“Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

— Margaret Atwood

William J. Simmons: I was driving around today, and Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space” came on the radio. Taylor says, “Boys only want love if it’s torture / Don’t say I didn’t, say I didn’t warn ya.” In the context of Promising Young Woman, it makes me think about how Carey Mulligan both tortures men and points out the torture that men inflict on women. Then I thought, isn’t she torturing herself for the death of her friend? Honestly, some part of me thought that she might have been glad to die at the end of the film. But maybe I’m crazy!

Lauren Mayberry: That’s very interesting about Taylor. I didn’t think about “Blank Space” in that way at the time, but it definitely feels like she’s gone on a journey in terms of exploring female anger in other songs since then too. All of Reputation played with that kind of aesthetic, and one of my favorites off Folklore is “Mad Woman.” “When you say I seem angry, I get more angry” and “Women like hunting witches too” — it feels like that second half could be applied to the Alison Brie and Connie Britton characters. I do think that’s a part of the post-#MeToo conversation that we haven’t fully got to yet: how women internalize their own misogyny and direct that towards other women. “Patriarchy” doesn’t mean “men.” It is a system designed and orchestrated predominately by men, but women can benefit from and be complicit in that system too. To me, the discussion around dismantling patriarchy means dismantling the systems, not attacking men (as much as sensationalist men’s rights podcasters would have you believe that). I always enjoy any investigation of female rage in art. It makes a lot of sense to me that Emerald Fennell, who wrote/directed/produced Promising Young Woman, was also involved in Killing Eve. Tonally, it feels like there is a commonality between the two, but Promising Young Woman is much darker.

I think it’s interesting that the thing that pushes Cassie over the edge is something that happened to her friend, not something that happened to herself. I think that in itself is a comment on a stereotypically female trait — to see wrong when it is done to others, not necessarily when it’s done to yourself. It speaks about sisterhood, and how at the end of the day it’s women who take care of other women.

It’s like Cassie one day just reached her “fuck that” factor and couldn’t stand to play the game anymore, and I think 99% of women who watch the film can identify with that. You know the smart, sensible, advisable way to handle certain situations, but sometimes you just want to burn the fucking building to the ground. There is so much patience and bargaining and analysis involved in being a woman, whether that’s figuring out how flirty you need to be in response to a creepy cab driver who is taking you home, or in the workplace, at home, or something much more sinister. There’s a freedom in watching a fictional character refuse to play the game anymore.

I agree that the ending is very important. If she had survived and managed to avenge her friend, everything wrapped up neatly with a bow on top, it would have been too unrealistic. The fantasy elements of the film needed to be balanced out by something so painfully true. Even a woman hell-bent on murderous revenge is, at the end of the day, still smaller, physically weaker, and more vulnerable.

How do you feel about the defenses offered by the dean of the university and the rapist’s friends? I feel like the “boys will be boys,” “everyone should be allowed to make mistakes when they’re growing up” arguments are thrown around quite freely, even after Time’s Up. Yes, everyone makes mistakes, but the young man in the film makes a “mistake” that irrevocably harms another person. What is the answer when your actions have arguably graver consequences for other people than they do for you?

Linked to that, how do we assess when someone has atoned? I think that’s one of the hardest parts of the present discussions of “holding people to account.” Is there space for rehabilitation and atonement? When? Who decides? I sometimes fear that by cancelling people instead of actions or behavior you just cut off one head for two to spring back up in its place. Again, it’s not “men” that are the problem; it’s “patriarchy,” and I do feel like we have to figure out how to change the way we grow up — men and women — in order for that to ever change. Patriarchy isn’t good for men either.

WJS: Speaking of Killing Eve — there was a lot of discussion about Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag being “relatable” exactly because Fleabag could be seen as self-destructive, turning misogyny inwards, to use your spot-on formulation. Lena Dunham’s Girls and Taylor Swift’s work in their own way address this self-destructive-and-therefore-relatable female protagonist. Is being in some way traumatized the only way for a female protagonist to be normatively “relatable” onscreen?

Back to Promising Young Woman, I love your idea of the film revolving around sisterhood but also the potential for that sisterhood to be violated by internalized misogyny (as with the ever-iconic Connie Britton character). At the same time, the film is also about the most toxic form of “brotherhood,” which always acts in its own self-saving interest. We saw a spectacular and sad example of this with Christine Blasey Ford and Brett Kavanaugh. Society is always willing to give men a second chance, unless of course you are Black, which points to not only a gender disparity but also a racial one.

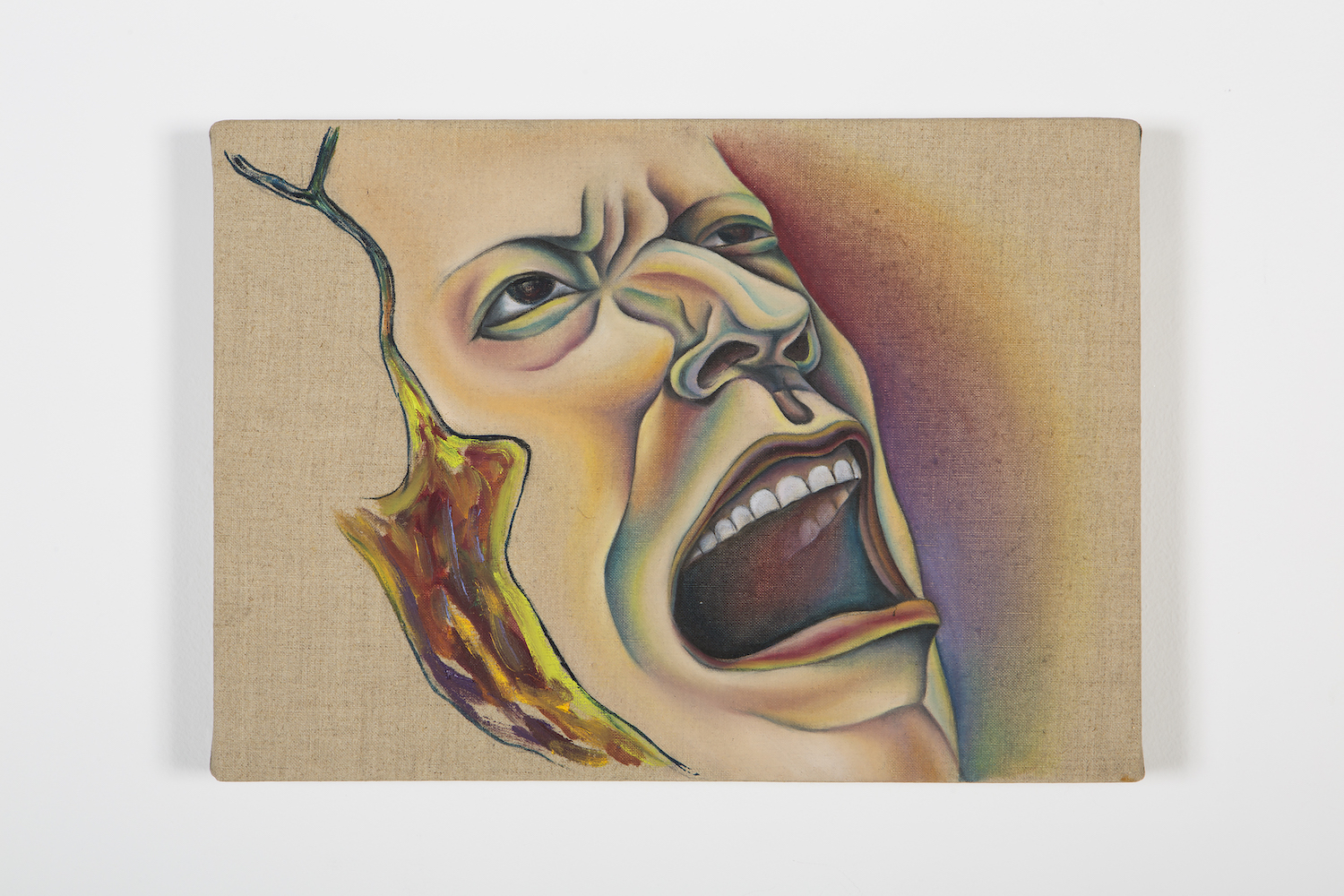

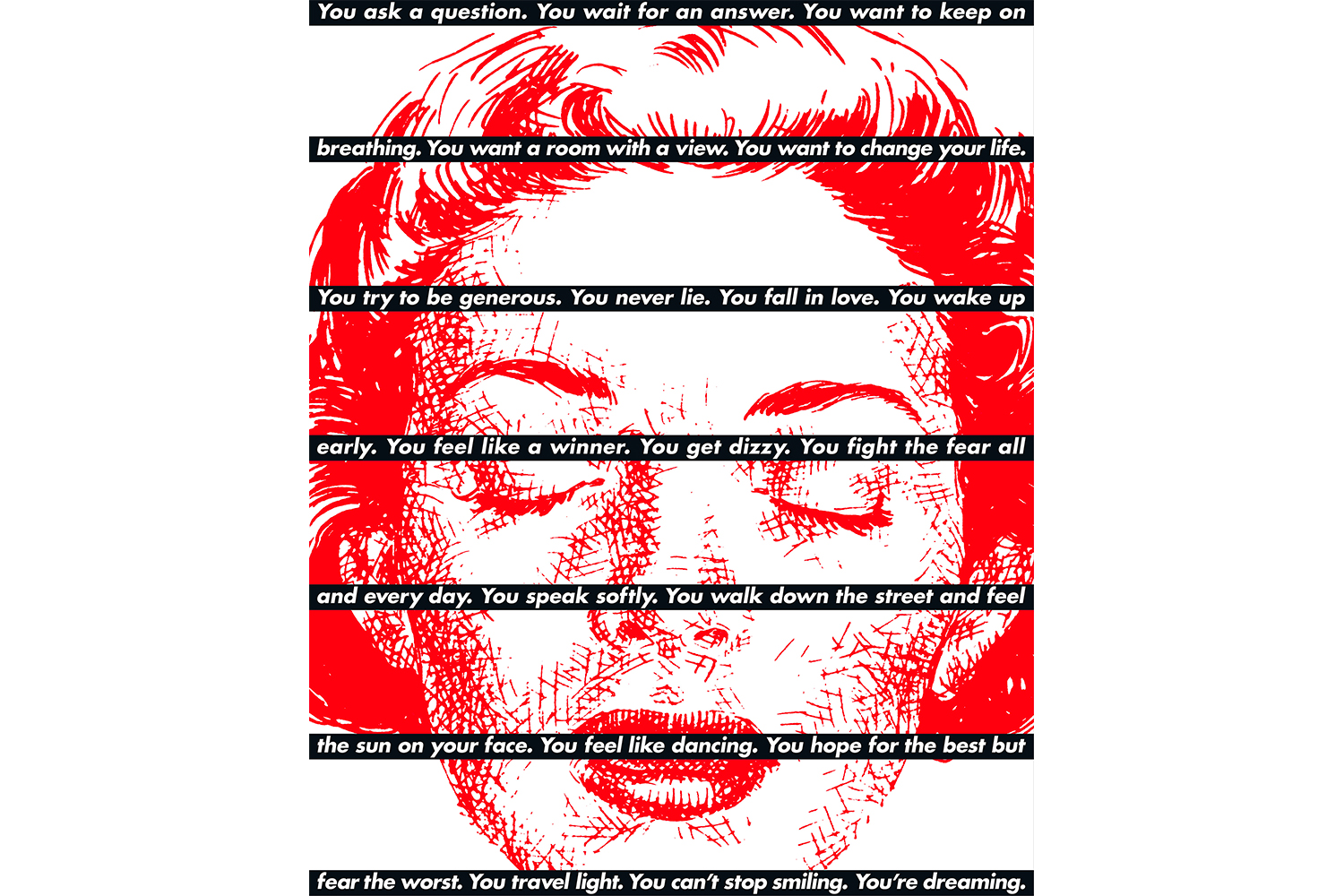

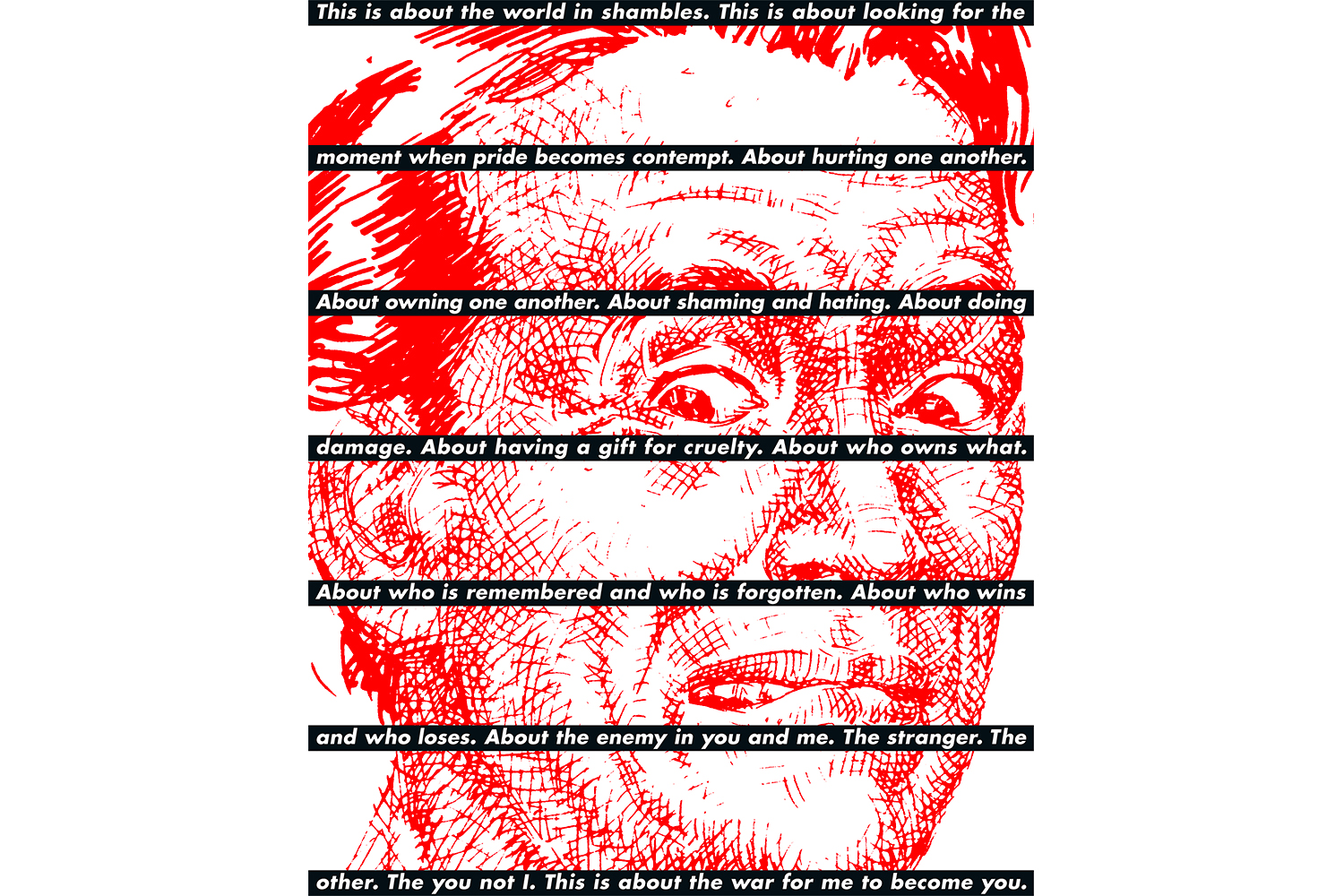

You’re absolutely right about this question of cancellation and atonement, because cancel culture (while having accomplished some necessary things) sometimes does not address systemic issues like patriarchy, racism, and homophobia. I am reminded of Judy Chicago’s “PowerPlay” series (1982–87). It is an essential part of toppling the patriarchy, to use Joey Soloway’s phrase, to image/illustrate its violence, so that it can no longer protect itself and operate invisibly. And just to clarify, I think that “tragic woman is relatable” trope has less to do with the works themselves, but rather their reception. Like, we as viewers disallow non-male pleasure.

I have to ask: How iconic was the “Stars are Blind” scene?

LM: “Relatability,” when it comes to female artists, writers, performers, is an essential prerequisite that seems to apply a lot more to women than to men. I wonder why that is. On the internet and in the press, it seems like we condemn women for not being relatable in a way we don’t with men. Obviously, there are exceptions to that rule (Missy, St. Vincent, hosts of other avant-garde artists), but it’s almost like the personality of the artist is expected to be relatable when it comes to women, and I think that speaks to a societal comfort with women occupying certain roles. We have to believe that these artists are somehow occupying pre-identified roles, so we can feel better about the parts of them that are “taboo.”

Maybe straight white men can relate a lot more easily to most stories told to them through art because most of those stories were created by people who share their experience. The last five years in TV and film has been a real game changer for me because I can relate to characters that are getting a platform — Fleabag, Killing Eve, I Hate Suzie, I May Destroy You, Insecure — because women are getting allowed to create their own content in a more mainstream space. The nuance of those stories is down to great writing, borne from observation and experience, and it’s very powerful to see and feel those stories being told.

Regarding the Paris Hilton moment, I loved it and think it speaks to the tongue-in-cheek nature of a lot of the writing, which is a weird but very effective juxtaposition to all the fantastical violence. I think those moments are important to keep her from seeming like a superhuman and meaning people can end the film thinking, “Yeah, but it’s not real or relevant to me. Why do I need to learn anything from this?” I also love when films and TV really use music as a part of the story, rather than just a soundtrack or quietly hidden score. Killing Eve does a lot of that too. It outlines a mood or a moment with the song choices, so, as a musician, I get over-excited when those things happen. I think it speaks to the artistic generosity and awareness of the creator too, if they have awareness and respect for other art forms, be that music, visual art, graphic design, whatever it may be. I have always found those kinds of collaborations exciting, as an artist and as an observer. I loved the styling and the color palette too. It felt contemporary but also harking back to a classic era of super stylish horror, paying homage to that but with the roles finally reversed.