Kiko Kostadinov: I was thinking about Prada. When I had the privilege to interview Olivier Rizzo almost seven years ago, he was explaining how before the show prep, even the morning of, they will check the shows and the show that happened two hours earlier, and if it’s similar to the collection in terms of look or styling, they’ll try and change. I can’t say it’s last minute exactly, but it’s so reactionary, which is brilliant.

Eric N. Mack: There’s so much radicality in thinking about the role of time in fashion. There are competitive markets and competitive imaging. But there’s also something more spiritual that I find interesting, a sort of zeitgeist moment when the same muse is whispering in everybody’s ear.

KK: This is very true when it comes to hair and makeup, as well as styling. I think it’s something quite close to doing an exhibition. When we see the building of a “look,” we see it on one person at a time. The pre-styling is very isolated, but the real magic happens when you see all the models dressed in, having their show hair and makeup. Together, they become art. Before a fashion show, when I see the lineup backstage — all of the models wearing makeup, clothes, and shoes — I think, “Wow, this is the body of work.” It is not about the singular pieces; it is not about the cool jacket or the shoes that we have been obsessing about for months. All the pieces talk to each other, and I suddenly feel like I’m living in a fantasy because all the characters that I’ve created are finally interacting with each other. I guess that’s how your work comes to life; the pieces start talking to you when you see them in the space.

ENM: There’s so much embodiment in the physical form of the model wearing the clothes, and they become your people, your women, your men, concretizing this concept of how you plan to affect the everyday. And that’s why it’s so nice to see kids on the street wearing your looks in real life. I thought, “Oh, this is straight from the runway, but this is also somebody kind of taking it on as their position for the present moment.” It felt like their chosen language, a visual language for the day. This also happens with my work. There have been moments and epiphanies where I thought, “Okay, this is effective, and it’s mostly so because people are interacting in this space and experiencing the work.” You know something’s working when there’s a vibration or correspondence between the viewers and the work.

KK: I remember seeing your show “Lemme walk across the room” at the Brooklyn Museum in 2019. When you moved between the works, getting closer and further away, they were moving as well because, as you once said, they’re not fragile but lighter.

ENM: And they are responsive. If you stand next to a piece of work and breathe hard enough, it will move.

KK: Closeness is very important to me, too. It’s fundamental that the people who come to my shows and care about clothes can be close to them. I always keep that in mind, even if sometimes they get too close. I want people to feel the fabric touches them.

ENM: The last few runway shows I’ve seen of yours were very interesting because the space of choreography, this kind of structured movement and proximity to it, talks about the movement of the fabric and within a kind of control. It’s like a short movie, you know what I mean? To see the density of the material, you can feel the density of the silhouette, that kind of off-balance heavy boot and this lightweight, voluminous wool jacket. It’s so satisfying to be able to witness the movement and pacing, the attitude of the models. It’s something that’s completely connected to real life. When making a show, I think more than anything, I’m trying to consider the space, how I want people to feel, what viewers are left with after experiencing the work, what’s communicated to them, and what other spaces they deem possible. I want to privilege myself as a viewer of the work as well. It’s like me sitting alongside my most trusted viewers, people who I respect, even though we’ve never met. I need to be able to sit beside them and look at the work in a completely objective way to feel moved and to see a pathway or stake that the work represents.

KK: You respect other artists; you want to see their shows and what they are doing and how they are doing it.

ENM: Looking at art is about linguistics as well. And it’s the very same language that people will be using with my work. I have to be equipped with it as well.

KK: That’s why I sometimes wish I didn’t know so much and I didn’t get so obsessed over clothes. Because the more you know, the more you can use it to your advantage. But I’m not here to cheat the system — using cool vintage pieces by picking more modern materials. I quite like the idea, but I feel we both come from this point where all that matters is the physical work and just going through the investigation process. I realized that the more you travel and meet new people, the less time you have for the work. There’s always somewhere you have to be — exhibitions openings, art worlds, fashion shows, pop-up stores, shops — and you’re just like, “Oh, I just want to be in the studio.”

ENM: I draw much inspiration from my travels. It’s usually a response to a specific place. This humanmess — the evidence of people living in the cities — reminds us why we do what we do. Whether that happens here in New York, Italy, London, or Paris, the space we inhabit constantly reminds us that we need to be back in the studio because there are things to be made.

KK: For me, I think it’s different because I have a pretty defined work schedule. Going forward, I might change it slightly, but I like the idea of six-month collections. I don’t need to come up with a new storyline every season. I find it easy to look at new ideas and reference something current, but trying to be your own editor of your past work is quite tough. I feel less confident because, with new ideas, you can always hide behind, “Oh, I’m just trying something new, you don’t get it!” But to stand and say, “This is my language. I have owned this idea for over six months,” I find it challenging. How does it work for you now that you’re experimenting with new suspensions for your show at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York? Do you feel this is something new, or has it always been there?

ENM: These metal armatures you see here in my studio are a pretty strong statement. They’re not solely about the history or the experience of viewing painting, but more about the language of architecture.

KK: What do you call them? Mobiles?

ENM: Yes, mobiles. I think Alexander Calder coined the word “mobile.” Or maybe it was Marcel Duchamp who saw them for the first time and gave them this name as a gesture of movement and suspension.

KK: When your structures are bare and undraped, they resemble mobiles. But once they’re dressed, when they have something on them, they completely erase their starting point.

ENM: The structures are very solid and firm. But they’re just surface play because the aluminum reflects the light, making the whole work light and free and in movement.

KK: You’re very specific about this. It all feels quite reactionary in the moment. In fashion, everything is super detailed. Do you also have ten or twenty options for the thickness of aluminum? Or can you be rougher and kind of work with it?

ENM: For this show, we did renderings from the drawings. I anticipated what form the fabric would take. A lot of times, it’s based on ways I’ve experienced the same material in previous works. The mobile is a problem- solving mechanism in which the structure will not be contingent on any kind of wall space. It can be autonomous and operate within its own cycle. This is a shift in thinking for me, which I’m excited about.

KK: This is why I’m so curious to see where this is going once the works are installed at the gallery. I’m trying to imagine something completely opposite from what you’ve done before, something that opens a new door to another process. That is very exciting for you, especially because people often try to push you into boxes.

ENM: It’s also about the opportunity to be placed in the center and remembering what that means and what you’ve learned from that position. When I installed Sarong (2023) for “Chronorama Redux” at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, there was a very ambitious architecture to take on, this grand palazzo.

KK: What would have happened if it hadn’t been placed in the middle?

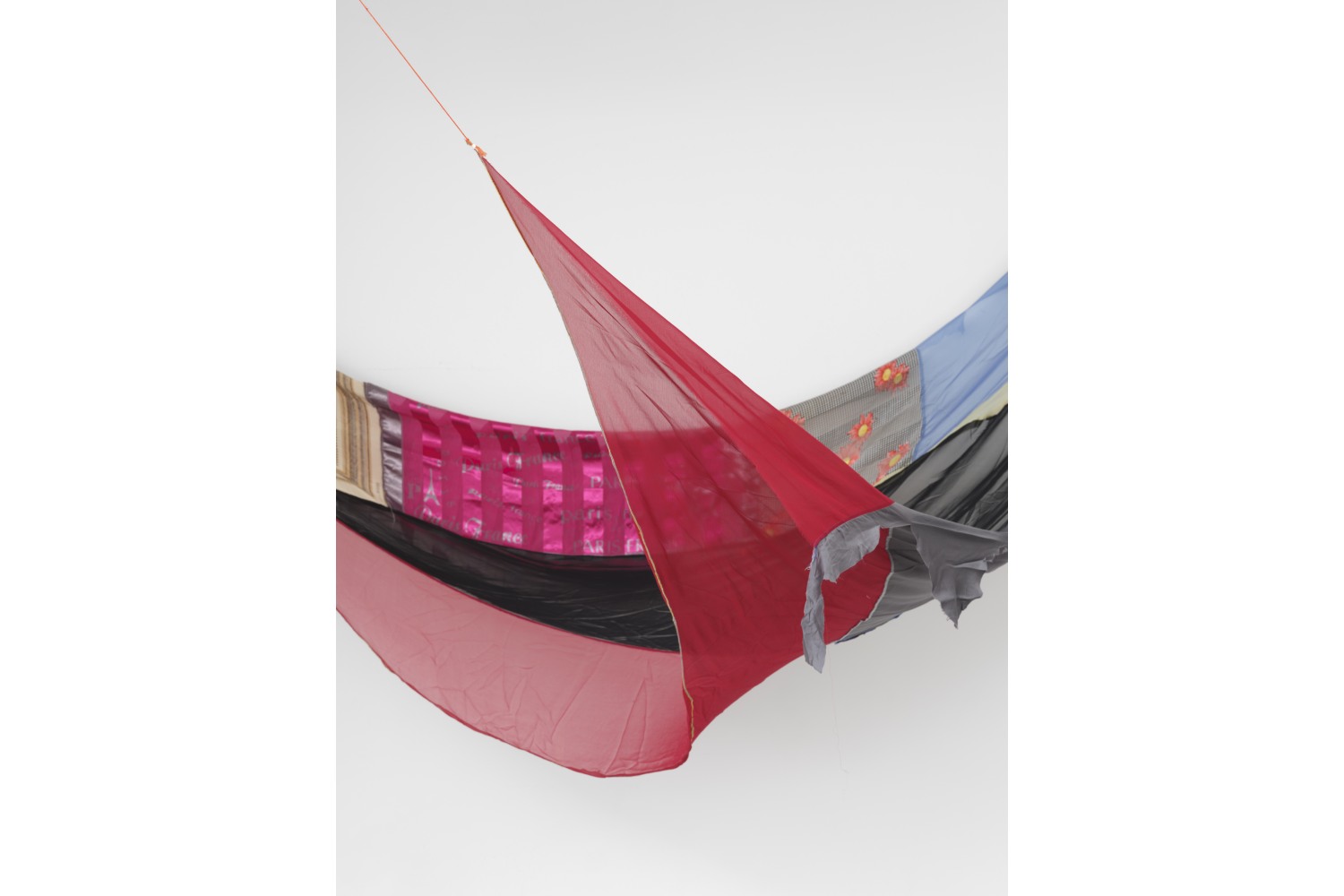

ENM: There were two aspects of that. I had this concept of a hammock as a container in my mind. Not necessarily a container for a body, but for anything. Anything can go in this space. One can be enveloped, imparting meaning by just thinking about the importance of this iconic, simple form of fabric with two points of connection. So they just swoop down. Compositionally, that’s just a curved line with a volume. To allow that to happen properly, it had to connect to the opposite side of the building as a point of suspension.

KK: I can see many people appreciating the color combinations of the fabrics covering the mobiles.

ENM: That’s the whole thing. It’s a big part of the work and the consciousness of it, whether I was making paintings with acrylic or oil or whatever. Because it’s made out of fabric, I want it to communicate back to this other world. They feed one another.

KK: The mobiles are quite interesting because you can’t really do that. It will challenge people to push their drapes or create a silhouette…

ENM: I love that, though.

KK: I also quite like the principle. It’s not garments that have been taken apart; it’s fabrics. You are working with raw materials rather than preexisting objects that might be easier to understand. I think this is what separates your body of work from that of other artists who also use fabric or textiles. It’s easy just to go and get a lot of nice vintage stuff and cut them apart and sew them back together and then, automatically, it just becomes something.

ENM: Because it was already something.

KK: Your approach to fabrics takes me back to when I was working on my Stüssy collection. I never touched anything. I was like, “If the overlock is white or green or black, I just go with it.” I never wanted to restart and unpick; I just wanted to continue where I left it and be part of this moment — again, going back to being part of the moment. Even when I was recutting the jumpers, I never threw anything away just because they didn’t work. I forced myself to use them and just finish the work. I can see you doing the same in your practice, and you continually challenge yourself to finish a piece and see it through.

ENM: That’s the nature of the work. I need there to be this thing that will attract your eye from across the room that you won’t see anywhere else.

KK: Do you see yourself developing your own fabrics in the future?

ENM: That’s definitely the next step for me. Having things that are rarefied and wild and that I haven’t seen before, but also things that I think we can all just use. Something very useful to cover, like this chair I’m sitting on.

KK: Our first collaboration is in text rather than a product. But we should consider doing something together at some point in the future.

ENM: I could style your show! That would push my concerns about the work into a space where art can exist. It would be like an embodiment of the studio’s space to extend the practice so others can experience it, recognize it, and locate the work. Younger people who live in both the art and fashion world can put those things together; they are really paying attention in that sense. Our having this conversation proves even more that there is a shared space. It’s not embattled. We speak similar languages, which are being retooled and economized for various means and ends.