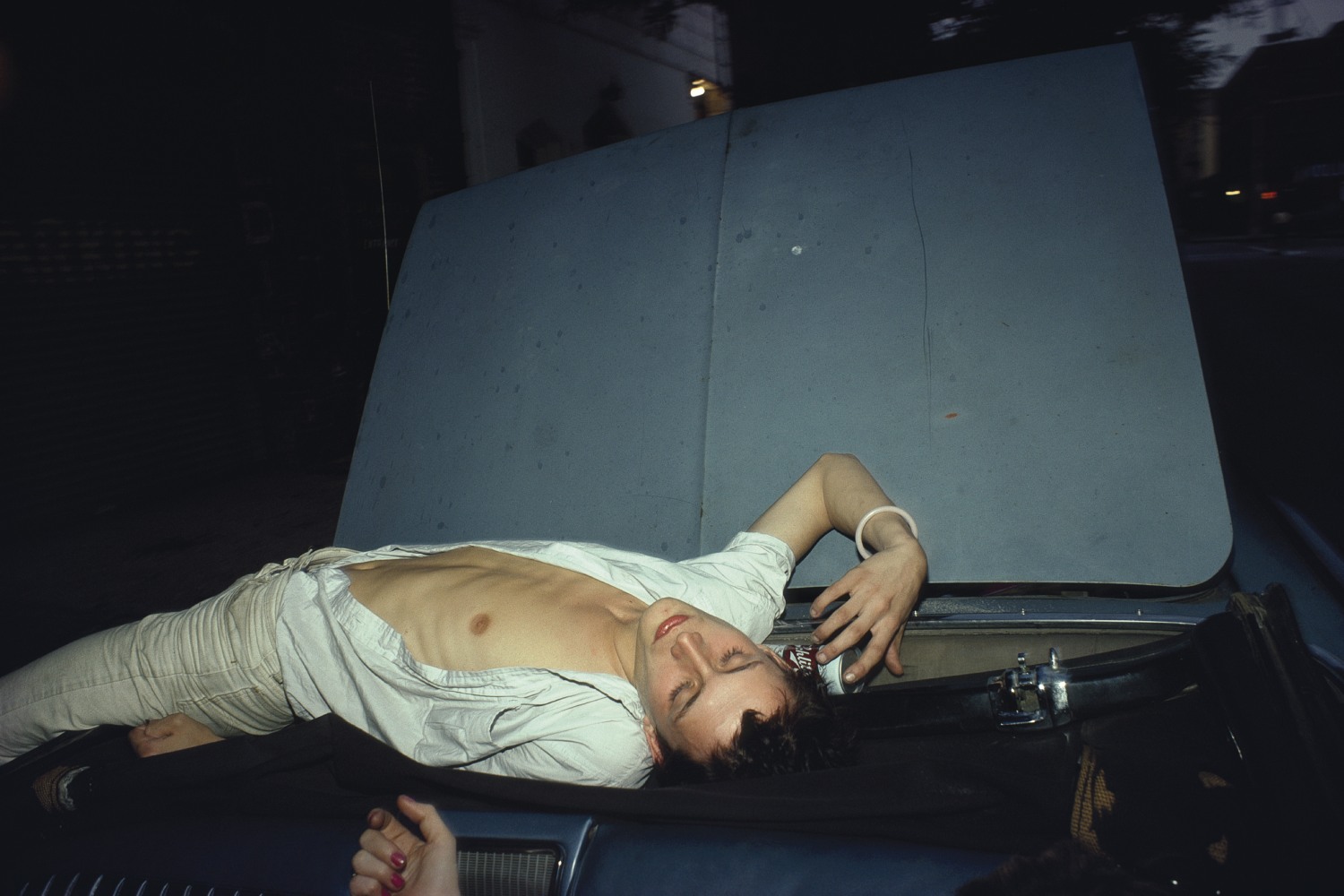

“My whole life is based on memories. I remember everything that’s ever been said to me,” Nan Goldin remarks in a voice-over as part of the slideshow Memory Lost (2019–21), a work that deals with her personal experience of drug addiction and concurrent memory loss. A continuous stream of photographs, many of which are damaged, unfolds to a soundtrack of strings and worried voicemails left for the artist by her friends. Blurry pictures of skies and beaches slip in and out, the way memories sometimes do; attempting to hold onto them would be futile. This is how Goldin initially presented her photographs in the 1980s to live audiences in clubs and underground movie theaters all over New York, and it is how they are presented here, now, at her new retrospective titled “This Will Not End Well.” The exhibition, which traveled from Stockholm’s Moderna Museet to the Stedelijk Museum, is the first comprehensive overview of the artist’s work as a filmmaker. While most people know Goldin as a photographer, she has “always wanted to be a filmmaker,” sometimes describing her slideshows as “films made up of stills.”

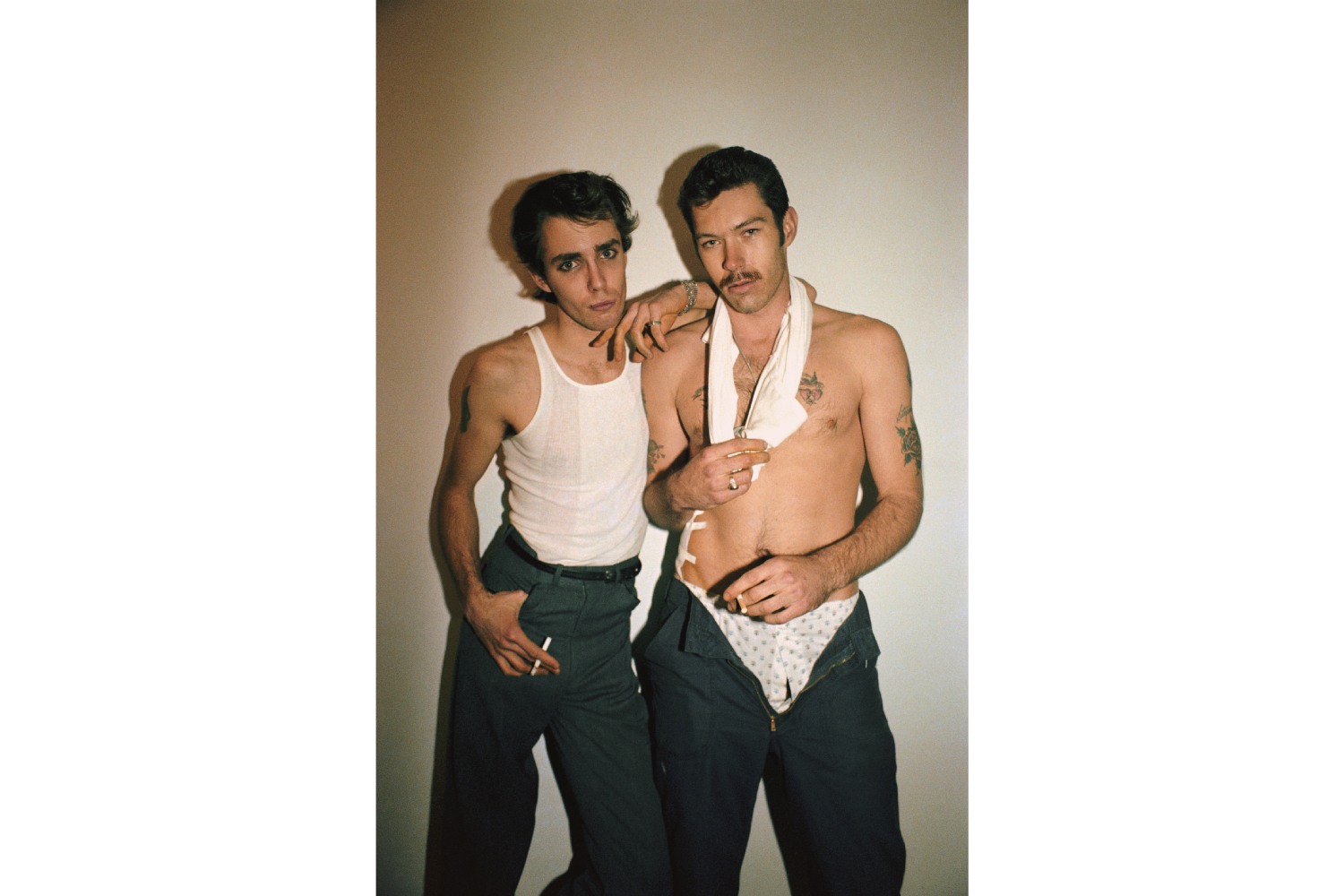

The six slideshows that make up “This Will Not End Well” — which includes Goldin’s magnum opus, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979–86), as well as more recent works — are housed in tent-like buildings, each designed by architect Hala Wardé in response to a specific piece. They are clad in a thick, dark gray fabric that keeps light out, sound in, and is soft to the touch. Together, these sober structures constitute a village that fills up the Stedelijk’s massive lower-level gallery. Since its opening the exhibition has consistently drawn big crowds, and while it is busy during my visit, the atmosphere feels safe and intimate as soon as I’ve found my way into one of the felted architectures through a discrete crack. I nestle down to watch The Other Side, an homage to the transgender friends that Goldin lived with and photographed regularly between 1972 and 2010. Young dolls pose tenderly in their bedrooms, flamboyant queens are captured at drag bars and pride manifestations. Peggy Lee’s classic “Fever” fills my ears. I bop my head to the rhythm, an elderly person next to me sways their shoulders. The clicking sound of the analogue projector brings me back to the slideshows my grandfather would compose for family gatherings, packed with remnants of his longgone days of hippiedom and bohemianism.

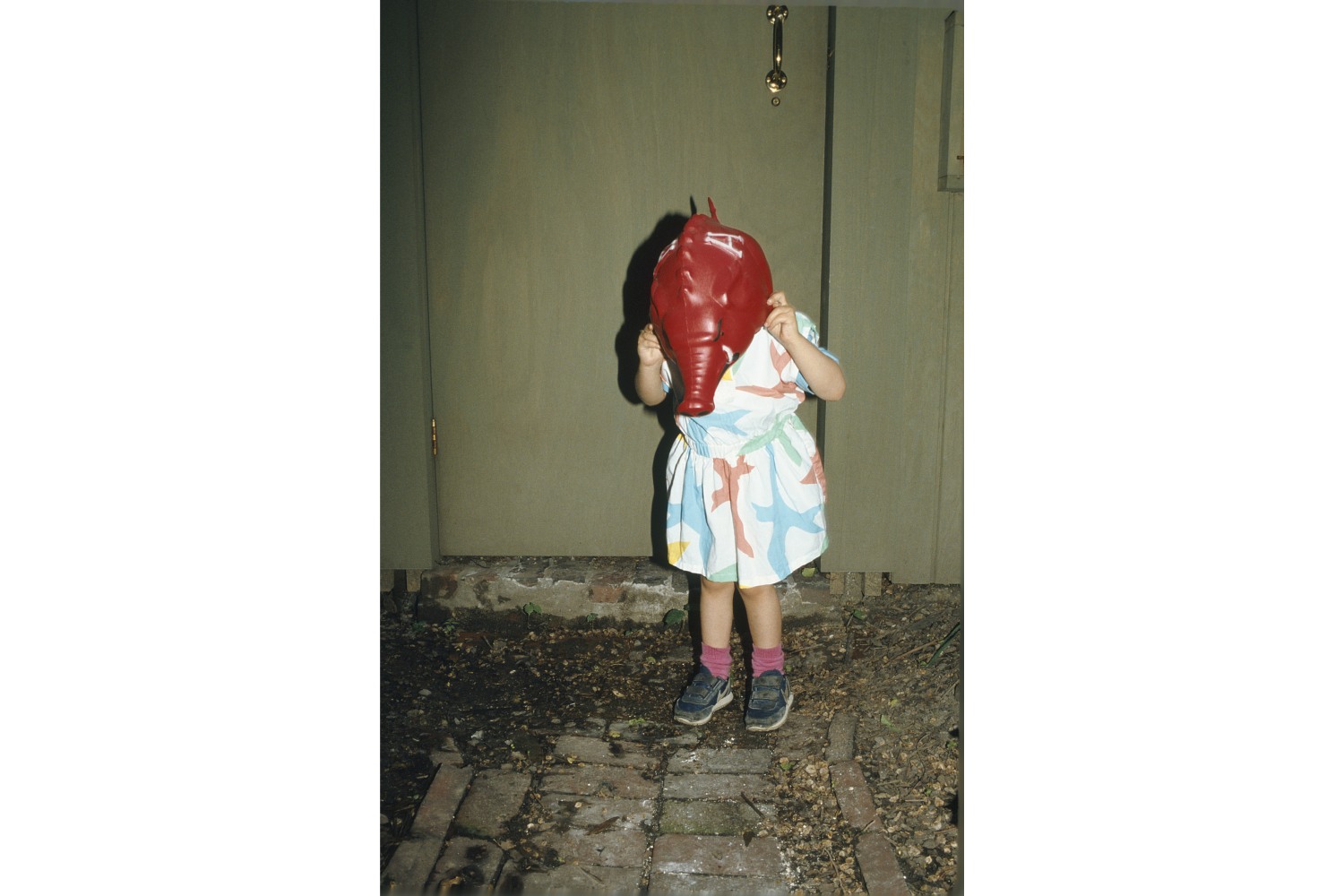

A friend of mine was slightly irked by what she described as an aesthetic akin to her “aunt’s family album PowerPoint presentations,” but on the contrary, I find Goldin’s format of choice to be strong both in its artistic intentionality and its genuineness. The familial vibe of the slideshow form successfully refuses the clinicality of institutionalism, but is not just a conceptual move: this really is the artist’s chosen family we’re seeing, the family she found when she left home at fourteen years old. These are her roommates, her godchildren, the sister she lost to suicide, the many, many friends she buried during the AIDS epidemic. These are weddings, birthdays, and funerals.

Loss is undeniably a prevalent theme, perhaps even the central motive in Goldin’s life and work, though we usually understand photography to be a medium of preservation. “I always thought that if I photographed anyone or anything enough, I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I’ve lost,” reads one wall text. A tension of trying to hold on and having to let go is present throughout “This Will Not End Well,” with its fleeting, unattainable images. The artist has asked her audience not to take any photos — to experience the work only here and now in this room full of familiar strangers, and to bring home nothing but the memory.