Croatian-born Dora Budor’s inaugural institutional exhibition in the UK, titled “Again,” takes place at Nottingham Contemporary, one of many organizations in the post-Brexit era facing cuts next year amid local council efforts to reduce spending. This is happening at the same time that private developments are springing up and encroaching on the skyline that surrounds the institution — itself, perhaps reluctantly, a purveyor of gentrification. It is within these scenarios that Budor’s exhibition cautiously and slowly unpacks the complex contexts and mechanics of the pastoral control that governs public behaviors.

While trying to pass through the café of Nottingham Contemporary to reach the entrance of the exhibition, I encountered a sign stating that, due to a recent tragic event, the café would be closing at 3:30 p.m. for the safety of staff and patrons. Later, a friend informed me that a twenty-four-year-old man was attacked and killed outside the building in December 2023. Several teenagers were arrested in the weeks following the attack, which has shaken the community and the whole country.

The sign on the door also stated that access to the café was still available through the main entrance. This led me to climb the stairs and discover an alternative way into the building, a large glass door set ajar, which did not seem to loudly announce itself as an entrance to the exhibition. Upon slowly entering the space through this door and picking up an information sheet, it was revealed to me that this “entrance” was in fact an artwork, Untitled (2024), an airlock door left ajar, one usually only intended for incoming and outgoing freight. I had entered the building the wrong way, and yet, here I was, inside the building, immediately disoriented not only by this readymade gesture but also considering its proximity to the tragic conditions that led to the shut door of the café.

A.U.D. (I – IV) (2023) takes the form of long, slanted, linear objects, raised just a few feet above the ground, cast from cardboard liquor packaging. These hang from the longest wall in the first room of the exhibition. The works are reproductions of Victorian-era urine deflectors from a passageway just off Fleet Street in London, used to stop men from urinating. If these objects functioned here, they would repel the urine while presumably also absorbing it. Formally removed from their original setting, the aesthetic of these objects resembles minimalist sculpture. A more specific and infamous ready-made fountain, debatably made by Marcel Duchamp, also comes to mind. Hanging opposite are two of Budor’s Dominoes (2023), made from the ground powder of placebo tablets placed on what looks like sandpaper or cloth, held tight and protected behind plexiglass covers.

The power cables of a Makita Job Site radio guide the viewer into the second room. The molds of the urine deflectors are also present in the second room but not listed as works. It is as if the installation of the exhibition was paused or intentionally abandoned as a gesture.

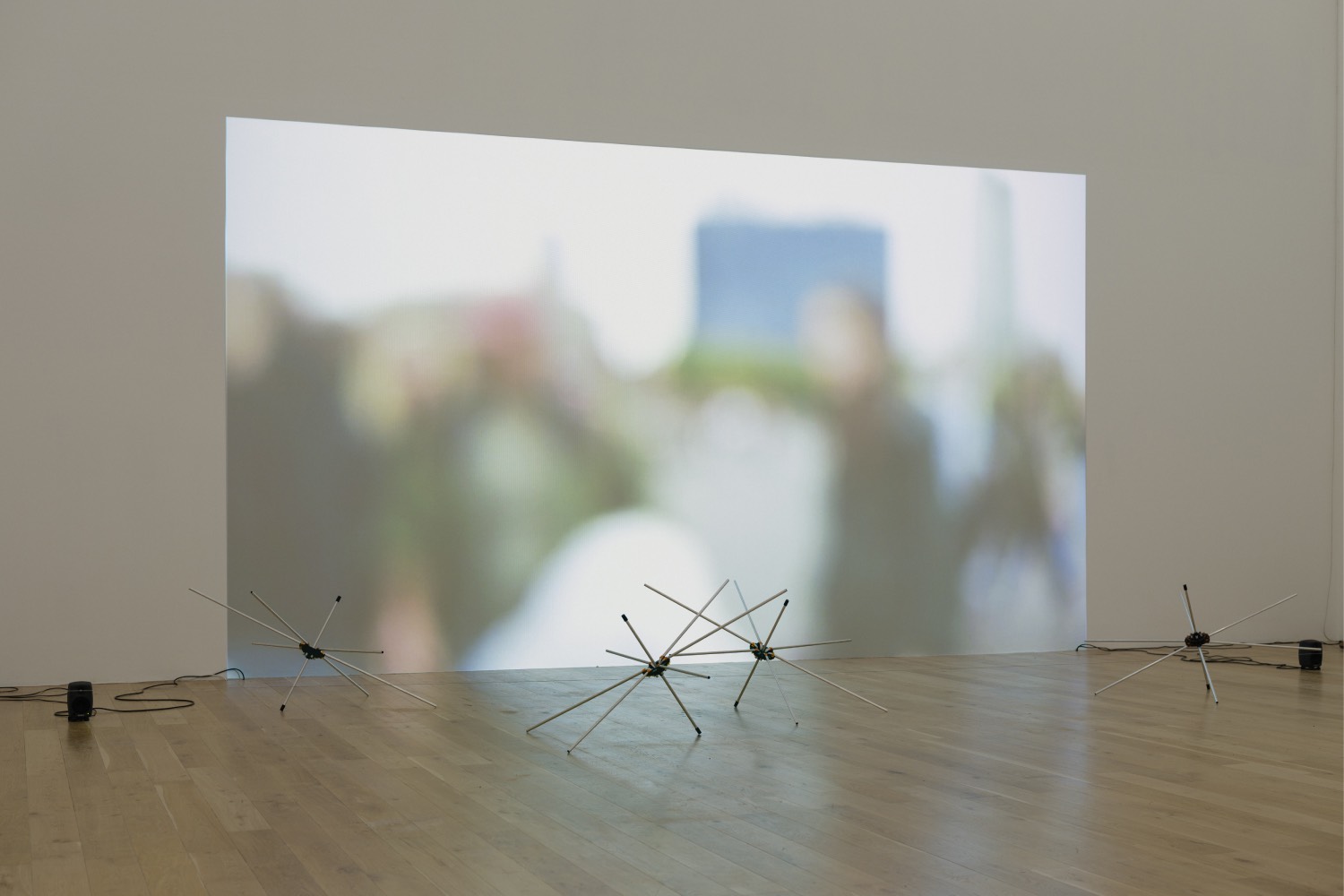

The moving-image component of Passive Recreation (2024) was shot on location at Little Island, situated on a pier on Manhattan’s West Side. The location, which was a previously well-known cruising location in the 1980s, has now been transformed into a site that invites the so-called “general public” to take in the view. The design features of the island dictate the camera’s chorography, wherein the image turns upside down or blurs at times. In front of the projected image are rotational grazing wheels, typically used to control and regulate how animals eat. A live wire that would otherwise be used to keep cattle in place here acts as a barrier between the projected image, the viewer, and the wheels. Out of sight of the invigilator, I lightly touch the wire, which seems to trigger a sound emitted from the speaker in the previous room, immediately bringing me to the attention of the invigilator.

A small ground-level work placed adjacent, Always Something to Remind Me (2023), contains forms that resemble Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s readymade Enduring Ornament (1913). The accompanying information sheet reveals that the objects are made from the smelted metal of a New York City rental bike — again calling into question everyday objects.

“Again” proposes the ready-made as an agent that still holds political potential, not only as a means of questioning value in relation to what constitutes a work of art, but more urgently as a perhaps reluctant methodology that might reveal the structures of control which determine the semiotics of our lived environments and politics.