Allan Sekula was long devoted to contemplating the open sea. Turbulent and wild, water can buoy a new global political and commercial ecosystem: past demarcations by colonialist interests have dissolved, and much of international maritime law remains to be written. The age-old profession of sailor, wandering ambassador, is untethered from any political system or state obligation; alternately, no system or state is responsible for the sailor.

Hesitant to romanticize these possibilities of liberation from dismal economic and national conditions, Sekula’s investigations into the true costs of travel and shipping have led him to the coastal edges of the world. Projects such as “Fish Story” (1989–95), comprised of photographs, texts and slides, probed the industrial ports of wealthy urban centers such as Rotterdam, Seoul and his hometown of Los Angeles for answers. The film essay The Forgotten Space (2010), the sequel to “Fish Story,” made with Nöel Burch, ventured even further by trailing the figures of this economy — factory workers, truck drivers and seafarers — who it is essential to grossly underpay in order to sustain this economy for large international trading corporations.

“Ship of Fools,” on view at Christopher Grimes in Los Angeles this summer, is Sekula’s 2010 body of work documenting the 1998 victory lap of the Global Mariner, the cargo vessel of the International Transport Workers Federation’s self-promotional exhibition, which inevitably became absorbed in the union controversy surrounding the black-market shipping systems operating under flags of convenience — the pipelines of transport that dodge maritime law by registering merchant ships in states whose policies are more advantageous and profitable than those of the ship owner’s, thereby sidestepping more rigorous labor and industry regulations. Lottery of the Sea (2006), the film work at the heart of “Ship of Fools,” is an uneasy, three-hour-long voyage from the open oceans to various points inland, with frequent stops and detours due to the ambiguities and large gaps in and downright absences of maritime law.

Protests and major environmental hazards, such as demonstrations against the impending US invasion of Iraq, serve as the occasional time stamp in the work. The film also shares the great length at which multinational corporations go to minimize media attention paid to the consequences of their missteps and gloss over the long-term consequences of their schemes. Local politicians and representatives at the site of a major oil spill on the coast of Spain turn away volunteers, telling them that the situation is under control, even while the sand is visibly black from a safe distance. In later scenes, we see vacationing groups and cruise-ship passengers photographing the entrances to trading ports of Panama as tourist attractions.

Anchored by Sekula’s rhetorical voiceovers — “What does it mean to be a maritime nation, to harvest the sea and rule the waves?” — and paraphrasing of Proust’s writings of the interpenetration between land and sea and Jules Verne’s 19th-century science-fiction novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the film is more video diary than journalistic documentary exposé. Explaining the etymology of the word agoraphobia — from the Greek agora, “open space,” a mental disorder causing one to perceive danger from wide, open spaces or vast crowds, seemingly contradictory conditions that can coexist in the overcrowded lower decks of a ship wafting in the center of the boundless sea — by way of opening the main narrative of the film in Agora, Athens, the artist begins his trek into the middle of the knotted maritime political tangle. Seafaring navigation is dictated by the clefts in sea colonization, the cracks resulting from centuries of carving up and recarving the global seascape. Dark insinuations flow through the film: we are told that Panama and Liberia are military pawns, countries created by the United States government; that Omar Torrijos, commander of the Panamanian and National Guard, died in a mysterious plane crash a mere three months after Ronald Reagan was sworn into office in 1981; we hear secondhand a debate between Sekula and a sailor that Islam inherently resists globalization, so this must be taken into account when negotiating trade agreements; he also apprehensively states that since 2001, the State’s War on Terror has given itself and its allies further unchecked liberties in the quest for pursuing oil in the name of truth and freedom.

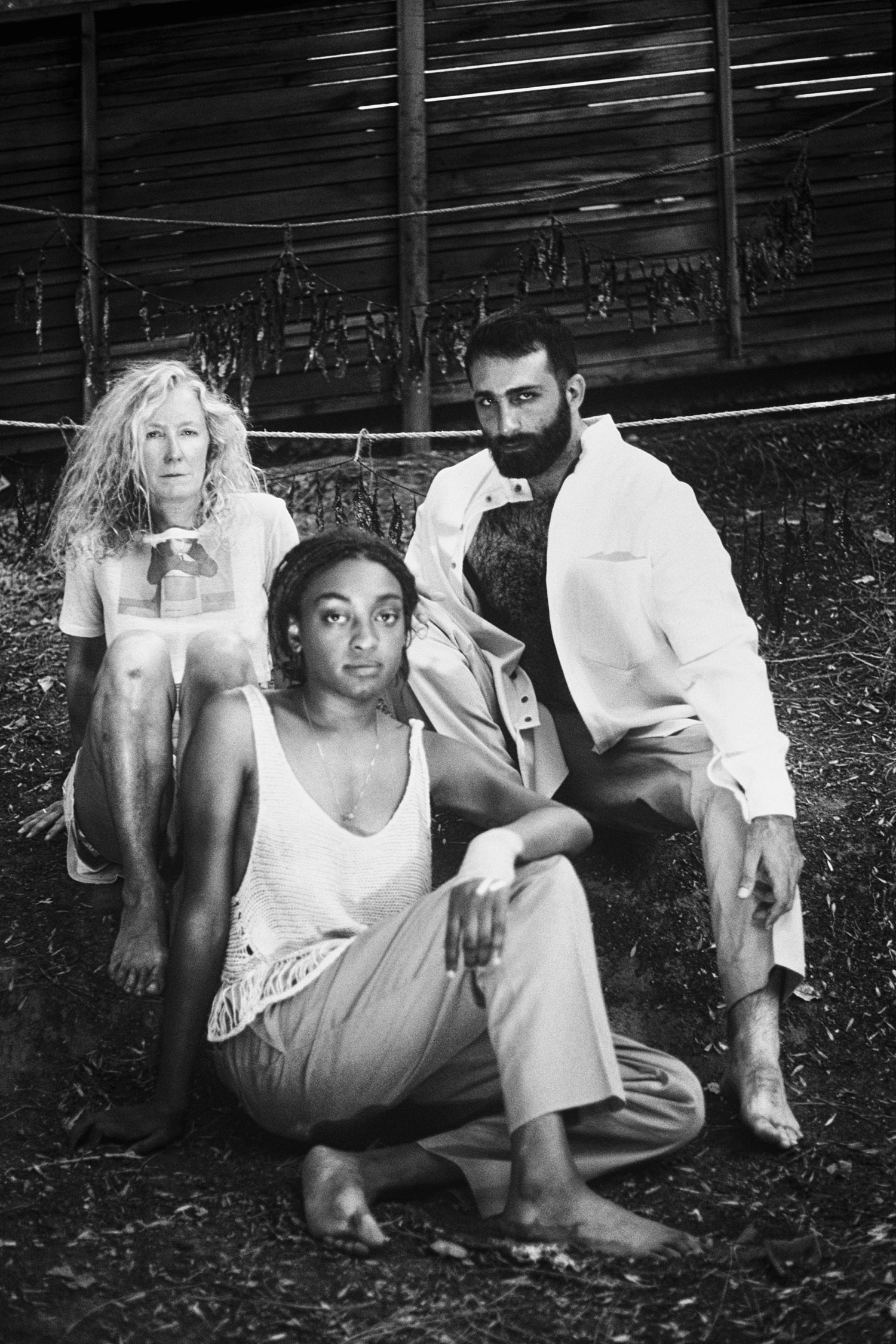

The presentation of the film further directs such critique as artistic approach, rather than bureaucratic investigation: debuting at the 2010 Bienal de São Paulo, the 4:3 aspect ratio of Lottery of the Sea,as opposed to the traditionally horizontally inclined feature-film aspect ratio of 16:9, appears nearly square in installation — best viewed in the traditional fine-art parameters of the box monitor, at home on a pedestal or floor. The film’s lingering, extended scenes are speculative, curious and not mechanical, as seen in the close range at which the camera pans over laborers securing each other’s hazmat suits with packing tape before disembarking to clean the newly oil-polluted beach, black slime sliding through the fingers of their gloves. Lengthy tracking shots of stacked modular shipping containers in a murky palette make for an easy visual metaphor for the anonymity and interchangeability of actors in this system. The first room of the gallery displays the oversized photographs of the exhibition in offbeat, broken arrangements. Glossy and saturated, these are mostly individual portraits of those featured in the film, as in Crew, pilot, and Russian girlfriend (Novorossisk) 1–10 (1999–2010); clouds and tide racing toward a sunrise vanishing point in Churn (1999–2010); and moon- and fluorescent-lit snaps of a ship’s exterior in Good ship bad ship (Limassol) 1–2 (1999–2010).

Lottery of the Sea is not the artist’s first documentary narrative; previous films and projects, such as “Fish Story,” Titanic’s Wake (2002) and The Forgotten Space dissect, in various intensity and precision, the very real effects of neoliberal policies and their resulting socioeconomic conditions. “Ship of Fools” was the last body of work Allan Sekula completed before his death in 2013. These somber, moving dossiers on the working conditions of marginalized laborers acting as international free agents pull out the poisonous ropes — loose under the water’s surface, under decks, shored up, inland, mainland, those buried in policy oversights and misdirected alliances — that wash ashore along with the Global Mariner.