“Chryssa & New York,” currently on view at Dia Chelsea, marks a homecoming that is both institutional and personal. Although widely known for its iconic upstate branch in Beacon, New York, Dia’s history is rooted in New York City, where it was established in 1974. It is also intertwined with that of the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas, as one of its founding members, Philippa de Menil, is the daughter of the renowned art collectors John and Dominique de Menil. That this exhibition is co-organized by Dia Art Foundation and the Menil Collection is significant in and of itself. However, it is even more auspicious considering that this first comprehensive survey of works by Greek-born artist Chryssa (1933–2013) was inaugurated at an institution whose name comes from the Greek word meaning “through” — emphasizing its aim to serve as a conduit through which artists can realize ambitious projects — and in a city with which she had a meaningful creative and personal relationship.

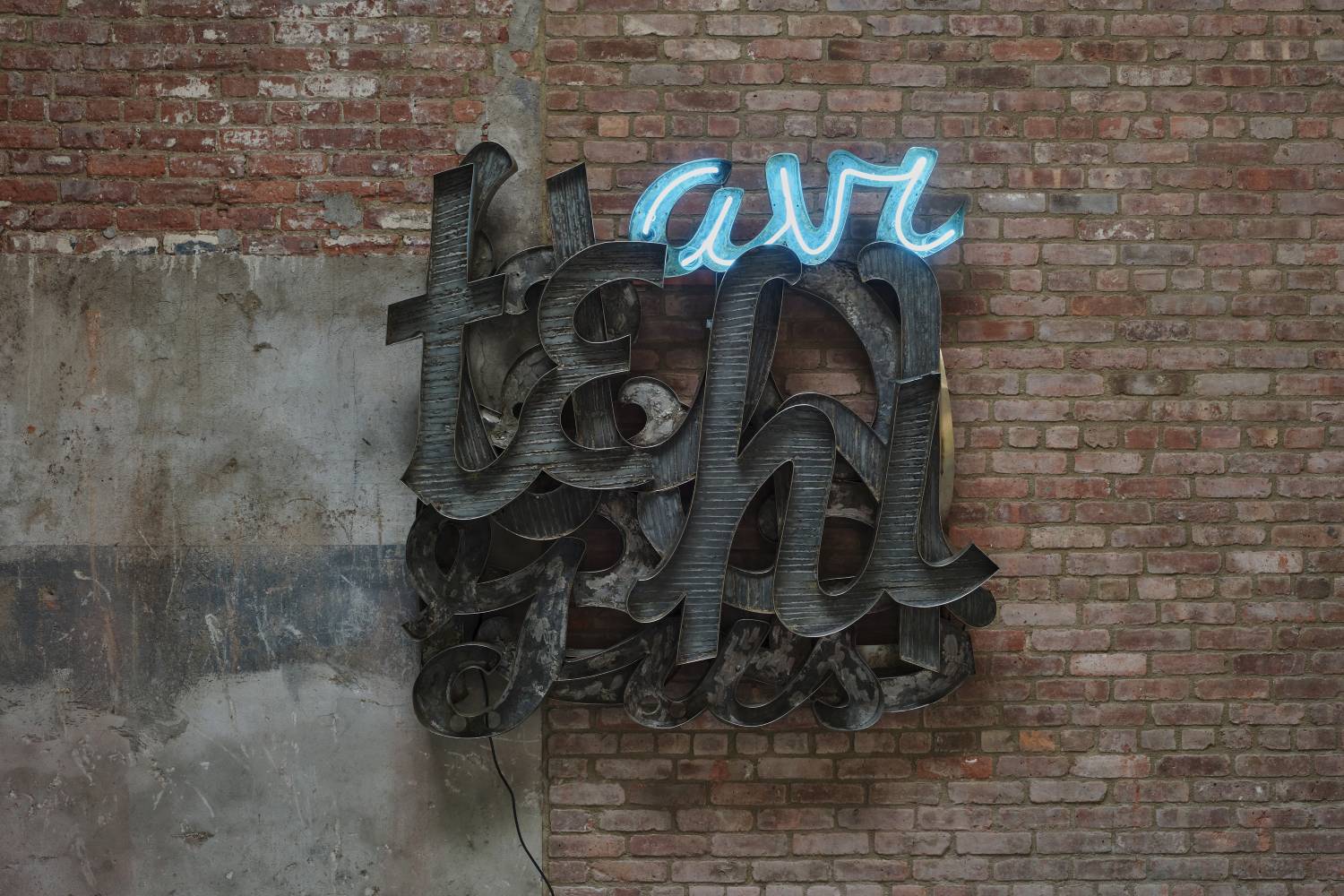

Chryssa arrived in New York City in the mid-1950s and spent a significant amount of her career there. It was in the bustling metropolis that she first encountered the site that inspired what is arguably her most momentous work, The Gates of Times Square (1964–66). Composed of cast aluminum, stainless steel, neon, plexiglass, paper, and found objects, this impressive sculpture speaks to the artist’s unique approach to material, language, and form. While The Gates of Times Square most clearly pays homage to the New York landmark that has historically drawn crowds from all over the world, it also nods toward other famous international passageways, including Hadrian’s Arch in Athens and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise in Florence. It references more abstract forms of movement and passage as well, most notably that of communication. A large letter “A” is composed of smaller neon symbols that illuminate the entire character in blue, and is enveloped by aluminum signs that form an overall cubic structure. Coupled with the inclusion of haphazardly rolled papers, reminiscent of scrolls of newsprint, The Gates of Times Square references some of the most basic elements of communication, from early forms of information-sharing to those brought about by the industrial revolution and more modern technologies.

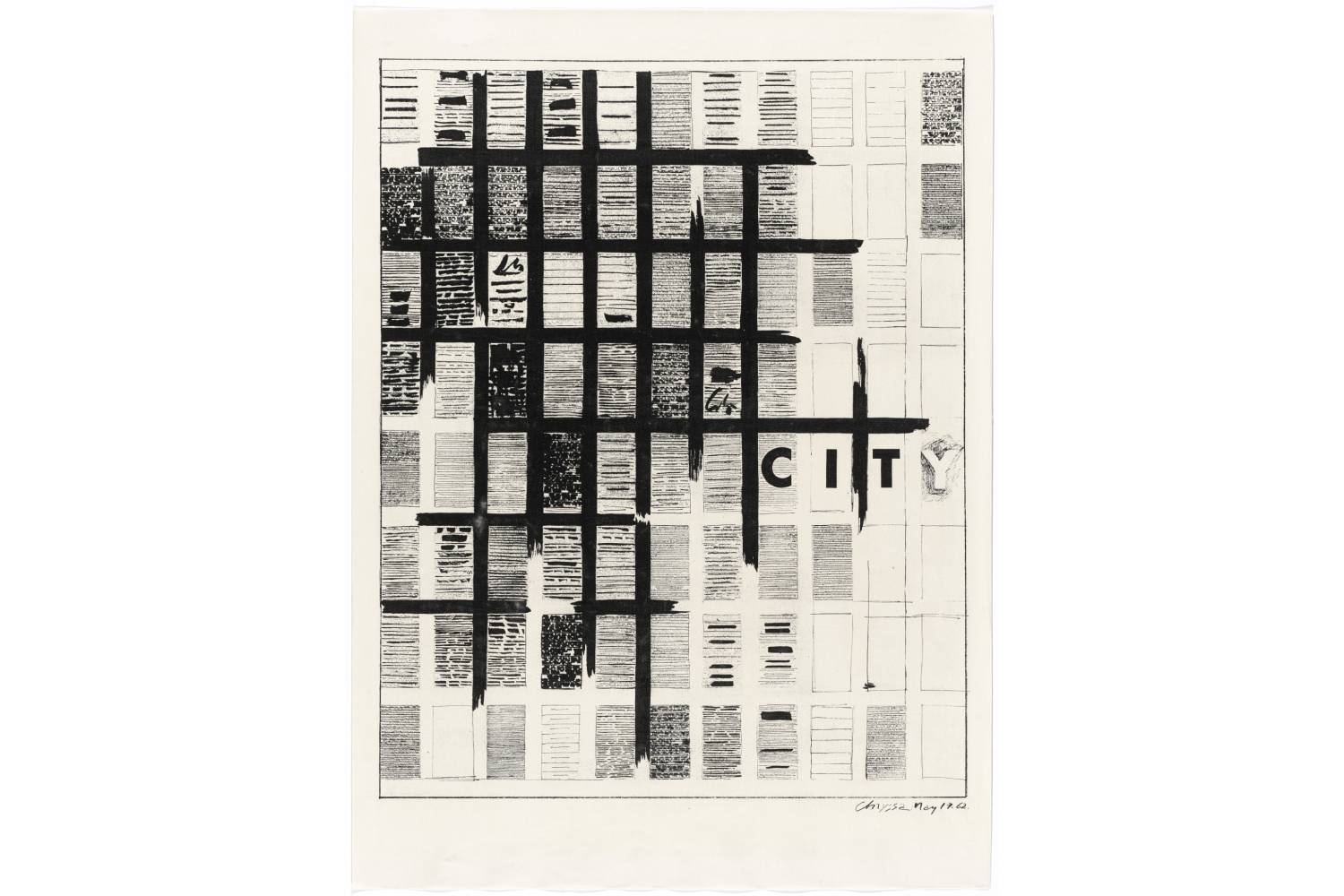

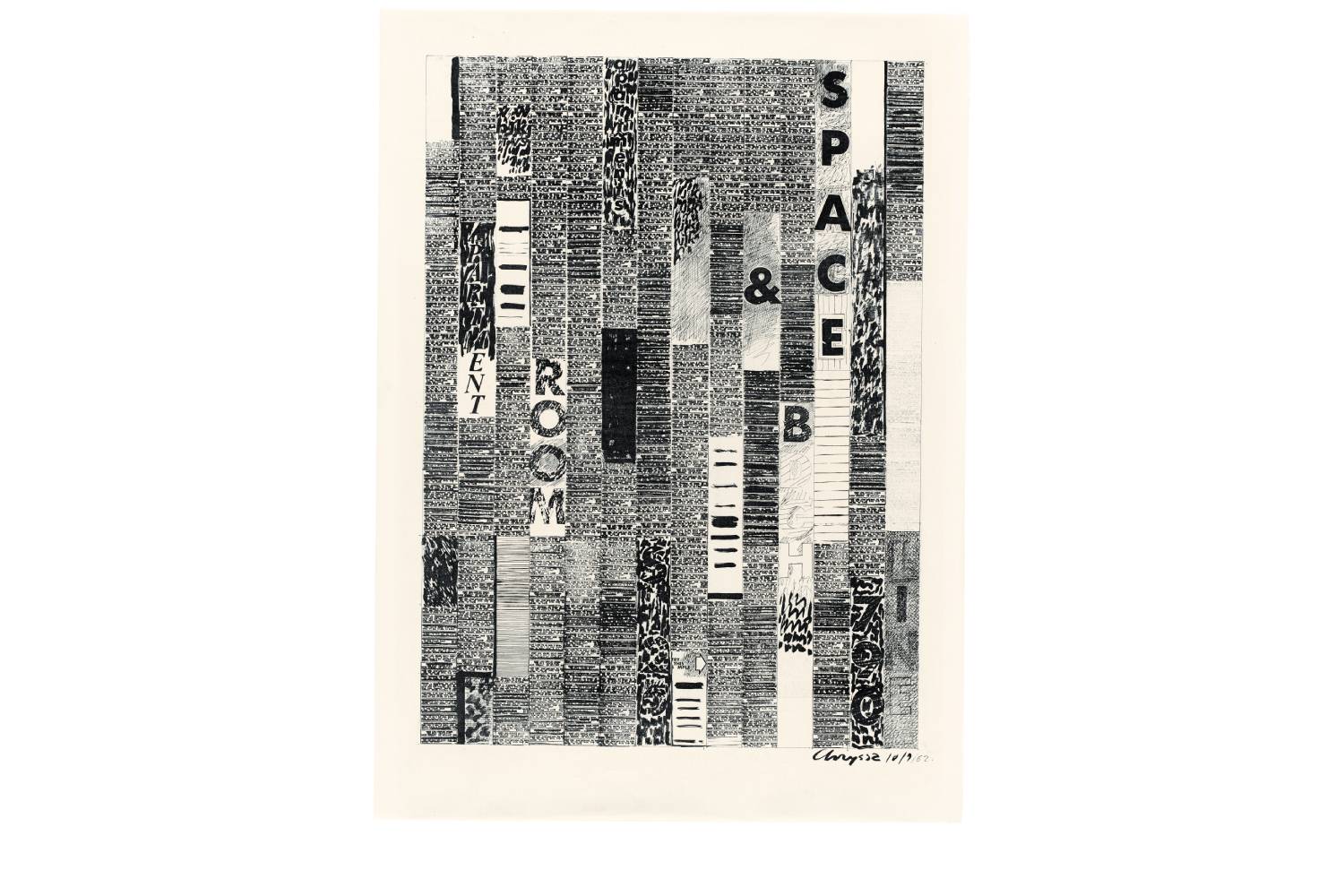

In the presentation at Dia Chelsea, curators Megan Holly Witko and Michelle White highlight Chryssa’s long-standing interest in communication by choosing to greet viewers with the artist’s later creations in neon and to close the exhibition with a wide selection of her early works. Having seen the art Chryssa made later in life before encountering earlier examples from her practice, the viewer’s approach is strategically informed. Most notable in relation to The Gates of Times Square is the artist’s “Newspaper” series from the late 1950s. To create these works, the artist used linotype printing-press plates, discarded from newspaper publishers such as the New York Times, as stamps on paper or canvas supports. She was precise in her placement, repeating blocks of text in a grid format to mimic a newspaper’s schema. However, by covering the base layers of text with a seemingly endless number of overlays, the words become almost illegible, unlike those printed in the daily paper. Such obscuring of language was a visual trope that appeared in the work of many women artists in this era, in marked contrast to the overt textual statements painted by their male counterparts.1

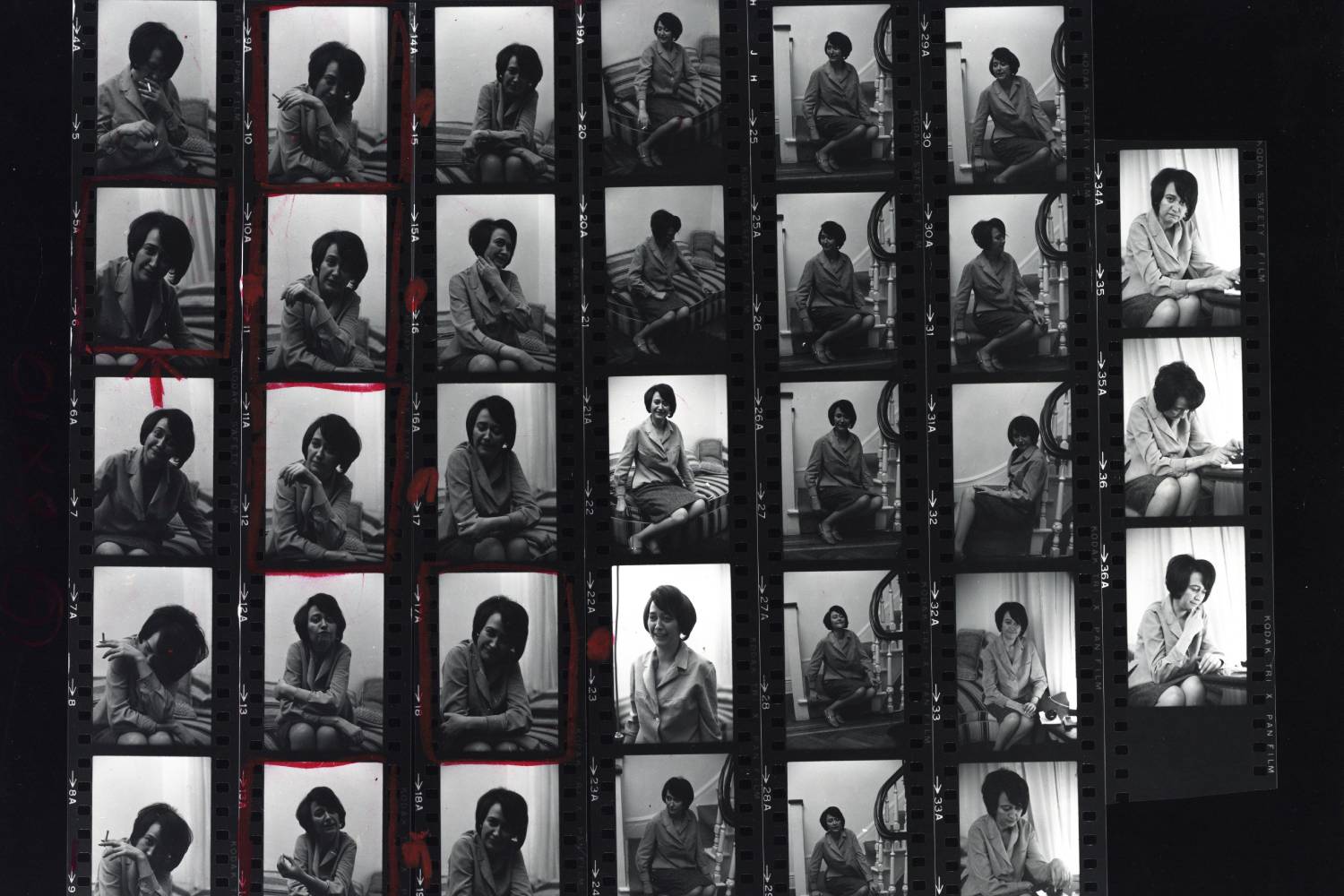

The last time such a significant exhibition of Chryssa’s work was staged was in 1982 at the Albright-Knox Museum. In response to why Chryssa’s work remains under-recognized, co-curator Holly Witko notes the delicacy of neon as a material that decays over time without use. Following her first solo exhibition at Pace Gallery in 1966, Chryssa’s work was acquired by several major museums and leading collectors, but many of her neon works in institutional storage deteriorated over time, leading to conservation issues. When embarking on this exhibition — a passion project for Dia’s director, Jessica Morgan, who advocated for unearthing Chryssa’s work from storage for inclusion in “The World Goes Pop” at Tate Modern in 2015 — the curators started from the signal piece they knew they had to exhibit: The Gates of Times Square. Quickly identifying its need for restoration spurred the undertaking of the major conservation efforts that made the exhibition and its union of such a broad range of examples of Chryssa’s artistic production possible.

At Dia Chelsea, the breadth and depth of Chryssa’s practice along with her innovative approach to medium and material are palpable, especially within the rugged, industrial setting of the institution’s galleries. The curators hope the exhibition will inspire new scholarship on the artist and bring Chryssa’s name to the forefront of conversations about the vibrant New York art scene in the 1950s and ’60s, in which she played a key role.