Antigone, product of the incestuous entanglement of King Oedipus and his mother in ancient Greek myth and tragic heroine of the nominal Theban play, is the subject of Tacita Dean’s 2018 film of the same name. Equally so is Dean’s older sister, whose given name Antigone first inspired Dean’s artistic experimentation with an early version of this work — a screenplay — more than two decades ago. Dean’s interest in Greek literary history focuses on the undramatized passage between Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at Colonus, a liminal period during which the banished king roams blindly through the ancient hinterland, led by his equivocal daughter-sister Antigone. The exhibition “Antigone” at the Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart combines the hour-long, two-channel anamorphic film with a selection of other photographs, photogravures, short films, and a large chalk drawing by Dean, which situate the extended filmic work in the context of this longstanding project.

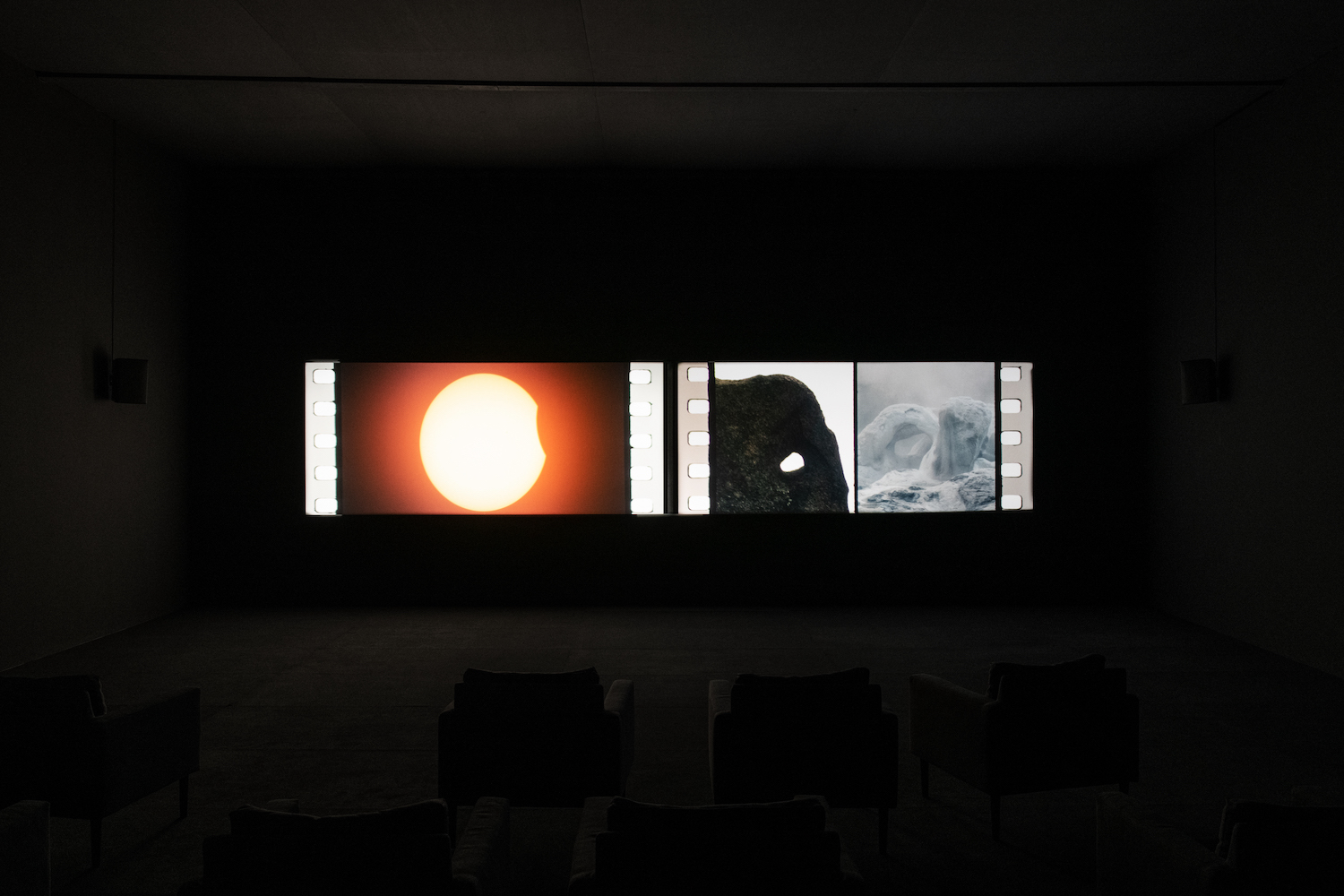

Film for Tacita Dean is a lively medium. To produce Antigone, she used a technique she calls aperture gate masking, a form of spontaneous collage that involves capturing several images on one strip of celluloid film via the use of stencils and multiple exposures. It is a relinquishment of total control over the final outcome, the process left in part to chance, though there is a marked conviviality between the images in the film. Unrelated scenes are layered next to one another: a steaming geyser next to a mossy tree root, for instance, and next to that a silhouetted figure standing in a window. The technique allows for experimentation, with several frames split into varied shapes like arcs and polygons — this composition is reflected throughout the exhibition in photographs such as Squirrel on a Wire (2018) and Ear on a Worm (2017). A stenciled outline of a foot occasionally delineates the picture. That each frame is so visually rich, and so coherent even when in juxtaposition, is a testament to Dean’s considerable skill.

The film unfolds without narrative, but follows several unscripted threads that play out simultaneously. Footage of Oedipus, played by the actor Stephen Dillane, follows the infirm king as he wanders unaccompanied through various landscapes: the churning, caloric mud of Yellowstone National Park; the arid stretch of Bodmin Moor in Cornwall; and the Mississippi River coursing through the small village of Thebes, Illinois. Dillane sports a long beard, woolen jacket, and paper eclipse glasses in theatrical, if historically inaccurate, attire. Shots of the gradually eclipsing sun, a solar event captured by Dean in Wyoming in 2017, accent the film projections in allusion, no doubt, to Oedipal blindness.

Interspersed through these environmental images are scenes depicting Dean and her collaborators, Dillane and the poet Anne Carson, who occupy the hilltop courthouse in Thebes. The group read aloud Carson’s poem “TV Men: Antigone (Scripts 1 and 2)”and discuss the characters in question, their voices overlapping and discordant like an inharmonious chorus in ancient Greek tragedy. Through the din of voices, a question resounds: What fate does a name assign to its wearer? Over the film’s duration, a tension unfolds between the notion of destiny and that of moral judgment, the latter emphasized by the colonial courthouse. Though Oedipus has blinded himself in retribution for his incest, the three colleagues return again and again to the question of providence. Antigone, they conclude, was destined to be held in suspension: she is both geographically and personally in-between, as neither daughter nor sister, and as guide to her ailing father while he wanders from site to site. “To the ancient Greeks, dirt was matter out of place,” recites Carson to the others, suggesting that Antigone’s sullied condition is due to her nonspecific status. She is unclassifiable. Yet the three agree that Antigone and Oedipus were destined to carry out their roles, the ancient gods less interested in their purity than in the fulfillment of their story.

Dean challenges the binary of purity and corruption, however, knowingly disorienting the primordial categories of light and darkness to do so. “The moon is beautiful, but the moon is more beautiful obscured by drifting clouds,” notes Carson in her whispery voice, the sentiment resonant with the fragmentary visual quality of the film and the exhibition material that surrounds it. Each image is made all the more compelling when spliced and set in relation to others. Dillane later recalls a saying that the sun is a “clod of light,” relating the great celestial body to earthly matter. As well, the footage of landscape bathed in both darkness and light implies nature’s indifference to anthropic values of integrity and virtue.

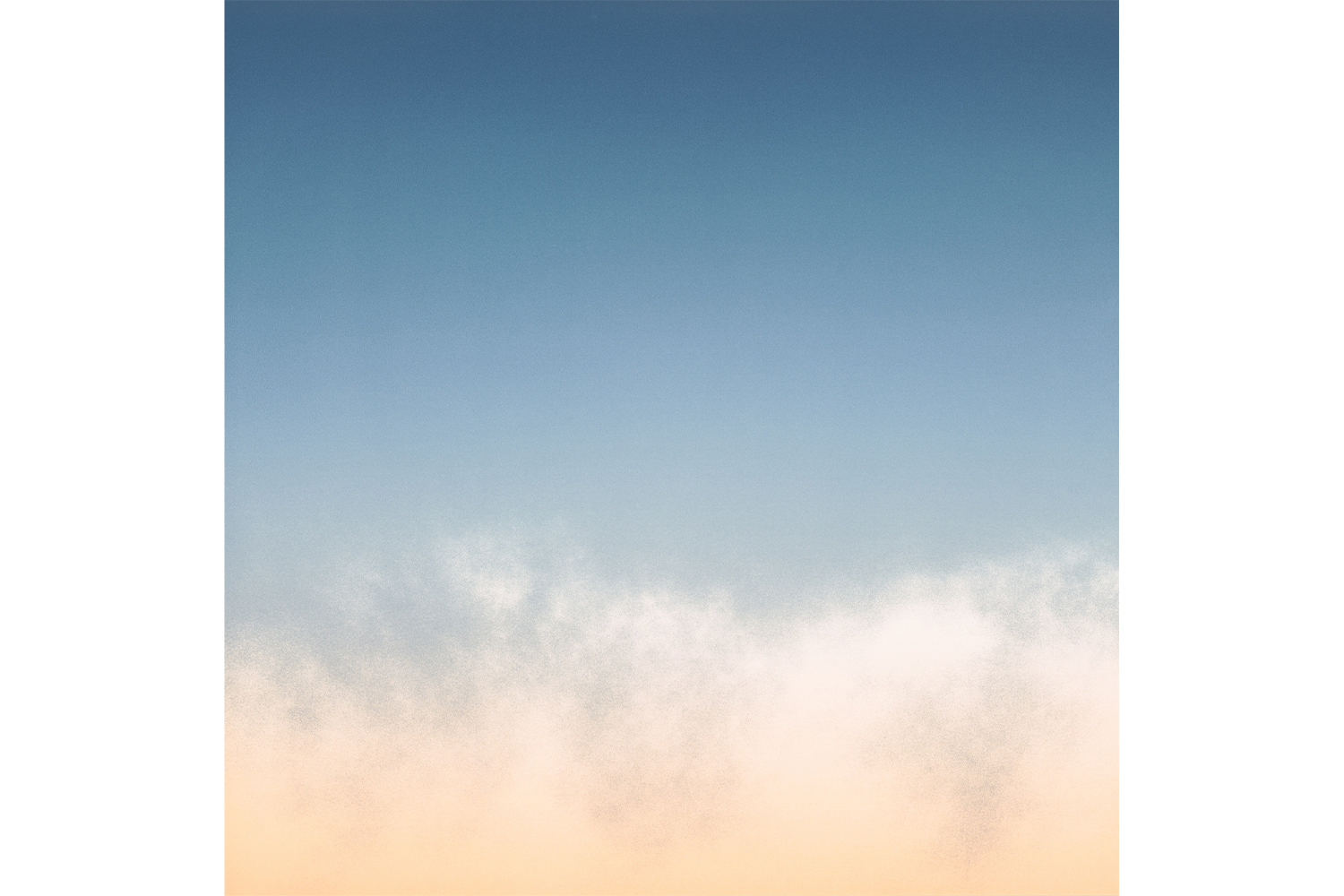

A final scene: the projections synchronize to depict a magnificent, perhaps godly, blood-red sunset. Yet the sound of a plane’s rumble is a reminder that this divine light is nothing but an effect of contamination. In gesture to this final panorama in Antigone is LA Magic Hour (2019–21), a series of ambrosial photographs of softly tinted clouds against an azure sky. Where better than Hollywood to stage imagined perfection amid extraordinary pollution?