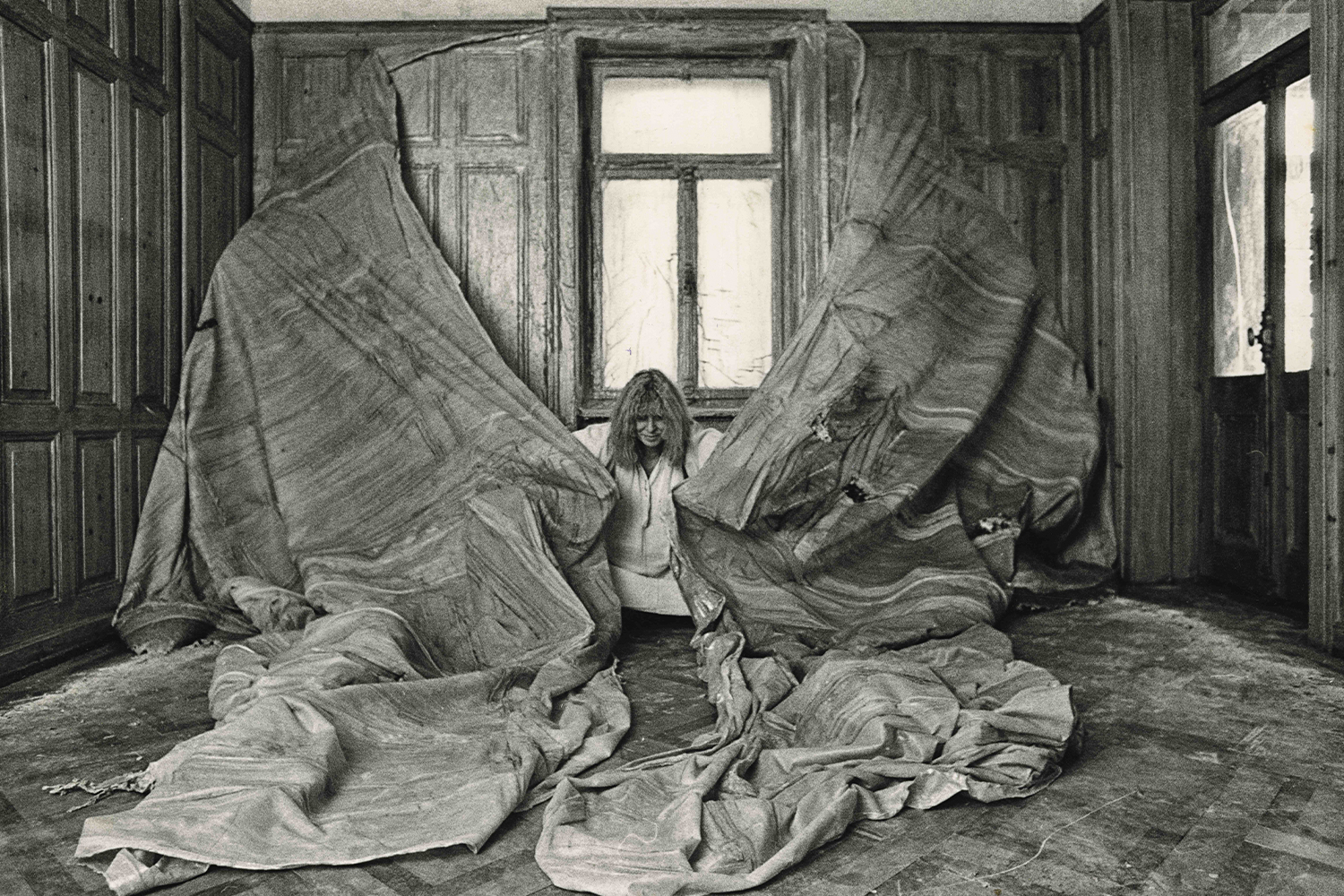

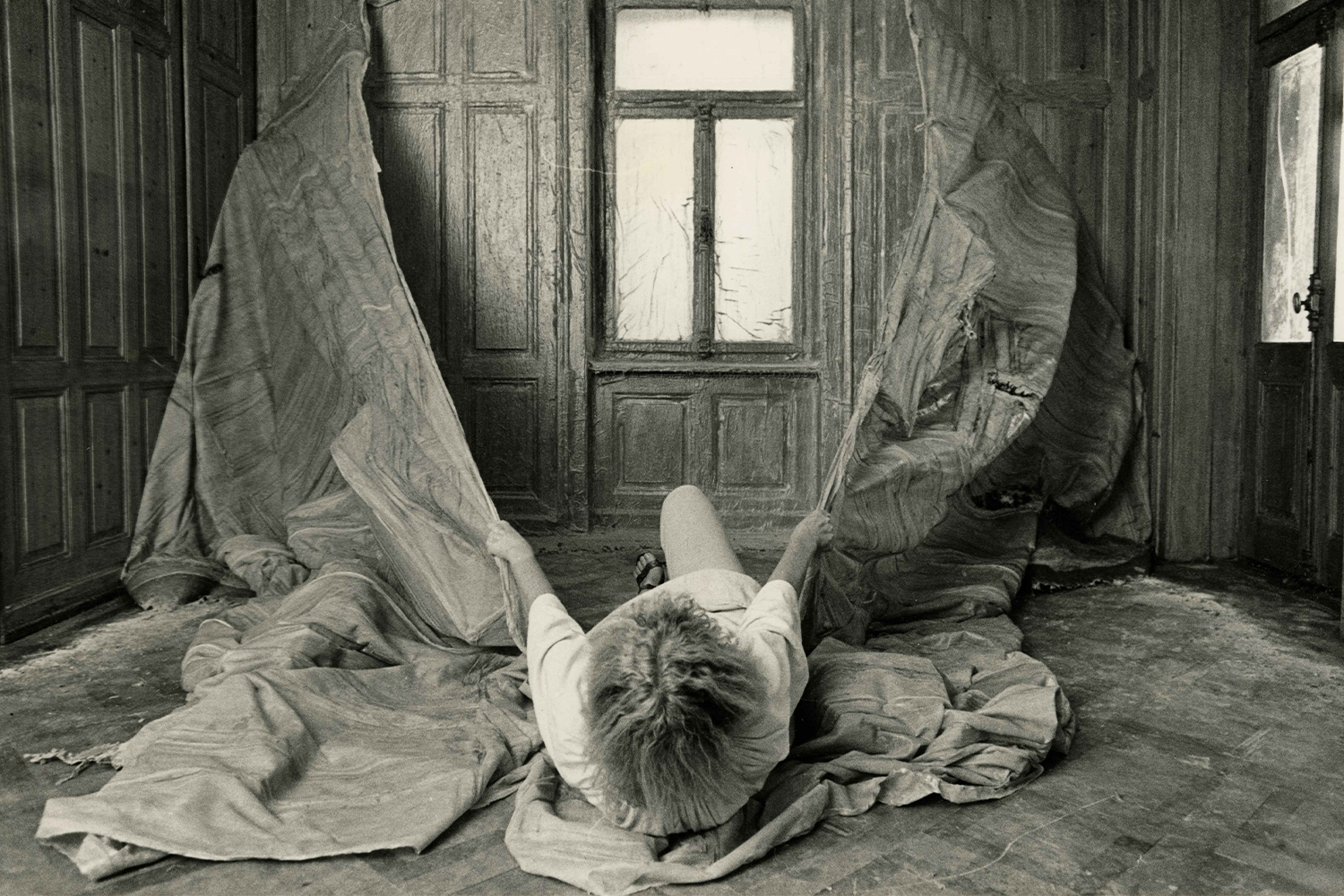

When the word skin is verbalized — to skin — the associations with this outer layer of the body start sounding sinister at best and downright repulsive at worst; the activities of horror icons Buffalo Bill and Leatherface are just two examples of this gruesome act having permeated public consciousness. But when can skinning become a gesture of working through something that was previously repressed? The technique of “skinning” (Häutung), developed by Swiss artist Heidi Bucher in the 1970s, consisted of applying gauze and fish glue to the surfaces of houses, interiors, doors, and other architectural elements, and coating them with liquid latex.1 With great physical effort, the dried coatings were then peeled from the walls and floors, and what was once a private space was suddenly under the scrutiny of the many. Bourgeois domesticity imploded, so to speak.

These fleshy sheets, arguably the artist’s best-known and also most perversely fascinating objects, are currently on view in the retrospective “Metamorphoses I” at Kunstmuseum Bern, a collaboration with Haus der Kunst and Muzeum Susch. In the exhibition’s entrance area hangs Herrenzimmer (1978), a skinning of a gentleman’s study, a sacred space formerly reserved for the male members of the family, that was located in the vacant villa of Bucher’s late parents. The uneven surfaces of latex act as a receptacle for the suffocating traces of history; it is as if the artist infected the architecture and appropriated it for her own use, impregnating the study room with desire and frustration. The epistemic monopoly of pater familias suddenly seems weak, almost pathetic. It is a fundamentally feminist gesture in the sense that it exposes the highly gendered nature of the supposed neutrality of knowledge, which becomes hollow from within, easily replicable, inverted, and temporarily embodied by someone else.

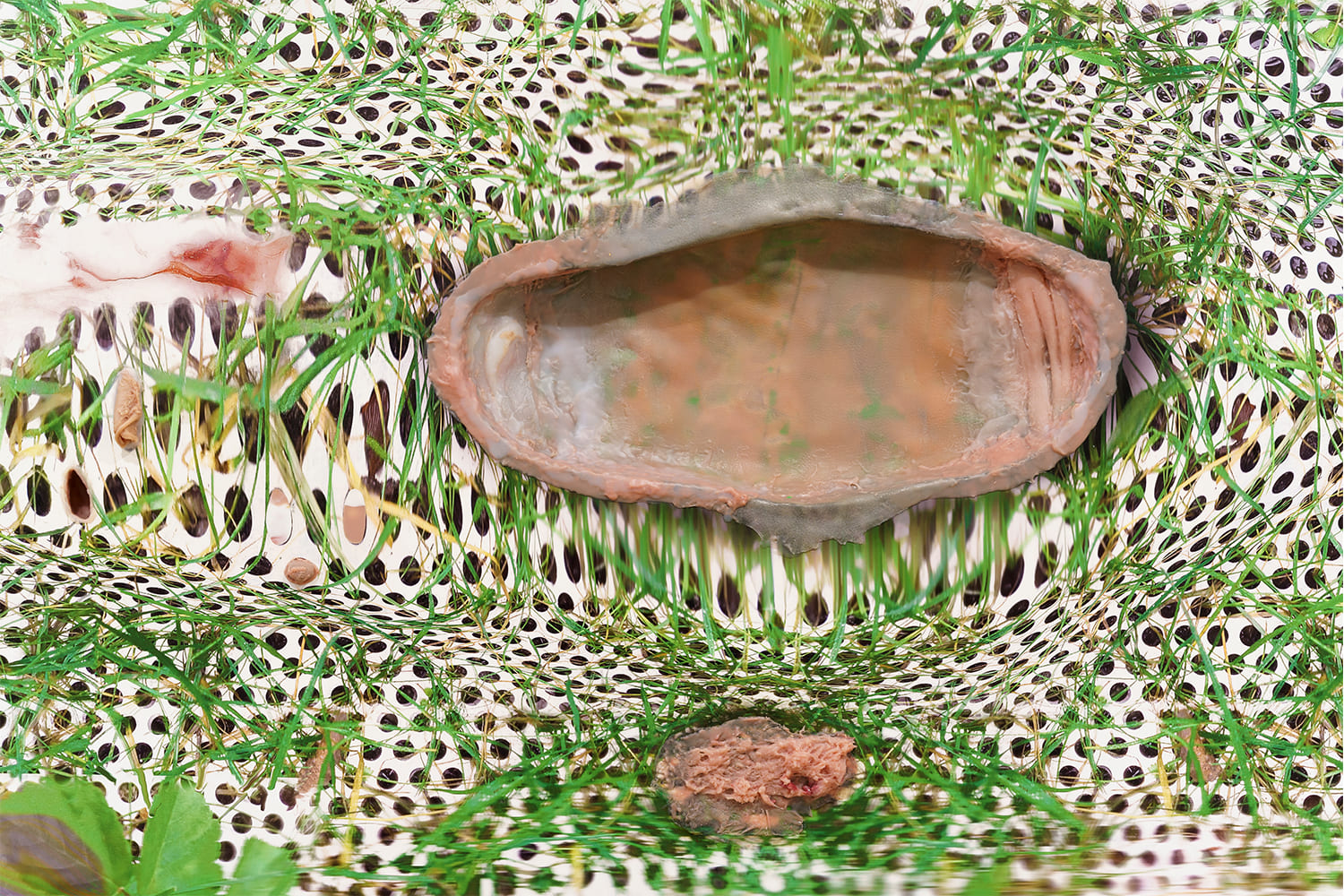

The interiors of the buildings Bucher chose for her skinnings thus carried either great personal significance for the artist, or had strong historical connotations — the line is, of course, fine. For example, several skinnings were created in the abandoned Bellevue Sanatorium clinic in Kreuzlingen, Thurgau, where Anna O., the first subject for Sigmund Freud’s studies of hysteria, was treated at the turn of the century.2 Bucher’s skins, which float awkwardly in the air or lie on the floor of the Swiss institution (Bodenhäute [Floor Skins, 1980–82]), parasitize in a deconstructive fashion the host body by chipping away at its edges.3 Said Bucher in 1981, “Peel off one skin after the other, discard it: the repressed, the neglected, the wasted, the lost, the sunken, the flattened, the desolate, the inverted, the diluted, the forgotten, the persecuted, the wounded.”

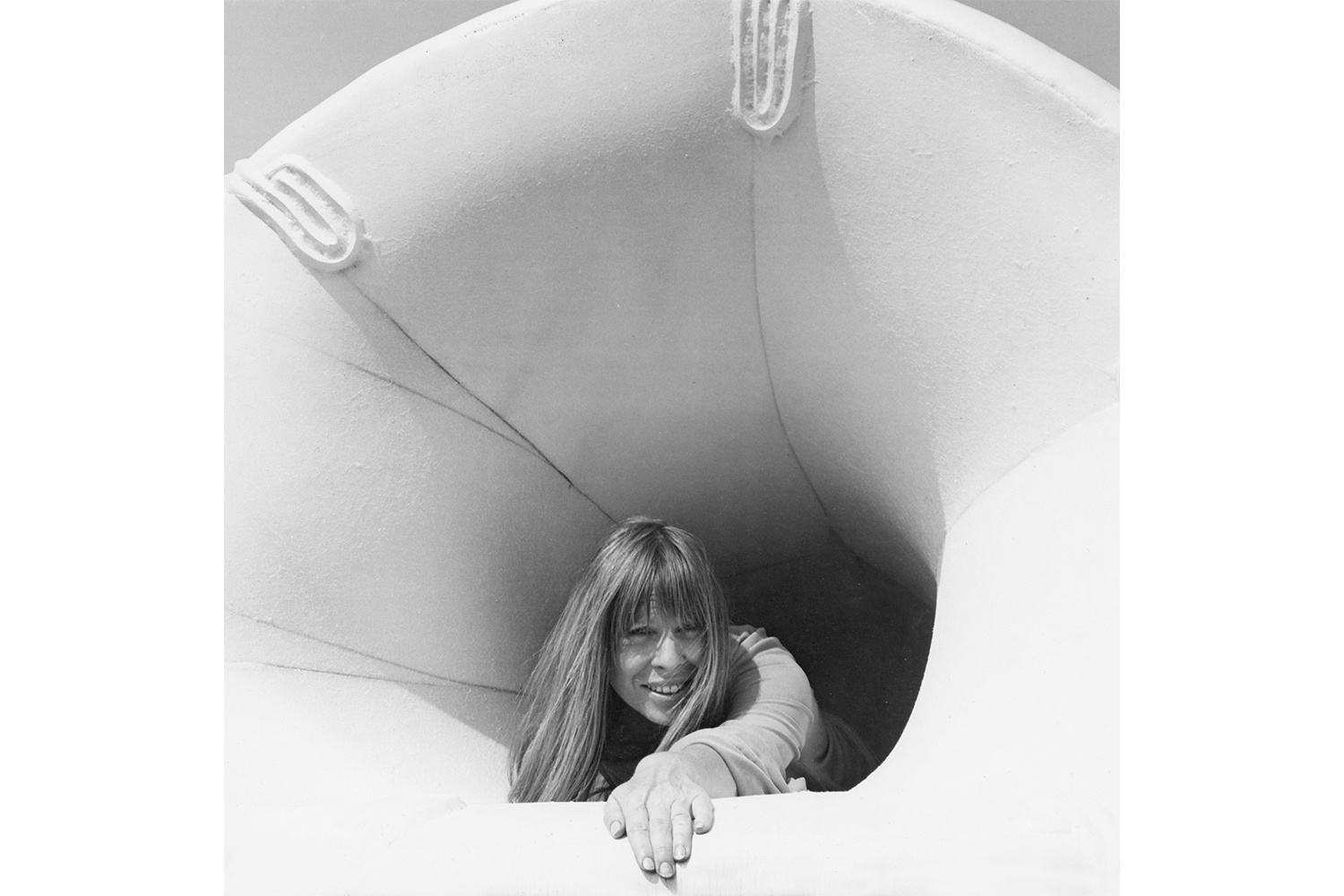

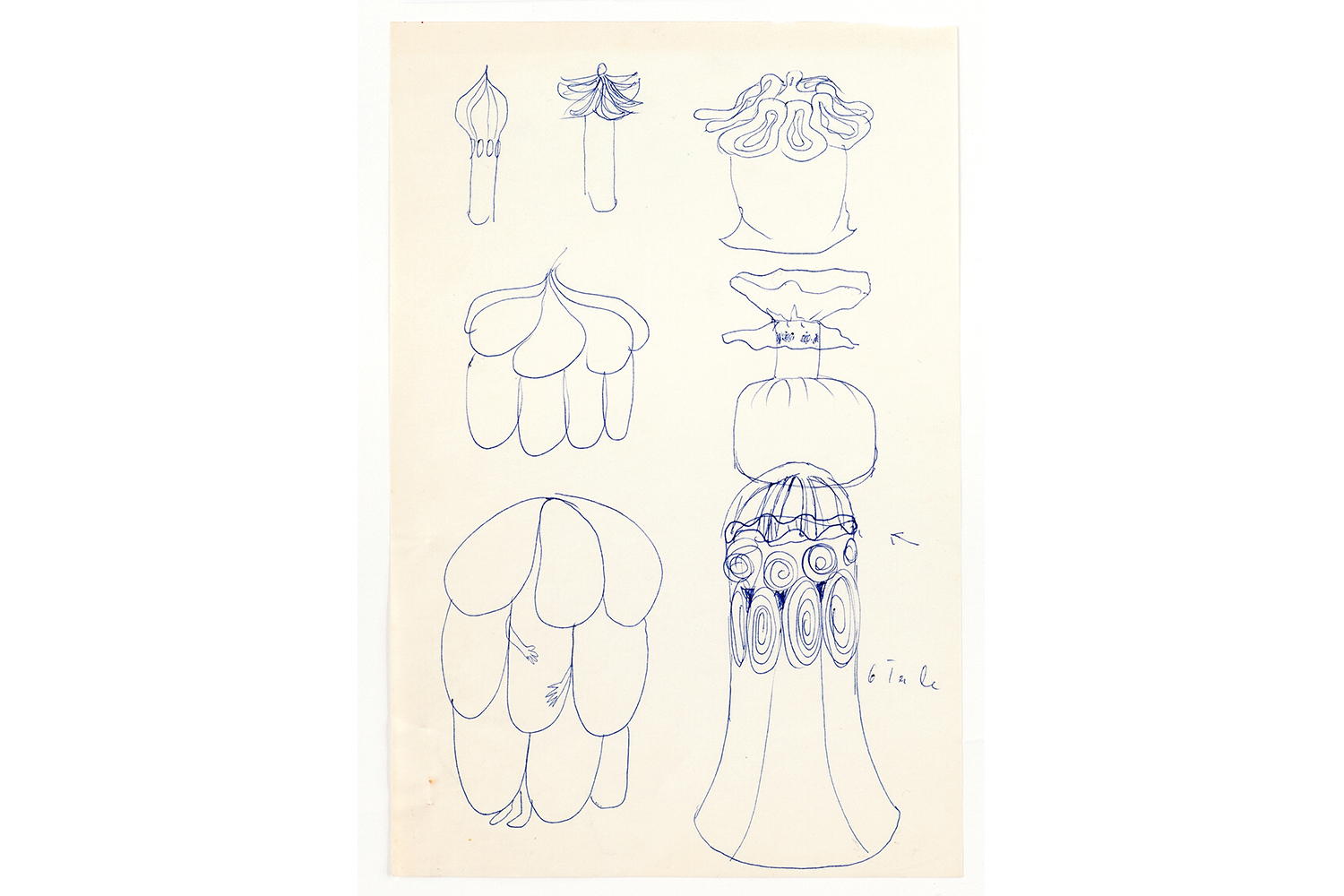

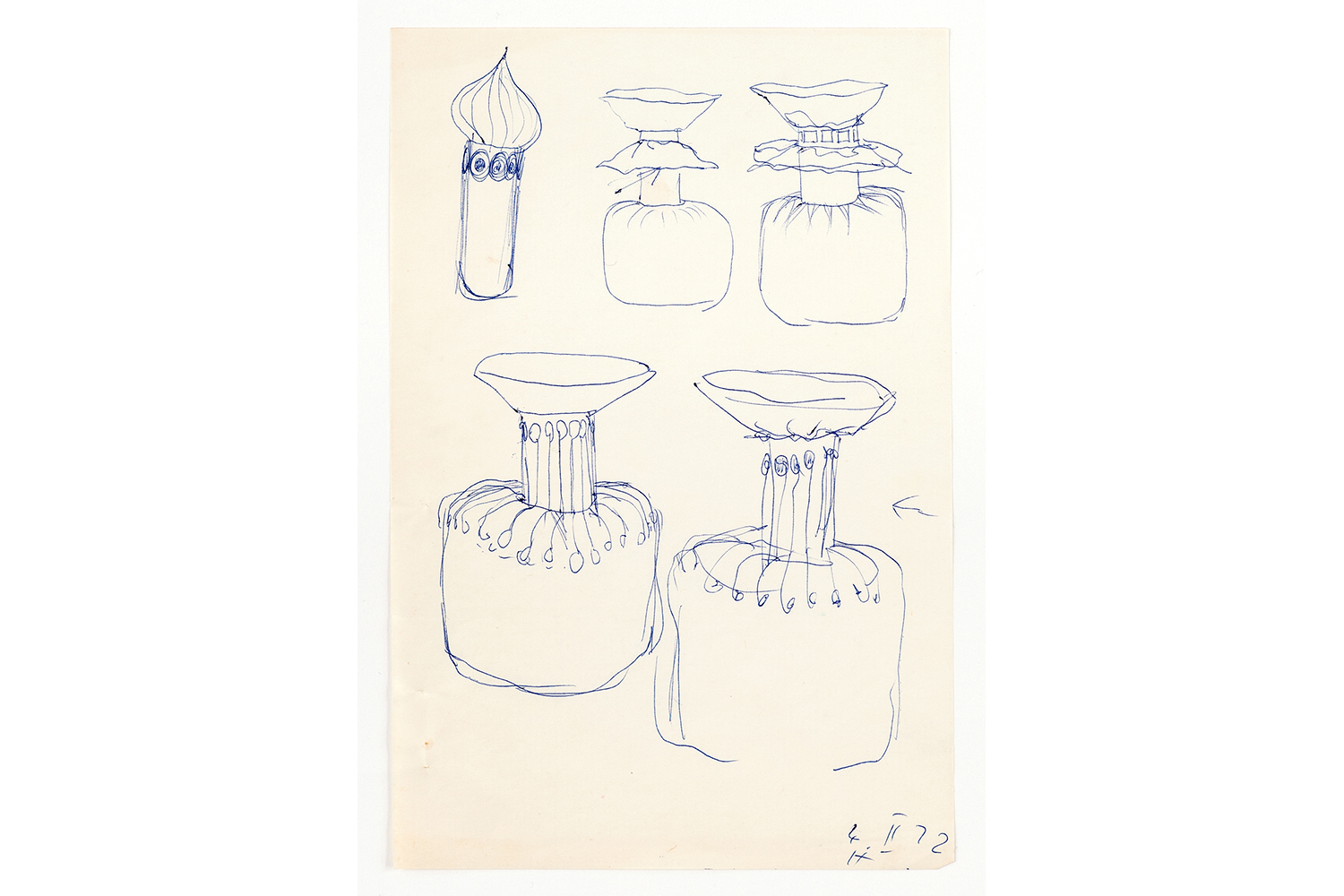

In addition to the skinnings, the exhibition brings together for the first time all the other major works of this neo-avant-garde artist, from early design studies from her student days in Zurich to the “Bodyshell” group of sculptures created during a period of experimentation in New York and Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, when Bucher came into contact with Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro at the California Institute of the Arts, became familiar with the work of Eva Hesse, and immersed herself in the then-burgeoning feminist art sensibility. “Bodyshells” (1972/2021) are wearable — and rather genderless — body sculptures made of foam with a shimmering mother-of-pearl coating. They bring to mind the Bauhaus fusion of dance, costume, and sculpture. Chronologically, the last group of works exhibited are the skinned doors created by Bucher on the volcanic Canary Island of Lanzarote, which served as the artist’s temporary retreat until shortly before her death in 1993. Devoid of their use value, the ghostly presence of these portals haunts the room.

“Metamorphoses I” makes clear that in her feminist art practice, Bucher did not simply transform the apparent objectivity of the status quo into something personal, intimate, subjective. Doing so might simply be a reversal of roles. Instead, she showed that objective reality is itself fraught, conflicted, and not neutral. Just like the unconscious, historical traces are indestructible, but they sometimes need someone to materialize them.