Elle Pérez is punk; they don’t have a shaved head or stomp around in bondage pants (although I’m sure they had their teenage moments). Elle Pérez is punk in their unwavering commitment to community, recognition of the importance of place, and resolute pursuit of the visceral. Their oeuvre depicts the bodily and the human but evades documentary — instead existing as a container for feeling, an object of emotion. We met for the first time at the American Academy in Rome where, after winning the Abigail Cohen Rome Prize, Pérez was in residence. On a tour of the studios this summer, I trailed behind a cohort of feline Italian patrons, feeling every bit the kid at the adult’s table. Most fellows had arranged their work into a legible presentation before the visit. Pérez’s studio was a patchwork of photographs (depicting Puerto Rican caves, New York’s queer club spaces, and ancient Roman architectural elements) cluttering the space. In the disorder, we were privy to process — a rag to a bull for any curator. Earlier this year, Pérez was appointed as assistant professor in photography at the Yale School of Art — we steal an hour between classes to speak about boxing, photographic value systems, and throwing a wrench in the gears of capitalism.

Ben Broome: I have a quote in my notebook by nineteenth-century essayist Walter Pater: “All art constantly aspires to the condition of music.” It’s an apt starting point to investigate your work because, when you first picked up a camera, it was within the orbit of a music scene. Do you feel Pater’s quote relates to your work?

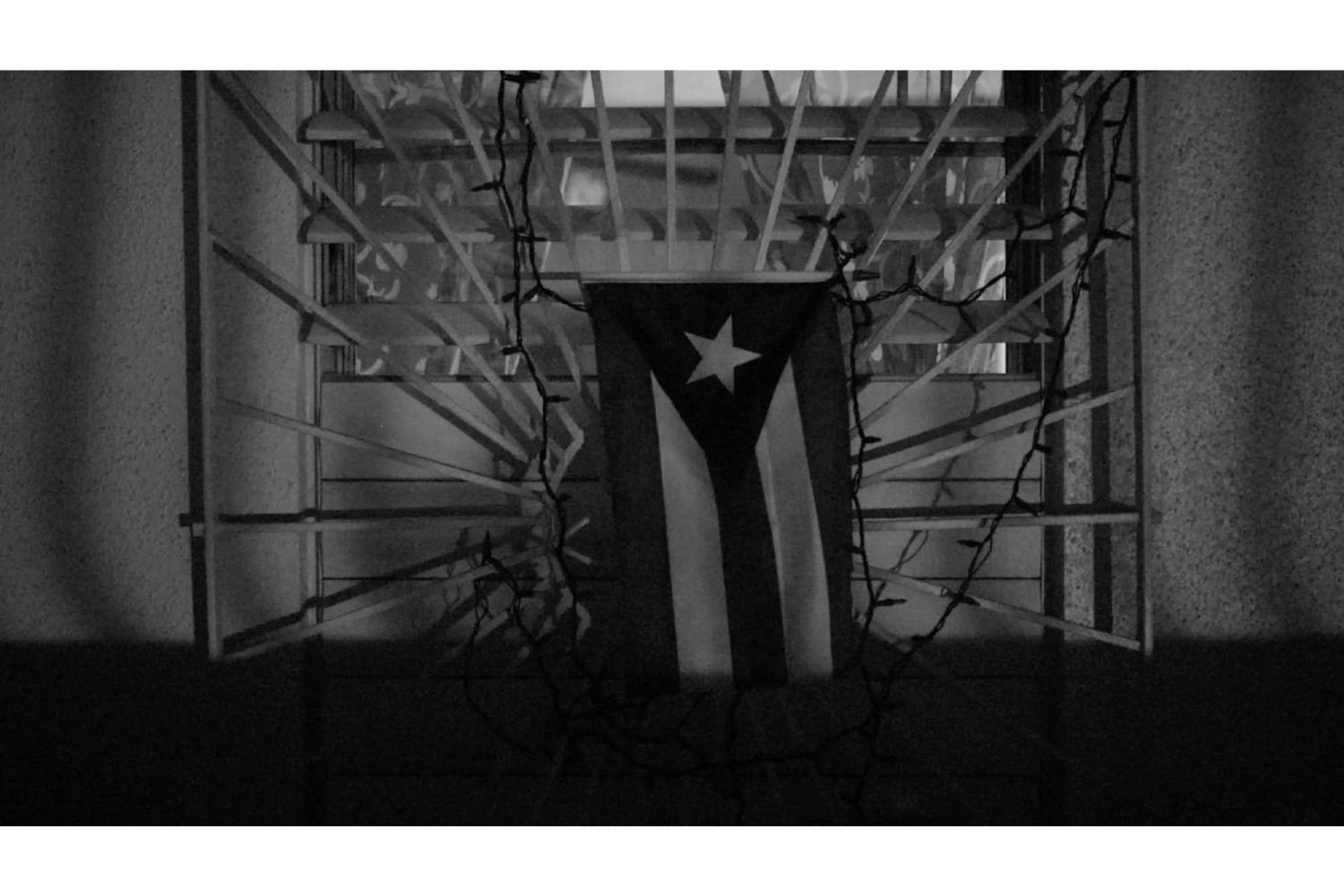

Elle Pérez: I love thinking about where that comes together and where it comes apart. I think where it comes together for me is the desire for something to be felt viscerally — to feel like you’re able to hit a certain note that has to do with a fact of living previously undescribed and, in my case, achieving a photographic description of the ephemeral condition of living. I consider art, music, and teaching as closely related because, fundamentally, they’re acts of communication. What is being communicated often isn’t discursive but is somatic. When I stopped relying on written or verbal descriptions, I started to feel like I had more tread; there was more grip to my making. I remember asking myself, “How does feeling and emotion show up in my practice?” That was really a question I lived with; it was only answered through years of work. My video work does have a lot to do with music and sound. Wednesday, Friday (2022) uses fifteen minutes of a generator’s drone paired with images from my great aunt’s porch. A static camera records light moving across a marina six months after Hurricane Maria when Puerto Rico was still in a continuous blackout. Occasionally, the neighbors would talk, or a car would pass — it was a different tuning of your senses — you’re paying attention to how the light moves, waiting for something, anything to happen. Fifteen minutes in, it flips to footage of this insane festival in Puerto Rico, the Festival de las Máscaras de Hatillo: street sounds, people yelling, and the DJ all blend. It feels overwhelming: you’re in the dark, in silence, watching a static image, and suddenly you’re thrown into chaos.

BB: Your entry point into photography was the punk scene in the Bronx, rooted in a DIY approach and an ethical responsibility to uphold community and space. How do those formative moments in this punk scene inform your output?

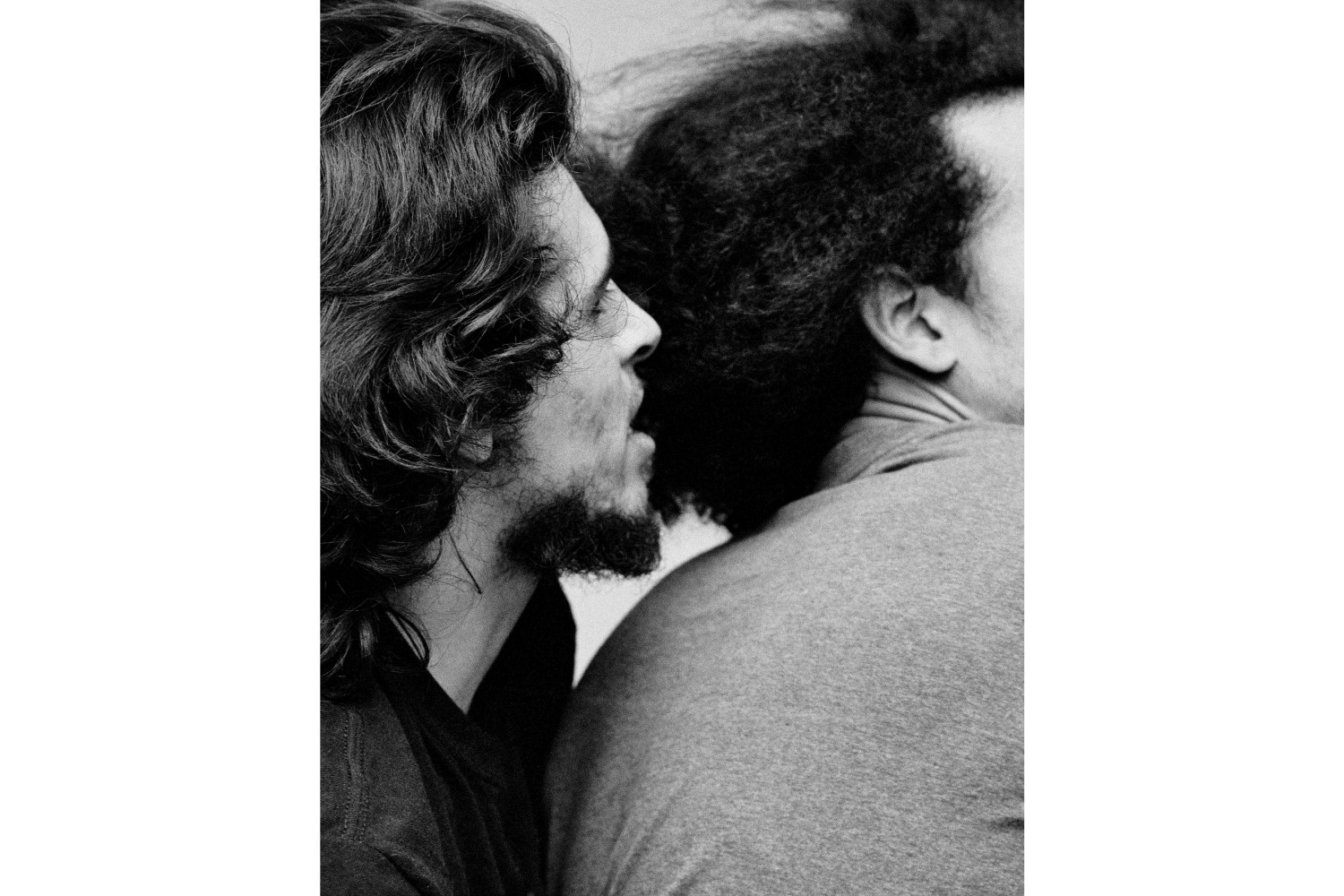

EP: One of the most impactful things that developed from that time was an understanding of subject as audience — the subject and audience were always the same group of people. This baked into my work a fundamental responsibility: I never think of the audience for my work as different from the people in it. Place and routine also became very important to me. That church basement was where I lived, where I loved, and where I would see my friends. The place where I was making art was no different from where I would live my life. This was an important fragment of understanding because now I make art where I live, with whom I’m living, with whom I’m loving. When I try to untangle my sense of artistic ethics as an adult, it all leads back to that basement as an early studio. It wasn’t hermetic: people came in and out. My knowledge of the landscape was critical because I knew when and where things would happen. The real gift was that my community let me take photos — that was the best training ground I could have asked for.

BB: Thinking about the foundations of punk and its anti-capitalist attitude, a powerful way to subvert capitalism is through a shared experience, energy, and euphoria — something that cannot be bought. These are qualities your work possesses. Do you consider your approach to making anti-capitalist?

EP: Definitely, that’s why I don’t do commercial work: I realized it was at odds with how I worked. What capitalism wants more than anything is to buy your joy, to buy your intimacy, to have your earnestness. And it’s not for sale. If you give me ten minutes with anybody, I can make you a good picture, but that becomes a lie at a certain point. I think I don’t want to lie.

BB: I see commercial photography as rooted in hyper overconsumption. It’s designed to be consumed en masse. Do you see art photography as an antidote for overconsumption?

EP: Art photography is an arena for ideas and for thinking photographically about how images structure our world and function within it. Photography within the context of art allows us to step back and postulate the making of an object that doesn’t function. When an object doesn’t function, what can it reveal about the world it came from? So many capitalistic gears are turned by photography — art photography is a wrench thrown in those gears. What that tells us about the world is so necessary, especially as we move faster and faster through stages of image production and image-based capitalism. Images will be legible to future generations in the same way I look at a Berenice Abbott photograph: I can understand how those skyscrapers went up and what she was looking at. I can understand her perspective as an artist and a human encountering a new world. The most fundamental difference between art and photography for hire is that my images get to live a different kind of life; they become more valuable the older they get. Commercial photography is most valuable before it is released, and then its value depreciates until it cycles back around into the inspiration sphere. I had an issue with the depreciating value of my work, and I realized very early on that the work I was making was for history. I don’t know what possessed me to think that, but, at age fifteen, that became my purpose.

BB: The art object has the capacity to appreciate with time, but, as a photographer, you have to contend with the dissemination of your images online — something that is much harder to manage or limit. Do you ever feel a loss of control over how your work is distributed outside of the gallery or institutional setting?

EP: When they go out into the world, images are going to do what they’re going to do. I think the struggle is really over the narrative — that’s where I fight my battles. Emerging artists should always be the water that pushes on the shore, and so, if my work was perfectly understood immediately, it wouldn’t be successful. For instance, with my work about body transformation and body exploration that was in the Whitney Biennial, people really wanted that to be a “transgender diary.” I was like, “You’re not doing that; that’s not what this is.” They saw the lineage and were like, “Nan Goldin, NEXT.” Even though that is part of who I am, they were ignoring the other stuff. That’s when I realized the necessity of introducing the collage work as artworks.

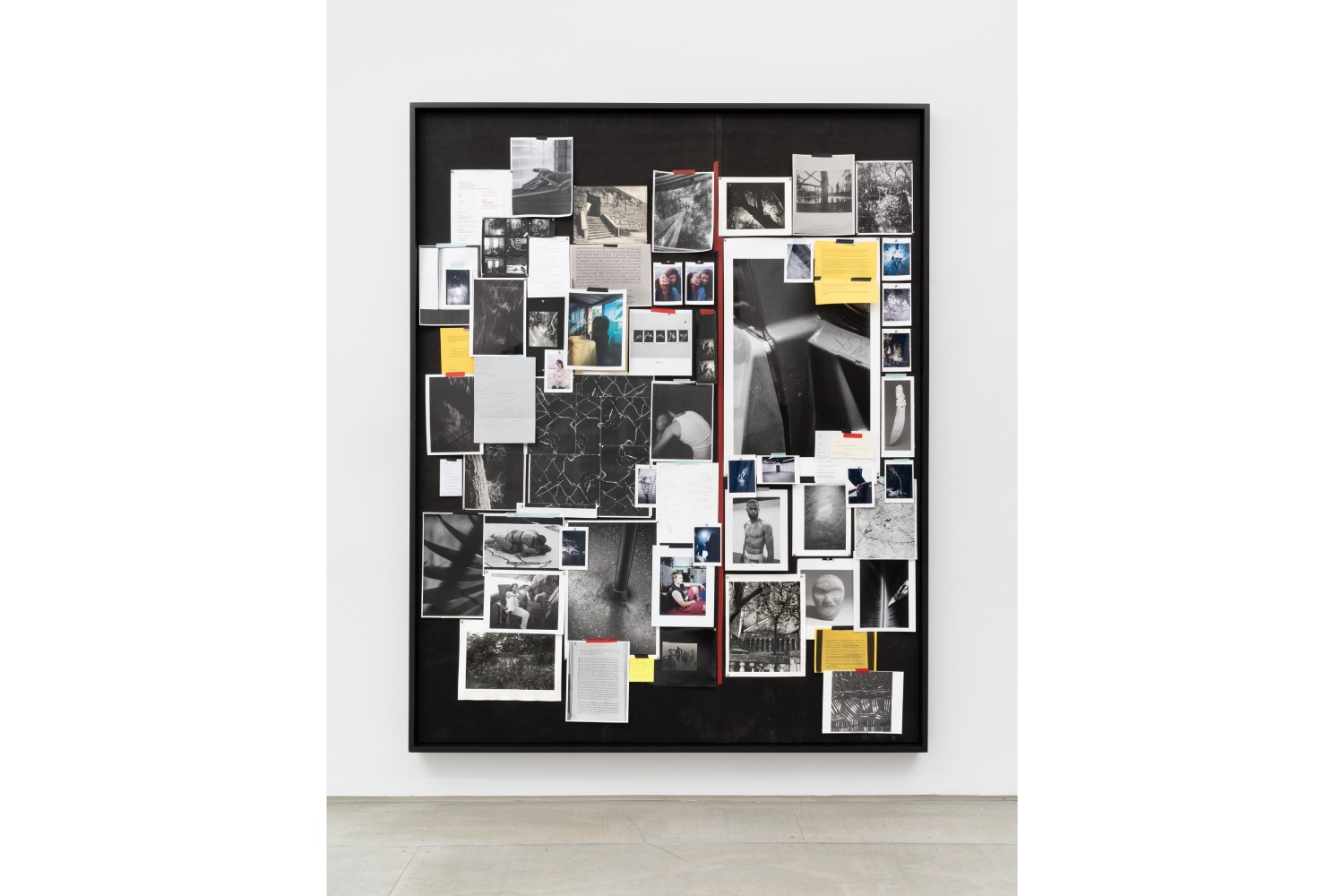

BB: Your collage works show that your references are many: you can’t look at that work and pin a specific narrative onto it. The process by which they’re made is very free and impromptu; you show up to the gallery with folders full of material and make the work on-site. Is this something you’ve always done? Texting with Elle post-interview, they offer an index for a section of guabancex; III, 2023: 1. A photocopy from Hervé Guibert’s Mausoleum of Lovers; 2. A photocopy from “The Happy Years” chapter of A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara; 3. The back of the Boxer at Rest sculpture at the Palazzo Massimo; 4. My photographic prints: the disco ball at Paragon, caves in Puerto Rico, Pappi Juice photos; 5. A page from Jose Oliver’s seminal Caciques and Cemi Idols; 6. Xeroxes, laser prints, and inkjets from my studio used to sequence and figure things out.

EP: I first showed collage at “Diablo,” my exhibition at MoMA PS1, but those works have always existed. They’re so intrinsic to my studio process that they became almost invisible as an artistic gesture. They’re impulsive. When I was in undergrad, I had a studio wall where all of these things were next to each other — my photographs, Martha Cooper’s photographs — a combination of aspiration, inspiration, juxtaposition, conjuring, and reading the impulses of the mind. It was a very important processing place because it was the ground, it was where things got worked out, and it was where things became. Later, I realized that I was taking what I couldn’t squarely put away and putting it on the wall. It was a way for me to attend to some of the unresolved questions in my own mind — partially through looking, partially through shooting, partially through this dialectic that would emerge between what was up on the wall and what was happening in the world. My goal for the last ten years has been to be more honest about what happens in the studio, bringing that into alignment with what happens in the gallery. Just showing nine discrete finely wrought images was not the whole story; it’s also important for the work to have a context backpack. What came between MoMA PS1 and my recent collage works was a series of binders. During COVID, I was moving between multiple places — I didn’t have access to my studio at the time, I’d been commuting to teach for years (five hours up and down the Eastern Seaboard between Harvard and New York) — I couldn’t keep a fucking thought together. I started to put photographs into these binders as a way to keep track of my thoughts. I realized through the binders that the boards and walls I was collaging deserved to be standalone artworks.

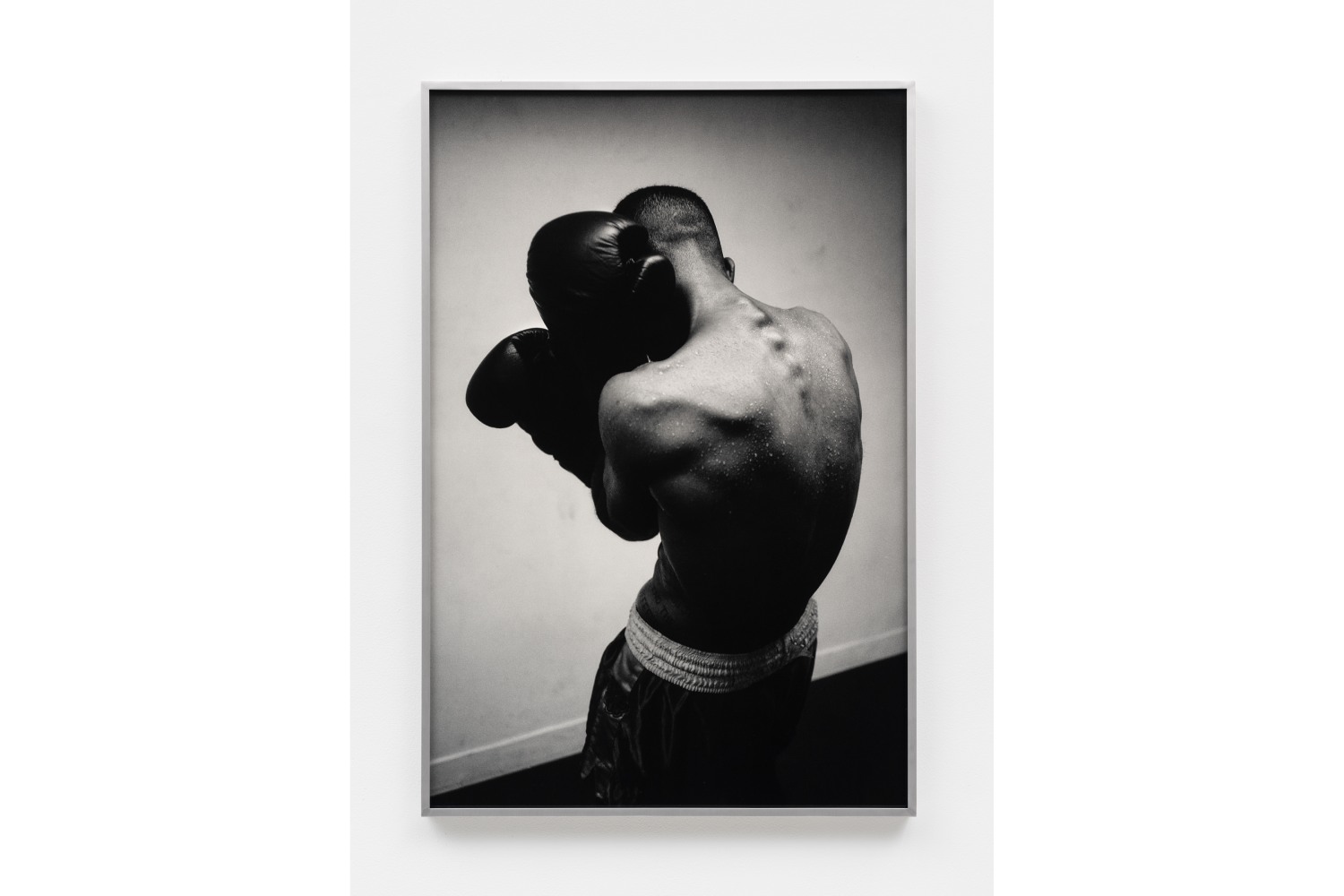

BB: That’s why I find your collage works so alluring — that insight into your thought process — the permission you give your audience to peek behind the curtain. In your recent exhibition “guabancex” at 47 Canal, the framework became an actual ground: the canvas of the boxing ring. When you’re in the gallery finalizing the work, are you thinking about the frame in which it sits as inherently linked to the subject matter (in this case, the boxing series)?

EP: All that thinking had already been done. All of those images had already been made. The magic happened when I caught the exact moment they were getting rid of the mat canvas at my boxing gym. I go to that gym every day; it’s a daily practice and it’s a daily community. I don’t even know most people’s last names, but I know their bodies. My gym really showed out for “guabancex.” I was worried my teammates were going to think I was weird, but they really “got it.” In retrospect, they’re the perfect audience for my work: when you box, you’re also working shit out on that mat, so of course, they get my own process of working shit out in an exhibition context. Their sweat is on that mat; in a way, it functions as a group portrait.