In the rearrangement of distance one finds a slippery continuum across Rachel Rose’s liminal and alchemical work. Distance, which determines the near and the far, extends its reach to shape behavior, border, territory, rationality; distance is also, as Rose says, “often tied to the gradation from aliveness to deadness.” To elasticize this gradation, Rose manipulates the spectrum of distance, challenging viewers to think about the qualities, tendencies, and sensations that might constitute “aliveness.”

Structured as a process of metamorphosis, Rose’s survey at Lafayette Anticipations denies the illusory logic of linear time. Rather, time in Rose’s eye turns foamy and clouded to effectively muse on the contingency of living and to problematize the human experience. We begin at pre-birth with a selection of glass and mineral sculptures spotlit upon black plinths: each Born (2019) lies between two materializations of time in one substance — sand. Rocks figured as fractured eggshell are coruscating and embrittled supports for treacly blown glass, their moment of contact immortalized. A limacine sliver of glass enters a glittering cavity as an eel might lick the ankle in a black river, slick and furtive; another hosts a bell jar dome whose rim has rumpled against the rock, frozen in the likeness of a jellyfish’s undulating crimp. Embryonic, geologic, and cosmic, each has its own beautifully opulent spook.

“You are made for the mutations you make.” This utterance of a thoroughly complex and material worldview ends the video work Sitting, Sleeping, Feeding (2013). Composed from found and original footage connecting zoological parks, a cryogenics laboratory, and a robotics perception laboratory, Rose establishes a liminal zone of existence she calls “deathfulness” or a death-like life wherein the context of being is so vacant and abstracted it becomes internalized. Here, we sense some of the blue-black emotional registers that dwell within Rose’s practice: depression, boredom, and the nacreous specter of loneliness. Sitting, Sleeping, Feeding works through those possible glowering moods, as opposed to merely translating them, with an acerbic and sterile audio-visual collage. A polar bear appears numb to surrounding snowfall; a panda’s shattering of bamboo cracks loudly, too closely; sea slugs, skateboarding, a pink mug, a labradoodle, crushed blueberries, a strobing peacock — these make for splintering, painterly, and piercing moments of notice. The fraught politics of dependency evidently appears at stake in this desire for a sheer perpetuation of life, even if the results are immobile, violently abstracted, or cadaverous.

The choreography of sound, footage, color, and texture in Sitting, Sleeping, Feeding allows the work to involve embodiment, critical perception, and dreamscape; it is a fitting introduction to Lake Valley (2016), which alludes to the dawning of adulthood and the construction of the child as a moral barometer and linguistic construct. Here, Rose begins to unfurl the petallike quality of story as a technique to revise the conditioning of rationality. Lake Valley is composed of thousands of nineteenth- and twentieth-century children’s book illustrations collaged and animated with cel drawings, presenting the story of a house pet that outsteps the comfort of its domestic borders. The conventional absence and abandonment that pervades such stories is realized in Lake Valley with formal irruption and material abundance: overlapping pools; tufts of grass; petals as papery aggregates; even a cracked egg releases a lavic flood of drunken patterns. Despite this, the dematerialized, suspended state of dreaming are the moments of Rose’s true experimentation. A girl hovers in the ultramarine air of her bedroom, with visions of recurring red alpines that shudder and stretch like crocodile skin — it is washed out by morning, like the stark transition: you’re an adult now.

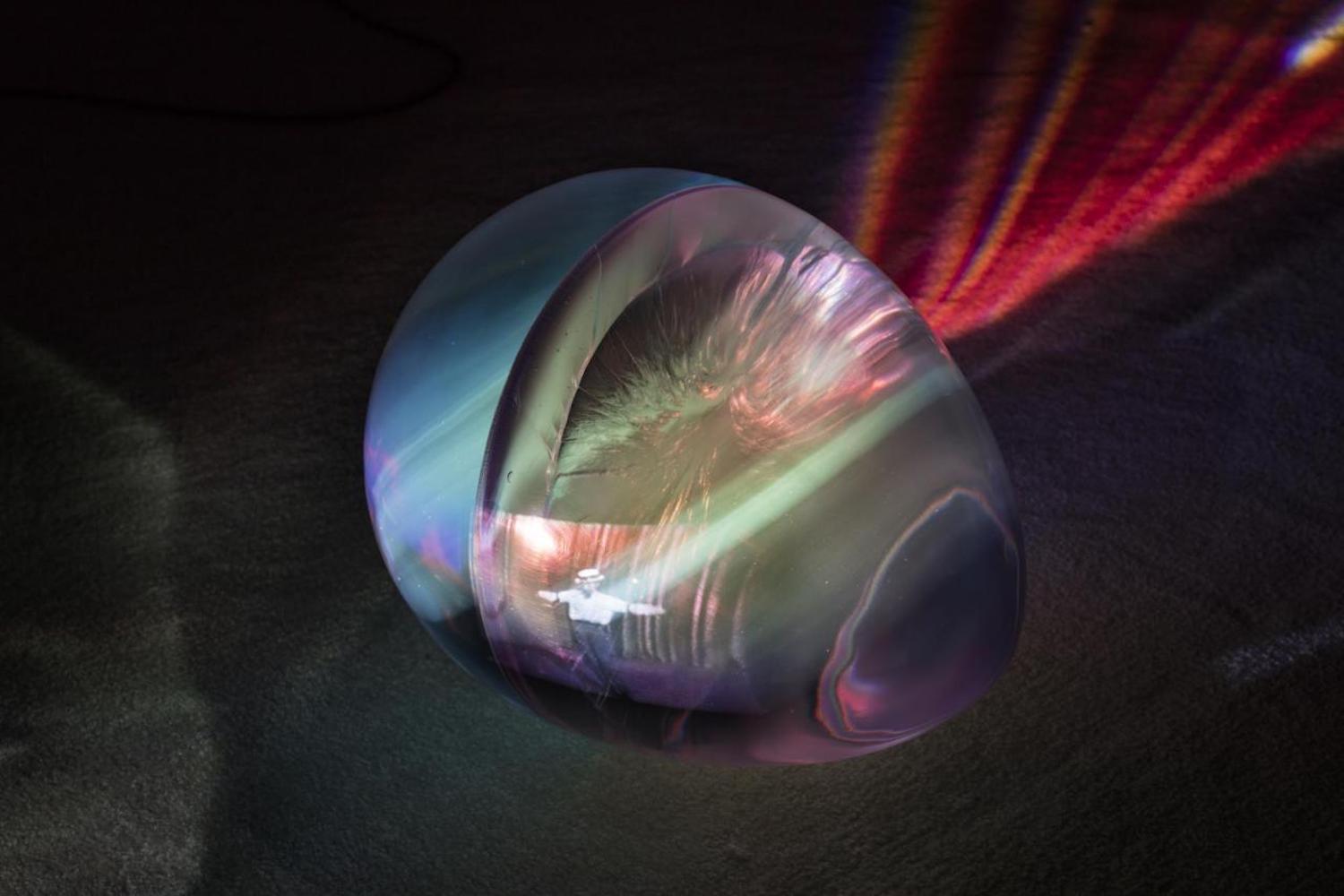

Upstairs, Wil-o-Wisp (2018) tells a narrative of the fictional Elspeth Blake, a mystic and healer, through three decades of change in seventeenth-century agrarian England. Rose connects the process of deforestation and the privatization of land as mobilized by rationalism, displacing women such as Blake and mutating the conceptualization of magic, mysticism, and embodied knowledge. At intervals of her story, Elspeth is seen foraging in front of the screen depicting her tale; the alignment of story and spatiality comes into view: stories not only as formal vessels for meaning but as networks which sustain selfhood, stories as constructs for worldviews whether fleeting or legendary, reflective or projecting, near or far. Curiously, Rose includes an excerpt from Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) patterned in moiré, whose voluminous moon, insectile fairies, and whirring forestry unify in fumy vapors only for the fairies to unscramble as one corkscrewing stream. Both works utilize rear projection as a means to generate surreal depth, but Rose goes further, placing three cured water and glass sculptures (made from the same production as lenses from the seventeenth century) in front of the screen. These standing eggs encourage a metafictive encounter, magnifying and falsifying the video’s materiality in a refusal of crystallinity-as-clarity. Torsion and haze suggest lenses of different insight.

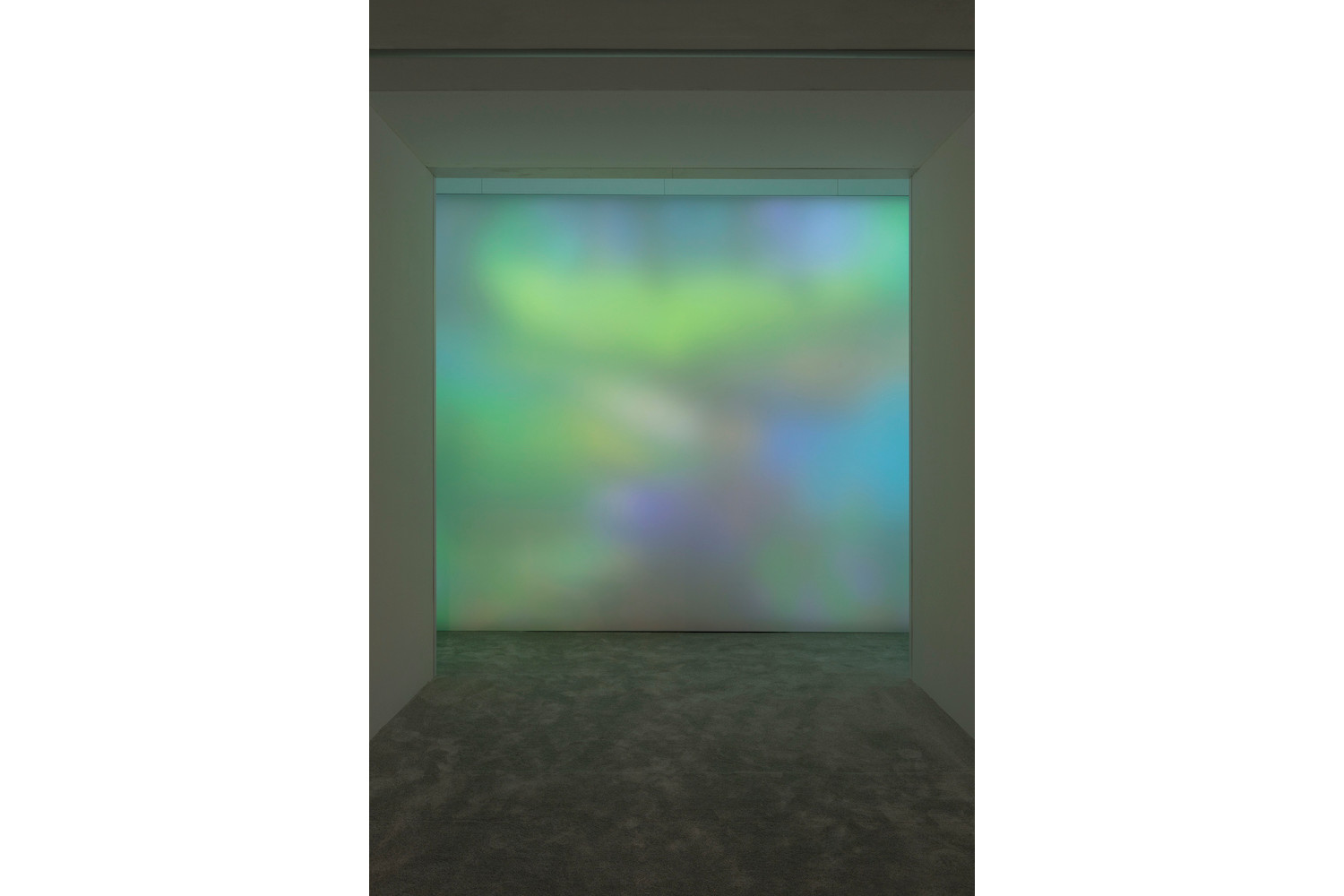

Installed at the uppermost region of the building, Everything and More (2015) is a fitting terminus, as it meditates on humanity’s experience of infinity, euphoria, and transcendence. The work blends an interview with astronaut David Wolf detailing his space walk while on the Mir Space Station, and his return to Earth; the residual vocals of Aretha Franklin; emulsifications of oil, milk, and ink; and blissed-out concertgoers. It shifts from expanse and embodiment; the marbling of granularity and cosmology; ambience sugared by Franklin; narrative formalized by Wolf; celestial bodies and corporeal bodies. Temporal pooling: depth, dissolution, intimacy, extremity, Rose’s profound control of distance and distances unpeels the unimagined possibilities of perception and of possibility itself. I leave, alone, thinking on this very more.