What do you dream of

When life’s not given?1

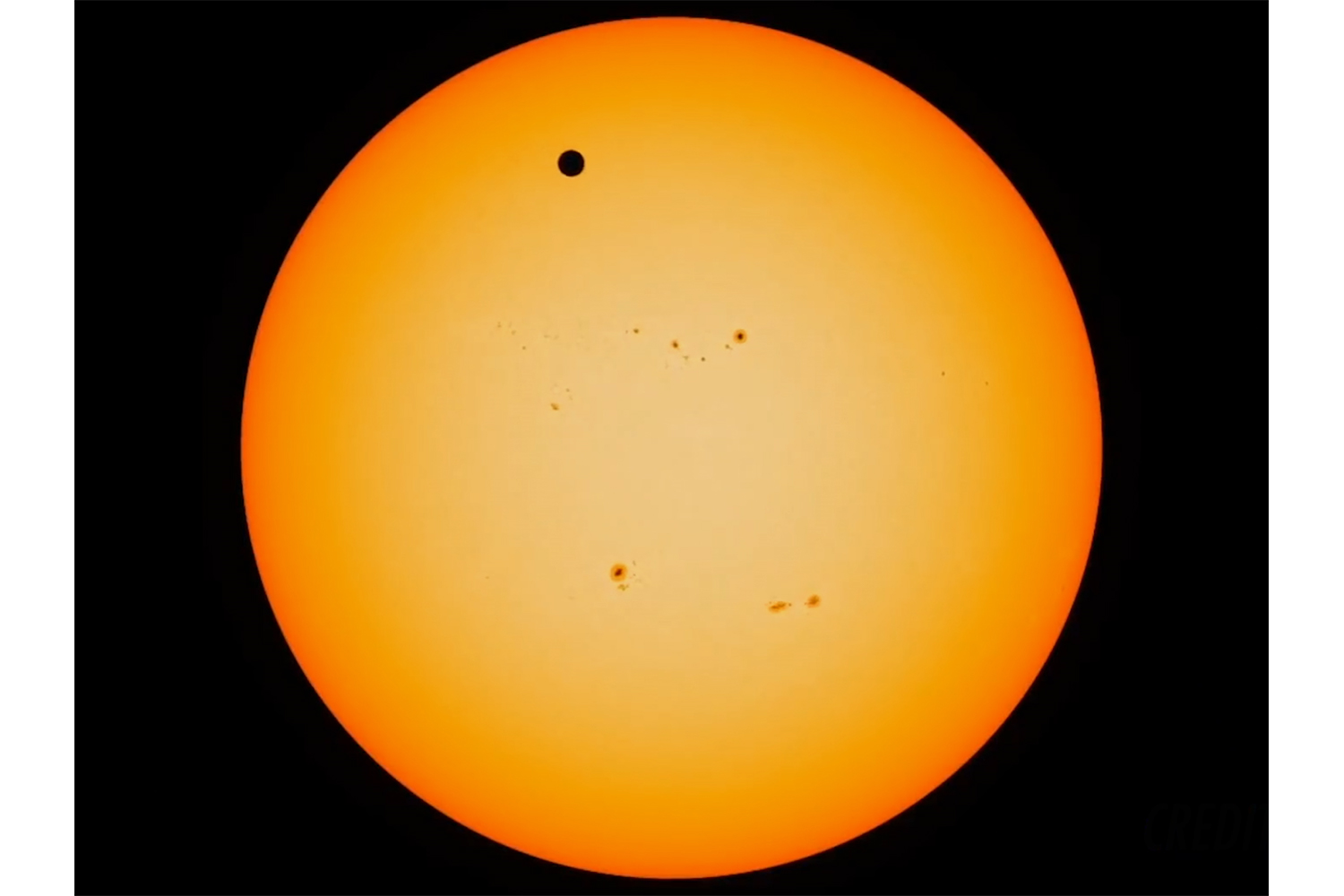

Venus crushes. Peony-dense, obliterating human experience in compacted flusters of sheer damage. Rains burn. Sweating, sure. Light straining, an aeriform muscle. Allover orange. Once, the surface water vaporized, lilting and leaking slowly into space: a saline release. Eternally razing, Venus is severe, stellate and denticulate with crunched mountains tremoring in unknowable mass. Scrutiny withers into imagination’s snowish ether. Scotoma. Its deep- water pressure is denting, disarranging. Penetrative, a load of concentration dilating from inside. Girth, flourish. Clouds of sulfuric acid roil in lead-melting laceration. Sunlight-scattering, they fold heat upon heat into a hard, loaded white. Rotating backward incandescent and shoreless, near-death purls forever. Turbulent, irreducible, brutalizing, and churning … finally — yes — like feeling.

on venus

we are neighbours

in nerves / 2

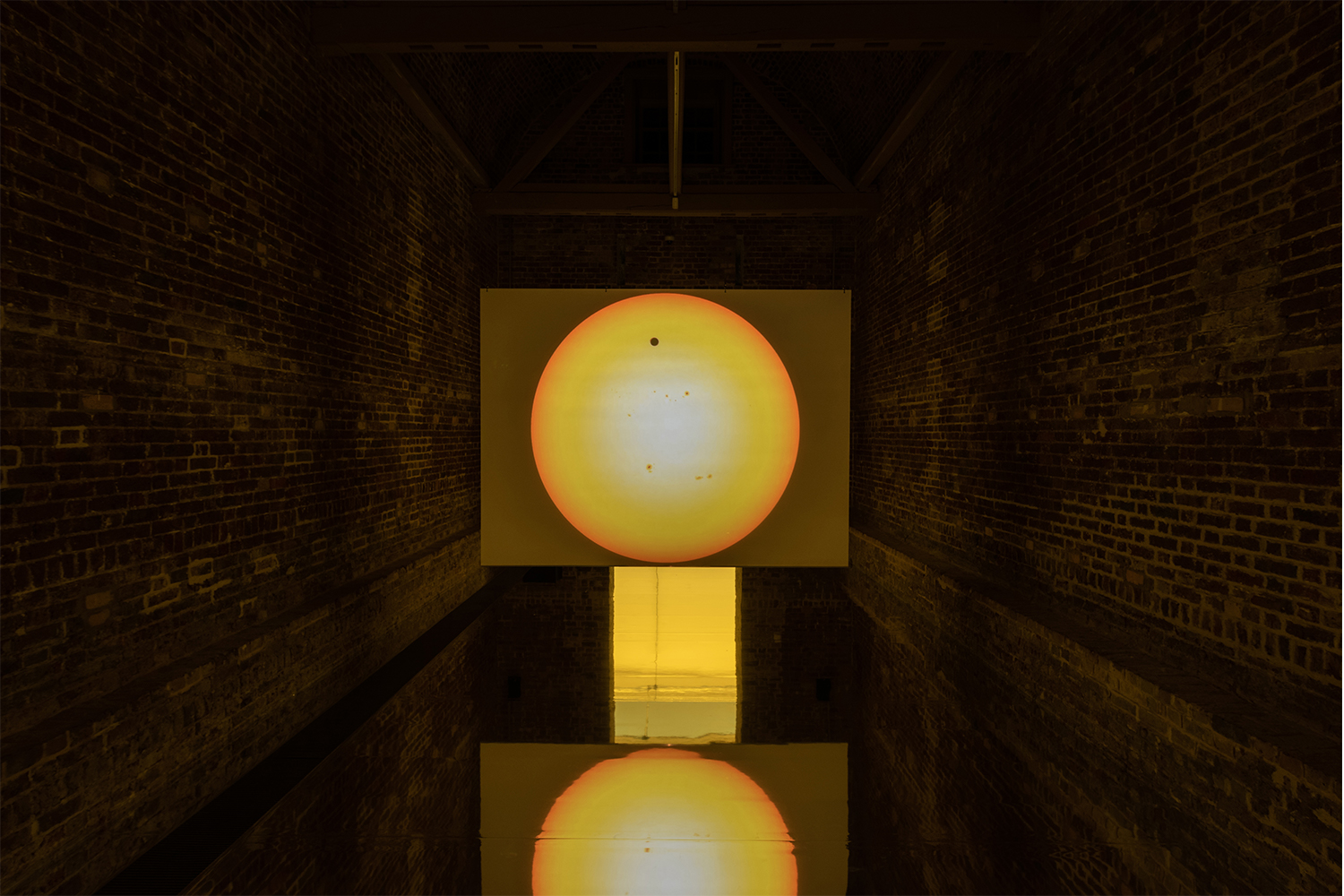

Depth was extinguished in the bathing immersion of fluoro-yellow light in P. Staff’s On Venus (2019). Alarming and suffusing, dilatory and dreamy; like chemiluminescence: fantastic toxicity. Reflective flooring exposed the sensory collapse, as if everything had swallowed itself. Strangely weightless and suspended — “awake, breathing,”3 as Johanna Hedva describes this yellow — it also emanated the “grave” in that gravity felt present in an unusual way, as though levitated, leeching and drawn into things. The sour-honeyed contaminate of its warm artifice conjured the bodily, its full-on flush of the gaggy and vomitous, osmotic and putrescent.

Everything within and passing through temporarily captured in piss-soaked amber, never to ramify into resin. Defanged felt the architecture of the Serpentine Galleries, the location of the site-specific work (November 2019 to February 2020), with the ceiling sweltering the lacteous arsenic of its envenomed atmosphere: a network of pipes channeling the leakage of corporeal and synthetic acid into large, polished steel containers.

This acrid quality of light made formidable the stealth saturation of Staff’s incisive violence-as-ambience. The haunting fervency of Staff’s installations are a more recent development and will form a sense of their newest solo exhibition, “In Ekstase,” at Kunsthalle Basel. But their sensitivity to the constitutive force of violence in the making of a person is a constant, often resulting in penetrating and fluxual states across forms that bleed, irradiate, pool, splinter, and corrode. Erotics are its seething substrate.

External appearance and internal states — of love, of suffering, of passion, of resilience — intoxicate and deliquesce one another. This sensitivity is attuned to and embodied by the hypervigilance, sensorial awareness, and dissociation that resonates with transed and cripped methodologies. As Hedva writes, “It’s the premise that dysphoria is an ontological condition.” Staff’s work acknowledges that “dislocation […] is simply the default.” The violences to which Staff is attuned — biopolitics, necropolitics, the medical-industrial complex — are rarely isolable;4 though displaced or refracted at varying degrees — in half-awake reveries or celestial bodies — they silhouette and orbit the work, shadowing images, objects, and atmospheres.

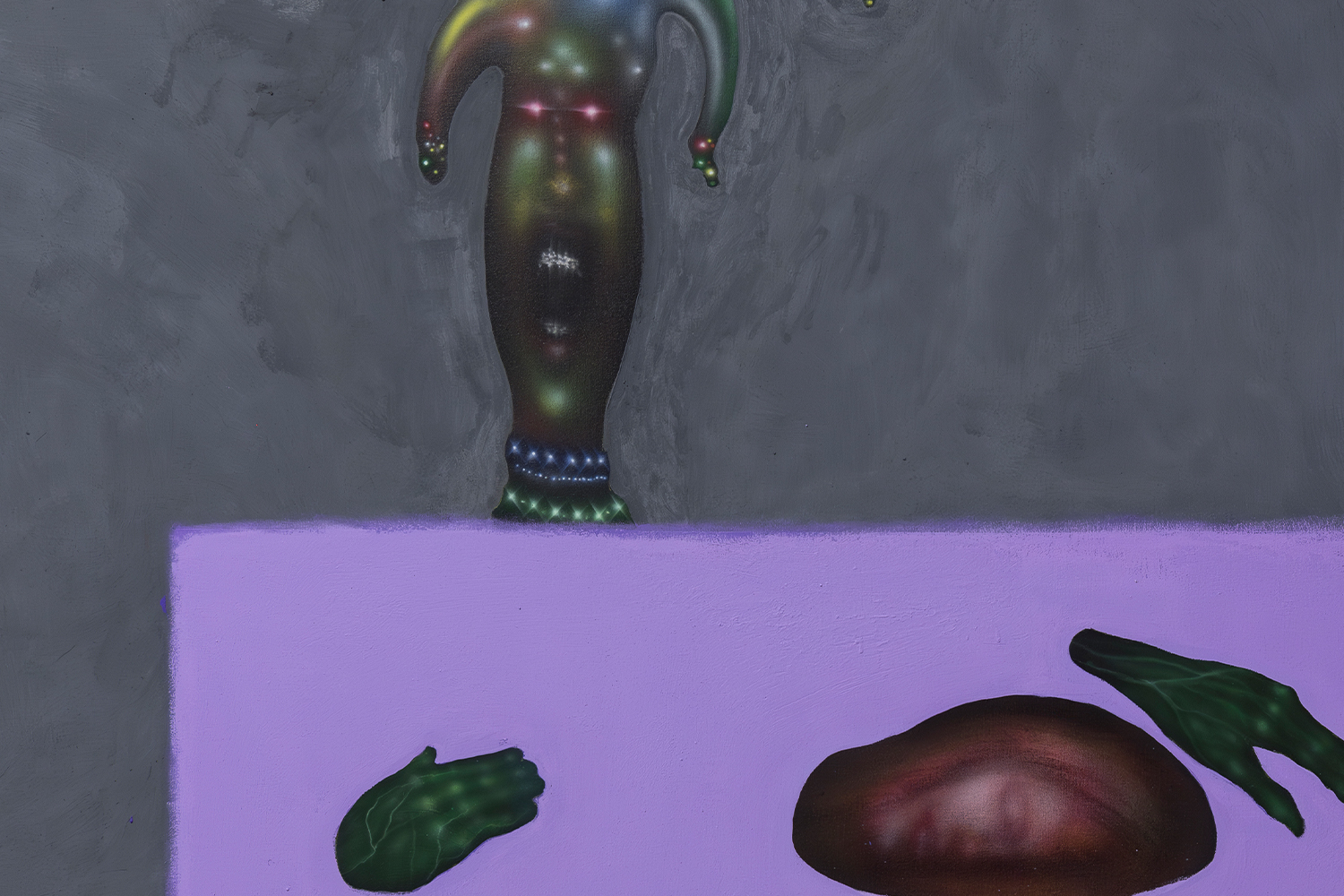

The metaphorical emergence of Venus is devastatingly articulated in the video On Venus. Life on the sister planet is strategized as a state itself, an equivalent locus that Staff describes as a means to address “parallel forms of life, dispossessed living, or ulterior states of near-death, non- life, non-death.” On Venus initially shows footage documenting the industrial farming of hormonal, reproductive, and animal commodities: semen, meat, urine, skins, and furs. Everywhere is the spectral ontology of the commodity perversely animalized, automatedly abstracted and routinely drained of life.5 In throbbing, disjunctive, and inverted colorations, the brutality is nearly impossible to parse — animals and reptiles are skinned alive; unbearably, a dissevered heart lays beating — the chronic abuse simmers within, unrelieved. Staff does not reduce this industrialization of animal life to cohere some anthropocentric integrity or blunt moralism; rather, the work dwells in the inherent imbrication of human and animal entanglements with race and labor under capitalist extraction.

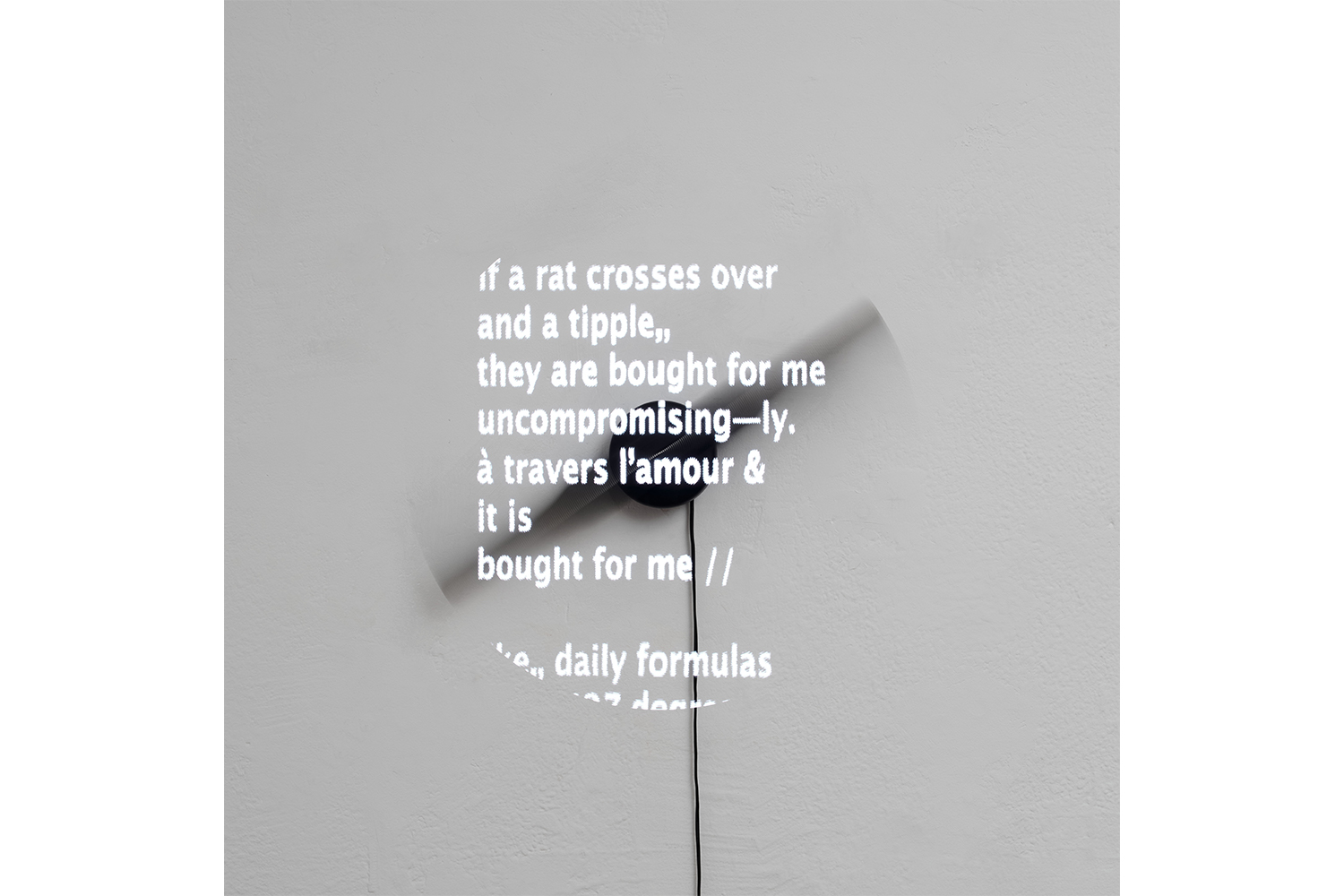

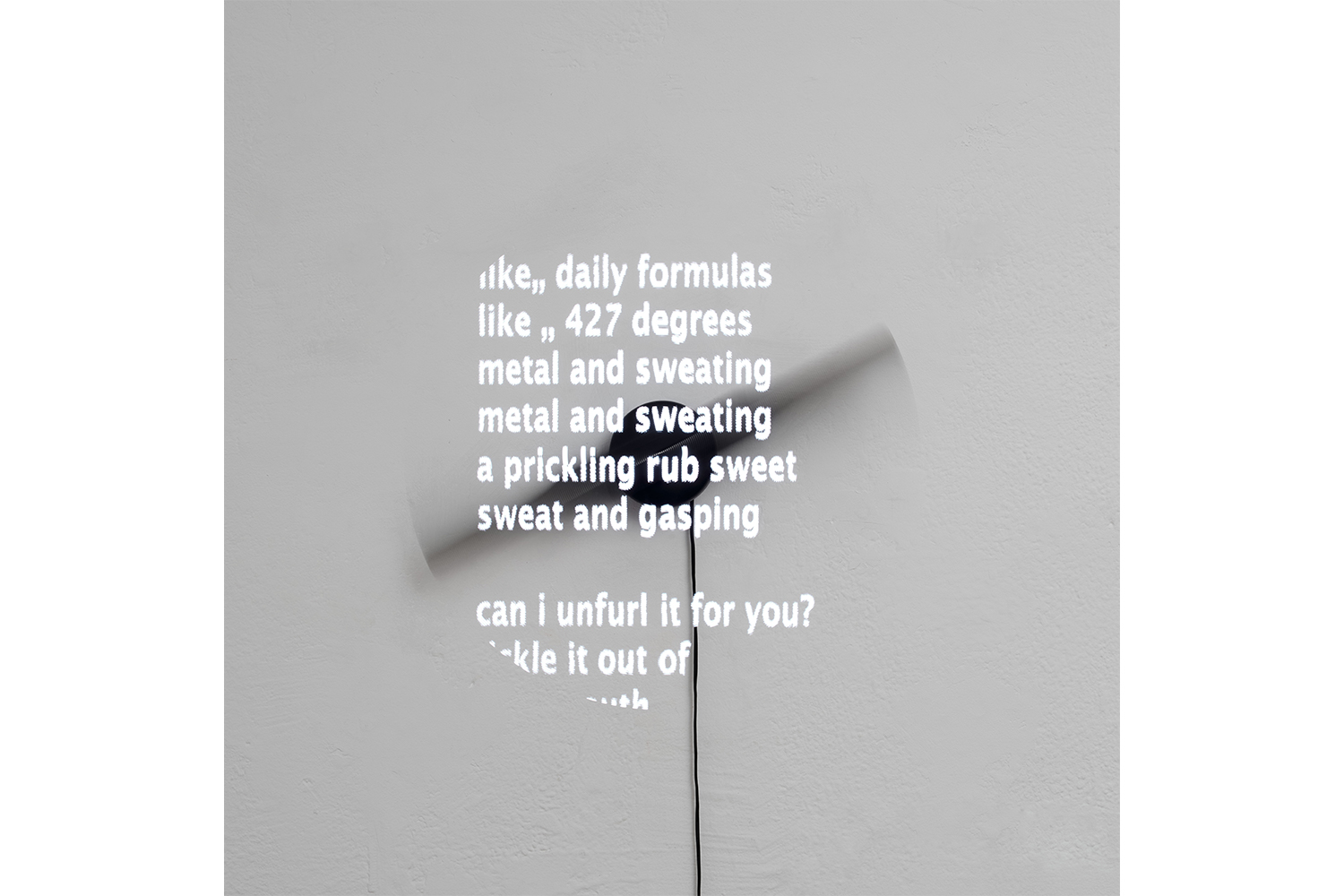

The second half renders the materiality of film, scratchy and filamentary with shivery physicality — like dead skin, pubic hair, dust motes — before multiplying pressure as a poem articulates life on Venus. Light strikes percussive with blinking rapidity, each flash a chatoyant shock. Sounds akin to accelerated helicopter blades; with metronomic clicking, pulsing; with deranged whirring, quickening.6 Language accretes to a beat which calibrates a sense of torqued ascension and vertiginous deformation while the poem’s force hemorrhages a sense of aliveness, collapsing senses and dematerializing forms; bleeding, inverting, in its escalating rupture the cadence almost conflagrates. With every viewing, I am heated.

Staff’s body assumes primacy as a dysphoric prism through which to interrogate institutional logics and conditions. Through this lens, the subjectivation of such power becomes a reservoir to feel through, sensed and shaped across felt-body knowledge and their dimensions of pleasure, violence, pain, desire. Moods of lethargy are reserves of voluminous queerness, challenging capacity and, as antithetical to production, invoking transgression: exhaustion, sleepwalking, inebriation, nocturnality, a fogged sense of being fucked-up. Oftentimes this is enhanced by choreographic tactics whose phenomenological readings erupt or deconstruct the institutionalized sovereignty of space. As a site for tracing the hypersensitive terrain of lived, somatic experience, this queer and trans body resonates with Eva Hayward’s interrogation of “transposition.” Hayward articulates transposition as “a deviation that discomposes order […] equally destructive [and] generative.” Reading sexual transitions with spatial orientations, “forces and excitations of location,”7 Hayward asks: “How do urban forces accompany transsexual transitions […] that shape and reshape a neighborly self? What is the somatic sociality of transitioning?”8 In this, Hayward reads spiderliness alongside the transpositional. The spider’s web is a homespun territory manifested within the body, an extrusion of the organism into a gossamer reticulation and fleshly habitat.

Hayward likens this webbing to a logic of “extending bodily substance through sexual transition,” concatenating transsexuality as “an arrangement between the sensorial milieu of the self and the profusion of the world.”9 One’s responsiveness with an environment sets the conditions of one’s emergence. Staff’s synthesizing of their trans body as lens and liminal medium bridges this hypersensitivity, leaking self into world, and world into self. Precisely in the precedence of this dissociative engagement does one navigate the fierce, prickly absorbency of Staff’s work: a haptic entropy that is acutely organic.

Hayward’s thinking about sensorium and space through the energization and incitements of bodily limits aligns with the creative reactions of Staff’s materials, namely the use of bodily fluids or synthetic versions of corporeal acids. In Love Life (2022) at Sultana Gallery, Paris, with a later iteration, Love Life II (2022), at Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, Staff filled glass bottles with a simulation of stomach acid: hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and deionized water. Strewn beside walls, the vessels are wasted remainders mellowing in the crapulent afterglow of a previous night, but the wet potential of this residue effects yet more ruination in its volatility. Heavenly hellish like Mars, revelatory like a rosebud, or alarming like an aposematic blush, at Commonwealth and Council the bottles formed part of the red-washed installation On Gravity (2022), featuring a sequence of black pedestals with bottles decorating their edges or occupying plush towels. All is efflux: the body beyond its limits, to sensuous infinities.

Yet the bottles suggest a closed loop of potential auto-pollution, returning virulent liquid through the system, contaminating in its circulation. Similarly, in the collage series Piss Boys (2021), gelatinous resin panels feature photographs of white cisgender men urinating into their own mouths, their self-consuming display — or self-swallowing dick energy — littered with friable debris: hair, ash, seagrass, gold leaf, fingernails, bones. Stretching inversions of pollutant and container, Love Life II included the acid-abraded barrels previously shown in On Venus, now flattened and flayed to display gradations of corrosion, each On Living, Still (2022) marked with temporary tattoos. In these details, between poor vision and scabrous rust, the miniscule silhouette of a mare appears, desiccated and ruched like a flake of skin.

On living, still. The comma in Staff’s title snags, holds “a state of unbeing,” which in its “still” suggests both a confrontation and continuation. Put simply, life does not begin in the same way, in the same moment; there are cosmologies in which life, too, can be continuous with death — a version of life itself. This lapse coheres with Staff’s practice, addressing how queer, trans, or disabled being comes into the world under the duress of organized oppression, of putting life in order. Attending to how life lives across such torsion, the work retains suspicion of contemporaneous empowerment discourses of community or solidarity — knowing the subtractive risks of exceptionalizing and “inclusive” tactics. It is in this challenging state that the work is charged: a vitalizing potency alert to the limitations upon a life, including the violences of life within “death worlds,” as Achille Mbembe writes of necropolitics: “[a] social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.”10

Across a seemingly everlasting crisis of sexual panic, Staff’s work renders (dis) continuous modalities of life and relationality of being under the governance, calculus, and category of death.

Dream a metal tongue–Pussy Boy11

Pain is inextricable from pleasure, as suffering is from endurance. Staff’s Love Life broadens queer desire to consider the dis- ease of insisting upon the ungovernability of desire more broadly. The titular series features black-and-white photographic collages, saturated in transparent epoxy resin — prolonged exposure to which can cause inflammation and, later, sensitization. The resin subsumes everything in its lethal preserve, meaning the list of materials might also include “hair” and “insect.” This alloying of materiality, including the accidental, is much like fucking’s discharge, the ecstatic smattering of sweat and spit, the eruptive rush of cum. But this lucent preservation is also artefactual and investigatory: case studies in which the politics of reading and looking become awkwardly deployed. Some photographs depict piles of skulls, others rats, arrangements of the acid-filled bottles, or cartoonish sketches of distorted tongues. The Love Life series generates unstable cyclicality as orifices meet openings, vermin thrive, and bodies skeletonize. Sometimes they break out in hives, surrounded by syphilitic circles or entoptic phenomena, a composition of immiscible liquids nevertheless held together in asynchronous viscidity.

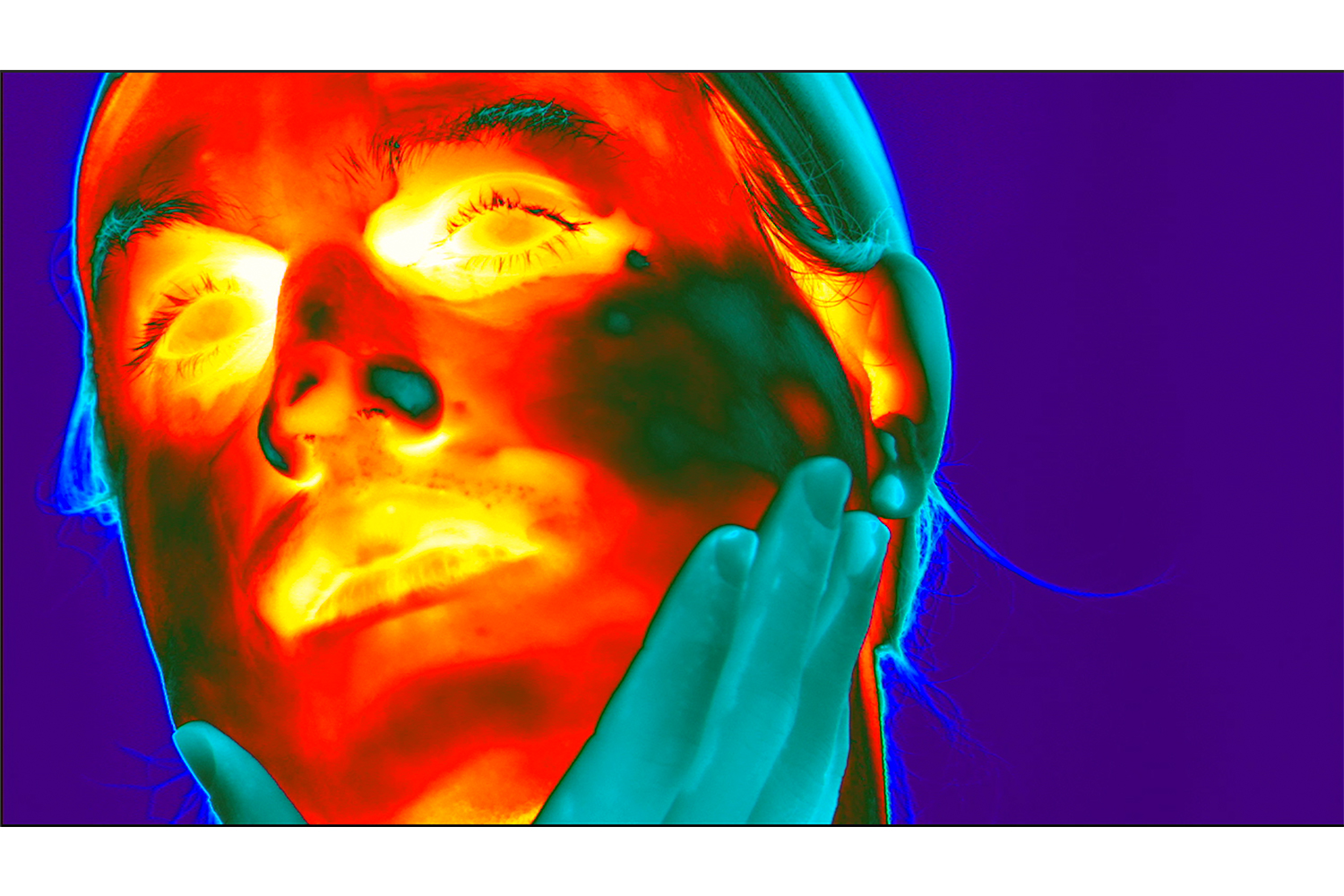

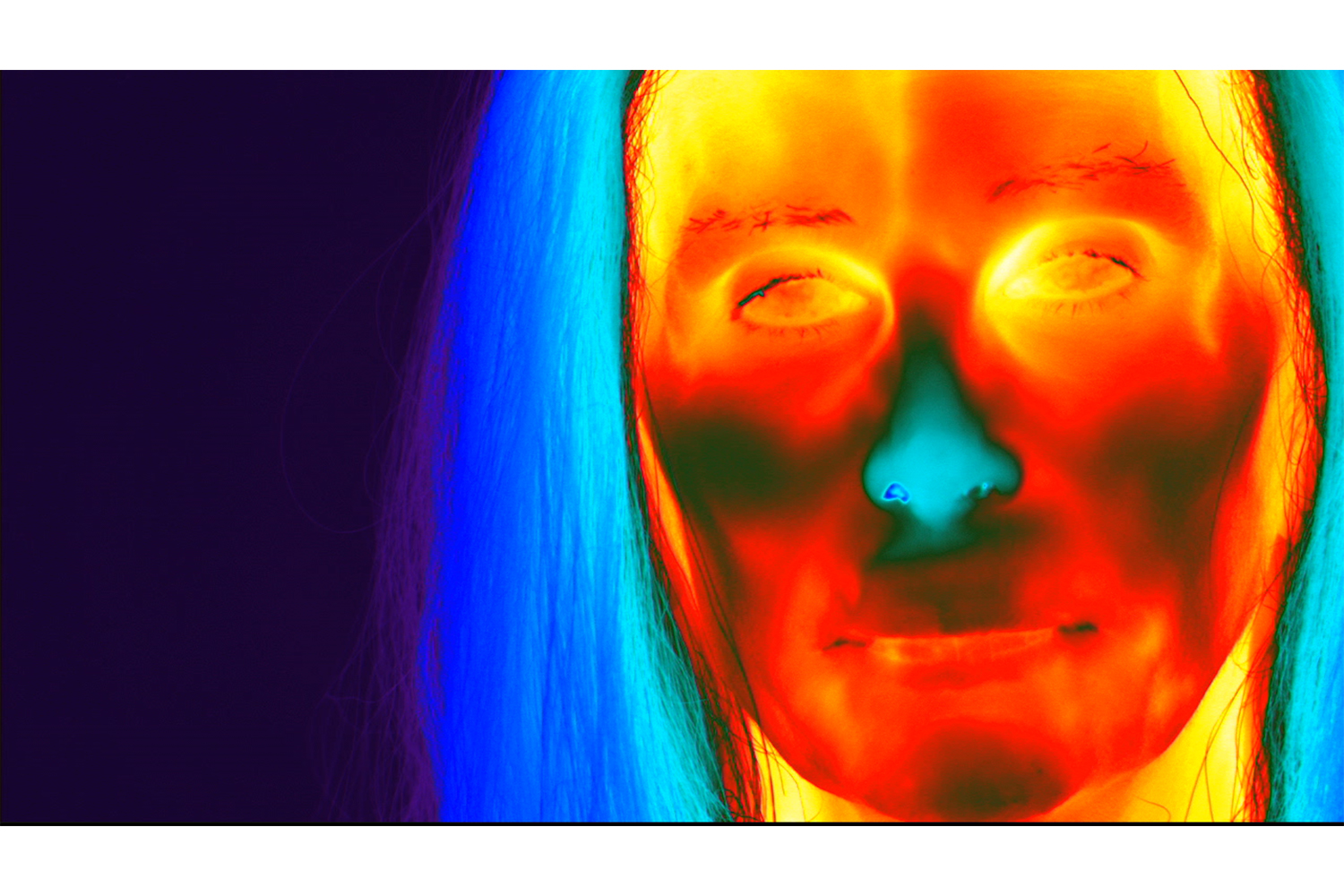

Staff’s use of hyper-sensual materials coexists with perversions of clinical technologies. In Staff’s video Weed Killer (2017), trans activist and veteran Debra Soshoux performs a monologue from Catherine Lord’s memoir The Summer of Her Baldness (2004), which reflects on the chemically induced suffering of chemotherapy. Placing chemotherapy and sickness in uneasy dialogue with one’s transness, the self-narration of Weed Killer is compounded by the curative/ poisonous embroilment of pharmacology as effected on screen through thermal imaging. In these surveilling visuals, the infrared captures and captivates at once with bodies and faces abstracted beyond the epidermal and irradiated into aching neon pools of heat, liquid, air. Aluminous skins, tenderly strobing. Hair strands of gasoline blues. Opening out these scopic regimes to sensuous force — exploring the experiences of loss and longing in relation to identity at the intersection of gender, illness, and contamination — Weed Killer reads the self-determination of endurance and emergence as volatile and always already impure.

This agitation of optical technology is also a reminder of how Soshoux regards the law. When relaying the anecdote in Staff’s temporally ruinous The Prince of Homburg (2019) — an anti-androcentric and sensorially stumbling revision of Heinrich von Kleist’s 1810 play about the revolutionary potential of dreams and dissidence12 — Soshoux defines the law as “a reflection of the consensus of a body politic at any given point in time.” Projective and reactive, the law is akin to a corpus in which any stress upon the surface fortifies the surface as such. The definition recalls Sara Ahmed’s analysis of hate, an emotion that circulates in an affective economy between signs and bodies, predicated on the movement of certain bodies where the emotion attaches, sealing others as objects of hate.13 An attachment of sustained expulsion, hate is indelibly intimate.

Knife, Scalpel, Blade (2022) comprises photograms of blades, knives, and axes bathed in mellow hues like the gradations of a lighter — yellow, orange, turquoise — irradiated as glowing voids into which irresolute conflictions and ambivalences are poured. At times installed as large grids, these morphologies of weaponry are mosaics, mappings, or portraits, where white-hot centers meet coloration in the searing of light. Their intrinsic stress is emanation. They call to mind the vantage point of injury amid myriad versions of living. Where does injury exist in the consistent spectacularization of death? What do discourses of the humane do when relegated to “gratitude” for not being killed? What life exists before the extremely constructed finite event of death? On pain, Ahmed writes of its formative qualities: “It is through the intensification of pain sensations that bodies and worlds materialize and take shape, or that the effect of boundary, surface, and fixity is produced.”14 Pain encourages the taking of shape while risking the fortification of a border, and yet to heal might require the risk of incremental exposure. Pain accretes a concentration which can be, at times, catalyzing. Healing and injury are constitutive sensations of the surfacing iridescence of a body, which senses the form it needs to endure. On Venus, then, is the imperative to burn immersively and gift an incitement to begin again:

LET THE DEVIL IN

LET THE DEVIL IN

LET THE DEVIL IN

LET THE DEVIL IN15