When Michael Fried published his notorious essay “Art and Objecthood” (1967), he likely did not expect “theatricality” to become such a relevant concept in the aesthetic debates on experimental theater, visual art, and performance. Although the term was used to condemn minimalist sculpture for depending on the spectator’s presence, thus not being self- sufficient, Fried indirectly admitted that what constitutes the aesthetic value of an artwork is essentially the interrelational connection between the beholder and the art object.

MAMCO’s exhibition dedicated to Jackie Winsor, bringing together some of her most important works from the 1960s through the 2000s, evokes the American critic’s unintended lesson on aesthetics. Moving around the sculptures that the post-Minimalist artist executed through meticulous craftsmanship and research on material, shape, and process, the first impression is that they inhabit their space and confront spectators. As living bodies in a dormant state, these anthropomorphic presences radiate energy and ask for proximity. They invite the viewer to approach and linger on their story — to perceive the time and work needed for their completion. Temporality is, thus, an intrinsic property of these objects, since the duration of perception corresponds to the time of realization of the work. The viewer’s object of attention is not the form per se but what is within it, the processual condition and variable circumstances that led to the sculpture’s fulfilment.

Rope Trick (1968), Dark Vertical Cylinder (1969), Double Bound Circle (1971), Rope Arch (1968), and Bound Grid (1971–72) are the sculptures on display that most suggest this sense of presence and aesthetic interaction between the work and the viewer. They are some of the iconic works that Winsor realized from 1967 to 1971 in her studio on Mulberry Street in Lower Manhattan, using heavy secondhand rope, first covered with resin, then wound around itself. In Dark Vertical Cylinder, the thick maritime rope twisted upright becomes a totemic cylindrical body. The human scale — about two meters tall and thirty centimeters in diameter — and the plasticity of the rope’s ridges lend the work an anthropomorphic appearance. But beyond its mighty aspect, the object imposes itself as a performative remnant: by following the irregularities of this very long thread that defies gravity, the viewer’s gaze reenacts the movements, the sound of the rope moving on the floor, the artist’s labored breathing while grappling with the thick cord’s physicality.

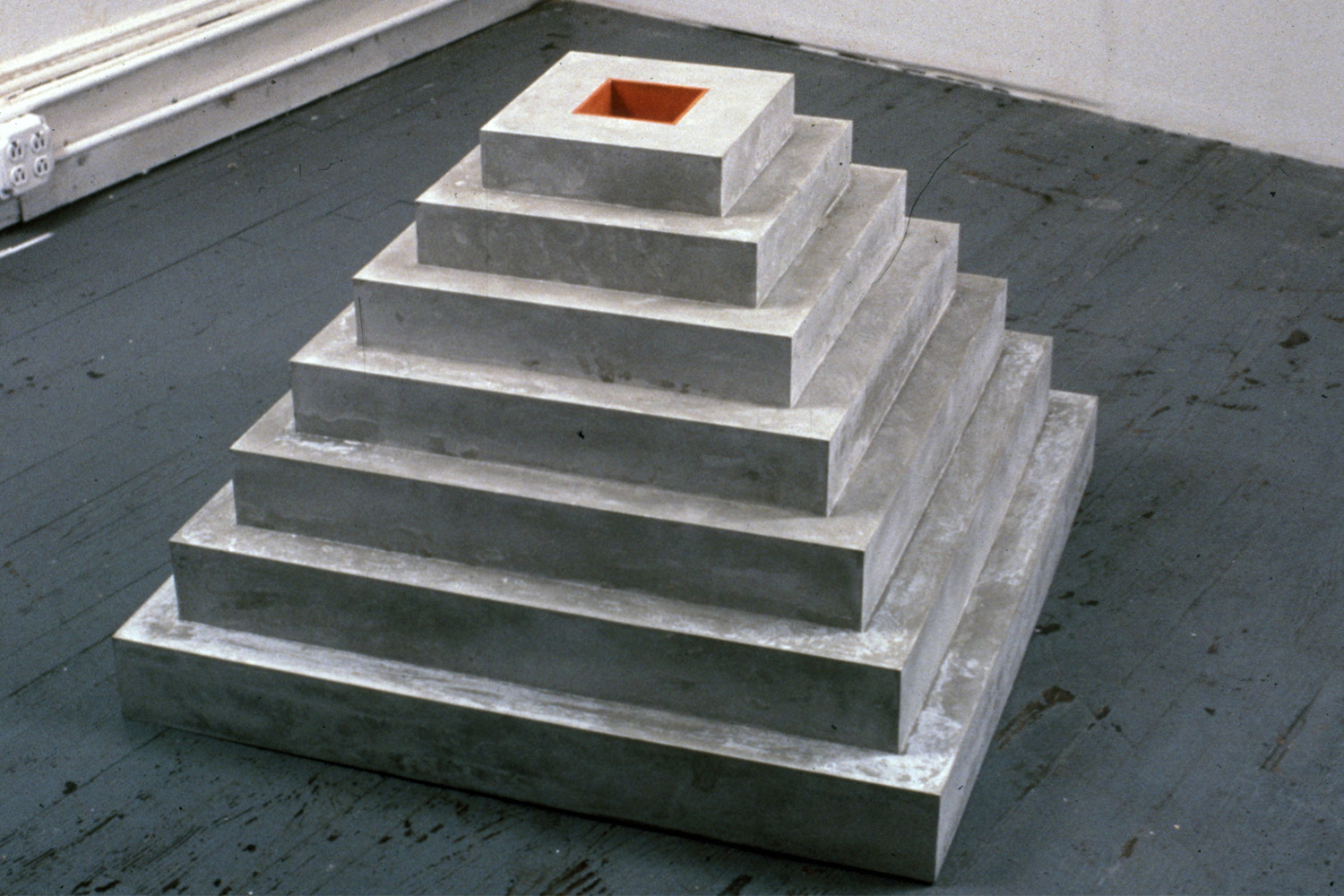

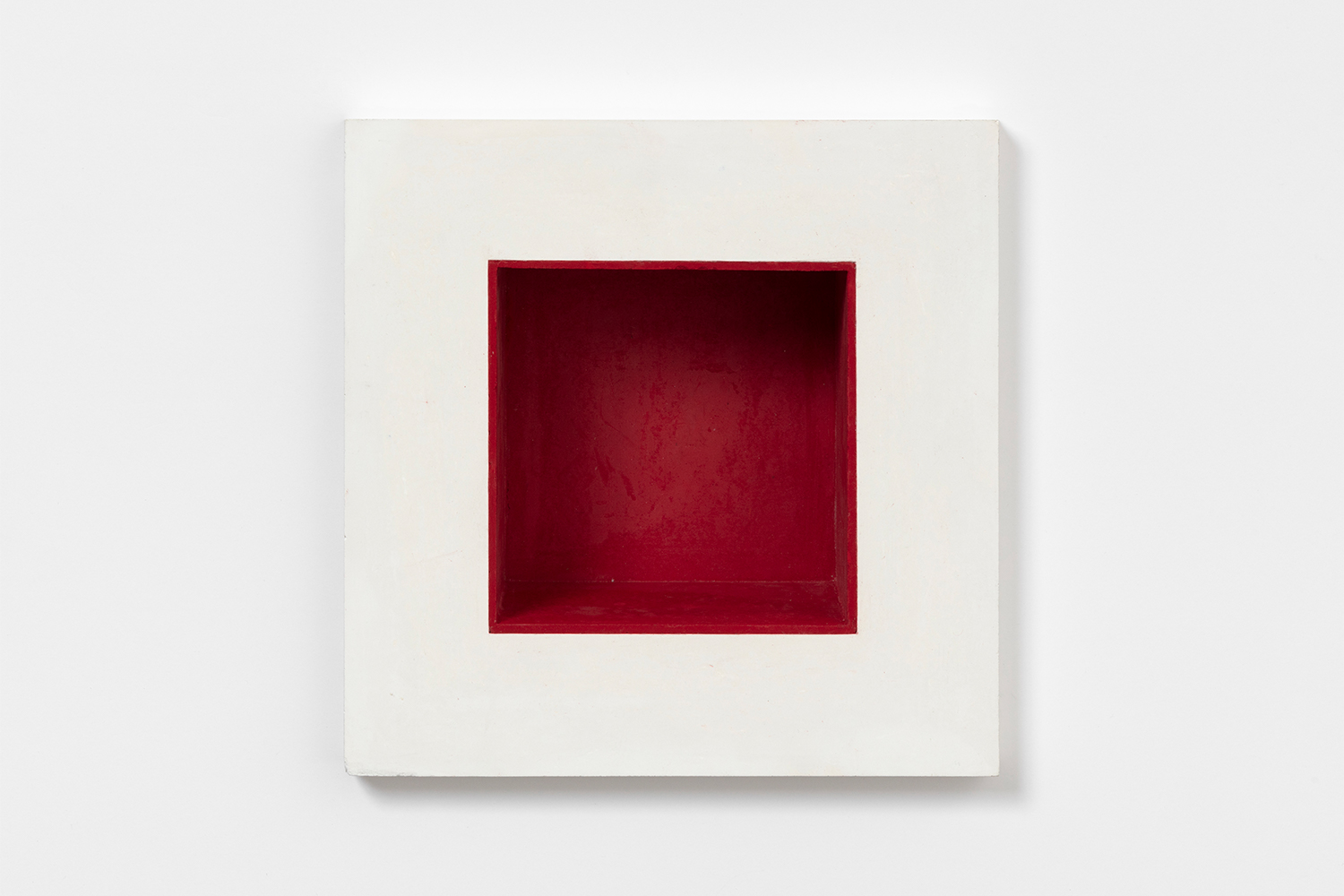

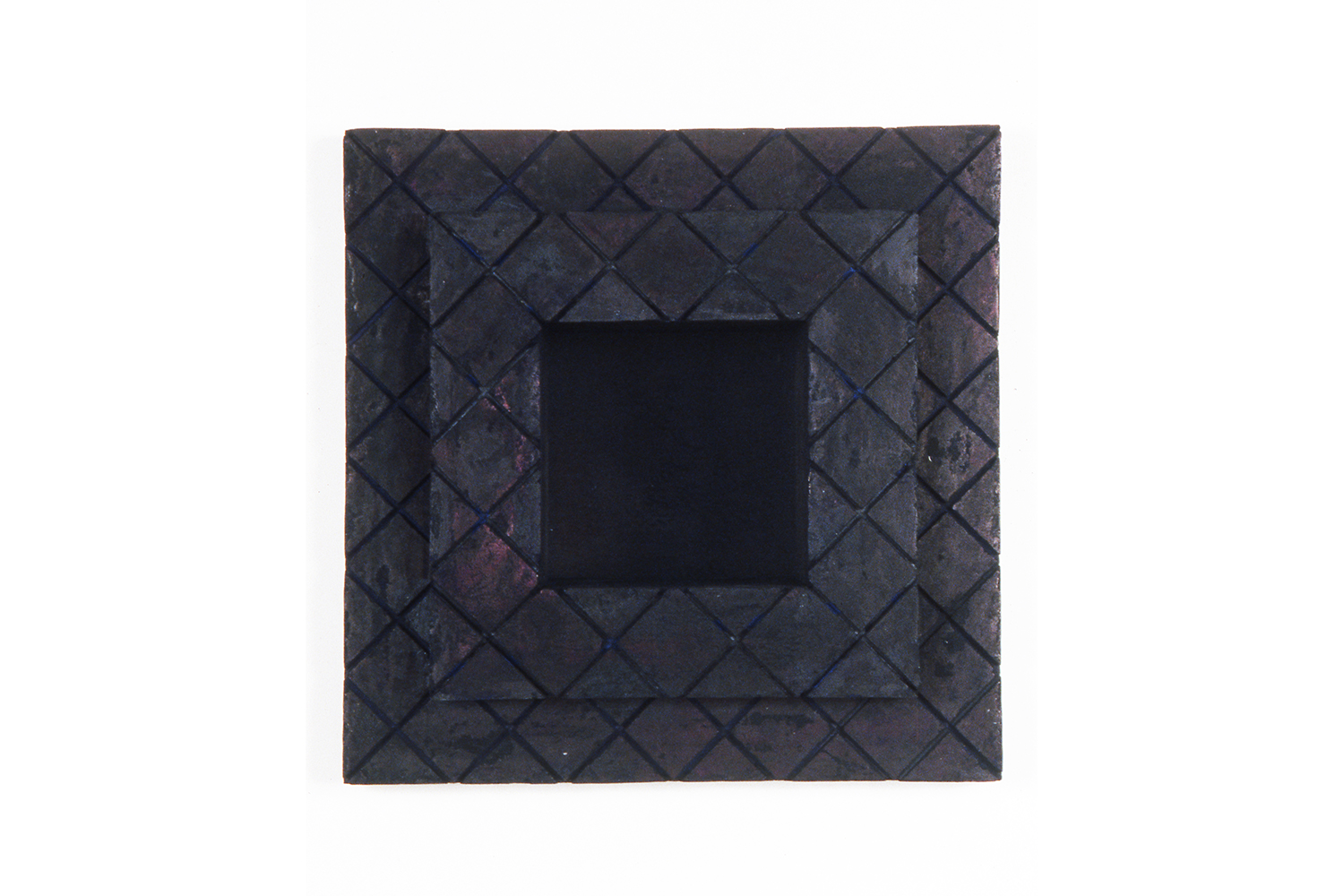

For Winsor, the act of realizing a sculpture is no different from the making of a performance. Indeed, her laborious, repetitive, task-oriented methods are similar to Yvonne Rainer’s radical approach to image-making through improvisation and everyday actions. Winsor not only saw all of Rainer’s performances, but also felt a particular affinity for her revolutionary method of energy distribution. Indeed, the dancer’s influence is perceptible in how Winsor’s sculptures are choreographed in space. Although they are all self-contained objects, independent from each other, a dynamic tension arises from their spatial arrangement. The spin movement of Solid Lattice (1970) is mitigated by the gridded network of tree branches of Bound Grid (1972). On the other hand, Pink and Blue Piece (1985) almost disappears as its mirrored sides — each with a small square opening in its center — reflect the surrounding environment, the other objects in the space, and the viewer. This interplay of opposing but complementary forces is exemplified by the “Inset Wall Pieces” that the artist began in 1998. These objects, oscillating between paintings and sculptures, invite the viewer’s gaze to go beyond the layers of paint, wood, or cast concrete and penetrate their dense, optically pulsating centers.

These sculptures show Winsor’s relentless search for an interactive dialogue between the work of art and the viewing process. They prove that Fried was right, despite his overall negative evaluation: an object becomes aesthetic through the process of experience; the viewer’s gaze extends the artwork’s material configuration, going beyond simple physical matter.