It is hard for anything to stand out at LISTE. This is at least in part due to how the booths are placed around the building, branching off a series of cramped, rusty staircases. Unless, that is, you are looking for something specific. There were two exceptions this year. One was the sheer number of works sharing ‘apocalyptic’ themes. The other discernible trend was paintings that question the meaning of what painting still is or could be in the future. This was to be found in one room in particular.

Apocalypse is hardly a new artistic theme. Centuries ago, artists dealt with Christian eschatology and the story of the last judgment at the end of historical time. The last few generations asked whether humanity would destroy itself in a nuclear holocaust. It is rare, however, for artists as young as Guan Xiao (Antenna Space, Shanghai), Agata Ingarden (Piktogram, Warsaw), Sebastian Jefford (Gianni Manhattan, Vienna), and Isaac Lythgoe (Super Dakota, Brussels), all works 2019, to bear the emotional burden of the extinction of all life on earth. Their catastrophic imagery does not cross over entirely with the painting trend, but Jefford’s work provides a link between them.

In addition to Patrick Goddard’s wild reflections on the political chaos of the present (at Seventeen, London) and Klára Hosnedlová’s touchingly introspective portraits (at hunt kastner, Prague), LISTE had a standout individual room questioning the stakes of painting as such. This unified booths from Bodega (New York), Gianni Manhattan (Vienna), Union Pacific (London), and Weiss Falk (Basel), tucked at the end of a second-floor corridor, which otherwise displayed works with very different feels and styles. Sebastian Jefford’s works at Gianni Manhattan are what he calls ‘sculptures of images.’ They have a foot in both camps as a result, using apocalyptic imagery without abandoning the medium of painting. To make sense of this, we need to deal with each theme in turn.

The worries expressed in the work of Goddard, Guan, Ingarden, Jefford, and Lythgoe suggest that philosopher Fredric Jameson’s ‘nostalgia mode’ has been replaced by what we might call the ‘new apocalyptic mode.’ Jameson thought that ‘retro’ effects are built into postmodern culture. This makes, for example, period films using stylistic effects from the time in which they are set look ‘out of time.’ Cultural theorist Mark Fisher, meanwhile, thought ‘formal nostalgia’ stopped us from thinking or making anything truly new.

The ‘new apocalyptic mode,’ however, is when the Sex Pistols’ alienated cry of “no future” is an accurate prediction of what will happen if we don’t change things soon. Melting icecaps and boiling seas are no longer just scenes from high-budget disaster movies. It may be that all the achievements of human civilization will be rendered meaningless within our own lifetimes.

Guan Xiao’s Pond, for example, a crooked elm tree molded in ghoulish, shiny, pigmented brass, shows up the poverty of the collective imagination in the face of climate change. The powerful cannot think or act quickly enough to stop us from destroying the planet; no image of the damage we’ve done so far is shocking enough to make us act together.

Where Guan shows us how we have defiled nature, Agata Ingarden shows nature’s revenge on us. The bulbous, dangling mass of Solstice (Bomba Fragola) is like a fossil from the ruined future, dangling from something resembling a basketball net. We are but mortal beings obsessed with our own legacies. Solstice, however, visualizes the doom of not just our own personal ambitions, but of everything people have done to make the world a habitable place, from grand architectural projects to disposable consumer goods.

Still, there are long black nights ahead before we get to that point. Last Light and Candle Light by Isaac Lythgoe look like makeshift lanterns warding off the unknown, but they offer little comfort. In both, the jaws of a wax dragon clamp onto a jar containing tiny doll-like figurines floating in a black-green ooze, like human bodies that will one day turn to fossil fuels after millions of years of undisturbed pressure.

The numbers painted on Sebastian Jefford’s Sleep Furiously and Evening Colours show how many days have elapsed between 0AD and the day he started making the work. They function like a doomsday clock in reverse, showing the futility of all we are and all we do when disaster is surely ahead. Sleep Furiously juxtaposes the green skull and crossbones from biohazard warnings with two pets sleeping nearby, unaware of the calamity to come. In Evening Colours a fish gasps for water in the shadow of a barren tree set against a fiery red sky, once death is already everywhere.

These ‘sculptures of images’ are not quite paintings. They look like used globules of chewing gum resurrected to teach us a lesson about ecological collapse. Yet they are hung from the wall, so at the very least they make reference to painting even if it is only by negation. In that sense, they share a theme with the other works on view here by Yoan Mudry (Union Pacific), Matthis Gasser (Weiss Falk), and Orion Martin (Bodega). The room ultimately feels like a white cube exhibition crash-landing inside LISTE.

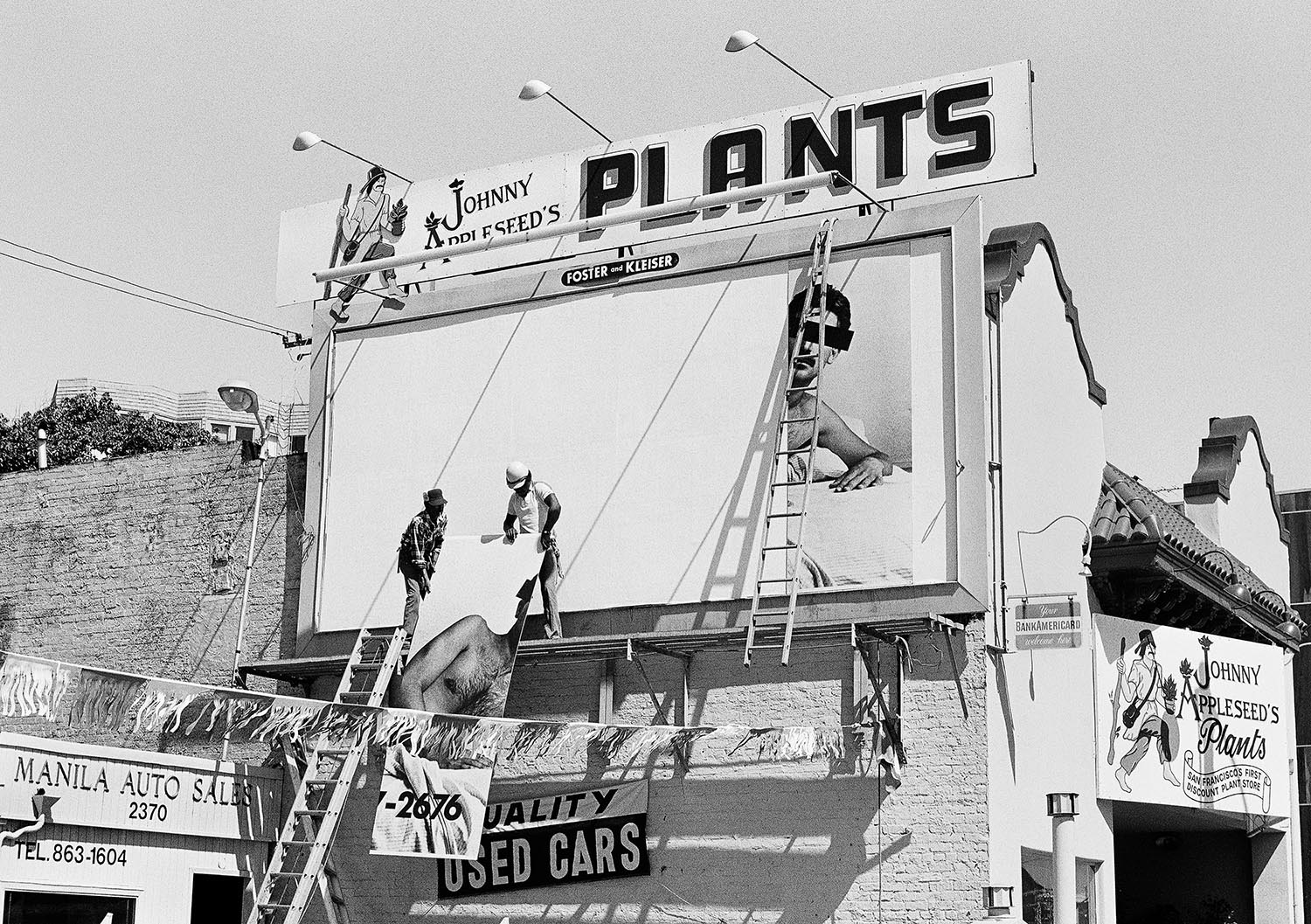

At Union Pacific, Yoan Mudry appropriates the visual language of book covers. By expanding the covers of volumes from his own personal collection — like Vinciane Despret and Joselyne Porcher’s Être Bête and journalist Anne-Cécile Robert’s La Stratégie de L’Emotion — to 160 by 110 centimeters, Mudry makes them look like stylish wallpaper or advertising billboards. This asks if reading still has anything to do with cultural capital, suggesting that living in a ‘post-literate’ age is itself apocalyptic.

Weiss Falk show us more traditional paintings, even if Mathis Gasser’s subject matter is not. Three Ships (Blue), for example, depicts great hulking spaceships in planetary orbit, or hovering over oceans and icy wastelands. Its grave tone suggests that, though humans might one day make interplanetary ‘discoveries,’ we still risk repeating the mistakes made by European colonists after 1492.

At Bodega, Orion Matin’s paintings bring together surrealism, the visual landscape of consumer society, and esoteric imagery. Naoki Sutter-Shudo’s ‘Dispenser’ series continues the troubling theme. As the series title suggests, each looks like a PEZ dispenser writ large. Inside the shaft of each piece are planets, including earth itself, ready to be popped out, swallowed, and dissolved forever in an infinite stomach acid lagoon.