Were someone to grab me by the collar and demand a definition of good documentary photography, I might offer the following: the best documentary photos are not those which seem to reveal truth. Instead, they are those which ensnare us in an active relationship to whatever is being shown (and, by definition, concealed). They reawaken us to life by staging mock encounters with the world, made uncanny by the photographer’s gift for timing, framing, and human contact.

A worthy example is Mary Ellen Mark’s Husband and Wife (1971), in which an Appalachian couple poses for the American photographer, who died in 2015 at the age of seventy-five. While the titular wife stands, staring into the camera, her husband crouches in the crook of a tree, pointing a pistol at her head as if he’s about to turn the photoshoot into a Weegee-style murder scene. At first glance, this image seems to show hideous misogyny. Except that it is the defiantly unconcerned woman who holds the photo’s power. Is she calling the old man’s bluff? Or is the couple surreptitiously mugging for the camera, trolling the city slicker photographer in a performance of the rural backwardness which they suspect she craves? The answer doesn’t matter. In drawing your mind into this murk of possibilities, the photograph has already succeeded.

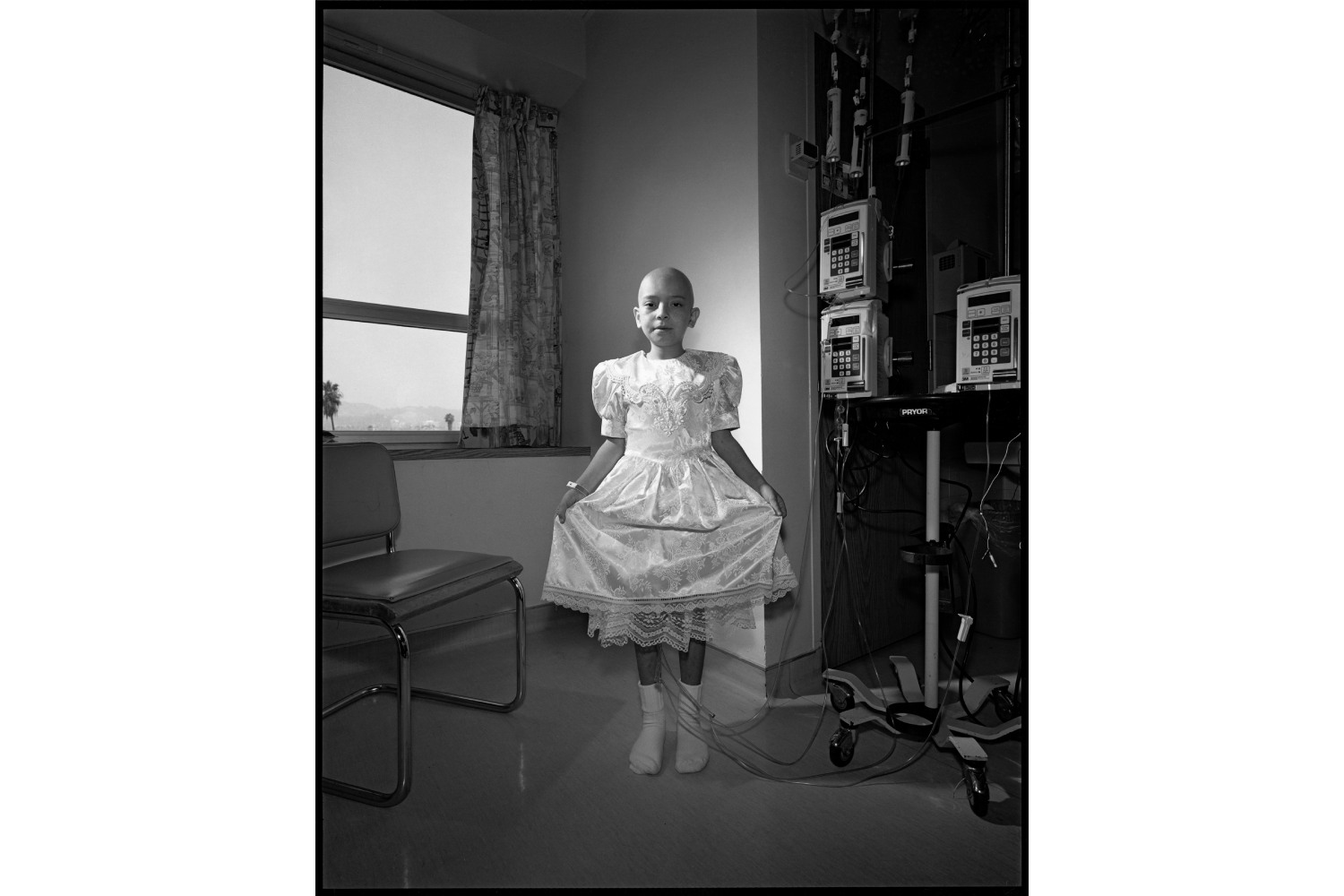

Husband and Wife is part of Mark’s understated and formidable retrospective at C/O Berlin. The show spans dozens of mostly black-and-white prints, divided into chapters focusing on communities and individuals. Mark’s subjects are often either marginalized — the drug addicted, the poor, the disabled — or external to societal norms in more malevolent ways: one 1986 series intimately portrays men, women, and children at the Aryan Nations Conference, in Idaho. Mark evades the high potential for fetishism that haunts all photographers who venture outside the mainstream, and the socially tolerable. These are images of great human significance, which arrest while resisting the urge to entertain.

It would be fair to ask if Mark’s subjects were always capable of consenting to their transformation into art, even while feeling grateful for the windows she opens onto life’s hidden corners. In 1978, she photographed the young Jeanette Alejandro, who was then fifteen and in labor. In Jeanette in labor, Cumberland Hospital, Alejandro, seeming very much a child, collapses against a hospital wall, presumably during a contraction. Her legs buckle and her face grimaces as she cradles her belly, which is obscured by a hospital gown. In Jeanette looks at her pregnant belly, the girl gazes downward at her enormous stomach, illuminated and bisected by a pregnancy line, as if wondering where it came from. Her hands fall outward, suggesting a desire to take flight. Evoking something angelic, the photo also stirs with the wrongness of a child’s pain. These conflicting effects complicate the flat, pitying tone that often attends discussions of teen pregnancy.

In 1976 Mark spent thirty-six days as a journalist in the high-security psychiatric wing of Oregon State Hospital. The resultant work elicits sympathy, curiosity, and horror — a humanizing elixir that, in my case at least, opened tear ducts. In Women dancing to records (1976) the normalcy of four women just being women — embracing, dancing, and smoking — fights against the barbarism of their entrapment, which is emphasized by the antiseptic tiled floor and a large window striated with shatterproof wire. I wanted to know more: about these people’s minds, and about a society capable of producing such scenes in the first place. That desire reflects Mark’s ability to make us think, tenderly.