How do we swim in the same direction?

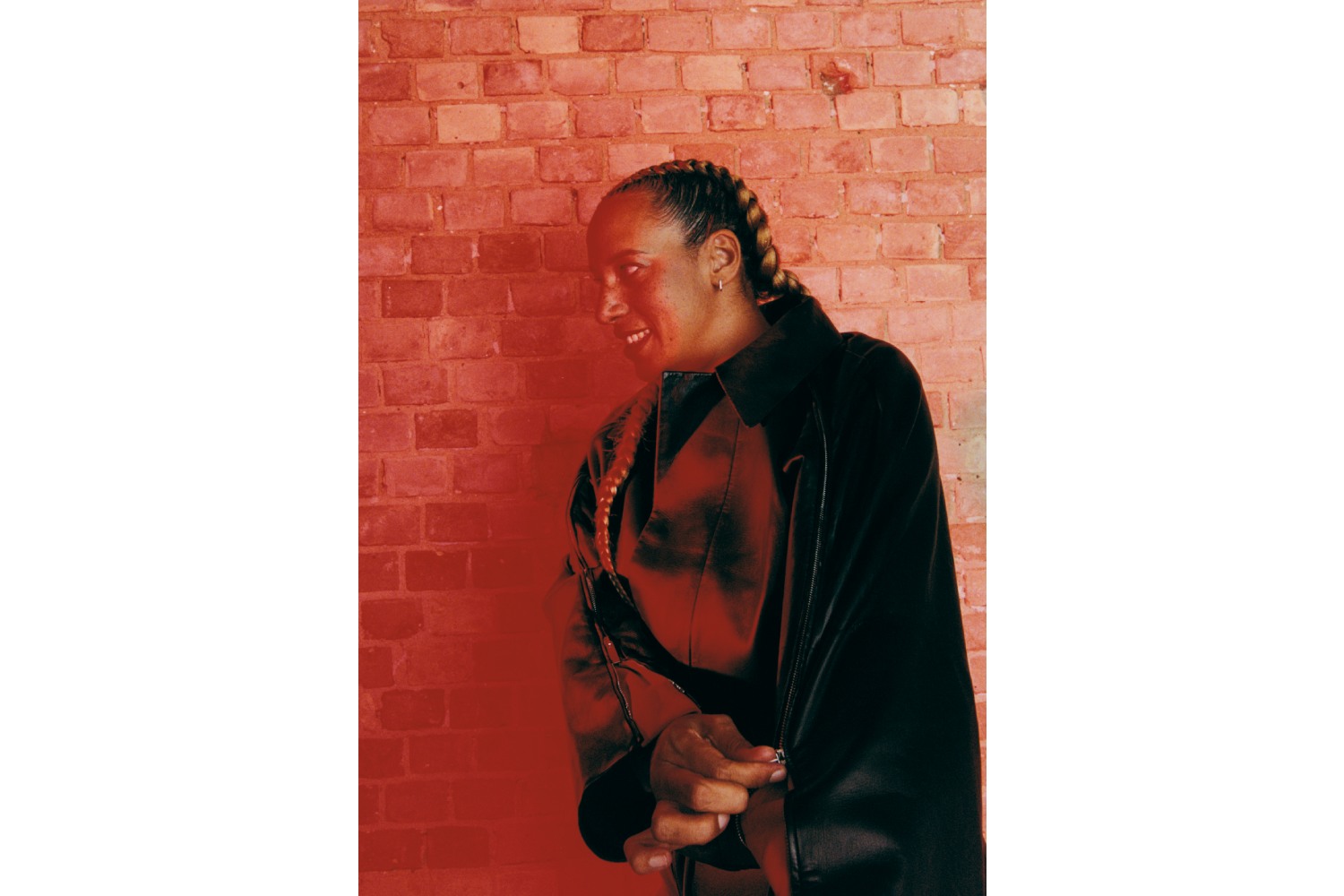

Free will is conceivable when humans are liberated from determination and can question the philosophical background of the rhetoric of freedom, which is exploited so dutifully by economic libertarians who have decimated social life for decades. It smells how it looks. Questioning political methodologies without necessarily rejecting one habitually venerated, Hannah Black plays cultural agitator by going beyond the cataclysmic rowdiness of looting and smashing windows. Her conceptual move is to differentiate between two methodologies: one. Biting and snarling in pursuit of ontological freedom. And two. A soft, pragmatic approach that aligns itself with persuasion. Which, mind you, is just another way of seeking ontological freedom. This isn’t to say Black hasn’t deployed the former, probably broken a storefront window or two, grabbed a crocodile Lacoste pullover, and thrown Pepsi bottles in riots in New York, Manchester, or port-side Marseilles, where she’s now based. It’s simply a new assignation of image as an alluring, potent, variable social force. Her video works, open letters, books, and performances have a unique talent for appealing to their audience through the contagion of political possibility quietly revealing itself to you. Stimulating the collective imagination, Hannah Black calls us to action through convincing videos and words that tell us all that there are ways to shape public opinions and attitudes outside of ruthless didacticism. Left organizers are not arbiters of ethical methodologies.

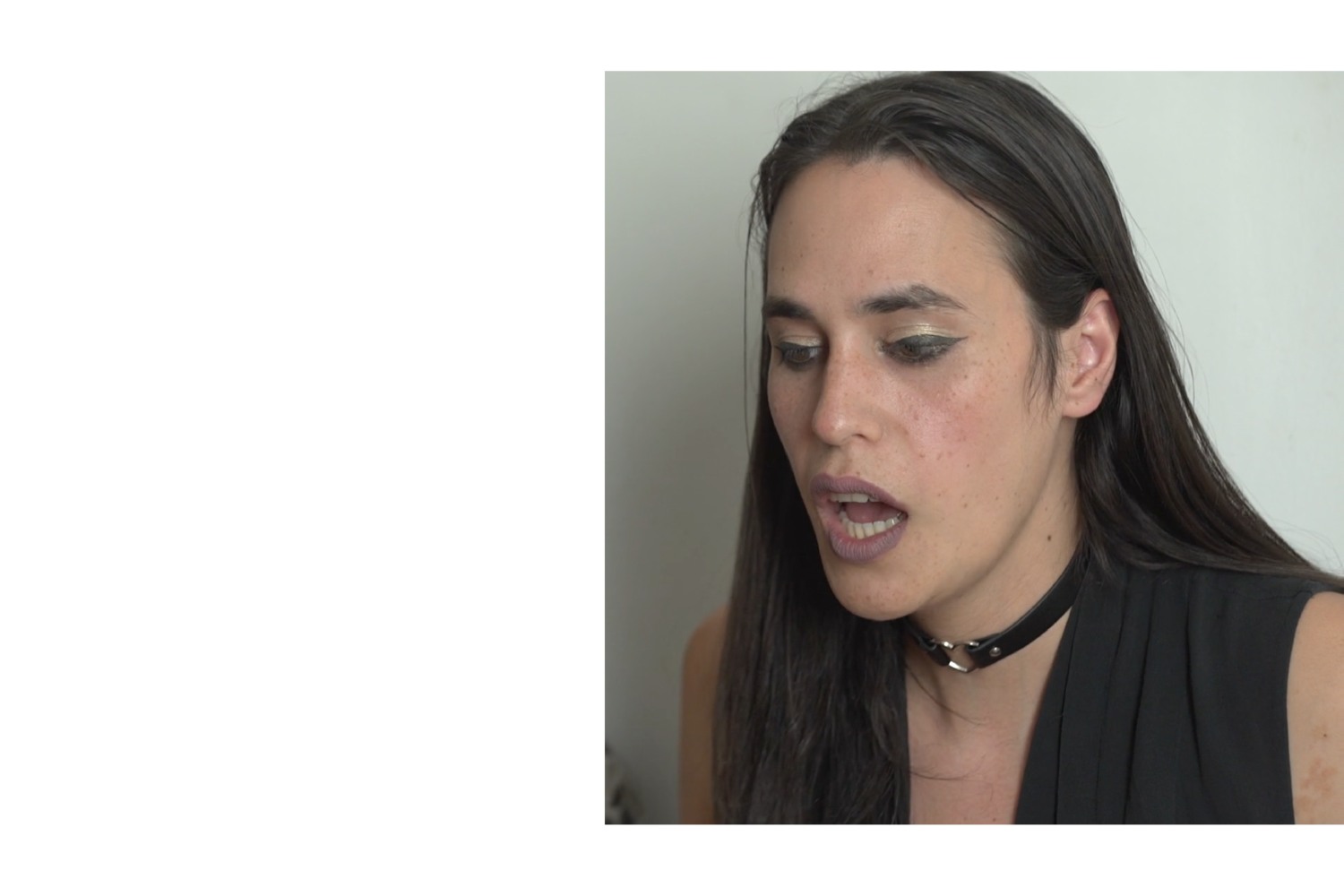

Estelle Hoy: Hannah, thank you so much for making time to speak with me; it’s deeply appreciated. Quiet rage and persuasive methodologies seem to creep into your new film work, Politics (2022) and Broken Windows (2022), recently exhibited at Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris, as part of “Condition,” a film series curated by Hugo Bausch Belbachir. In the growing complexity of the puritanical culture of the far left, you begin to detach yourself from the invigorating emotional scars of front-line protest interventions in order to replay messages second-hand in film. Unwilling to deny the overwhelming force of Black murder by white police, you capture clear-minded discourse from two New York-based abolitionists, Aaina Lakha and Kay Gabriel, who calmly articulate their revulsion of skewed racial cartographies in protest/looting practices. The employment of police force to contain the havoc caused by dispossession is utterly needless, Aaina Lakha asserts. At no point in the committed, open dialogue of the film do the participants yell, scream, condemn, or talk over one another. The quietly affected voices of tense witnesses speak candidly and smartly about fraught factions, with no confronting images of emotional “demonstrations” (the term applied if you’re white) or “riots” (if you’re Black). The initial organizer, Aaina Lakha, wears a black choker with a heart at the front of the throat in Politics, which seems perfectly emblematic of the argument. Choking systemic injustice in different ways, cutting off its air supply, and asphyxiating every fucked-up racial obstacle, you don’t interview the players so much as document their response sans interference. This is important. Having the fortitude to trust that our “duty” as artists is not to single-handedly ratify problems or even upend them; it is to inaugurate a steadfast allegiance to eschewing didacticism. Hannah, how can we press against violations in different ways?

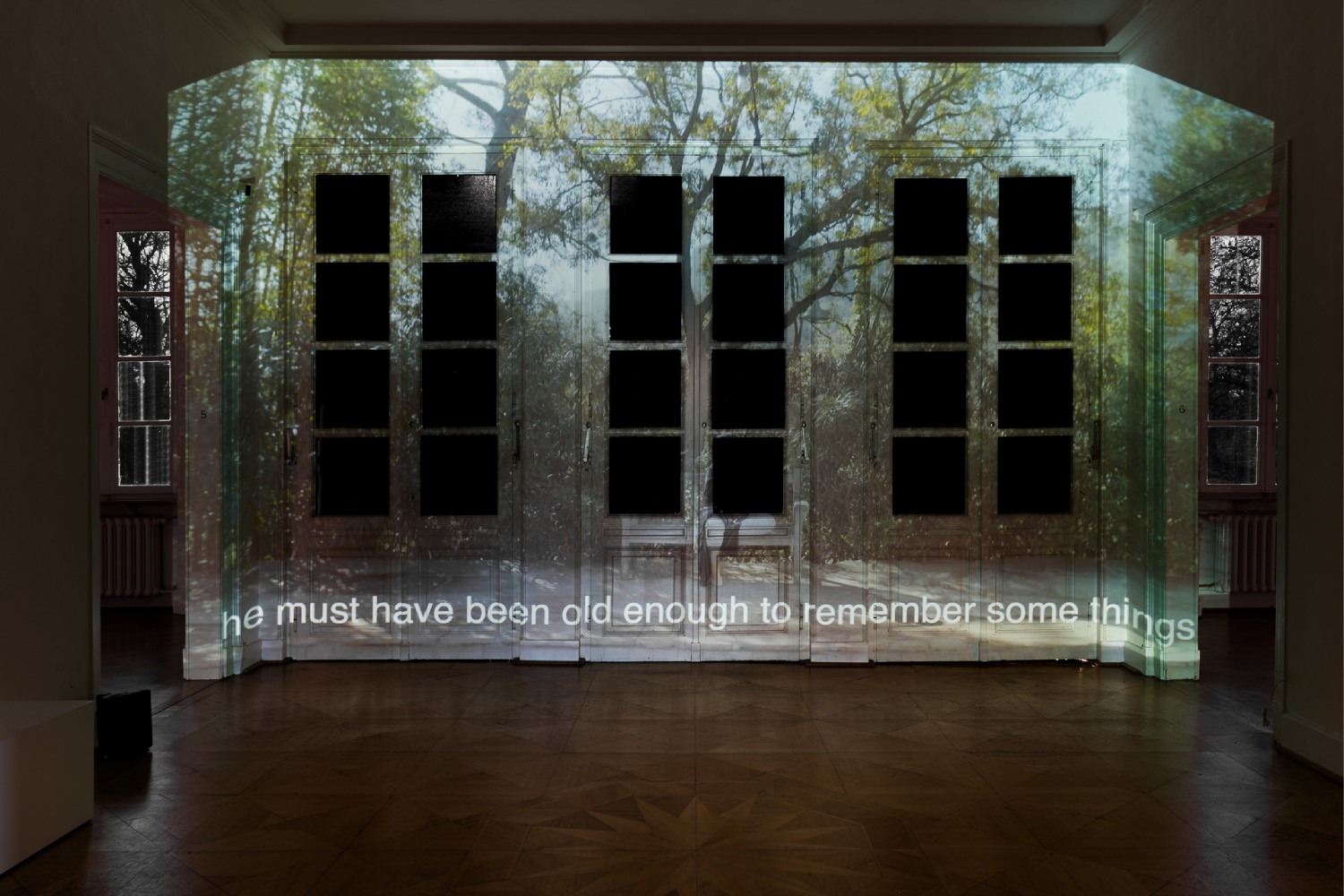

Hannah Black: These videos were made in 2021 for a show in Toronto in early 2022, curated by Jenifer Papararo. So they came from that time, closer to the 2020 uprising. At the time of the interview in Politics, both Aaina and Kay were organizers within the Democratic Socialists of America, a political organization whose membership increased a lot around the time of the 2020 uprising. This was perhaps because of an expectation that DSA would be able to harness the energy of the riots and transform it into political change. But it’s very hard to turn a riot into politics. That’s what we see them talking about. They have different stances, and some of my questions were confusing or provocative, so, despite the lack of yelling, the conversation actually contains a lot of potential conflict, which is one reason why they’re both smoking furiously throughout. Politics is exhibited alongside another video work, Broken Windows, in which I interviewed three witnesses/participants in some incidents of looting in SoHo during the uprising. All five of the interviewees in both videos are beautiful women (even the ones whose faces you can’t see). That was a deliberate casting decision. I was thinking of how a riot is figured as a kind of frivolous or excessive or histrionic or purely acquisitive act, as if it were a high femme activity. The two videos together present two extremes: the legible politics of public policy and elected representatives, which is the realm that the organizers are operating in, and the illegible politics of looting, which has multiple messy significances, and its value is contested even within left contexts. It is also illegal, so I can’t name or even show the faces of the interviewees, and I had to edit the video according to legal advice. That actually made it a better video. It’s an accidental collaboration with the law. The interviewees in Broken Windows describe literal broken windows, but “broken windows” is also the name of a notoriously racist zero-tolerance form of policing popularized by Rudy Giuliani, who was mayor of New York City from 1994 to 2001. Policing strategies like this make it clear that property rules everything around us. It’s commonplace to say that police murders of poor Black people are not really violations but just the most spectacular moments of a system working exactly as intended. So, I understand the last part of your question as: How do we come to experience the everyday workings of capitalism as a repression of other possibilities? I don’t have a universal description or prescription, but I’m interested in how that happens for people, even if just for a moment.

EH: Your interest in how it happens for others seems thoughtful and inclusive. Politics almost lulled me into a fuller understanding of racial violations despite, quite frankly, not having full access to their intellectual prowess. It was a dialogue in which I was out of my depth on occasion, but it only persuaded me to educate myself further. Google Dictionary got straight-up burn-out. Is the work within reach for a wide range of gallery-goers outside of a certain level of grad-school education?

HB: I think the difference in language across the two videos partly reflects the central difference they’re illustrating: the looting video is anecdotal and concrete; the politics video is abstract and theoretical. I enjoy the way they talk because it’s emphatic and libidinal.

EH: The work speaks the truth. Not the entire truth because there’s no way to say it all; it’s literally impossible. So language fails, and it’s through this exact impossibility that the truth holds onto the real, as Jacques Lacan would say, in abundant sweat and libidinal energy. I’m reminded of something quite emphatic that Lacan himself said: “The reason we go to poetry is not for wisdom but for the dismantling of wisdom.” Or thereabouts. Could you tell us a little about how this categorical exhibition was initiated?

HB: Hugo Bausch Belbachir at Fitzpatrick Gallery first proposed showing the videos there around the time of the riots protesting the murder of Nahel Merzouk, a seventeen-year-old murdered by police in Paris. Though it was made in the wake of the riots following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, I intend Broken Windows as a small celebration of all these moments of raw courage, the affirmation of the right to live. I love the Lacan quote. I identify with that description of what poetry does as dismantling wisdom, which is something like what a riot does, and of course, dismantling something is a way to clarify it.

EH: Energized dismantling is probably something you see regularly now with a new baby, isn’t it?! How has your experience of having a ten- month-old child clarified your understanding of art and politics?

HB: My baby is a wonderful little person, full of energy and love, like all babies. Through thinking so much recently about the perfection of babies, I sometimes get super sentimental and feel like I have a new depth of perception of how wasteful, violent, and perverse the world is — everyone started out as a baby and is, therefore, perfect. It’s crazy! Sometimes I feel this as an apolitical or para-political sorrow, and sometimes as a renewed desire for revolution. But now she’s starting to become a toddler, to individuate herself and say a pre-verbal version of “no,” and I have to say my own “nos” back to her. We’re gradually moving away from the boundless mommy- baby dyad and into a relationship that’s more about social values like negotiation, humor, conflict, and mutual generosity. Finally, I can start to accept that babies are born into culture, not nature. I spend a lot of my time at playgroups, mostly attended by working-class French parents. Here, too, I see the complications of the politics of social reproduction: I am viscerally grateful that the state provides these spaces for me and my baby, but there are glimpses of how the education system functions as a disciplinary tool, training people from a young age in colonial French ideology.

EH: Yes, a dis/advantageous collaboration with state law; we need a second interview! [laughs] In these films, the aspect of “apolitical sorrow” feels like it’s been reworked for revolution, a kind of roundabout way of getting to the same desired outcome. That is, finding various artistic methods that affirm the right to live. It’s a potent avowal and postlingual argument I can get behind with maximum esprit de corps. Do you think you bring the same social values you mentioned earlier — negotiation, humor, conflict, and mutual generosity — into your artistic practice?

HB: I think there is a lot of humor and conflict, definitely. I strive to be generous, creatively, intellectually, spiritually, and financially, but I don’t always succeed. Maybe there’s also an ongoing negotiation with myself and with the context of the art world. In relation to the first part of your question, I think everything that actually happens happens somewhere in between those two poles of apolitical sorrow and desire for revolution. Not only political events but also artworks and these “social values” we are talking about. I also want to this question and the previous one, I’ve been spending most of my time for the past few days following the Israeli atrocities in Gaza, and I’m thinking more than ever of the fervent almost contentless intensity of love of children, how it lives in a weird substrate or beyond of politics. I can’t stop thinking of the parents in Gaza, not only the bereaved ones; it breaks my heart, but also the ones trying to hold up the sky for their terrified children. Meanwhile, the Israelis are sharing images of kidnapped children, and some people are crying over those; they are as devastated and undone as I am by news of the brutalized and murdered children of Gaza. But in order to respond to this adequately, something has to happen that isn’t just affect; it isn’t just love or horror. And that’s the space of politics, a super-compromised, super- complicated space. (Also, free Palestine.) Thank you so much, Estelle.

EH: Free Palestine.

***

Black’s conditional commitment to politics and poetry is initiated privately and publicly, built upon dissonance, passion, metonyms, apathy, empathy, and all the ruins of the world. No one deserves anything, and everyone deserves something. How do we turn riots into politics, fill the raw political and cognitive fissures of injustice, find our sea legs, and endure in our unconditional pursuit of making us equal? How do we swim in the same direction? Black is looking to make and unmake the political refrain in all its messy signifiers, practicing new disciplines and systems as many times as permissible before getting caught, until we finally — and rightfully — register True North.