Perhaps appropriately for an interview on a cold, dark, January evening, the first question I ask Gray Wielebinski is one about reflection. How has he metabolized the last year, which included a major solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, “The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low,” and his commission for the Selfridges Art Block, “Exhibition”? There were also two solo shows in Los Angeles, “Fratricide” and “Love and Theft,” and group shows in Madrid and Milan, with the latter being a show he co-curated: “Motherboy.” “I’ve completely flipped from looking outwards to turning inwards,” he explains. “Being introspective and able to reflect is offering me a different perspective; it’s good to give it some space.” Wielebinski’s expansive and diverse multidisciplinary practice, which incorporates installation, video, drawing, performance, collage, and sculpture, probes the intersections between gender, sexuality, and the social. His recent work has been particularly focused on power, surveillance, secrecy, and the mythology of nationhood. We spoke about process and psychoanalysis, among other things.

Philomena Epps: How do you approach making a new body of work?

Gray Wielebinski: I usually like to work on multiple things simultaneously. Making collages is a recurring drive for me, along with drawing, as a way of collating and mapping out ideas. I have a backlog of materials I can use. When I was working on “The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low” at the ICA, London, which was very site-specific and conceptual, I had such a strong urge to make stuff with my hands, which led to the production of the works shown in “Fratricide.” It was nice to have that sense of balance. Right now, I feel the need to be more hands-on. I have this compulsiveness with making that feels intuitive, and I’m starting to trust myself more. Something will click during that process. I’ll get obsessed and go down a rabbit hole. It feels like being a detective pinning strings on their evidence board, where suddenly I’m all guns blazing, “I’ve got it!” I’ve just been re-watching Mad Men, actually. You know that episode where they all get shot up with speed?

PE: I knew you were going to say that episode.

GW: It’s so good. I wrote this down and texted it to Asa [Seresin, Gray’s partner]. When Don says to Peggy, “I want you to go the archives. Look in 1958 or ’59 for soup. You’ll know it when you see it, and it’s going to crack this thing wide open,” while they’re all spending the weekend at the office trying to finish a campaign for Chevrolet. It’s such a ridiculous moment, but Don delivers the line with such conviction. I just felt like, “That’s me; that’s my creative process. It’s cracked right open, and I’m ready to go.” That feeling is so good, and I love it. I’m waiting for the next one to come. But the process can sometimes feel like I’ve had to dig in the archive for soup while I’m supposed to think about cars.

PE: Let’s talk more about collage. You’ve spoken previously about how your practice invokes the process of collaging through its mixture of references and interpretations, which I found intriguing; this concept that the juxtaposition of ideas can also be reflected through a juxtaposition of materials. I went to a talk Gavin Butt gave at UCL last night, where he suggested that the interdisciplinary practices of the 1970s similarly reflected the quasi-utopian desire during that period for politics and culture that transcended social hierarchies. I’m wondering about your relationship to collage as both form/medium and as principle/methodology.

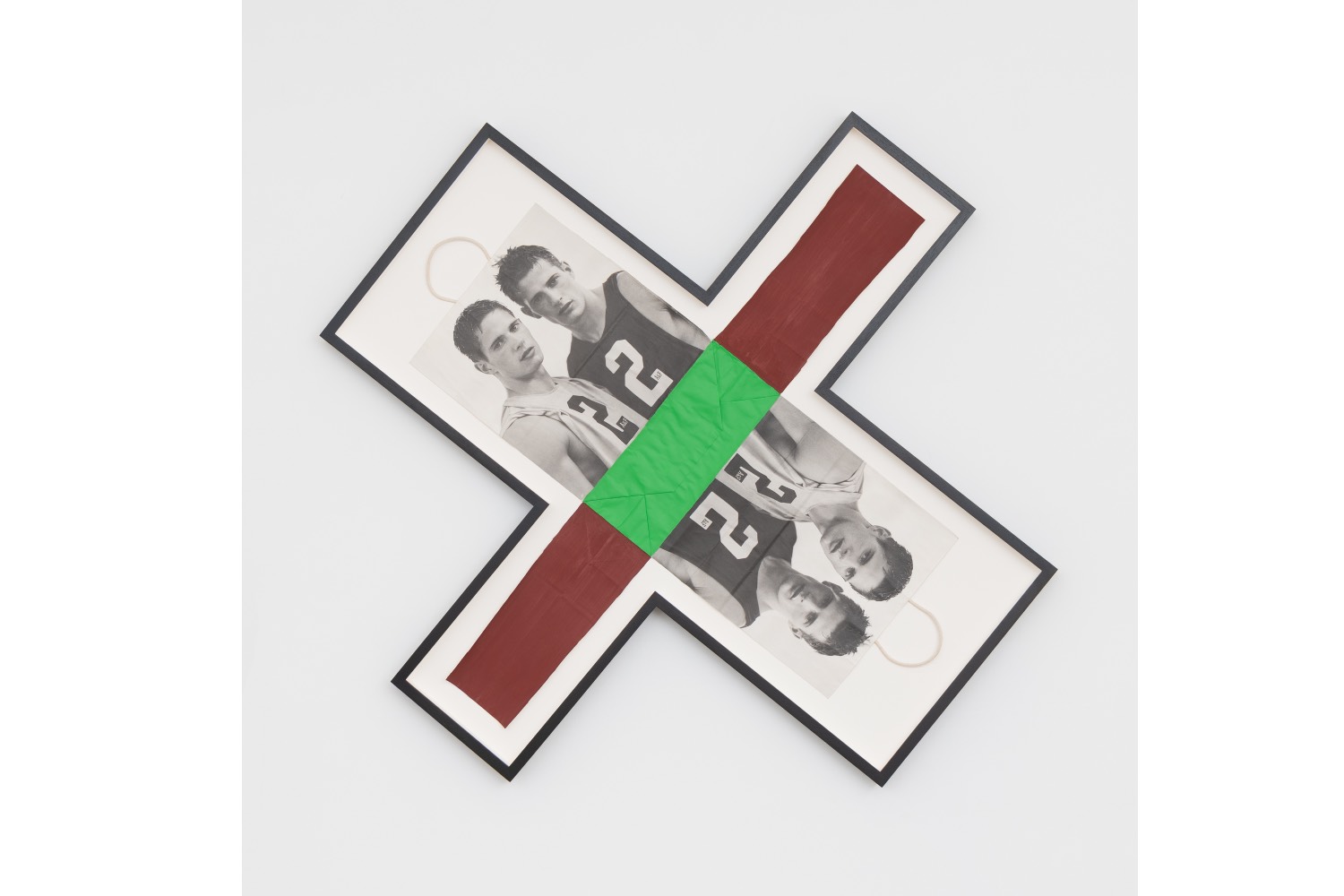

GW: I see the ICA exhibition as being a collage show. Although there was no literal cut-and-paste work, the methodologies were collaged. I was thinking about Samuel R. Delany and Rainer Werner Fassbinder as an entry point for thinking about queer aesthetics, queer art, and queer theory. There’s this notion of cutting up the world as a form of utopianism, which Heather Love talks about in Underdogs: Social Deviance and Queer Theory (University of Chicago Press, 2021). Everything we have exists already, so how can we reassess and rearrange it? That feels closest to my ideology. Collage is a medium with a total hold over me: it has its foot on my neck. There are endless possibilities and combinations. It’s also a time-based and performative medium; recording how I felt on that day, in that moment, and when I decided to put these things together. I might never make that connection on a different day. Sometimes I feel more vulnerable showing collage as you expose yourself. Not only do I use sexual imagery in the collages, but they also feel sexual, even humiliating. I have a desire and an impulse to create them that goes beyond the intellectual or even conscious. It has this control over me like I’m under a spell.

PE: The scale and portability of the practice are also interesting, the idea that you can set up your station wherever you are. For example, the work in “Fratricide” was made in your parents’ garage.

GW: That context felt very Freudian in a very literal sense. Asa was having top surgery from the same surgeons that I had my top surgery with two years before. I was caring for him, my mom was in the house, and I was down in the garage cutting up bodies. Making collages is almost childlike. It reminds me of the American suburban teen landscape and how the compartmentalizing of space functions when you’re a kid. You’re lucky if you have your own bedroom, or you might have a car or a school locker. These are all little worlds and pockets of space where you can signal your identity or show your taste.

PE: I took the task of decorating my school homework diary very seriously.

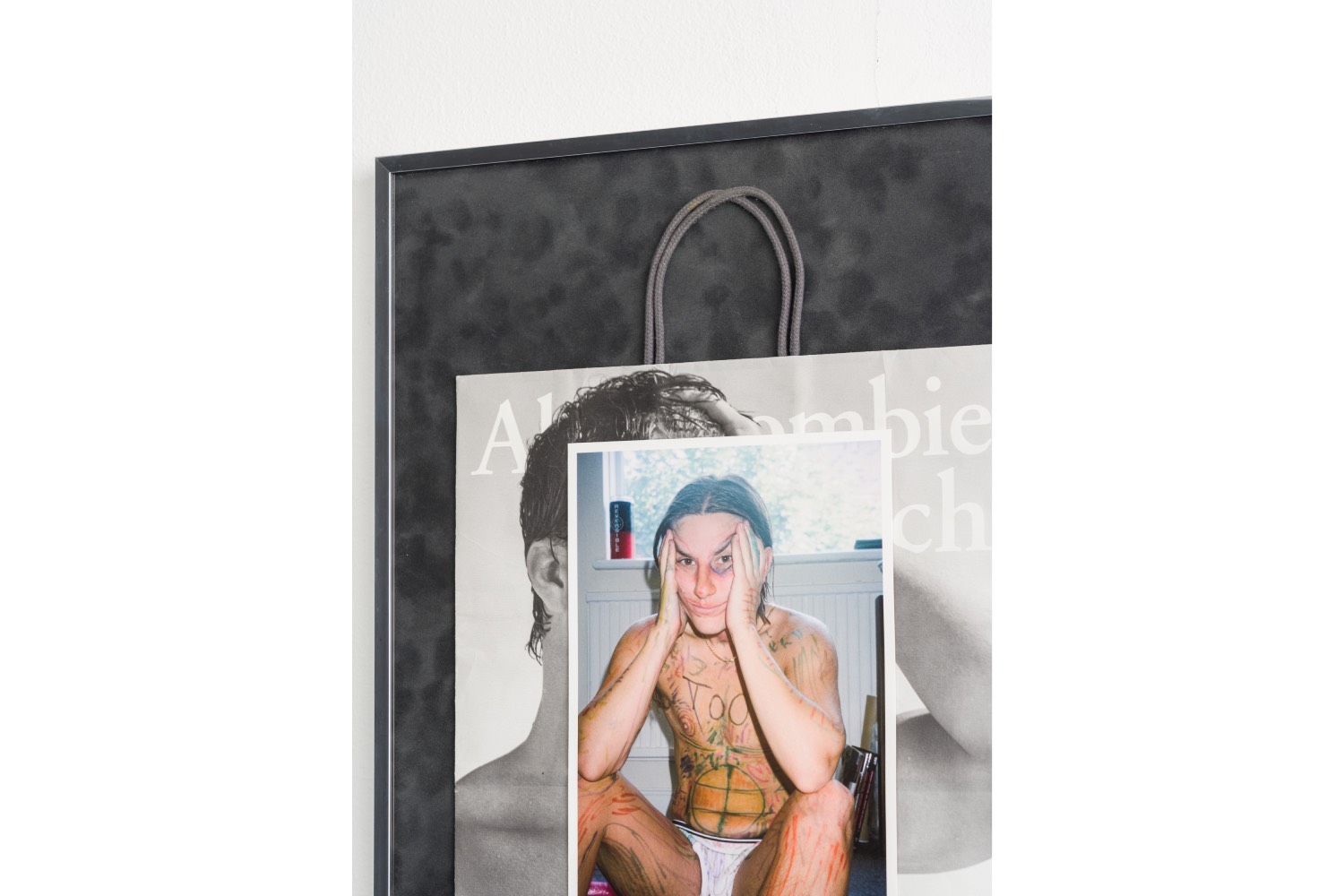

GW: We had to put cases around our schoolbooks. You could get store-bought ones or use paper, but there was also a trend of using Abercrombie & Fitch bags for them, which feels full circle. When making my own Abercrombie works, I looked up how to do it again and did a couple of covers. It was very satisfying; I want to bring it back. Those bags are so expensive now. I’m fascinated by these people who kept hold of them for twenty years and somehow knew they would be worth something. eBay is another element of my process and practice, actually. I’m curious about it as an alternative speculative market with its own set of possibilities and limitations, thinking about what I can or can’t find there.

PE: Do you see yourself as a collector? This is also an idea explored in your book One Hundred Baseball Cards (Baron Books, 2022).

GW: I put a couple of clippings that had sentimental value on the collaged paddle works. I’d been holding on to them for eight years. I even brought them to London when I first moved over from Los Angeles, but I wasn’t ready to use them. It’s also kind of humiliating that I have these little piles of scraps of paper that I’ve cut out that I’ve had a years-long relationship with. It’s about chance, too. With baseball cards, you buy them in a pack, so you don’t know what you’re going to get. Even with the porn magazines I order online, you only see the front cover, and you won’t know what’s in it, so there’s an element of surprise. I’m interested in how objects, particularly fetish objects, are imbued with another power or another meaning. That’s the same with collage, where the image already has another life or a symbolic resonance, and the artist’s role then lies in recontextualizing that through these acts of juxtaposition.

PE: Collage also seems to lend itself perfectly to the logic of sexual fetishism, a phenomenon in which objects become overvalued with erotic significance.

GW: That’s my practice in a nutshell: overvaluation. I’m also attempting to cover my tracks so other people could have a completely different reading of the work.

PE: There’s a generosity and a porousness to your work, which allows for a multiplicity of interpretations. You’ve spoken about the psychic structure of ambivalence in relation to your practice, but I was intrigued by other psychoanalytic concepts. These were evident in the curatorial text for the “Motherboy” exhibition you organized at Gió Marconi in Milan. However, in contrast to Oedipal structures, one aspect I was thinking about was how the lateral social axis and horizontal group relations are staged in your work. These dynamics also underpin psychoanalytic writing on war and violence.

GW: I think the concept of the lateral is an interesting way to talk about the doppelgänger theory that’s explored in the “Fratricide” show: what it means to look at the other to look at yourself. I want to create a space in which viewers might question their position. How do they identify with a certain space? Do they feel a sense of inclusion or exclusion? We’re constantly subjected to environments, architectures, and policies that enact these questions. The world’s real social, symbolic, and historical reality informs our internal perspectives.

PE: I have no experience of being a frat boy undertaking a hazing ritual, for example, but I have lived through other perverse and performative experiences of gender, such as going to an all-girls school.

GW: Totally. It’s funny as I also have not had the experience of being a frat boy. So, I’m already making a fantasy or projection. I keep finding old drawings I gave my mom where it seems I’ve always drawn muscle men; it’s never really changed. Earlier in my career and life, especially earlier in my transition, for example, I felt that the frat boy was low-hanging fruit in the culture. I’m still figuring this out, but I’m analyzing and exploring things, letting them be strange just by virtue of what they are, and allowing myself to make these connections rather than just saying, “I didn’t have that exact experience so that’s not for me.” So many of the experiences of being trans are also about being a person and being in a body, or feeling different from that, and just being a body in space. It’s nice to feel like I’m still finding a way to talk about the universal while being specific. I think the best way to get to universality is to come from a specific place confidently.

PE: This also returns us to those questions of inclusion and exclusion. A lot of your sculptural work draws on aspects of hostile architecture: appropriating and utilizing spikes, barbed wire, and fences, which creates a sense of anxiety and alienation.

GW: I’m interested in the mythology, lore, and representation of semi-public spaces and the blurriness between the public and private sphere. So, at the ICA, this was the notion of the bunker and war room. We’ve never been to these spaces, but we can visualize them due to the plethora of cinematic representations. In making that exhibition, I really had to face up to what it means to be from the United States — our history, present, and future — and how our mythology is very much entrenched in imperialist and militaristic violence and control. The wire, fencing, and gates are all ubiquitous because these are man-made objects and environments, but they’re also informed by and part of the zeitgeist in terms of cinema, art, design, fashion, and even thinking about costuming and the performance of military training. It’s all connected. Many technological developments have been advanced and propelled forward by their military use. To go back to the idea of the double, I was looking at the performativity of Cold War espionage and how this notion of playing roles might intersect with questions of queerness and society, such as the Lavender Scare. It’s about costuming, dress-up, acting, identity, and intimacy, which are all great examples of the lateral axis you’re talking about. I was thinking about how postwar sociology and deviant studies led to the contemporary landscape of queer studies, which is really fascinating, the Ouroboros of cyclical relations. The world is so strange already, and it’s a delicate balance. Still, instead of imposing a limited scope or a didactic narrative, one approach is just to let the weirdness exist: to give it space and room, including all the loose threads and the untidiness.