The title of Gray Wielebinski’s exhibition at the ICA is derived from the title of a 1978 essay by Samuel R. Delany, a distinguished science-fiction writer and critic. Attempting to map out a stylistic definition of science fiction, Delany explains that “genre conventions not only tell us what generally to expect in a given kind of work, but create a context which guides our interpretation of specific elements of that work.” Delany elucidates that with each new word we read, the intricate tableau we held just a fraction of a moment ago undergoes revision. Similarly, this exhibition prompts many questions that pull the viewer through the space, from one object to the next, through each artwork’s meticulously crafted materiality. Each enigmatic work demands a closer look and beckons the viewer to reassess what they

have just seen.

At the rear of the main exhibition space there is what appears to be a basketball scoreboard, Record of a Living Being (2023). The scoreboard declares in red LED lights that HOME are beating VISITOR twelve to eleven. But who are HOME and where is the VISITOR? As I am reading the score, time is passing. A timer is counting down, but to what? On the floor there are markings similar to those found on a basketball court, but not pertaining to the same dimensions. Where is the game? Is it over? What is happening now? What happens next? Has something just happened? The sound of cicadas buzz in the air and there is whitewash on the large windows of the main gallery space. All are part of the installation The Red Sun is High (2023). A doorway leading to darkness adds to the ominous atmosphere.

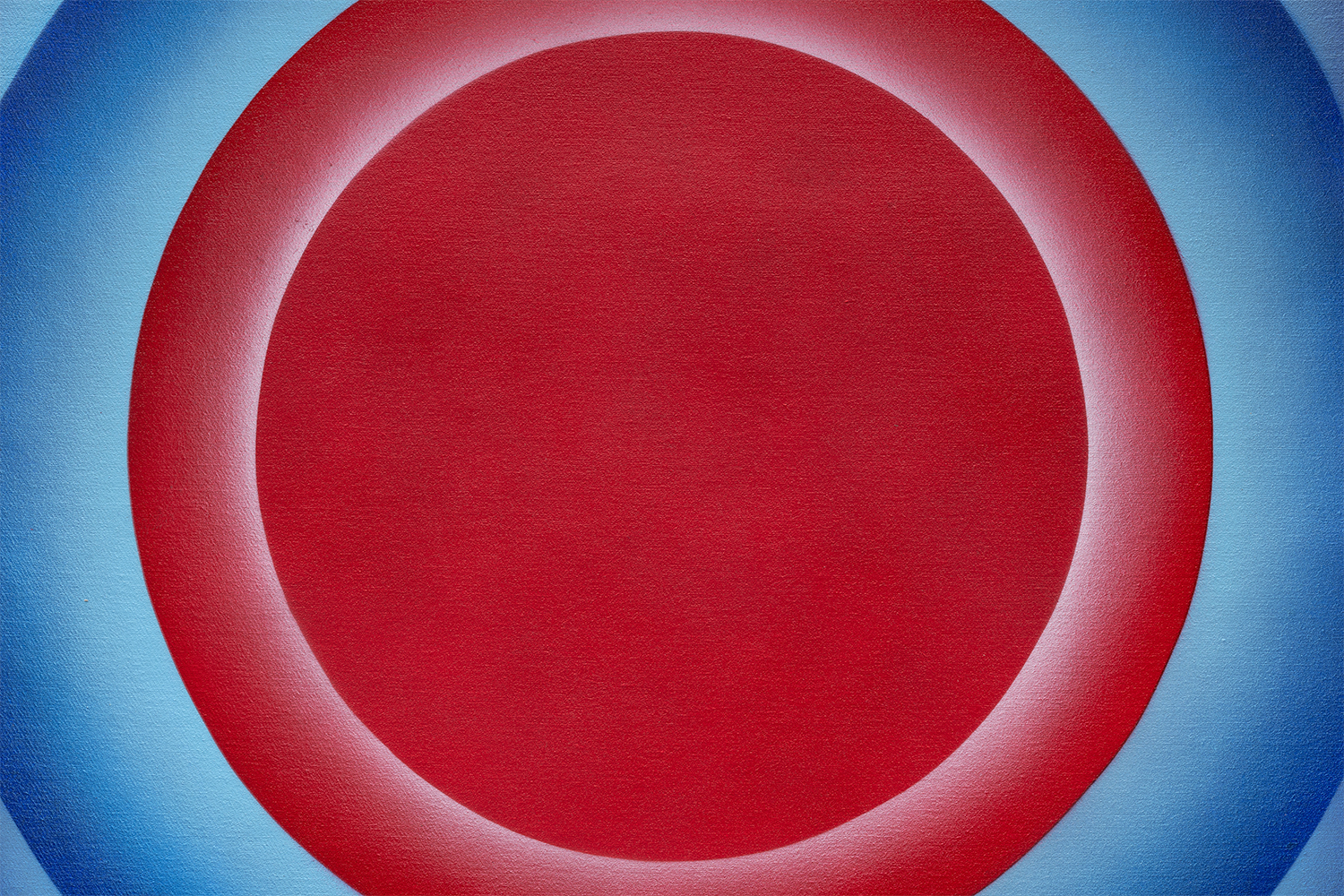

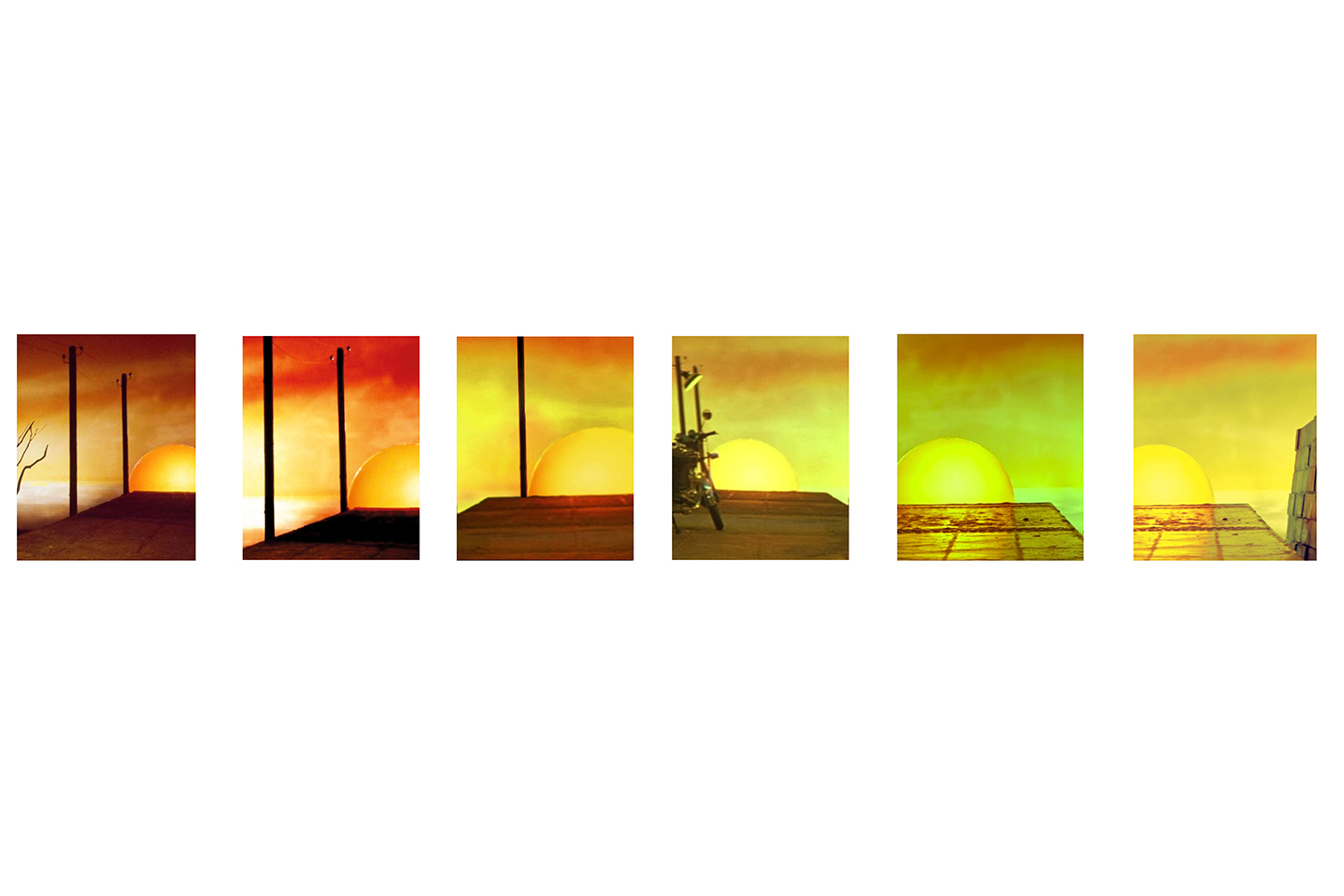

In the center of the space is a circular seating pit adorned with luxurious red velvet upholstery, The Sum Total of the Things They Aren’t Telling Us (2023), which offers a moment of contemplation but also emphasizes that something is lacking. There is a space for something communal but nobody is present. The space is sparse; all of the works point toward something having just happened — something perhaps even postapocalyptic. The works imply the presence of bodies that are not represented. From the pit I can see murals of various sunsets and hanging concentric circle paintings, the latter titled The End #1–5 (2023), which beckon with enigmatic allure. Like an arrangement of targets, each bullseye suggests a narrative crosshair — sunbursts casting shadows on untold tales — and a subtle nod to the chaos of a never-ending Looney Tunes end-credit sequence.

A steel sculpture bearing the name Two-Way Mirror (2023) serves as an entrance to a secondary room, an installation titled The Bunker (2023) at the back of the gallery. In stark contrast to the main space, which is illuminated, this area is enveloped in darkness and hushed tones. The walls are adorned with sound panels and dim blue lights crafted from steel lockboxes reminiscent of those that have proliferated as a result of sublet culture. The boxes, slightly cracked open, cast an eerie blue glow. Their initial function is now obsolete; there are no keys here. In the corner of this dark space is a screen inviting viewers to press a blue or red circle, in what appears to be a nod to the blue and red pills offered to Neo in The Matrix, but also the colors of both mainstream political parties of the United Kingdom. Pressing these buttons changes the score on the scoreboard hung outside the bunker, but it takes a few trips back and forth to determine this.

“The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low” pushes the viewer to search for details and connections without being didactic or conclusive — this despite being heavily mediated, with a catalogue, exhibition guide, and large wall text all present in the space. At times this unfurling minimalist dynamic comes close to undoing itself. Looking closely can reveal the edges of the work. A bronze crown of thorns titled Stigma (2023) rests on a white plinth outside the bunker. Looking very closely I can see that the crown is tied to the plinth with what looks like transparent fishing line. You can look but you can’t take this crown without causing a scene. The work is secure, protected, declaring itself within the value system it meanwhile points toward. Thus, Fredric Jameson’s overused quotation still stands strong: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.”