Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

The film opens on a beach in Toubab Dialaw, Senegal. There is a carefully raked rectangle of sand with dancers waiting on either side. “Normally this is behind the curtain,” says the rehearsal director, addressing the dancers through a microphone, “and we are not supposed to see you.”

Dancing at Dusk — A Moment with Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring is the final rehearsal for The Rite of Spring / common ground[s], filmed days before its world premiere in Dakar. Formed of thirty-eight dancers from fourteen African countries, École des Sables was due to tour the piece in Wuppertal, London, Paris, and Amsterdam before coronavirus lockdown forced international borders to close and the company to disband. Dancing at Dusk captures the company’s last meeting, the rectangle of sand their stage. Over July the film is available to rent on Sadler’s Wells Theatre’s Digital Stage for £5, presenting viewers with the rare opportunity to witness a rehearsal in its entirety. But while the chance to peek behind the virtual curtain offers an enticing substitute, can the simulated experience outweigh the absence of the live performance?

At thirty-nine minutes, director Florian Heinzen-Ziob navigates our remoteness via the luxury of an objectively good view. The camera pans in and out of the action, following the dancers who lead the narrative, choreographed around the exchange of a single red dress. Close-ups reveal the texture of skin, grains of sand caught in hair, bodies bathed in twilight. We gain the kind of perspective only those with front row seats could ever come close to. Yet when the camera pulls away there is inevitably a sense of loss — one that reiterates the distance between us, the reality of our screens, and the stark reminder that our gaze is being directed.

The “digital stage” may threaten our agency to follow the dance with our own eyes, but not all is lost. If part of the pleasure of watching dance is vicarious, then witnessing a dancer move across the sunbathed sand at dusk is a form of escapism many in lockdown would long for. The 173 comments reacting to the trailer on Sadler’s Wells’ Instagram attest to this. Among these, the word “beautiful” appears fourteen times; there are 3 “phenomenal”s, 3 “amazing”s, 2 “stunning”s, and 1 “breathtaking.” For the most part these comments focus on the spectacle and how it appeals to our visual or aesthetic sensibilities. When it comes to dance theater, however, post-show language often incorporates the whole body. We are moved by the dance. It can be spine-tingling. It often touches us. Has commenting online come to replace post-show chatter, then, or are people simply reacting to the trailer? “Chills! The most incredible feeling. I can’t wait to watch!!” one commenter writes. “Wish I had a bigger screen!” writes another.

No screen could be big enough to fit the dimensions of the stage (in this case, the beach), and it is precisely this loss of dimensionality that we must mediate. To some extent, we’re used to this. The cinema trained us early on to suspend our disbelief, joined a few decades later by our TV screens and laptops. Though remote, the digital stage has the potential to offer a multisensory appeal. “I had tears in my eyes and goosebumps on my arms,” writes one commenter. At the loss of the physical, shared space of the theater, we establish our positions as viewers in relation to the bodies on screen. Inviting them into our most intimate spaces (our living rooms, our bedrooms), our screens forge such haptic possibilities via a mode of viewing that incorporates both the tactile and the visual. “In haptic visuality the eyes themselves function like organs of touch,” writes Laura U. Marks in The Skin of the Film. It’s an embodied mode of viewing that attempts to bridge the gap.

While “the digital stage” may be a relatively new concept, dance film dates back to the nineteenth century. Loie Fuller was a pioneer of the genre with her Serpentine Dance, captured by the Lumière brothers in 1896. Further examples include Oskar Schlemmer’s Das Triadische Ballett (The Triadic Ballet, 1921), Maya Deren’s films of the 1940s and ’50s, and Chantal Akerman’s Un jour Pina a demandé (One Day Pina Asked, 1983), in which the mediums of dance and film are fused so well they are mutually defined. Bausch herself directed one feature-length film in 1990. Die Klage der Kaiserin (The Complaint of an Empress) traces the turning of the four seasons as dancers move across various landscapes battling the elements. Similarly, the incidental factors in Dancing at Dusk — the wind, the fading light, the donkey and cart in the background, the crew in the opening and closing shots — become integral to the film’s feeling of “liveness.”

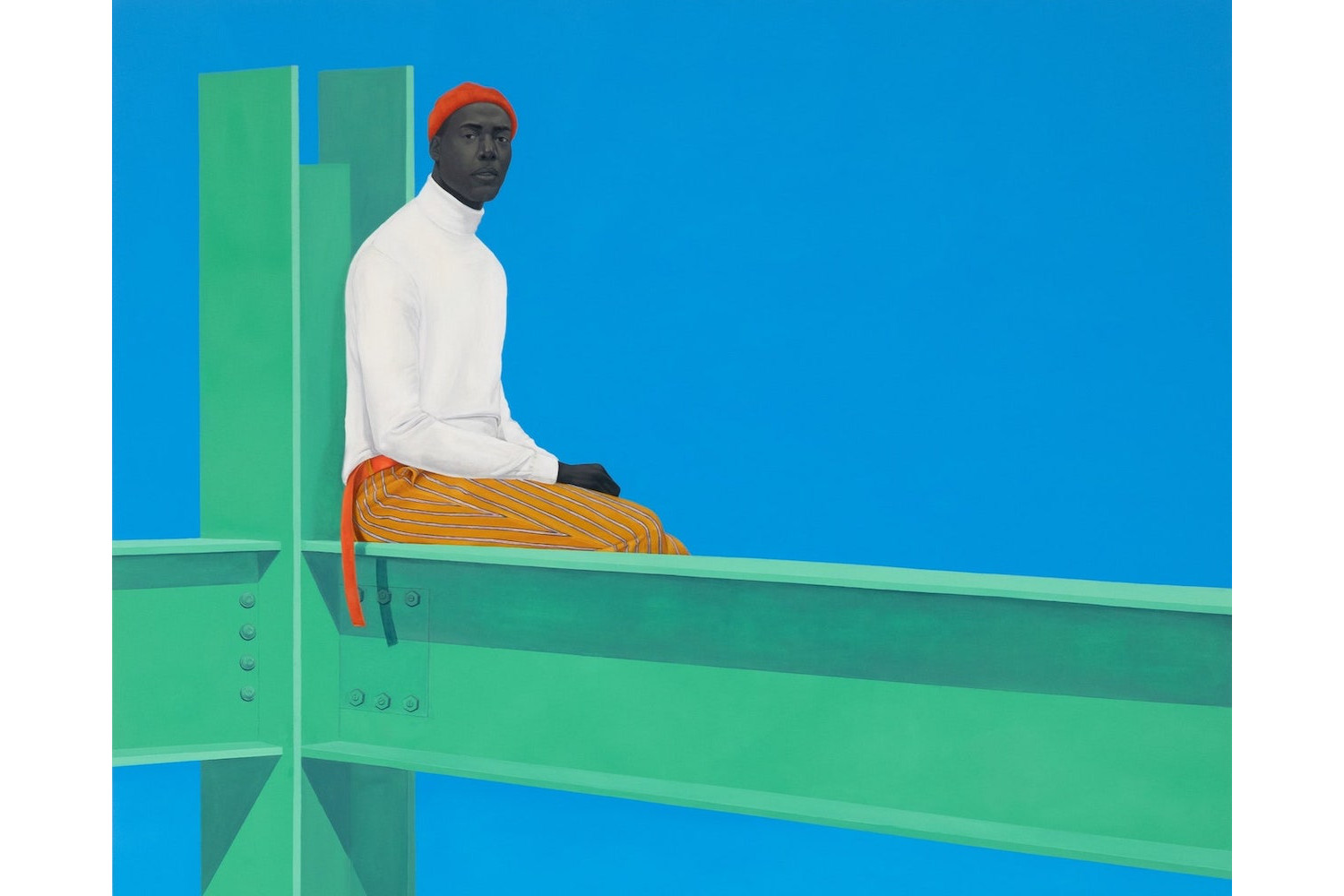

Though it is framed as a rehearsal, Dancing at Dusk embodies the feeling of a final accomplished piece. The beach setting is so far removed from any common notion of a rehearsal space that it starts to resemble an elaborate set. Children can be spotted playing on the horizon. A sea breeze forces fabric to cling to dancers’ bodies. The wind, in particular, plays a central role in the film, as dancers lean into it with their dresses expanding like sails. These dresses — sheer, “skin-colored” tunics that replicate those worn by the original company in 1975 — today match the color of the sand more so than the brown bodies that wear them. With Pina Bausch, there will always be the question of her legacy and how it is being upheld, and The Rite of Spring / common ground[s] marks a progressive step in the Foundation’s repertoire. In the context of 2020, however, these costumes point to an uncomfortable history of dance in which black and brown bodies were largely excluded.

When placed within a historical context, Dancing at Dusk becomes all the more powerful. The film was shot just across the water from Dakar, the nearest point on the continent to the Americas. Off the coast lies Gorée Island, home to Maison des Esclaves (House of Slaves) and its Door of No Return — a museum and memorial to the Atlantic slave trade. For hundreds of years, this area represented the final exit point of slaves from Africa. As dancers move to the urgent chords of Stravinsky, the geohistorical significance of the moment drifts in with the sea breeze. The original set, designed by Rolf Borzik, included a stage covered in a thick layer of peat, intended to make the dancers move harder. Swapping earth for sand, the dancers of École des Sables dance as if their lives depend on it. Movements are repeated over and over. The action of hands held in a single fist — beating chests, slapping thighs — is a central motif, one that recurs again and again within the choreography. In light of the current moment, the clenched fist carries an added symbolic weight — used by the Black Lives Matter movement to represent black liberation and solidarity. As contemporary audiences of Dancing at Dusk ascribe new meaning to Bausch’s seminal work, we can begin to ask ourselves: What does The Rite of Spring have to say in the socially distanced, politically activated summer of 2020?

When the stage becomes digital, it automatically becomes global. This invites a wider demographic, including those who may not have access to a theater, those who cannot afford a full-price ticket, and those who have never watched a piece of dance theater before. This widening of the audience nonetheless comes at a cost. Casting its communal gaze, Dancing at Dusk removes the democratic viewing experience of the theater or live performance space. We are, after all, watching the dance through the director’s lens. So while the luxury of a close-up lends the viewer an objectively good view, it also highlights our lack of agency and likewise our remoteness from the bodies on screen.

The digital stage facilitates an absence of other bodies, too — those belonging to the audience, peripheral beings whose physical presence aids the experience of a live performance and the notion of collective viewing. With many venues moving online in recent months, we can start to wonder what the post-pandemic world of live performance might look like. Through necessity, many venues now own the tools and knowhow to record and livestream. Whether or not they will continue to make use of these, when it is safe to reopen, is a consideration that will shape the way we interact with live performance in the future. If venues can offer both a local and a digital stage — and likewise multiply ticket sales — are they likely not to? On the digital stage, every seat is the best in the house. If only we could get a ticket to the beach.