Recall those nectarine swathes basking in abeyance. Quenching, their tipped menisci urge semantic gushing. Coralline registrations: scores of quince, milky auburn, and contused puce. Metastatic interactions are soda-sibilant with ashy effervescence and smattered albescent. The jellied bravura of spasmodic flares has shuddered into purposeful, muscular pools. Horizons of amaranthine gradate, leech to some other caramelized luster. Overspilled: at turns, this surface expressivity dissevers into instants of a strangely mellow peel. In seared curls and flakes, the sheet denatures itself in a rose erosion. Memory, a hole of duration, is where loss and presence are mutually reliant.

Unchambered, ulcerative, and coreless, Lotus L. Kang’s draperies of photo emulsion paper are surface perpetually in process. Prone to light, atmosphere, and humidity — expressed in a catalogue of tints and fitful pressures — their generative reactions proliferate poetries of change. Being vulnerable occasions thinking of what is inside a moment, a hole, which poetry restores in us. Such a process echoes Trinh T. Minh-ha’s conception of “speaking nearby” as opposed to “speaking about,” a manner of speaking that reflects on itself and rests in intimate adjacency to its subject. “A speaking in brief, whose closures are only moments of transition opening up to other possible moments of transition — these are forms of indirectness well understood by anyone in tune with poetic language.”1 Opening up a sense of becoming entails the vulnerable and volatile energies themselves, often interleaved. Such animations are seen in Kang’s work on being, where her nonlinear making, material misuse, and private enactments invoke analogies to bodies and ecologies in states of transition and thus bared to unpredictable change. While responsive to the dynamisms of biology, epigenetics, and familial histories, Kang’s incorporation of theories and speculative fiction is similarly metabolous, a process of “regurgitation.” “My work exists in literal and metaphoric states of becoming and unfixity,” Kang says, “and this deconstructive strategy aims to continually build, break down, and rebuild.” Infecting and inflecting, Kang’s forms of latency refer to the world around them while having, in their flex and trace, a life of their own.

Timelines bend and dilate in these films — installed in many configurations, but foremost addressed here in “In Cascades” at Chisenhale, London (2023)2 — which swim in the space between representation and embodiment, where much of Kang’s work is oriented. In writing, I can only engage with these waterfalls as afterimages, their discontinuity provoking tributaries of thought that evaporate into ripe cloudbursts of observance. Petrichor. Naturally, the mind rewrites these papers to meet desires and projections seen in its flushed, unguent mirror. Condensations of time, the “Membranes” (2017–ongoing) precede me and are yet with the world as much as myself. In the sun’s excretory light, these unrolled pendants chronicle space, atmosphere, and persons with the receptivity and organicity of an ineffable lifeform. Sensitivity, assured. They are image-body respondents of indefinite lability, to which peripheries enigmatically stick. Permeabilities of life are registered with sensuousness — as though iridized by debris, worms, spores, corpuscles, bacteria — these “Membranes” cross temporal registers and, in doing so, transgress the border between body and world, becoming somehow kin to both. As with time, so these “Membranes” ruche space, creating pleated niches where energies reverb.

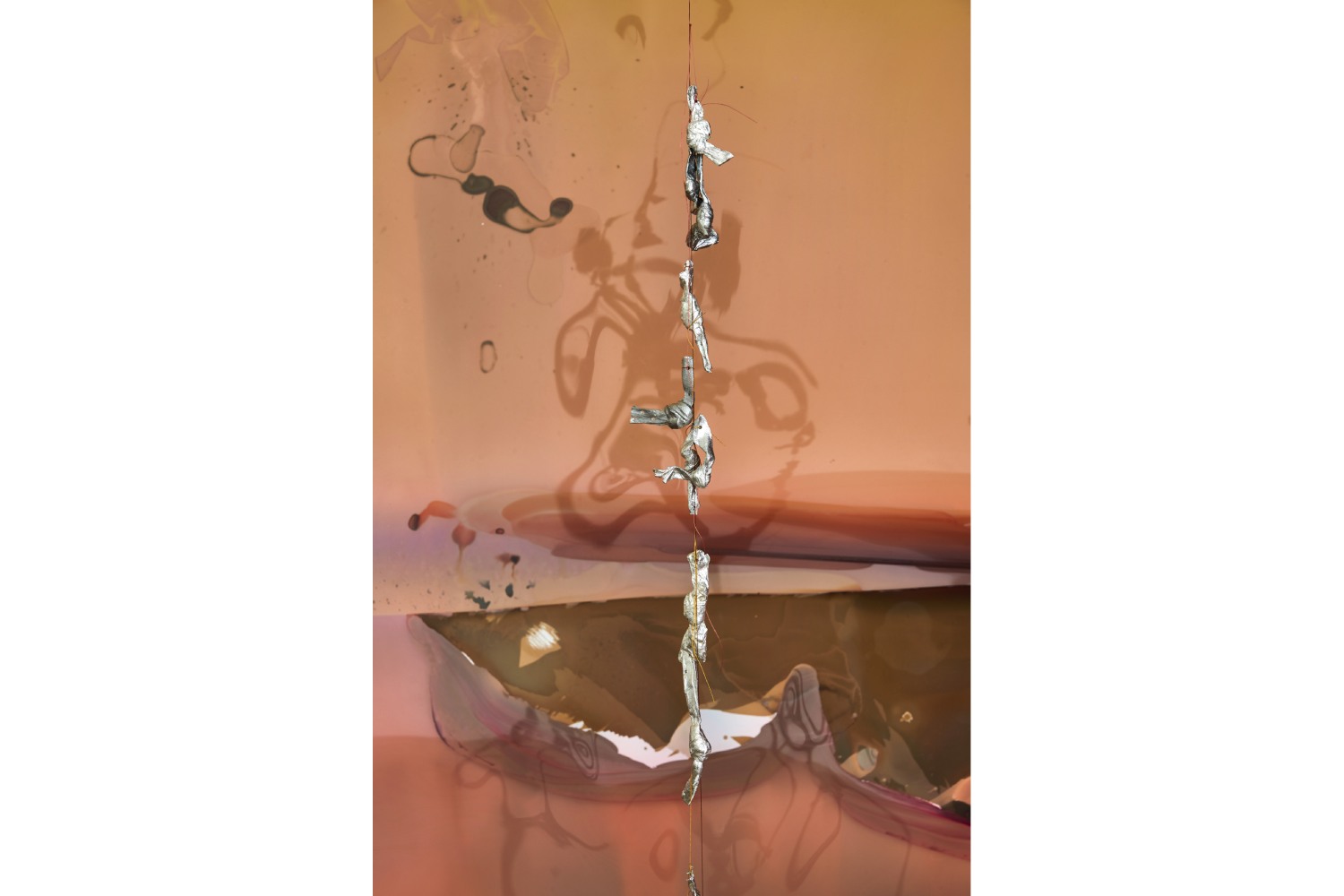

Others are isolated to cohere exit-entrances from which passages are relaxed and casually treaded. Sleepy peach stone cavities and embryonal hollows, bodies among this equally flexuous space make a sense of interiority extrusive and malleable. The composition is suspended from an exposed infrastructure using Super Joist material, which was created collaboratively by Kang and architect David Andrew Tasman. With its framework centered, the structure most palpably demarcates an outline, and yet its very strength is realized in a series of annular voids that fortify its capacity to hold. It bears a similar logic to the lotus root — peppered throughout Kang’s practice in sand-cast aluminum, the slices preserving its soppy ecology and mangled constitution, now slotted into doorways (Lotus, 2023) or threaded as wind chimes (Origin Gate, 2021). Kang applies the casting technique to many edibles, which privileges the disinterred impression created from the source matter. From the sand a husk of metallized loam, its pewter-sugar a relic animation — energies mottling its infinitesimal extremities like the work of woolly aphids. In the dank concatenations of this mudmarbled lotus root, the porose flesh is thickly rhizomatic and made selfreferential for Kang as a familiarity: “It’s a form that feels embedded within me, my psyche, my body, my physicality.” 3 In the nutritive elements of Kang’s practice is the umami of relations, embraced in an irresolvable stir. Striations of the soggy, the fibrous, the elastic, the compact, the slippery, here sprouted, desiccated, laced, pressed, made speakable and scriptural. Of what? The riotous roux of becoming, energies of transmigration, and invocations of familial pasts. Inheritances of flavors incant a spell. Names smoothed over the tongue; the familiarity of palates a sea-polished stone. Trajectories misaligned spiral inward in prolonged processes of pickling, poaching, and fermenting. Asian pear, kelp knots, mung beans, sesame seeds, anchovies, ginseng, hibiscus, cabbage, and perilla leaves — this is food as filiation.

Upon the floor among the “Membranes” are a series of tatami mats, “Receiver Transmitter” (all 2023). Each is compiled as though a bodily technology composed of leaves, folds, and layers. The tatami honors a connection for Kang: “The mats came from a small historical detail I’ve held onto. My grandmother, the grain and seed shopkeeper, would also sleep in her shop in order to make enough to provide for her family.” 4 Described by Kang as “a woman of vessels, seeds and grains,” her paternal grandmother owned a modest shop located in Seoul, where she settled after fleeing North Korea before the war. Modular and portable, the tatami brocades a comma in space, in which to curl and recharge as much as to simply go on. In Receiver Transmitter (Viola Mandshurica), the mat is folded and adorned with the arborescent husk of a cast aluminum cabbage leaf and an inky eidetic notation of the eponymous flower. Together, they are wrapped in a pigmented silicone sheath grappled at one end, upon which talismanic nourishment is gifted in three tangerines cradled in tissue paper. A scoliotic curve of cast aluminum intervertebral discs is interspersed with similarly cast lotus root and shiitake in Receiver Transmitter (Intervertebral). Joined as silvered pulses, the discs are the glutinous non-space that keeps the vertebrae together-asapart. In these attentions to the interstice, Kang’s tatami are interdimensional conjurations, unnerving the aspic of inheritances to rejuvenate them as restoratively conductive. The irregular way of this electric “S” becomes, upon the tatami, a resonant gauze through which a rested, alienated, exhausted, or displaced body passes through. Following the stroke of sibilance, a call between two ghosts. Together, Kang’s installation convoked madang, the inner courtyards traditional to Korean architectures, yet in this respirational cloister interiority and exteriority debouch one another in vibratile osmosis — the warming distension of space accomplished by the fulfillment of emptiness.

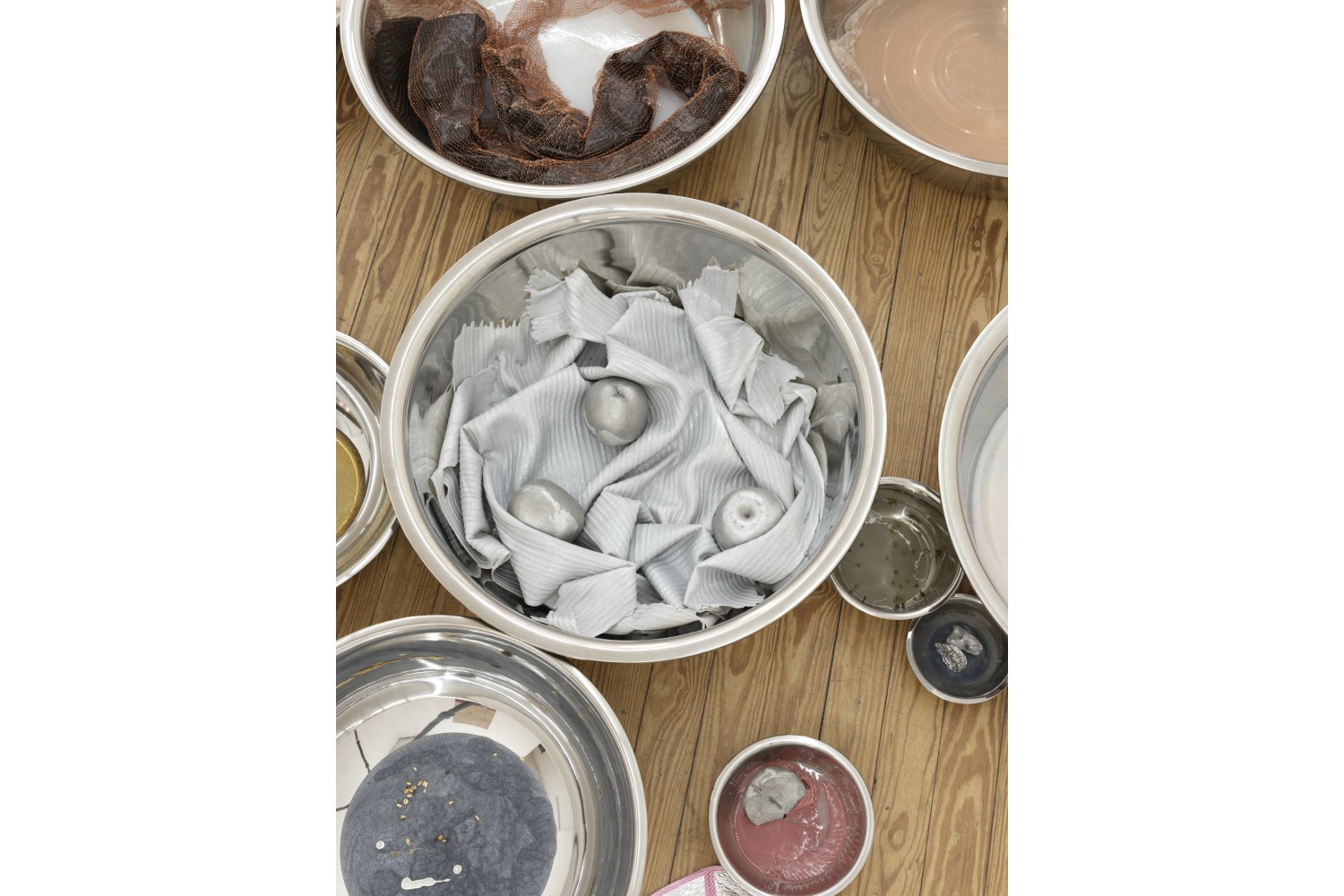

In Mother’s (2019–ongoing) archipelago are glinting steel basins that puddle as though self-replicating cells, yet their glistering wells are ladled with variants both sterile and contaminating. Fingered whirlpools, capillary waves, matters loosened and liberated in the well’s swirl: paludal silicone; cordyceps fungus; peach pit; lotus seed; copper garden mesh; mung beans; dried fish bladder; dried magnolia flowers; water! Pellucid droplets upon the ground, one imagines their contents might slip and converge with the slightest jolt. Peeking into their open globes, plastic slicks mingle among the frittered tadpoles of cast anchovies. Pears nested whole among eel-shaped folds or halved and clotted in ruddy emulsion. Fecal resemblances crumple in fruit packaging nets. The coital twining of Chinese fungus is amplified by the reflective canisters in which they are held. These vivaria are ecosystems of libidinal repulsion — odes and baits, bounties and hatchings — depleting the boundary of self and matter and sensing the meshing of desire and abjection.

Kang’s attention to light as a parasitical agent and medium dislodges conceptions of the ornamental. Here, Kang speaks nearby the hermeneutics of surfaces and the ontological ambiguities of shine, as analyzed by Anne Anlin Cheng. In Ornamentalism (2019), Cheng theorizes the yellow woman (offered as “a conceptual category and a critical agent”) 5 as ornamentalized object-person, figuring a form of “interstitial life.” This “perihumanity” is “produced out of synthetic accretions that challenge the very division between the living and the nonliving.” 6 This ornamentality of Asiatic femininity brings a body that is “thickly encrusted” with “a phantasmic corporeal syntax” 7 signaling agencies as surrogacies within the politics of specularity. Cheng’s extension of the historiography of raced bodies situates the aesthetic being of the yellow woman as an intractable intimacy between being a person and being a thing, an intimacy that troubles the notions of agency, ontology, and racial embodiment. If ornament is the historic enfleshment of Asiatic femininity, Kang irrupts the constructive implication of objecthood into a deconstructive subjectivity, where excess assumes complexity and scale. This shift is a grasping of what constitutes being at the interface of ontology and objectivity.

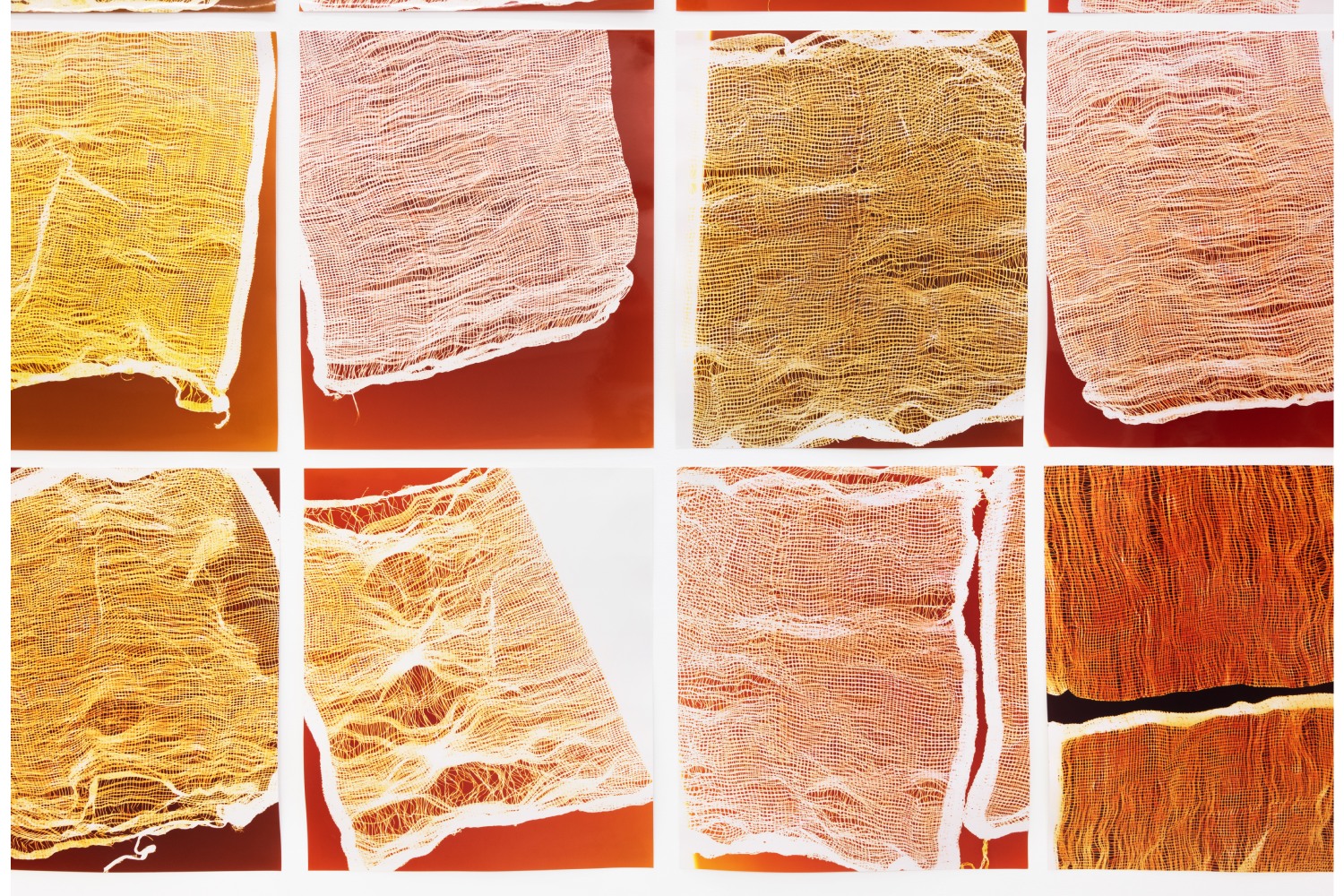

As non-neutral entities, Kang’s vessels are holders, carriers, and containers constituted less from protecting than sharing and gathering — receiving from outside and metabolizing from within. Mother’s sheen reflects the body that observes, implicated in its concave lens of intelligent slurries and alchemical anatomies. As with the lotus root, looped through these chemical, chromatic, and industrial blendings is an umbilical calm. For the exhibition “Her Own Devices” (2020) at Franz Kaka, Toronto, shavings of onion husks populate the gallery floor, cradling sand and silicone. These Glean (2020) are geminal exposures whose dead-skinned leaves are carriers all the same. If only re-fleshed, they might have occupied the eponymous gauzy sacs seen as a mosaic of thirty-five photograms. Tiled, they are a shriveled gossamer corpus, fibers lost to stringy filaments — prehensile hairs in search of touch — with genealogies expressed in crisp threads and frangible fray. In the light of the photogram, the sacs lose the stagnancy of category.

The sculptural dissidence created by acts of scattering and dispersal intensifies the sensation of non-singularity, summoning the pupal, the seedling, and the germinal as if space were an incubator without an inside. In Bloom (2019), canisters of cordyceps fungus are harbored by pullulations of feculent clay forms; variants of Mother, they are grumous, needy molasses. While not slimy per se, the schema of the clotty and sticky squirms here, a substance of undeniable projection: “The slimy does not symbolize any psychic attitude a priori; it manifests a certain relation of being with itself and this relation has originally a psychic quality […] because the sliminess has returned my image to me.” 8 As with Bloom, Kang’s loose collections of forms are states of hypersensitivity that, in their phlegmy adherence, catalyze attentiveness to one’s attention. Percolating in fissures, the viscous reshuffles relations to space and resurfaces a potential meaning of being. It shares a kinship with the hole from which it might arise the elusive locus that resists picturing. As though excreta of space, about the innermost edges of “In Cascades” are Kang’s rat pups formed of translucent urine yellow or pustular orange glass. They are licked in sticky circumstances: as migratory and parasitical species, they are also case studies to better understand humanity, another fleshly refractor.

“A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing. All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.” 9 Even in dormancy, difference spreads. Channels offer ritual channeling. Inherited knowledge of the seed is seeded in the body that ingests. In Fleshing Out the Ghost (2023), Kang created a photographic series during a thirty-eightminute performance on her thirty-eighth birthday, the age of her grandmother when she fled North Korea. Her studio debris of these tangerines, lotus joist holes, image-bodies, and tatami are transitions of standing and laying. Stilled, she looks toward the ceiling and is then lost to a blurry crawl. Somatic poetries are enacted in these staggered movements of communion, where origins, memory, and partial possession are porous. In these photographs, Kang’s thirty-eight-cycle massages time to extrude interiority as ritual, a loophole communing present and past. Enfolded histories of cycles are likewise enfolded in this cycle: the photographs stashed within the tatami of her “Receiver Transmitter”. The tatami, now a trove of intervertebral treasures, slipped within. Kang’s work is perhaps one most intimately suited to the amorphicity of replenishing, a locus of capaciousness where feeling precedes — and might still be untouched by — conditions of knowing. At first blush: the convulsion of becoming.