I learned of the Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila during the very first evening of my first visit to Beirut. Caught up in an adventurous roller coaster of business travel, I realized late in the day that it was my birthday, and so, eager to celebrate, I went to THE bar that all my friends had recommended. That night, overwhelmed by new friends and inebriated by the voluptuousness of the city’s nightlife, I just let myself go to the sights and sounds around me. Driving the car toward a last stop before sunrise, “Shim el Yasmine,” one of Mashrou’ Leila songs, played on someone’s iPod. It was somehow different from all the songs I had heard before that night: familiar and exotic at the same time. The song sealed my ongoing, unrequited crush on this city.

But don’t get me wrong. Despite this corny introduction, Beirut isn’t exactly a postcard destination: no one can ignore its violent history, the constant tensions between the city’s different communities, the shadows of ruins next to controversial construction sites that are drastically changing the identity of the landscape. A constant feeling of absurdity and precarity pervades everyday life here. Beirut is bleeding and healing at the same time, in a cycle of stress and energy that is fascinating to visitors.

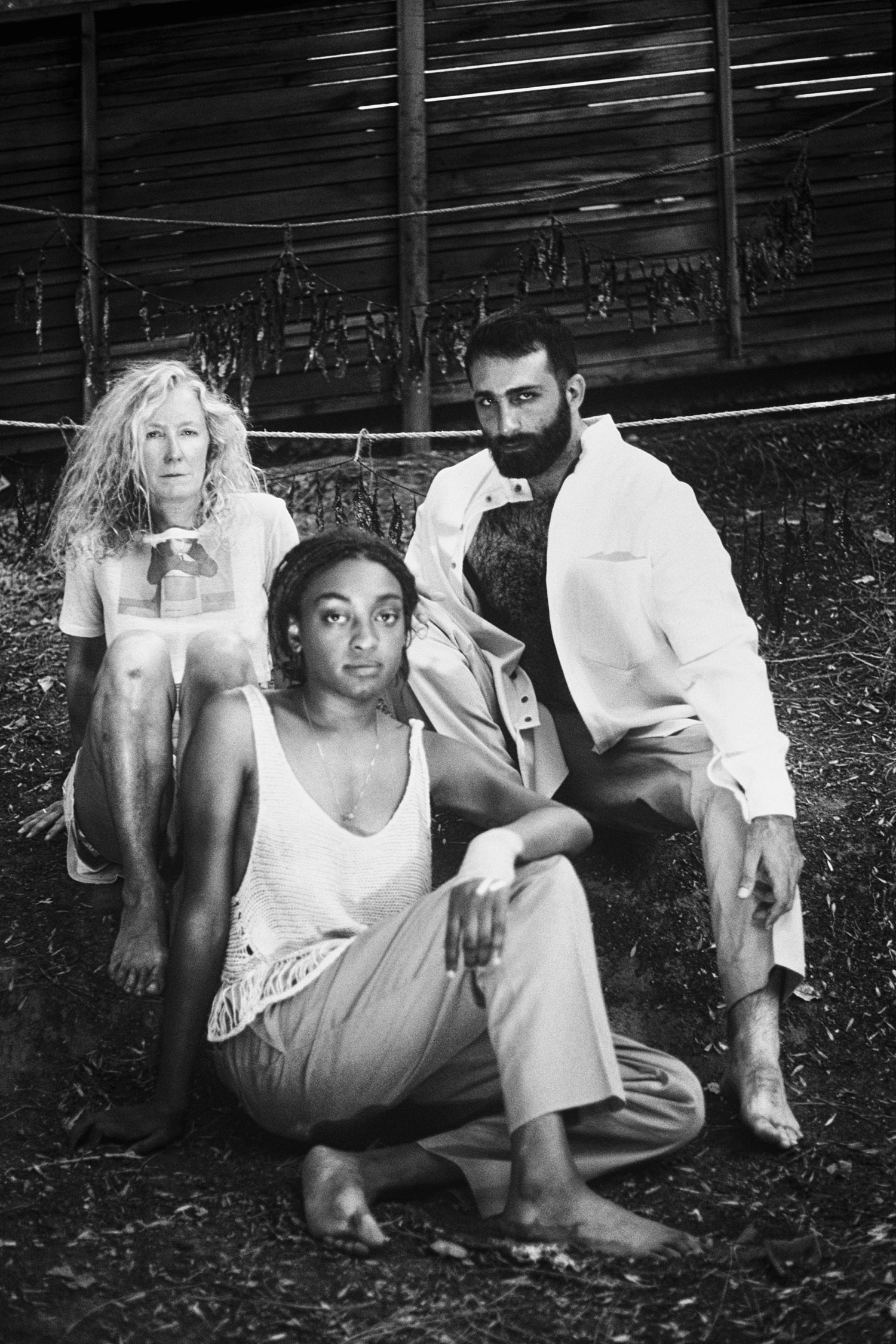

Mashrou’ Leila (the Arabic translation of “one night project” or “Leila’s project”) started in 2008; the band members met at the American University of Beirut, in the Architecture and Design Department, when violinist Haig Papazian, guitarist Andre Chedid and pianist Omaya Malaeb posted an open invitation to play music in order to create a musical workshop. Frustrated by the stress of the city, they intended to bring some relief to students. Soon the charismatic singer Hamed Sinno joined the group, followed over the years by drummer Carl Gerges, bassist Ibrahim Badr and guitarist Firas Abu-Fakher.

Thus did Mashrou’ Leila start their revolution. Until then and until them, Arabic pop music was mostly based on original refrains and traditional texts, on heterosexual, macho-dominated love stories in which sex is suggested but never unveiled.

Influenced by electropop, jazz, grunge and trip-hop, Mashrou’ Leila’s lyrics speak about a different kind of love. Although topics such as politics, lust and religion are addressed, there is nothing purely provocative about it: these feelings are expressed out of a long overdue cultural need. Only two years after the band was formed, late in 2010, the Arab Spring started and the Middle East witnessed unprecedented civil resistance in its fight for intellectual independence. For some, Mashrou’ Leila is one of the faces of this radical change, and not only for their controversial lyrical content but also because of their uniquely hybrid sound, never before heard in the region. Though often political, Hamed Sinno sings about more personal issues, avoiding the trope of a stigmatized kid in a war-torn country. His visceral, raspy voice soulfully expresses the struggle of a generation trying to live through change. The band built a faithful audience in the bars and pubs of Beirut. Then, supported by a powerful social network, word spread throughout the Middle East, from Egypt to Jordan.

Their first two albums were less than five years apart. Their third album, Raasuk, released in September 2014, was funded by fans through a Twitter announcement. Apparently, being a musician in Lebanon is not exactly like being a pop star in Europe or the USA; producing a cultural or artistic project is not easy. In order to protect their artistic integrity and avoid being manipulated for marketing purposes, Mashrou’ Leila decided to not sign on to a record label. The band takes care of pretty much everything, from the design of their album cover to the organization of their concerts, press and logistics. Incredibly close to each other, they run this operation with extreme passion and intensity, without any hint of greed for success and fame. It’s all real.

But, again, don’t get me wrong: in the same way that Beirut is not just a city where you can have a fun night, Mashrou’ Leila has important detractors as well as fans; the spread of their more insouciant yet political songs has not been welcomed by the establishment. (Some still remember the time that an important politician walked out in the middle of a concert.)

Today the band has reached a larger audience, and they regularly play in Europe. Attending one of their concerts in Paris or London is an interesting experience. You are part of a most diverse audience: young Middle-Eastern immigrants, hipsters, artists, intellectuals but also the queer community.

Over lunch with one of the members, he asked why I like Beirut so much. I wasn’t able to give a proper answer. But I think that Mashrou’ Leila have the answer, by being on the front line of a new generation of creators from the Middle East: they are witnessing a change, but they are also using the arts to foster progress toward a more open-minded society. Artists, poets, designers, filmmakers and musicians are able to develop their practices because of the bravery of those who broke through first.

So why shouldn’t we like Beirut? All I know is that on my next birthday I will be in Beirut again, and we will probably all be dancing to the music of Mashrou’ Leila.