Twelve paintings made by Derek Jarman between 1989 and 1990 make up the exhibition “Shadow Is the Queen of Colour” at Amanda Wilkinson in Soho. The small gallery is made even more intimate by the introduction of false walls, as if in a cloister. The number twelve resonates with the religious, the mythological, and the esoteric: there are twelve numbers on a clock, months in a calendar year, signs in the Zodiac, apostles of Christ, gods of Olympus. Jarman’s twelve paintings similarly invoke a realm of disparate references and meanings. More analogous to assemblage in their use of surface and layering, miscellaneous materials and ephemera are swallowed and regurgitated by congealed layers of thick black boiled tar.

These works — albeit smaller and more claustrophobic in their domestic scale — are an extension of Jarman’s garden at Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, where he harnessed the postapocalyptic wildness of the landscape as his canvas. He uses strokes of fury to express the anger and pain that came with his AIDS diagnosis, and outrage with the Conservative political system, environmental degradation, and consumerism. His negotiation of the local flotsam, flora, and fauna, filtered into modes of memorialization, loss, and the passing of time: an antithetical preservation of the process of decay, caught in flux.

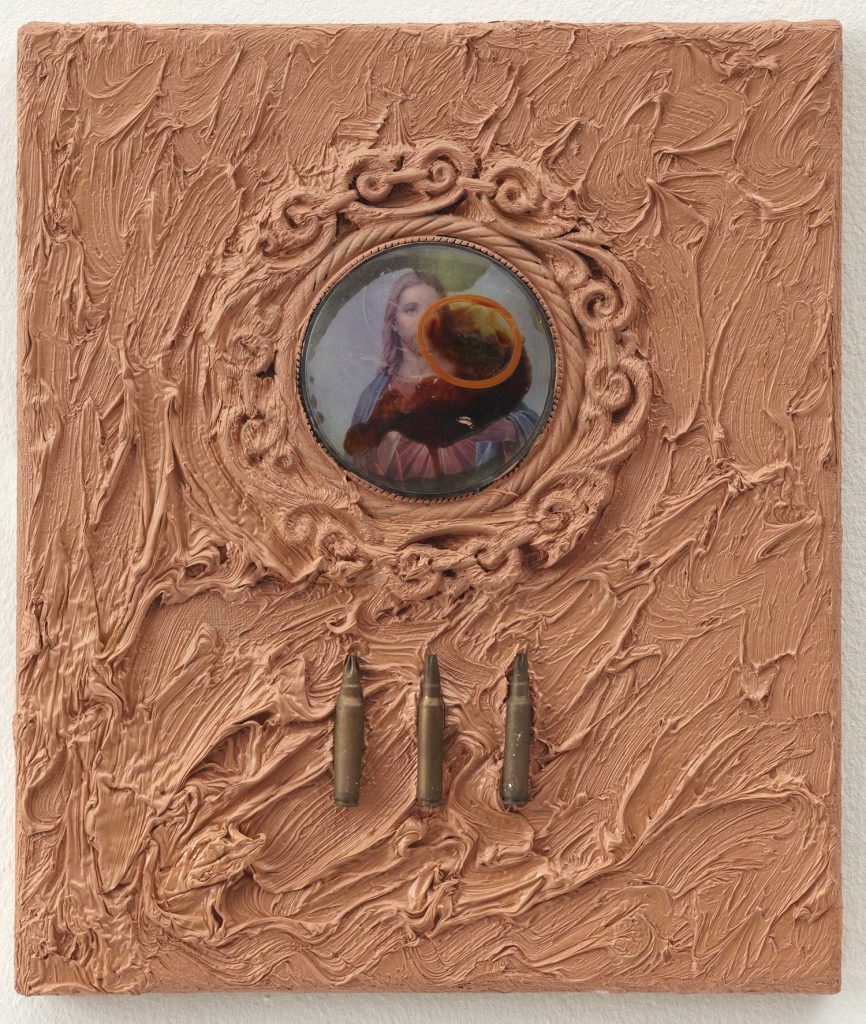

This is particularly apparent in the objects in the paintings, thrown into the hot tar as it bubbled and dried, as if the residual product of an Actionist performance. There is a clock, dried flowers, old family photographs, a miniature crucifix, a toy airplane, broken shards of jewellike glass, driftwood, barbed wire, rope, prayer books, a smashed ship in a bottle, white feathers, and torn fabric. Together, they become a collage of juxtaposed memento mori: a melting bonfire, filled with ashes. Liturgical allusions are imbued with ritualistic symbolism.

In their crude beauty and simmering rage, these three-dimensional paintings become akin to counter-monuments, designed to provoke rather than console. They demand interaction and take up space — oxygen, even — resistant in their palpable physicality. The fragmented images linger long after.