At Hauser & Wirth, seven works by the late Mike Kelley, mostly sculptures isolated from their conceptual contexts, sit with twice as many works from artists associated with the show’s curator, Jay Ezra Nayssan, and his in-home Santa Monica gallery Del Vaz Projects. The show’s title, “Nonmemory,” is defined in the exhibition text as “a way of treating, reordering, and representing the complex and unstable relationship between memory, space, and identity.” I might argue that these are core concerns of artmaking in general, but those familiar with Kelley’s oeuvre and extensive self-theorizing will associate the title with his interest in repressed memory and the societal impulse to fill these gaps with the scandalous and macabre. There is very little scandalous and macabre work in this show, which is an achievement considering it’s centered around Mike Kelley.

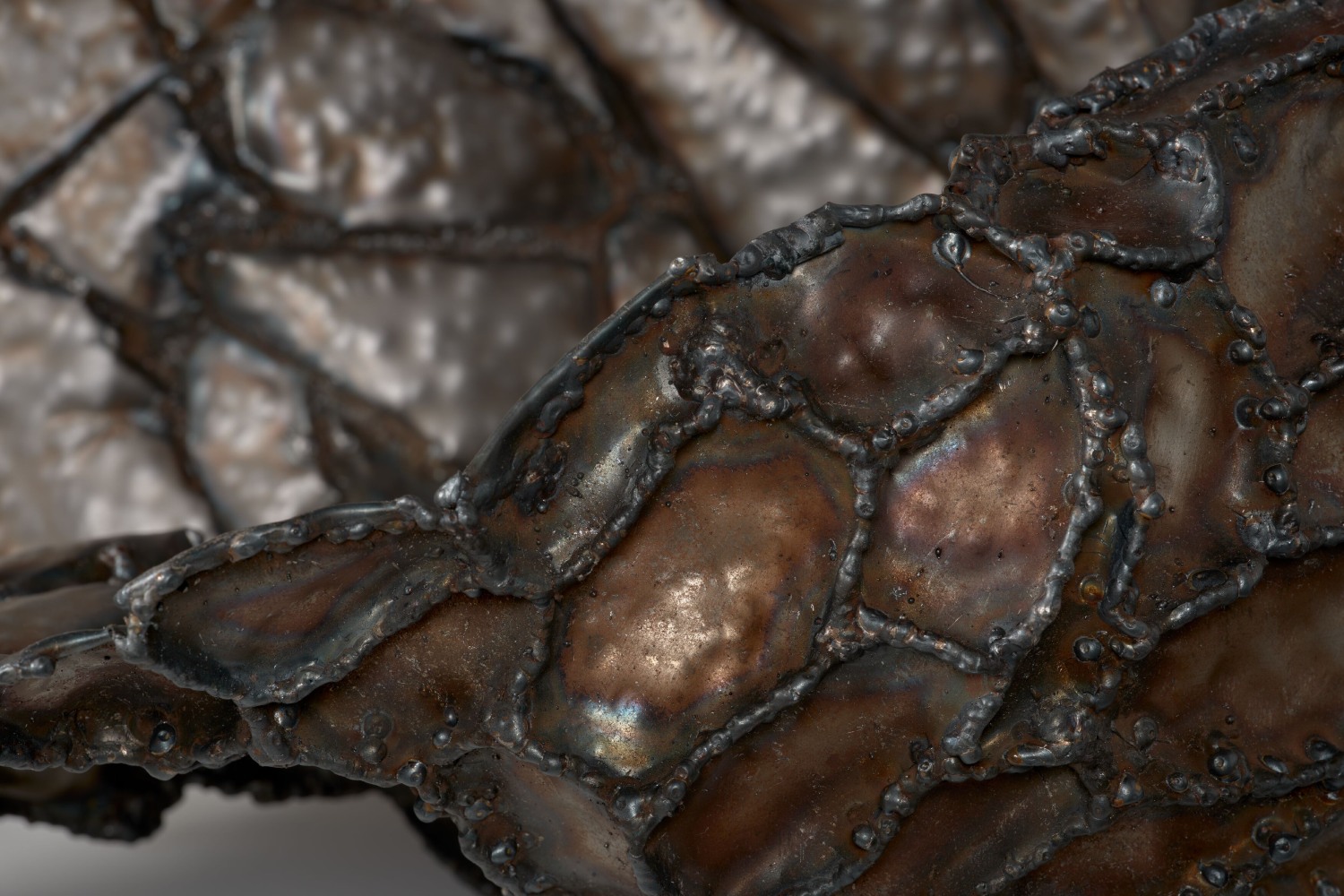

The work is grouped by superficial stylistic similarity. There is a gallery full of objects resembling chunky rocks, a gallery with works made of little colorful bits, and a section where the theme can probably be described as “architecture.” In the rock room, I was taken with Cultivator Cavern (Thorned Truss) (2022–23), a smaller-than-usual stone-and-wax work by Kelly Akashi. As Akashi’s work becomes grander, its center becomes more subtle, and is often sublimated into technique. There’s more than a little art history in this work, but it’s less pristine than I’ve come to expect from Akashi, and the piece feels motivated by cultish devotion and internal compositional interactions. In this gallery is Kelley’s Kandor 16 (2011), from a body of work that seems in constant rotation at galleries and institutions but that, in my estimation, is some of his most pandering and conservative. Beatriz Cortez has rocks in this room, too, and they’re made of metal. Her sculptures are welded out of small panels of steel, like quilting. They sag and breathe organically, wonderfully, at odds with their material. Unfortunately, the entire gallery is dimly lit (in tribute to Kelley?), making this detailed work, already dark and low to the floor, especially hard to see.

In the tchotchke room, Max Hooper Schneider and Raúl de Nieves are paired with one of Kelley’s classic wall-mounted accumulations of buttons and notions, in an act of visual association I can only describe as literal. Probably because they were next to each other, I found myself comparing Kelley’s obsessive collecting with Hooper Schneider’s. While Kelley’s work is decidedly theatrical, one of its central concerns is real-life vernacular animus as setting rather than the indexicality of symbols. Kelley’s buttons and notions are, if anything, banal, scraped from the shelf of a midwestern thrift store at random, exactly the kind of objects that silently bear witness to our lives. Hooper Schneider’s accumulations seem more indexical, purchased for art and acting as representational stand-ins. Kelley works with the taxonomy of experience, while Hooper Schneider works with the organic mold-like accretion of symbolism. This isn’t to say that Kelley’s work feels more vital here, as both artists are dominated by the passions of de Nieves, whose detailed and personal collages manage to accommodate both the world and its symbols. Similarly, Lauren Halsey’s dat fuss wuz us (2023) feels authentically Kelley-like as a complex grouping of “found” and fabricated objects that manage meaningful obsession without either fussiness or carelessness.

The most physically and durationally substantial works in the show are also the best. A pair of eighty-minute videos, documenting a near-scale model of Kelley’s childhood home, driving east and west on Michigan Avenue in Detroit, acts as an excuse to document local culture and characters, to make sets and soundtracks, in a strange and tender constellation that captures the spirit of the late artist beautifully. The videos are an excellent example of Kelley’s relationship to memory and materiality, and they feature all of Kelley’s creative modes, from sculpture to cinema to music.

While there’s no way to know what Kelley would make of “Nonmemory’s” relationship to his concepts and imagery, it is a reminder of his deep intimacy with the subtleties of vernacular form, which expresses itself here as the ability to quietly align and even disappear within the work of a generation of younger artists. Separated from their larger bodies of work, Kelley’s objects are perfect chameleons. A viewer could be forgiven for imagining him as mild and withholding, a quality he detested in art. It’s unclear if this disguise is part of his project. He often expressed how important it was that his work was available to both the most and least art-acculturated audiences. It’s possible that a version of that is happening here, but it doesn’t seem like the show knows, either.