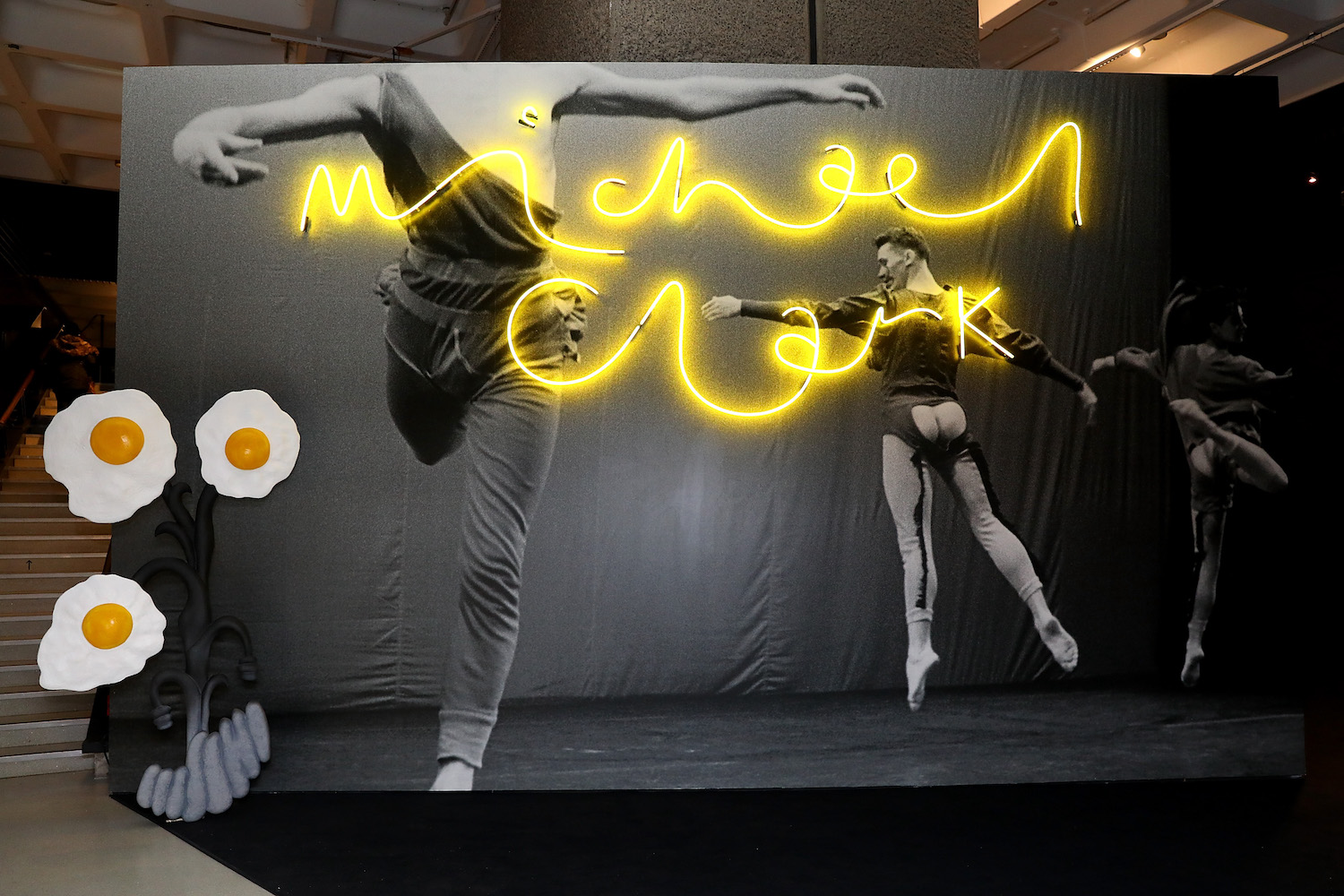

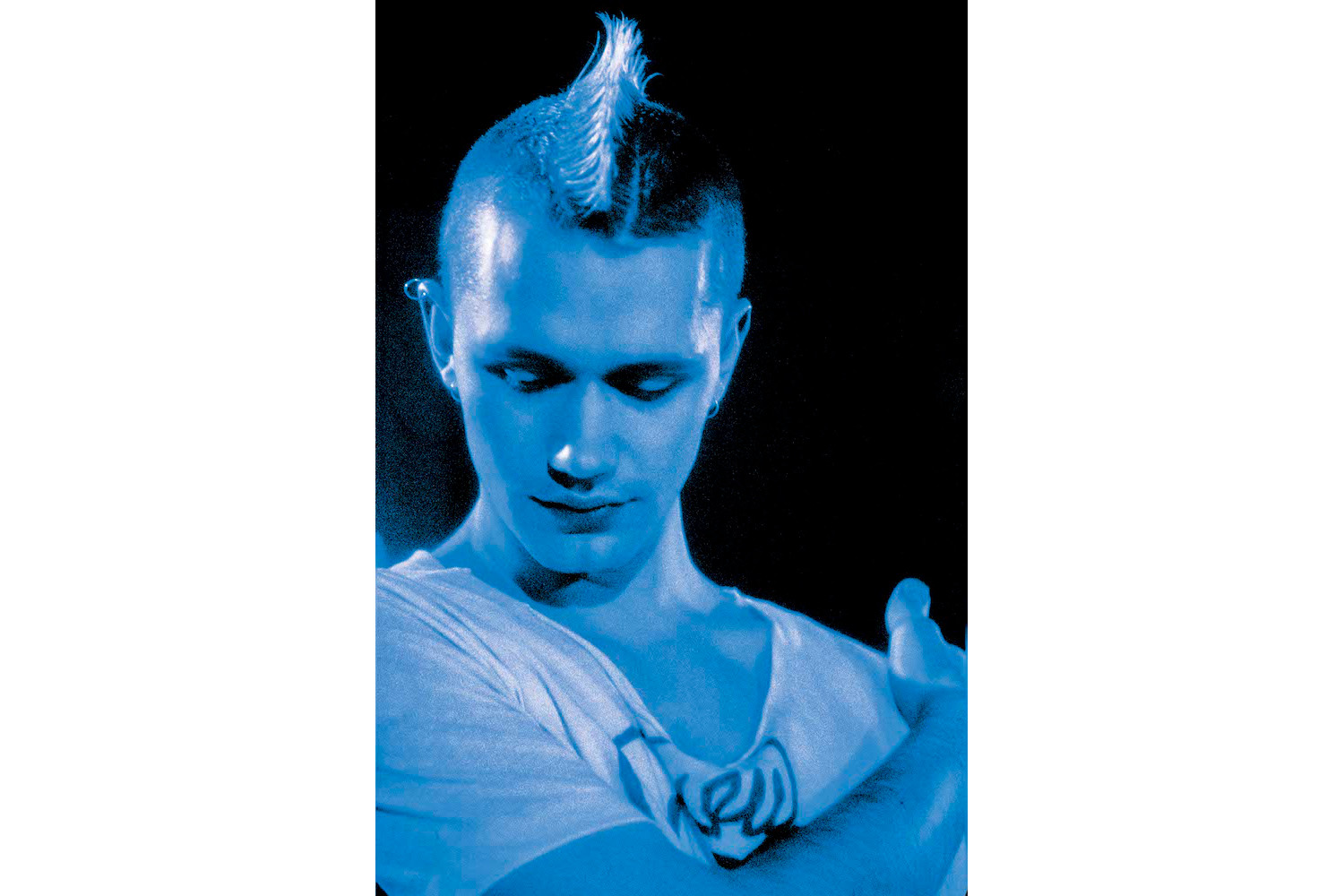

In 1984, for the closing minutes of The Fall’s performance on the BBC’s live TV music show The Old Grey Whistle Test, Mark E. Smith and his band deliver “Lay of the Land” alongside Michael Clark’s company of dancers. Here, Clark’s choreography orchestrates an anarchic construal of grace and giddiness, his fleeting finesse of line and arc disordered by collapsing postures and shuddery resistance. Like a cracked kaleidoscope continuing rotation, it is a patterning of bodies held in acute, albeit off-kilter, organization. Shapes and spins are worked in deliberate asynchrony. The troupe’s brief unity pulls focus to both the interdependency and singularity among performers, themselves berobed in tailored ways: pink rubber gloves, military caps, assless leotards. To climax, a pantomime horse enters the stage, which Clark appears to gag and then, to my mind, apply a powder puff.

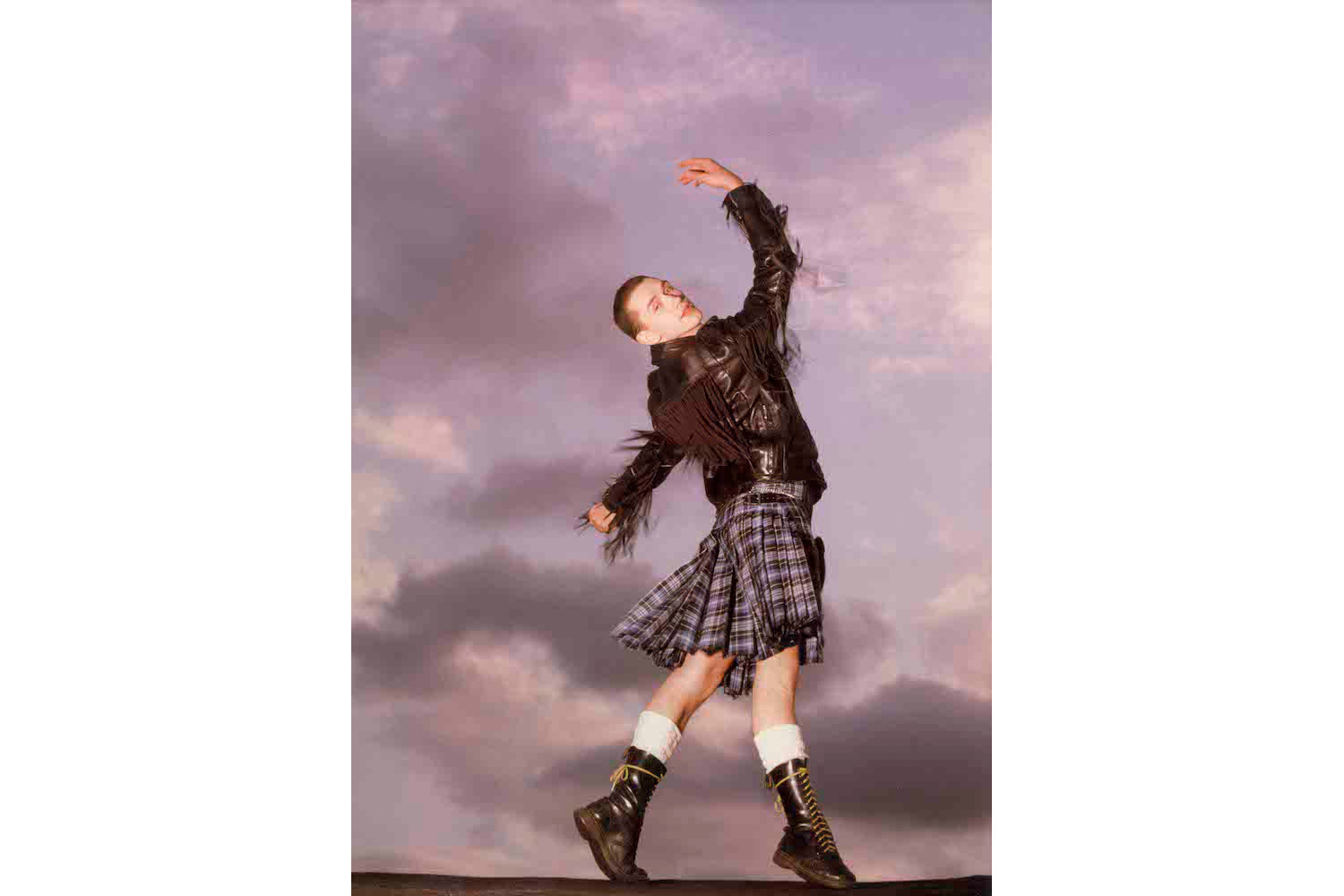

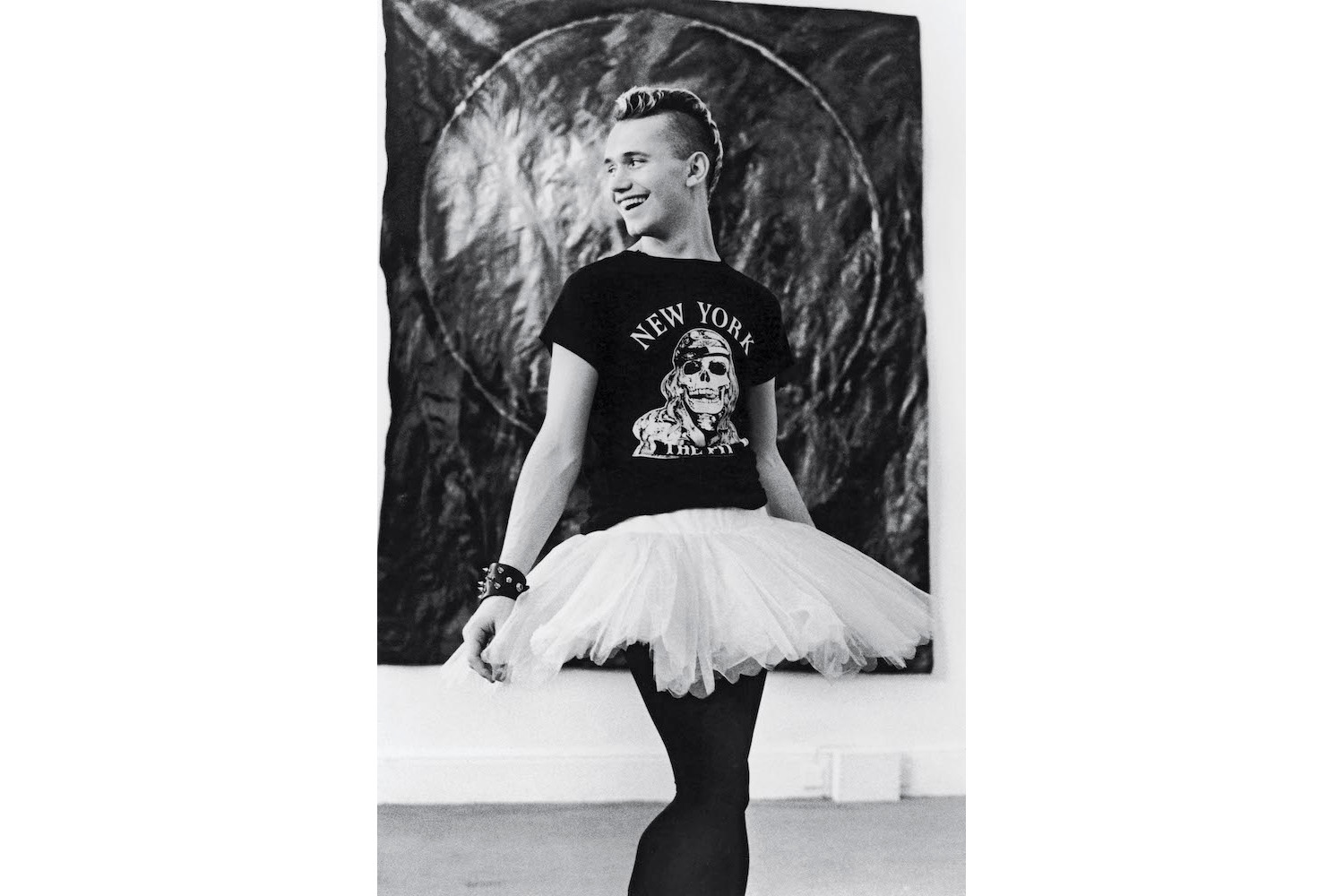

Such an intervention is illustrative of Clark’s then-nascent choreographic style, altogether jagged and orbital, crude and plushy, aslant and literal, queenly and graphic. In effect, the lyrical cushioned by camp and tempered by rigor, treated in a postmodernist palette. Clark’s practice extends centrifugally from the traditions of ballet, having trained from 1975 to 1979 at the Royal Ballet School in London, followed by practice at the Ballet Rambert. But this classicist discipline echoes an earlier training for Clark in his partaking of Scottish Highland dancing, from age four, in 1966. This tradition executed a form of sword dancing which soldiers would perform in preparation for battle, in turn creating a model substantiated by the fabric of social life. Here, dance shares in the constellatory forecast of ritual, as predicated by survival and succor, dance as safeguard, salve, solace. The Highland Fling, for instance, is alleged to have originated around 1790 when, as legend has it, “a shepherd boy on a hillside watched stags rearing and wheeling. The boy tried to copy the stag’s antics and hence we have the graceful curve of the hands and arms depicting the stag’s antlers.”1 This fable occasions dance as impulsive acknowledgement of self and surrounding, as projective worldview and introspective self-reflection. It is also symbolic of play’s twirl of observance and citation; the body becomes a site of differentiation in its very desire for mimicry.

Admiration from dance figures such as Frederick Ashton and Ninette de Valois extended to early generative friendships that would mature into enduring collaborations for Clark: Leigh Bowery and Trojan, whom he met at the Cha Cha Club under Charing Cross Station in 1980, and Cerith Wyn Evans, who visited Derek Jarman’s flat the same year. In 1981, Clark attended a summer school with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in New York, where he met John Cage and established friendships with Karole Armitage and Charles Atlas. He became well acquainted with the history of postmodernist practice in the US, such as the Judson Dance Theater and choreographers including Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer. Indeed, Rainer’s critique of Cage’s apolitical assumption of life as material for art via chance procedures, presuming life by default as already satisfactory, contrasts Clark’s entire oeuvre, which incorporates life forms he knows intimately — asymmetric, embellished, sharp, fruity. Of more lasting influence is Armitage, classically trained with George Balanchine, and who became absorbed in the downtown experimental scene, leading Clark to dance in her Drastic Classicism (1981) developed in collaboration with avant-garde composer and musician Rhys Chatham. Drastic Classicism’s clangorous ensemble of electric bass, guitars, and drums, along with downtown New York’s No Wave music experiments, provided critical links to the post-punk movement that proved influential for Clark.

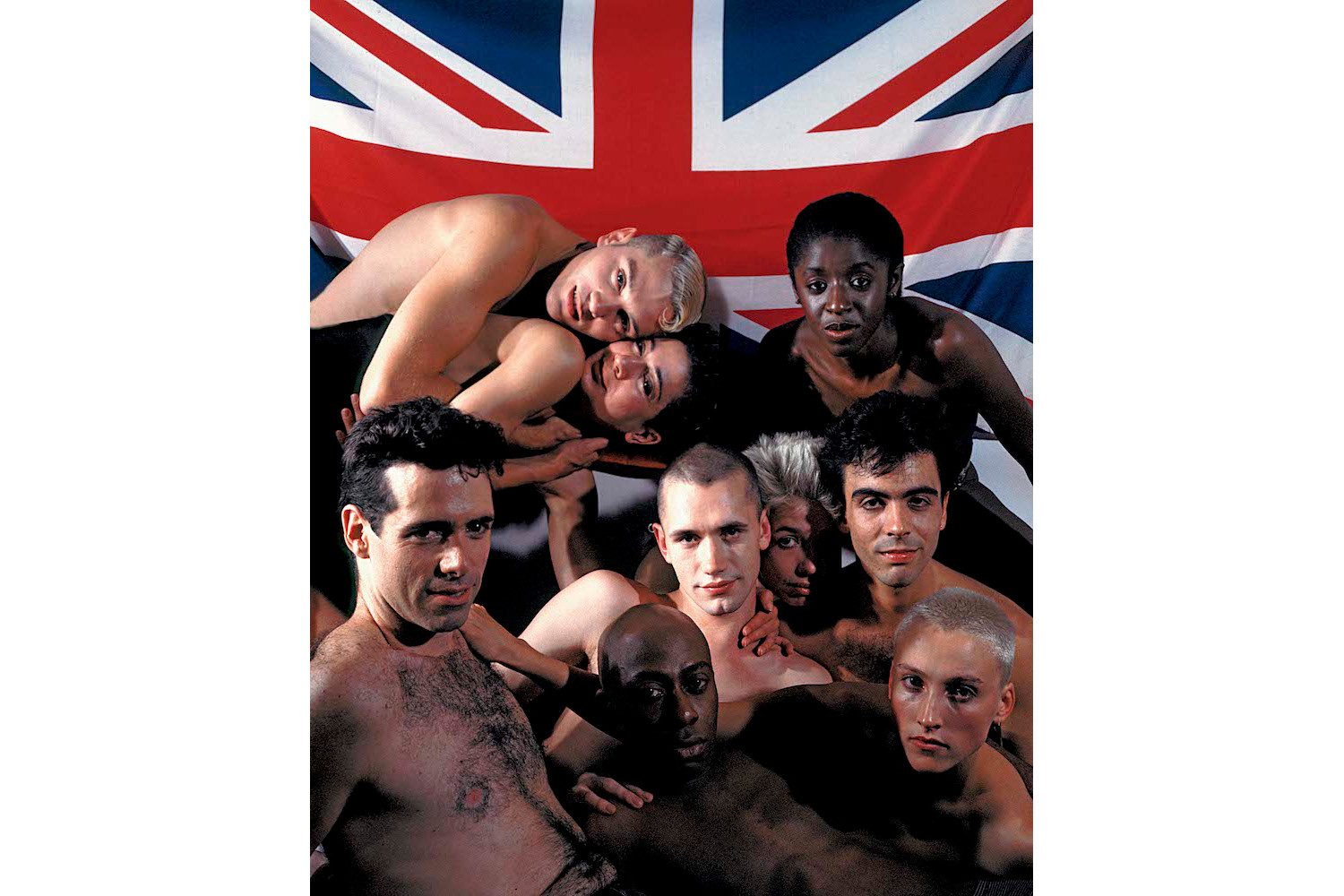

Crucially, Clark’s life-at-hand involves collaborators who embody the priding of invention and artifice as keystones of authenticity. This exaggeration was instructive in Atlas’s Hail the New Puritan (1986), a Channel-4 commissioned docu-fiction featuring a day in the life of Clark and his friends, in which each elaborated presentations of themselves. As a record, Atlas’s film glances to London’s discordant context from which the polyamory of Clark’s company emerged: militarized police against mass miners’ strikes; the punishing governance over the “homosexual body”; the brutalizing specter of AIDs; the intensification of Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberalism; the introduction of Section 28 — prohibiting the promotion of homosexuality (in its paradoxical characterization of gayness-as-contagion). That such queer subcultures were already underwritten encouraged an urgent reassessment and imagining of interdisciplinary tradition, bending preexisting disciplines and cultivating more joyous, articulate, and provocative practices in turn.

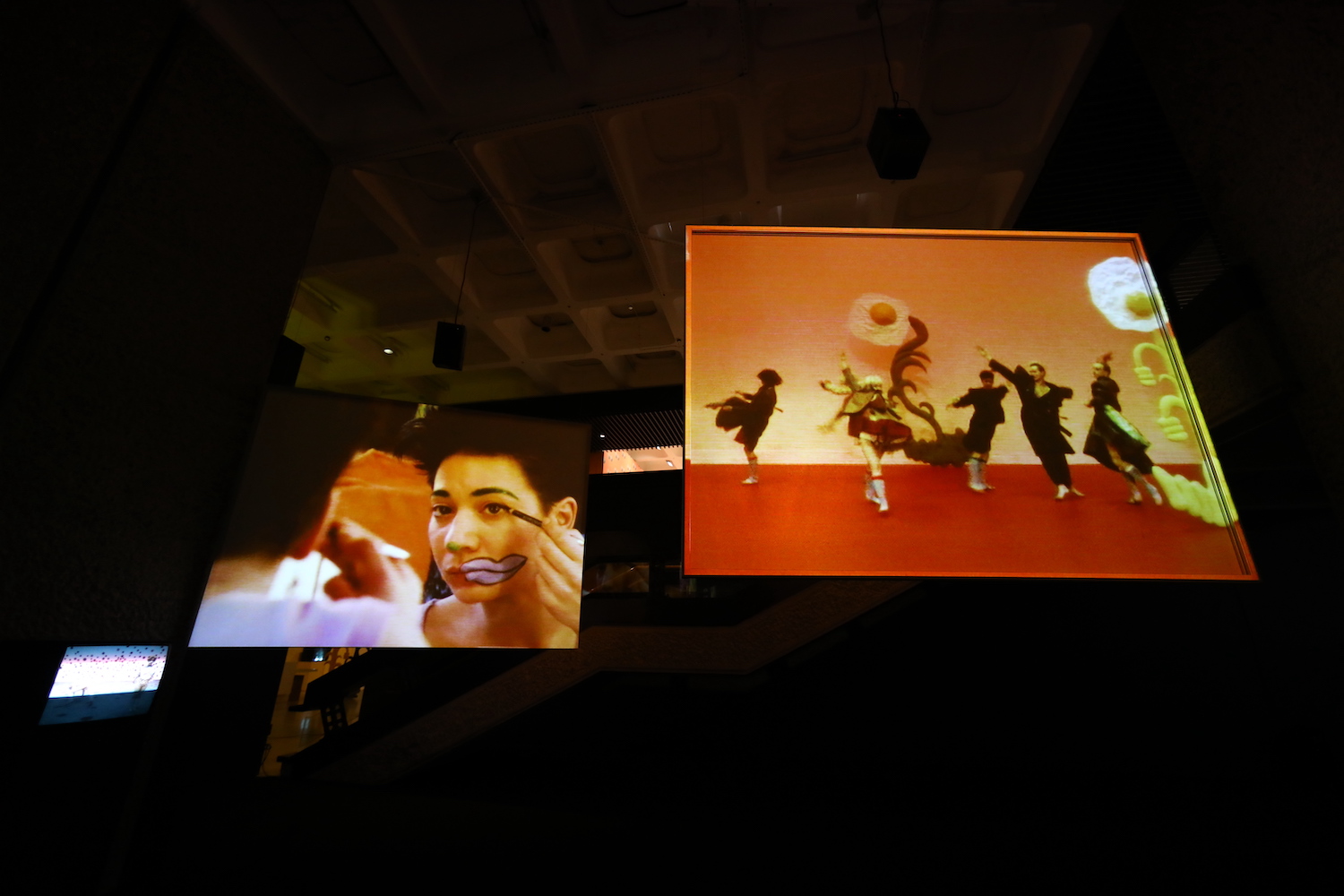

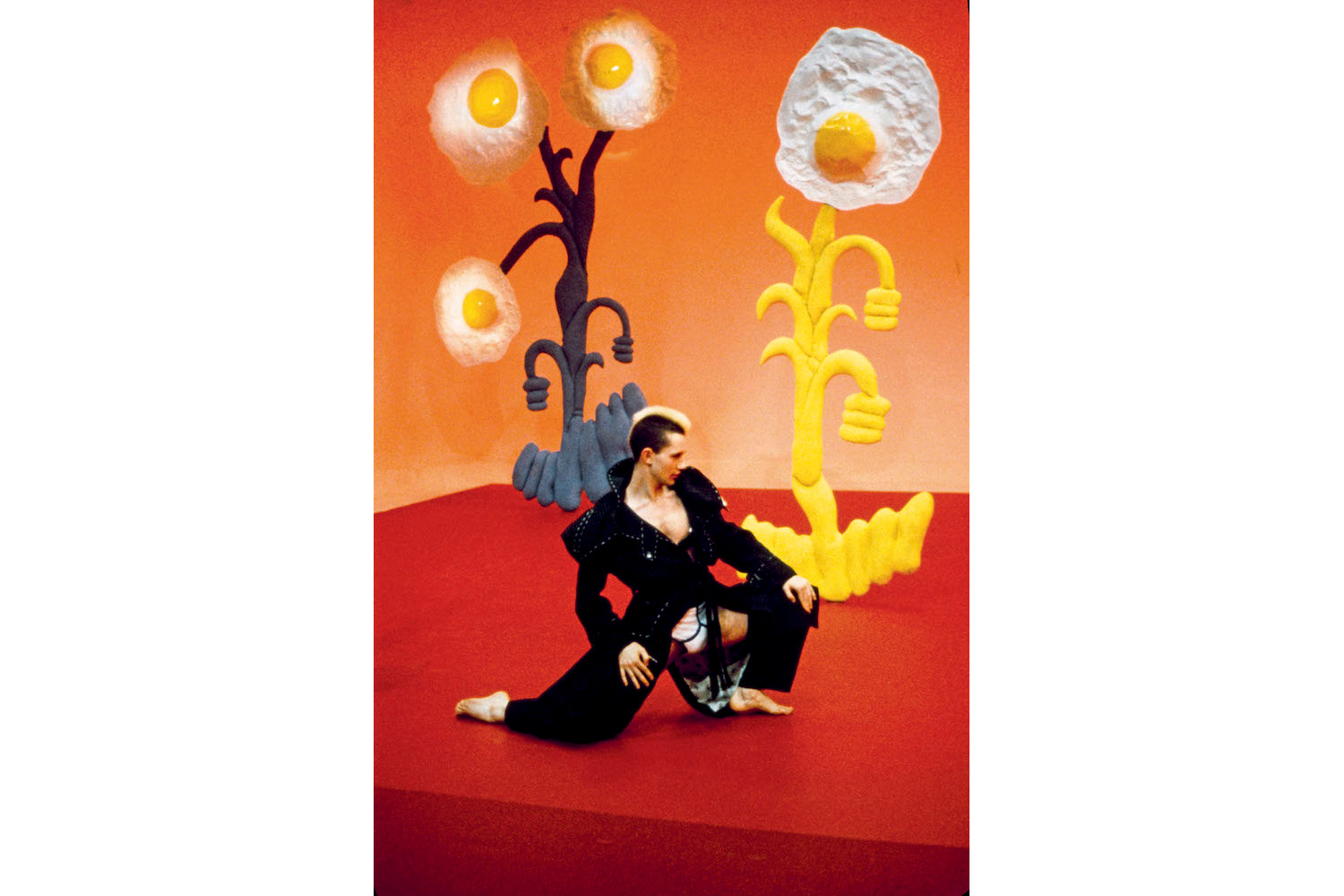

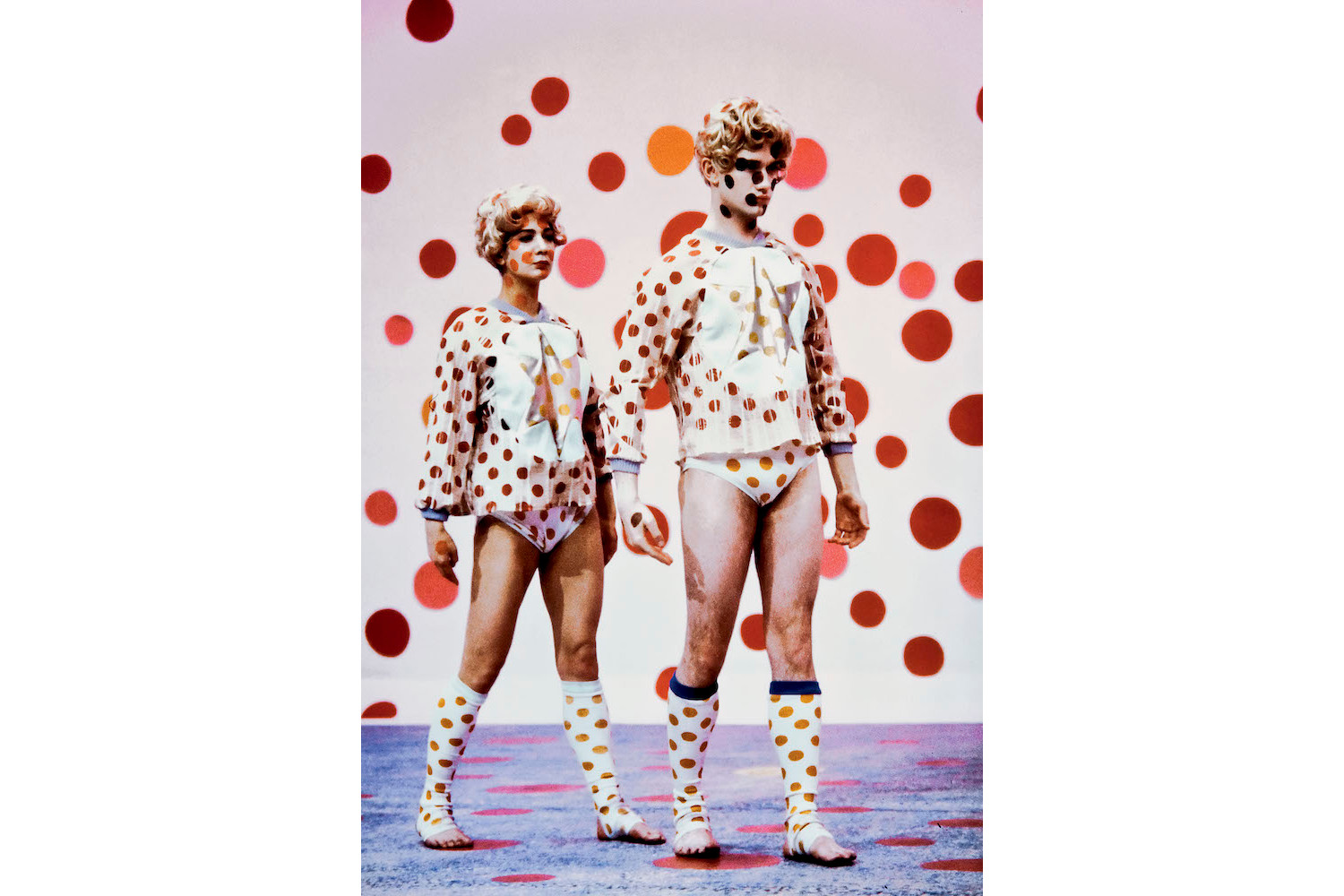

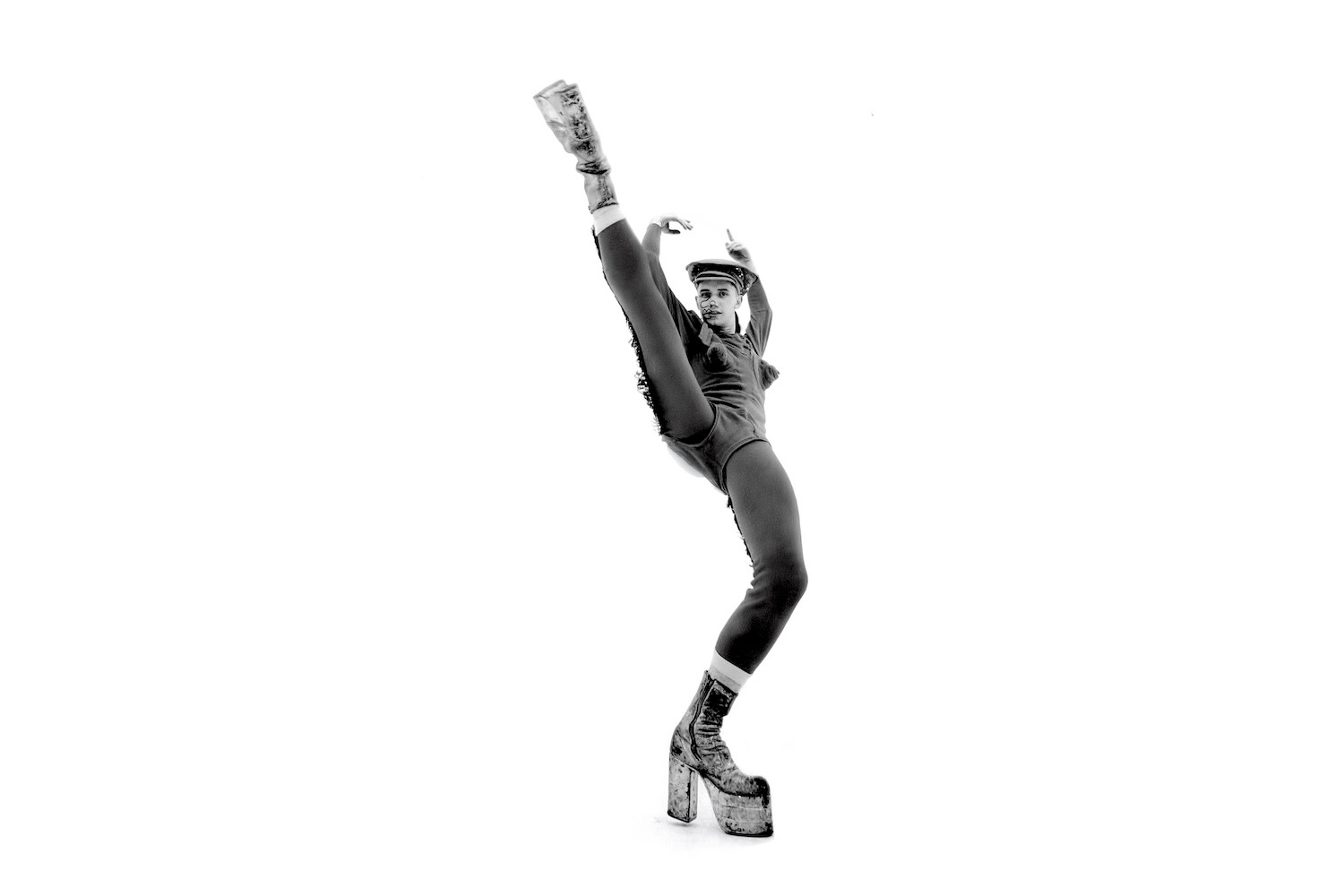

Hail the New Puritan achieved both critical glowering to these political strictures as well as pivotal vitalizing of Clark’s work as a dancer and choreographer. Opening scenes show “rehearsals” evidencing Clark’s slow-whirling style: fluid gyratory poises shot through with darting, scissoring angles and sudden realignments. Tailored too is the physical wit of his cumbersome vocabulary: the limping suggestion of lean and lilt, the torso contrapuntal and concave. Other recordings of performances to The Fall’s music prove essential footage of Clark and his dancers: they are heated by Technicolor flamboyance, donning melting harlequin make-up or painted polka dots as pluralizing potent marks. They execute a thrilling sequence in a sun-kissed-apricot-colored room, pillared by monumental fried-egg flowers and gargantuan overhanging Y-fronts — magnificent relics of Trojan’s painting Female Trouble (1984). Despite a ruinous political landscape, Atlas’s film is tenderly charged and amorous, marbled with narrative play and activity: a faux interview with Clark delivers on biography while ensuing moments capture Wyn Evans shooting a scene at the British Museum and Clark visiting friends Bowery, Trojan, and Rachel at Bowery’s Star Trek-wallpapered bedroom as multiple outfit changes occur. Clark ends up leading the dance floor in a random basement nightclub before heading to his bedroom, dancing to Elvis’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” in his underwear.

In leading the nightclub scene, Clark performs a sequence of hand gestures: a fascist salute, a cross sign, a money gesture soon dispensed in the cleavage, a beating heart, a peace sign reversed for insult. This inversion and decomposition of choreographic language allowed gesture to partake in the myriad movements of Clark’s style, paralleling the polysemy of words. It is also a means for morphosis, to perform the multi-tonal and polyvocal in one body, to shape-shift in gesture’s scintilla. This attention to language, structure, and musicality had been explored prior in works such as Dutiful Ducks (1982) — a companion piece to Charles Amirkhanian’s titular sound poem composed of staccato rhythms and syllabic clips punctuated by claps, stutters, and overlapping susurration. Of a feather, FLOCK (1982), Clark’s first independent work as a choreographer, chewed over the swan’s metaphoric potential, presenting Armitage in solo as The Dying Swan, the production accompanied by bird sounds and ornithological descriptions along with a projection by Wyn Evans of traveling clouds filmed by an aircraft’s animatronic lens.

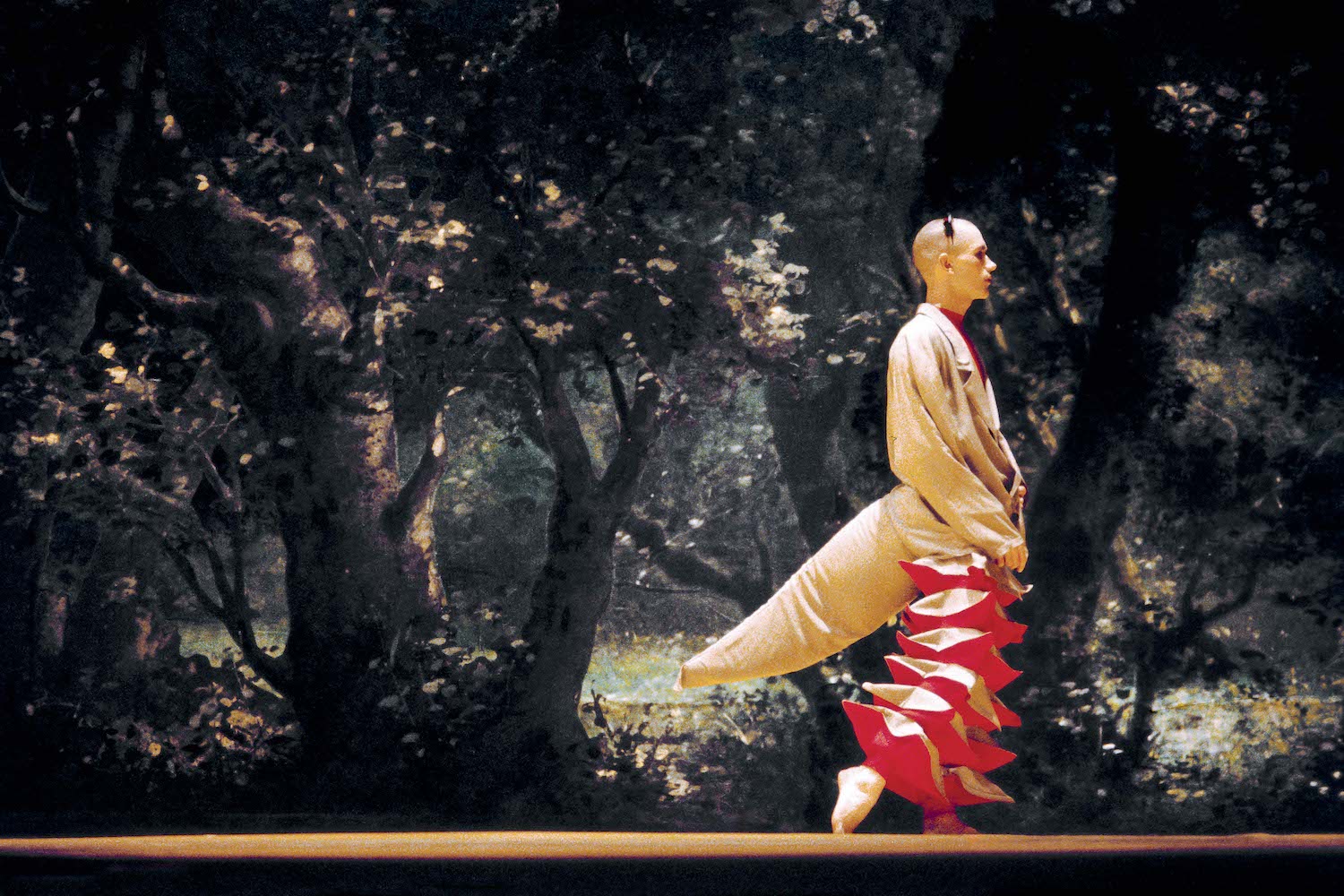

Atlas continued his collaboration with Clark in Because We Must (1989), another pseudo-documentary of more fantastical stylization. Principally based on Clark’s work staged at Sadler’s Wells, Atlas’s video segues from the stage, where Chopin preludes Bowery and Bryant performing Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder’s “Ebony and Ivory,” to the pub, where the bewigged, vermilion troupe perform a medley of Cockney classics. In another set, Clark performs a swift, jerking and leaping solo costumed in an oversized double-breast jacket complete with protruding dinosaur tail and stuffed concertina trousers, later accompanied by dancers sporting inflatable Stegosaurus headgear. As the dancers lollop and interlink a voiceover ponders the extinction of the dinosaurs, wondering if humans will also last for 140 million years. In other instances, a baroque frame lowers as a mirror to the glittering Bowery as though the subject were instituting their own vision. Melodious swinging choreography transgresses from trippy living room to stage in reflection of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913) as Clark plays variants of the maiden who dances herself to death in affirmation of new growth and fertility. Zany synths, bagpipes, neon leggings, spidery feather-trimmed capes: this revision made palpable Clark’s pop and New Romantic-inflected scenography loaded with connotations cherry-picked for the most sumptuous clash. Bowery’s crewel-embroidered bodices and pink sequined tights, finished with gimp mask and embellished crotch, were green-screened by Atlas to a backdrop of luminous limes and pinks turning floral fabric into funfair phantasm.

While indulgent and groovy, Atlas also intercut violent stroboscopic images in heady succession: fish, love hearts, mushrooms, irises, pot noodles, bestiality, steak, shit. Like the designed oscillation between comfort and obstruction in the costumes produced by BodyMap and Bowery, works such as Because We Must intensified the burgeoning saturation of media manipulation and commercialized graphics to generate a falsified reality.

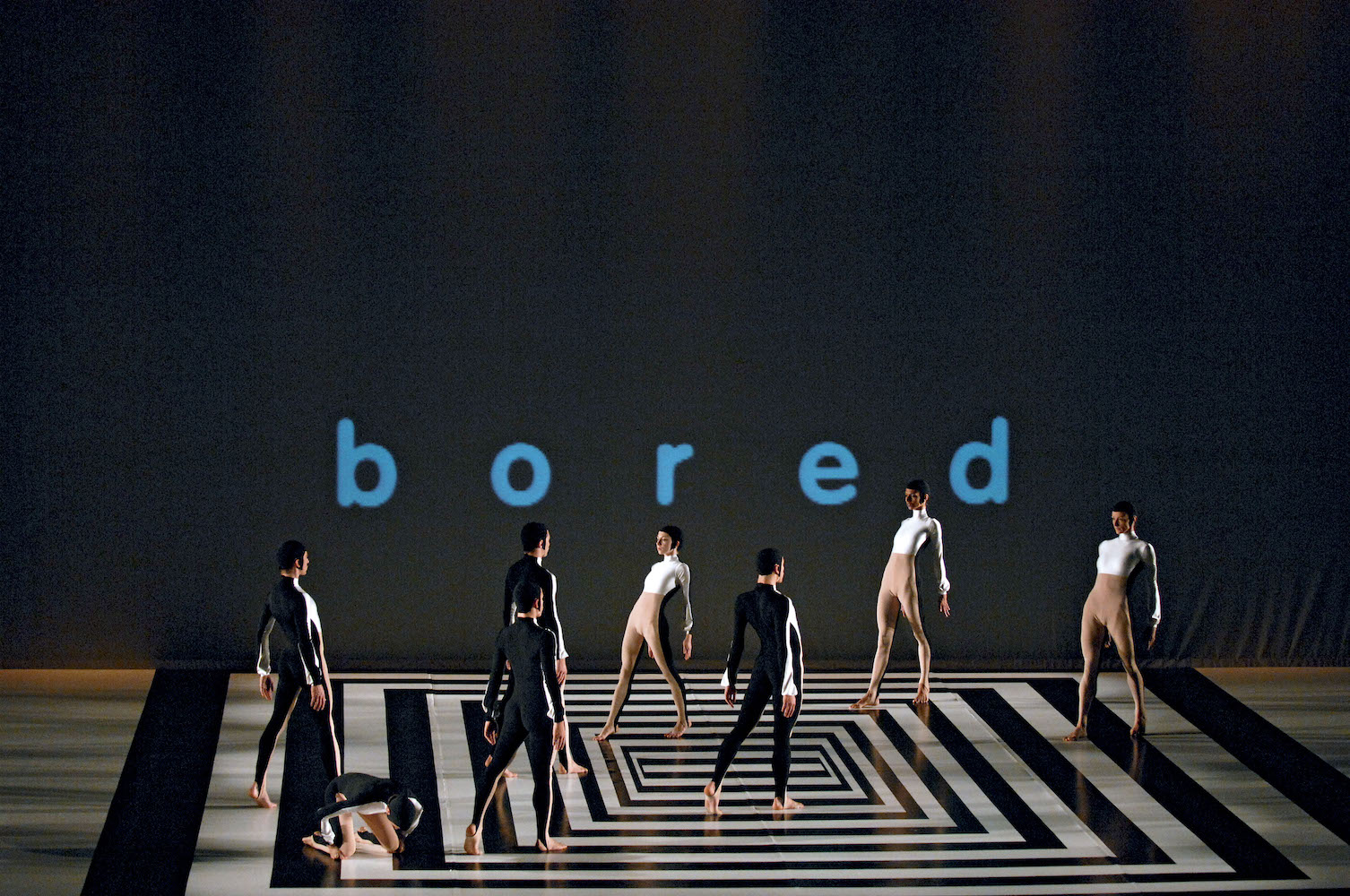

The dialectic of deconstruction and complicity in Clark’s integration of ballet discipline has created a foundation of (dis)continuity from which to exaggerate choreographic vocabulary previously instituted as irrelevant, flawed, or malformed. Such overidentification with ballet practice turns into a genuine act of subversion allowing Clark to perform several lives in dance — star, jester, prodigy — as well as interleave several styles: classicism, camp, rock, dada, punk. Throughout Clark’s work, stage, screen, apartment, nightclub, reality, fiction, rumor, and myth have coalesced and collided in a genuine queering of temporalities in which historic events reverberate into the present, constituting a repetition of patterns in parallel realities.

For instance, in I Am Curious, Orange (1988), Clark collaborated with The Fall in a commission for the Holland Festival to commemorate the tercentenary of William of Orange’s ascension to the English throne. As Mark E. Smith summarized: “The English get pissed off with their king, kick him out and get some Dutch bloke in.” Clark transferred the sectarian enmity between the Dutch Protestant William and Catholic King James II into a football game between Scottish Celtic and Rangers clubs. Elsewhere, Clark performed as Shakespearean human-ghoul hybrid Caliban, figuring as a seventeenth-century conception of “primitivism” in Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books (1991), a film adaptation of The Tempest. Sheathed in dirtied fleshy-pink body paint Clark writhes and stretches upon a rock in manners amphibious and demonic.

With undertones of pantomime and drag, Clark has performed society differently, contradicting normative principles of harmony and resurfacing drives in dance that were otherwise erased — namely, sexuality. That Clark’s raising of the blatant abundance of queer life occurred on stage leverages theater as a platform for critical acting out, a way to connect the present, be it self-affirming or self-annihilating, as well as a means to project a counter-future.

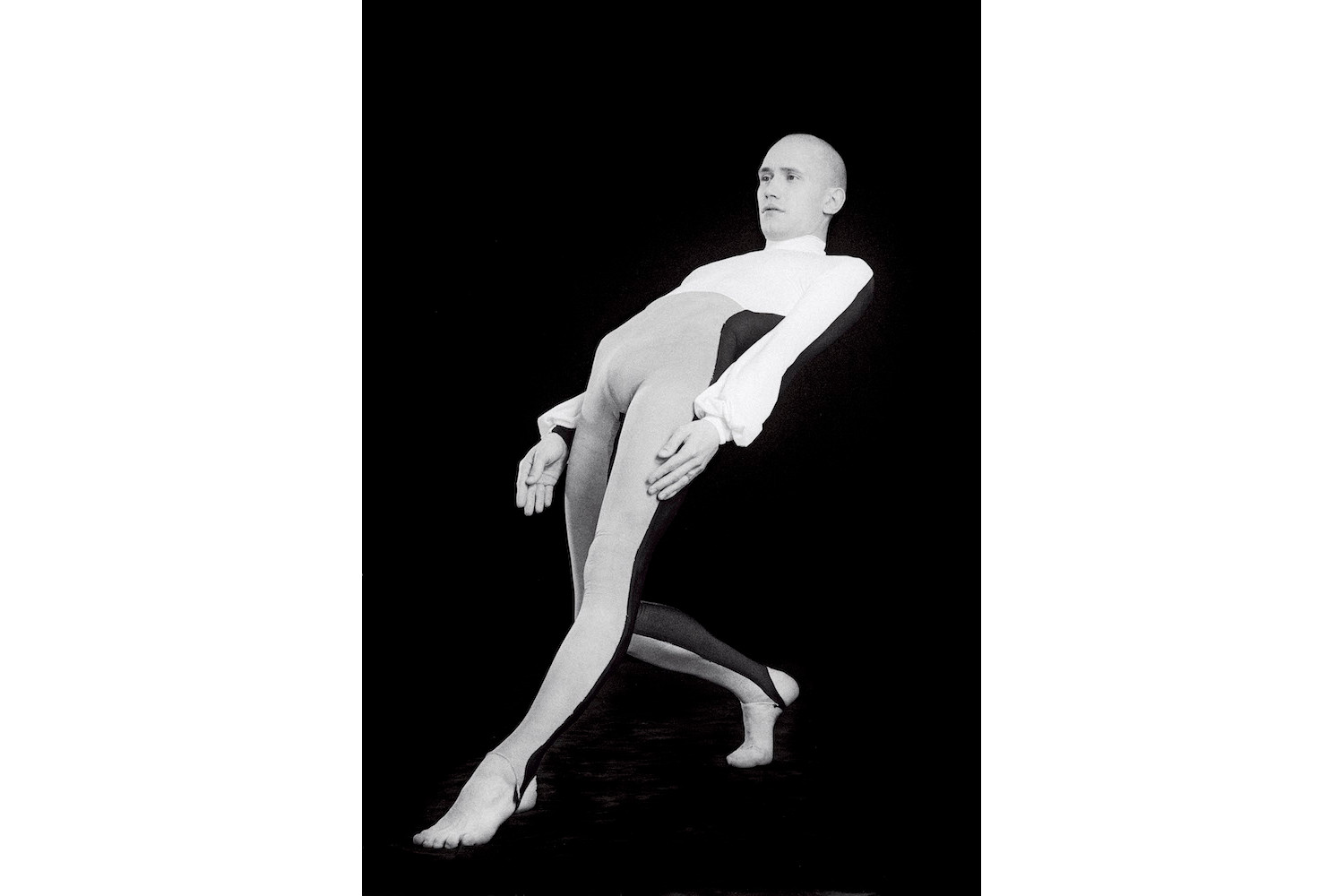

In the rond de jambe, the body often remains rigid while one foot outlines the circular limits of its reach across the floor, drafting a semi-circumference in space. In a port de bras the arms create a flowing periphery about the centralized body. For Clark’s solo Cosmic Dancer (1985), his arms also circle the body, rings evaporating and reforming with each rotation, the dancer becoming, as Clark says, “something like Saturn.” In a pixelated recording, Clark is clothed in licorice-black sleeves and slinky flares along with a satiny yellow tunic. He dips and spins, loosening and lacing concentric ovals as he turns to T Rex’s eponymous track, the lyrics gliding: “I danced myself out of the womb. Is it strange to dance so soon? I danced myself into the tomb.”