Marseille-based video and performance artist Sara Sadik is best known for her emblematic work on the Maghrebi diaspora in France. Rooted in the human condition, Sadik’s video-game aesthetics examine loneliness, love, and empowerment through the lens of a Muslim man confronted by societal prejudice and institutionalized racism.

Achieving international acclaim in recent years, Sadik’s uncompromising narratives portray a world at a crossroads between fantasy and reality, documentary and fiction. Her works are character based, focusing on individual protagonists: surrogates for her own friends, family, and community. I spoke to Sadik on the eve of her second performance at the French Academy in Rome: a continuation of her “Xenon Palace: Crystal Zastruga” exhibition on view at CURA’s Basement Roma. As we caught up, a light breeze clattered the shutters of Villa Medici. Behind her I could see the villa’s stone pines: an emblem of Rome, it was Mussolini who first propagated this species as a symbol of Italian dominance of the North African colonies to which the pines are native. The irony was lost on neither of us.

Ben Broome: I wanted to start by asking you about Émile– Samory Fofana, who is, on a personal level, your husband, your world, your rock. But your relationship goes beyond that; Émile-Samory is also your collaborator and your muse in a sense. What’s the dynamic between the two of you as partners and collaborators?

Sara Sadik: We met two years ago. He was acting in theater. He represents everything that I love on a personal and professional level, so right away I told him, “I want to work with you.” The first project we did together was Ultimate Vatos (2022). It took some time to figure out how we wanted to work together, and that first project was a bit of a test. I was doing the writing, he was doing the acting, but there comes a point where you have to draw a line to define who does what. The writing process is only me, but when I hand him the text he’ll say, “Okay, I don’t feel this part, I want to change it this way.” He gives me input on what he thinks as an actor and as my partner. It’s something that feels free and natural. I conceive all of my projects, and once I have the idea that’s when we talk together, we change things, we figure it out.

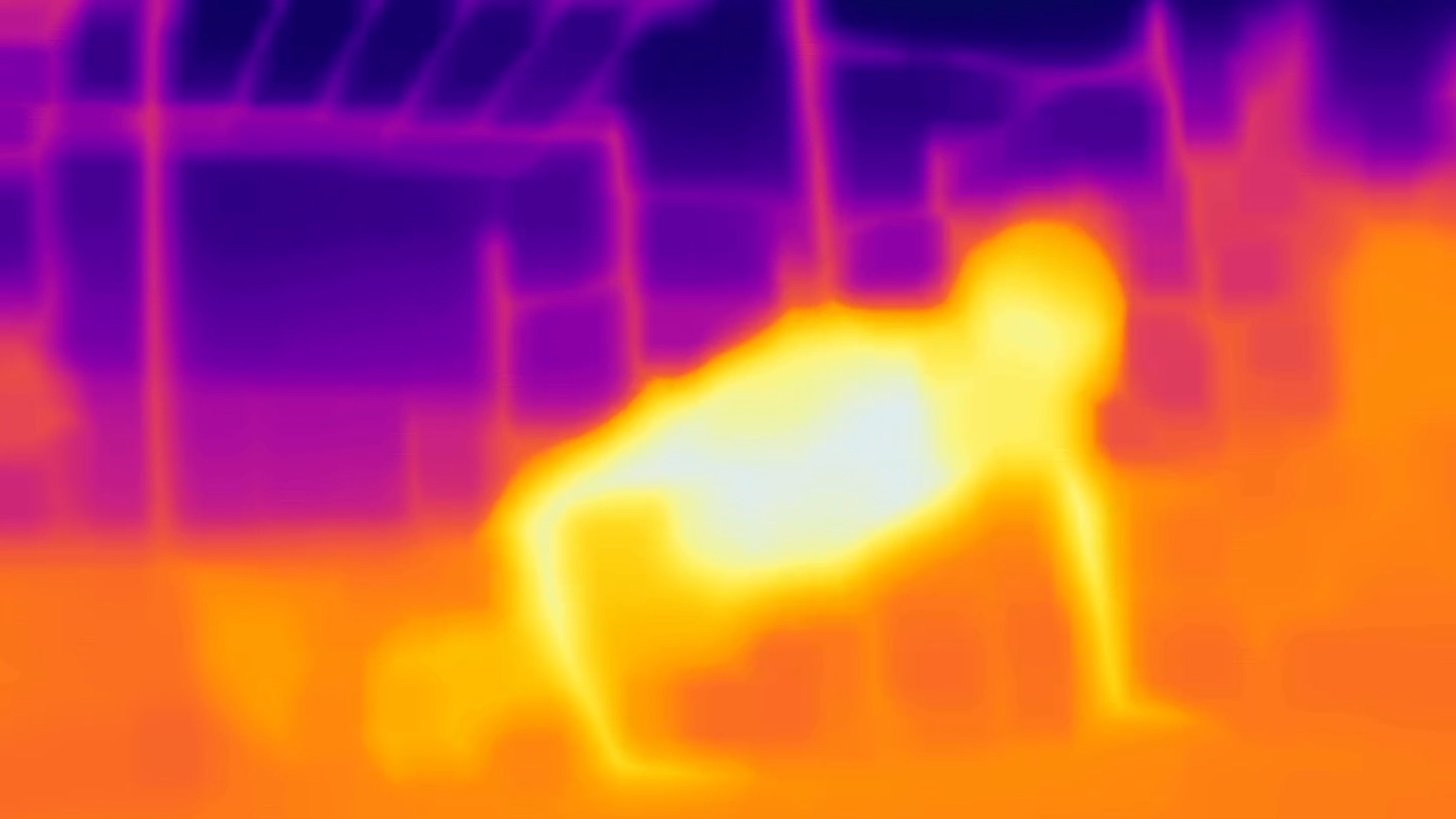

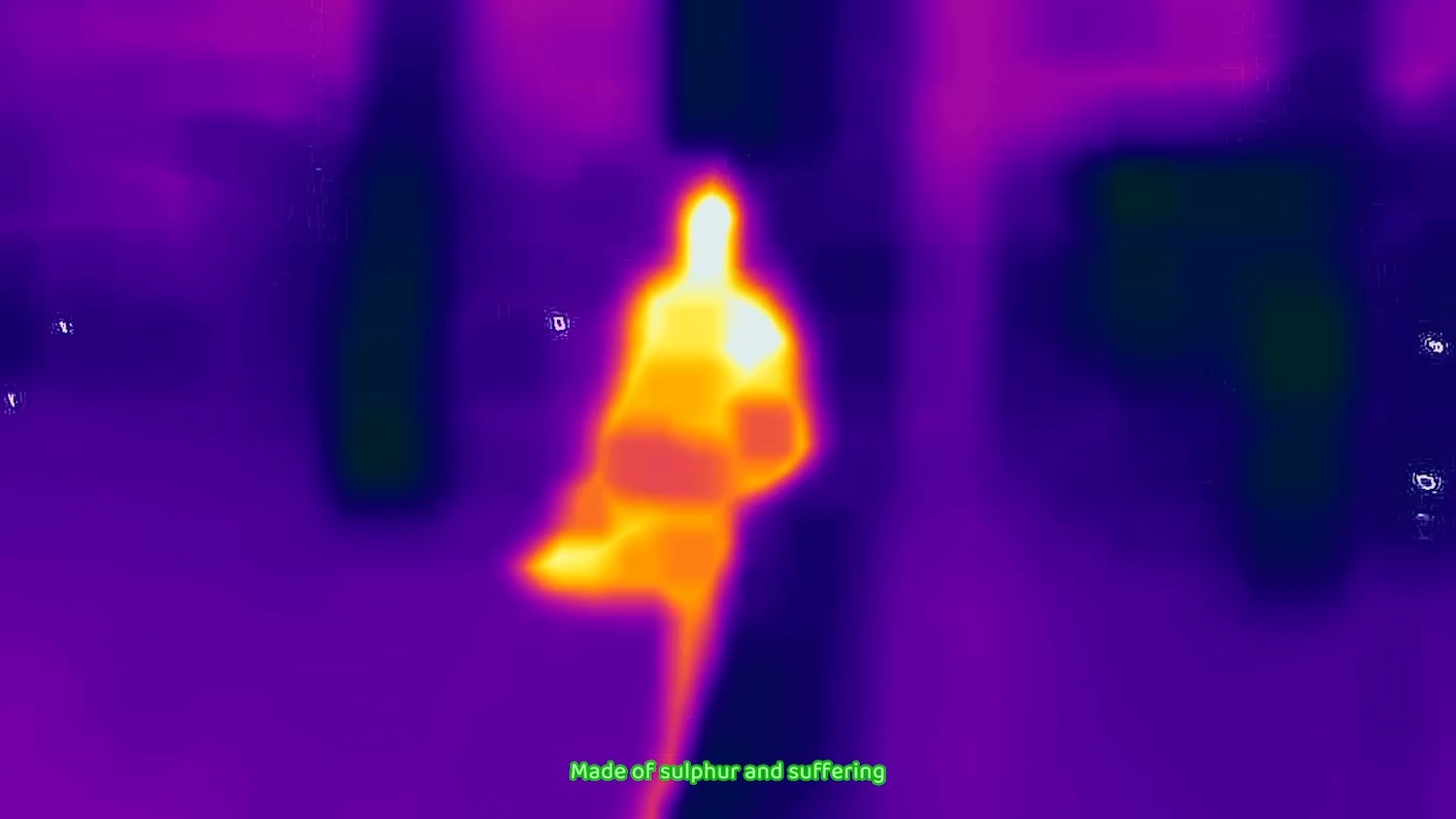

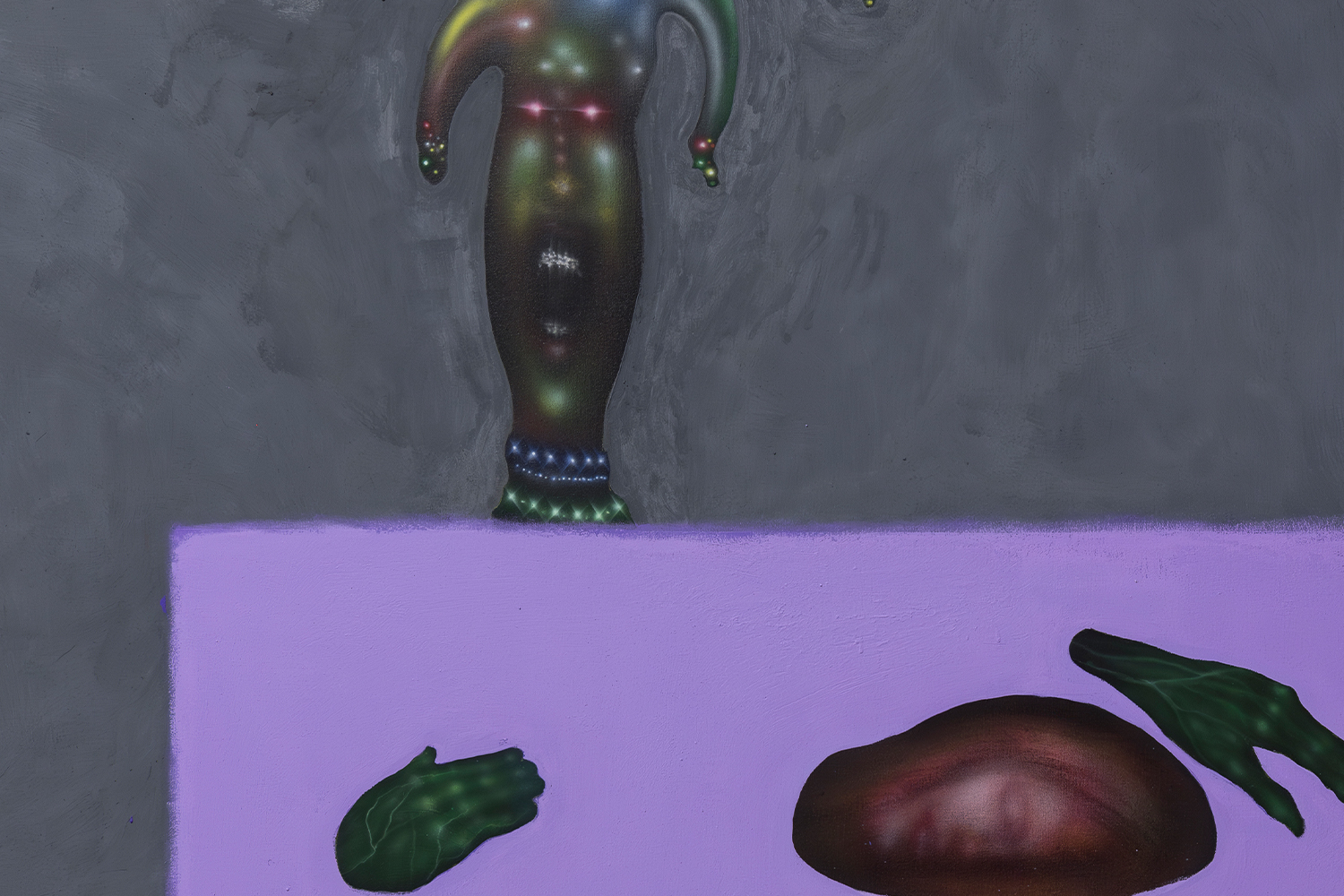

BB: Your newer works, Ultimate Vatos and Xenon Palace — the piece you showed recently at Basement Roma — explore themes of loneliness and singularity: a reckoning for the protagonist, Zetrei, and his attempt to find solace within loneliness. Much of your work is about feeling alien in a societal and cultural capacity, particularly as a Muslim man trying to navigate a Western world. Can you tell me about loneliness within the context of your work?

SS: Every time I’m writing a new character I find myself writing, “He is a lonely man.” [laughs] Before I met Émile I was so lonely, but I really embraced my solitude. It was something that I cherished. Now I share it with Émile-Samory. We are lonely together. The lonely man in my work is always related to my little brother who lost everyone and everything. It’s not all he is, but he is a lonely Muslim, Maghrebi man. I think that, subconsciously, all the stories that I write are for him. A story where he, as a lonely man, is the hero. Muslim men from the diaspora, immigrants, are lonely men. Even amongst their community

they can feel lonely. In my art I want to embrace being a Muslim: it can go unsaid, but in all of my scripts there is a mention of Allah or believing in God or In sha’Allah. It’s so important in France to celebrate it, but we don’t need to showcase being Muslim. We are Muslim. I don’t want to hide my reality just to please people. Islam is taboo in France — for some people being a Muslim is being a terrorist. If I really wanted to be a super-popular artist and I wanted everyone to love my work, I would hide it, but I don’t want that.

BB: My father came to see “Real Corporeal” at Gladstone Gallery and he watched your piece Ultimate Vatos from start to finish. He asked me, “Is it about Muslim extremism? Is it about terrorism?” I asked him why that was his interpretation and he said, “Well, the man seemed very angry. He spoke about how Muslims are treated like rats.” Does the fact that a Muslim man is angry about the way they’re treated by society mean they’re extremists in their views? For me, no, but it was saddening and eye-opening that my own father would think that. I know his views represent those of countless others. I was able to open a dialogue with my own father because of that film. There’s so much power in that… Sorry, it’s making me emotional!

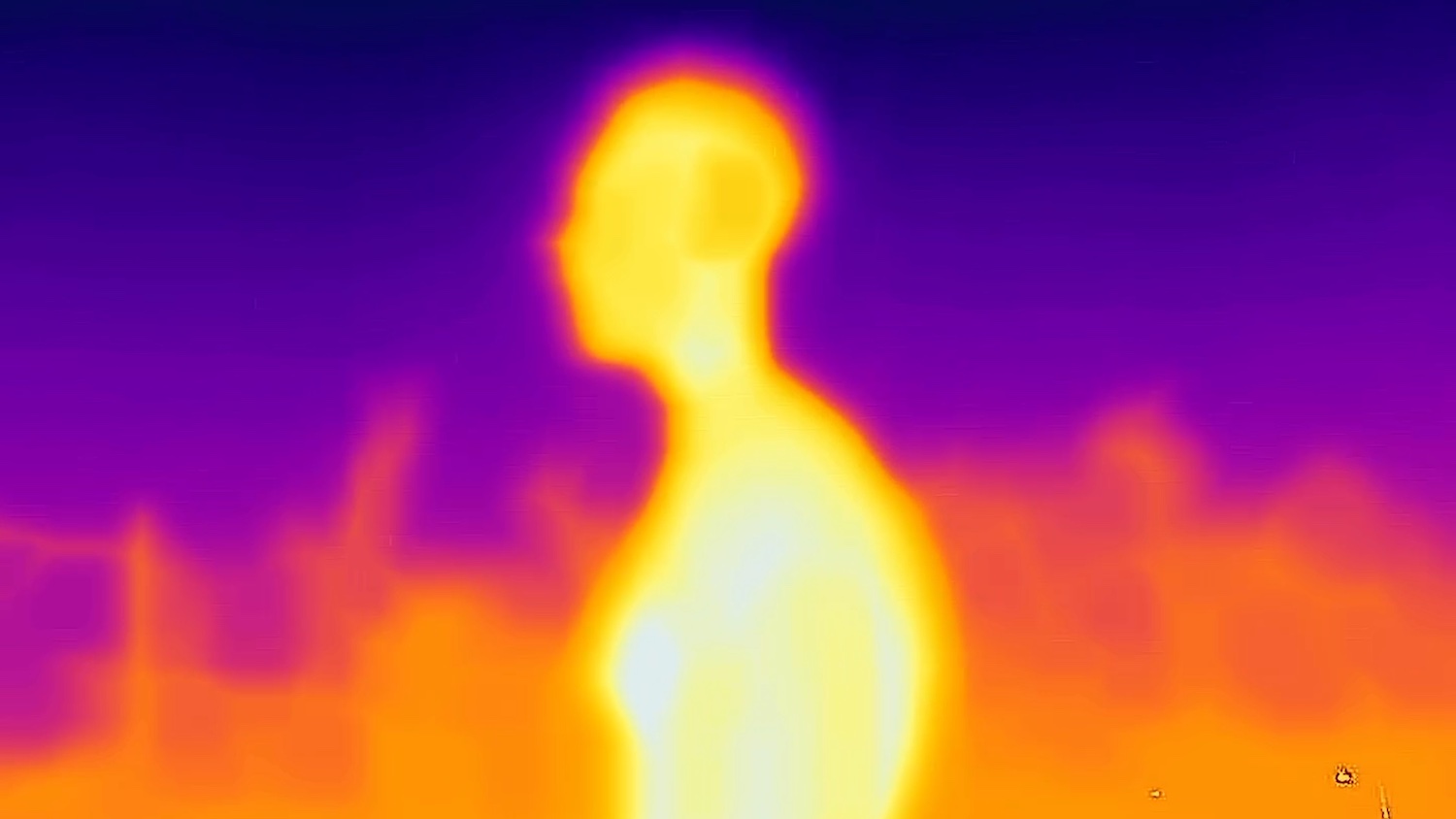

SS: Yeah, me too! So many people can’t conceive that a Muslim man can feel anger without wanting to blow us up. But no, he is just angry because of everything he suffers. Ultimate Vatos is inspired by Émile-Samory’s life and challenges as a black Muslim man. The direction and writing are informed by his own genuine, real-world experiences. His character embodies both violence and tenderness. The way this is interpreted depends on the person watching the film. There are some phrases in the monologue, three or four sentences, that are slogans from French army advertisements. Messages like: “I’m protecting my country because I’m progressing my life” or “I want to be the new breath after the storm.” When inserted into my work these phrases resonate differently. I knew that if I used these sentences in another context they’d be perceived differently by the audience.

BB: In much of the Western world Muslim men don’t have an opportunity to feel like individuals; their personhood and personalities are homogenized. One thing you do so well in your work is to give back this personhood to your characters. Your films are all about the individual. They’re about a unique experience, which speaks to the experiences of so many others. Do you think this focus is important?

SS: When I write a character I try to delve deep into their personality. What are their dreams? Who are they as a person? French society only speaks about the group, “the Muslims,” never who you are just as yourself. It’s important for me to create different characters across different works but to always focus on the individual. In twenty years I want to have many different characters. They are always Muslim men, but they don’t have the same life. The differences between characters is important for me.

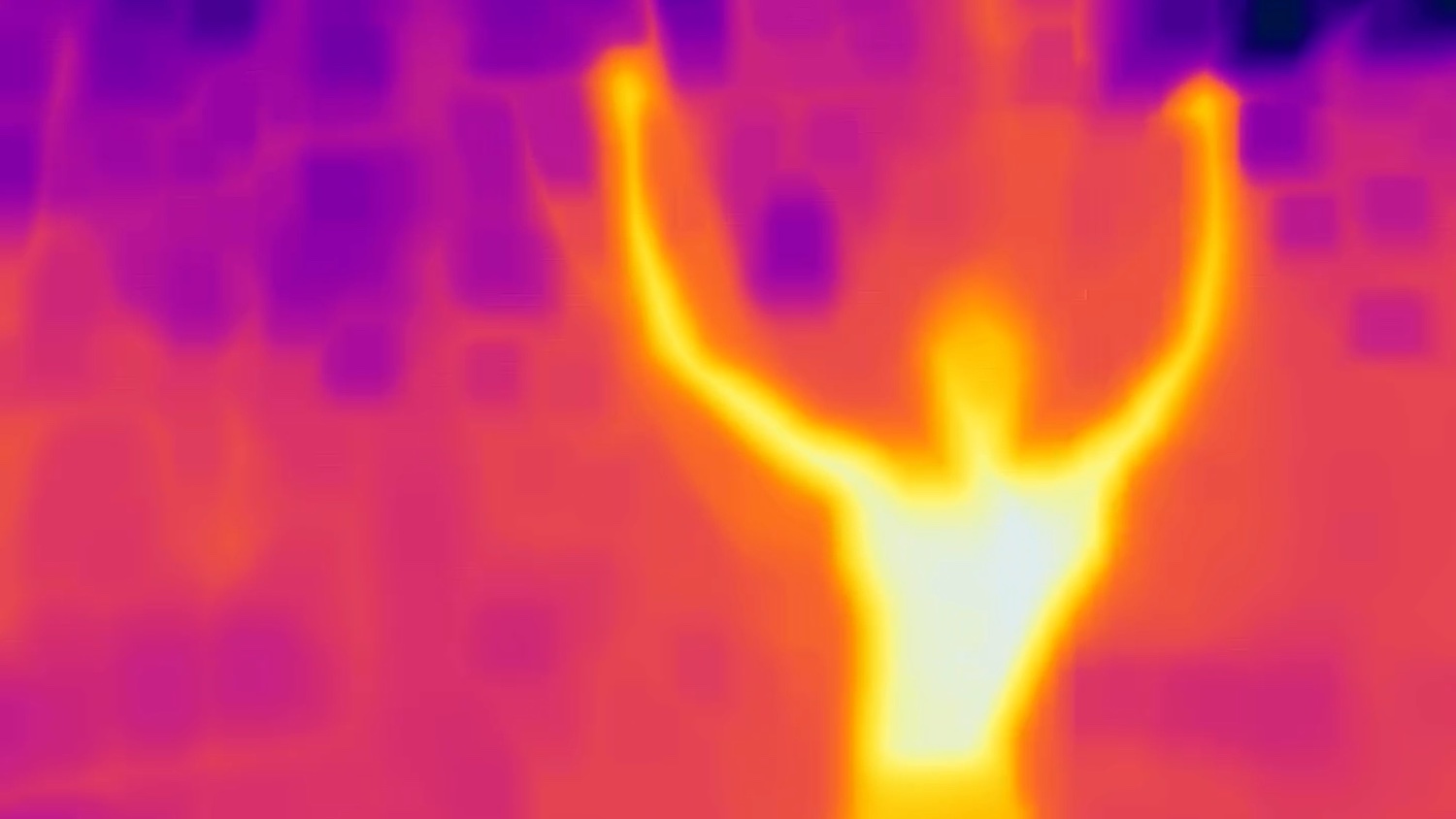

BB: Whilst your work may focus on the individual, you yourself do a lot of work to uplift your community. People from the Maghrebian diaspora might not see themselves represented in art spaces, they may not have artists to look up to. Do you feel a responsibility to be that artist?

SS: At first I felt a weight on my shoulders. When I was in art school I didn’t have any artists to look up to. I had no role models. In my third year I discovered the work of Mohamed Bourouissa and Meriem Bennani. We have some cultural meeting points and I could relate to their work, but they’re older than me — they’re from another generation with different reference points. I started exhibiting whilst I was still in art school, and in France it’s really rare to have a foot in the art world at this age. I was a bit precocious! I was so stressed. People were looking up to me and I didn’t want to mess anything up. If I did something bad it was bad for the community. I never bragged about my successes but I did feel pressure. Now there are many artists around me at the same level, so the pressure went away and I feel more free.

BB: What was your entry point? Was there a catalyst that sparked your interest in art?

SS: I come from a small city near Bordeaux named Floirac. Most of its residents are from low socioeconomic backgrounds. I’d never been to the museum, never seen an exhibition. I didn’t know what art was. And then I went to a high school for rich people — I chose this school only because it was in Bordeaux. I just wanted to move from my little city and come to the city center. My very first entry point was through a graphic design class. But I didn’t like it. I didn’t feel a connection. I just wanted to get my diploma. Then, later, studying at Beaux-Arts… still no feelings. I remember I typed into google “contemporary art banlieue.” I wanted to know if it existed. I found the work of Mohamed Bourouissa and I thought, “What the fuck! It does exist!” It could have been my father in those photographs — not my father in Morocco wearing a traditional outfit, but my father in my own neighborhood. Something switched in me. I realized it was possible to make art telling my own story without having to invent a new life. From that point onwards I was producing so much: working all day, writing video, shooting video. Seeing Bourouissa’s work made me realize, “Okay, it’s legitimate for me to make art.”

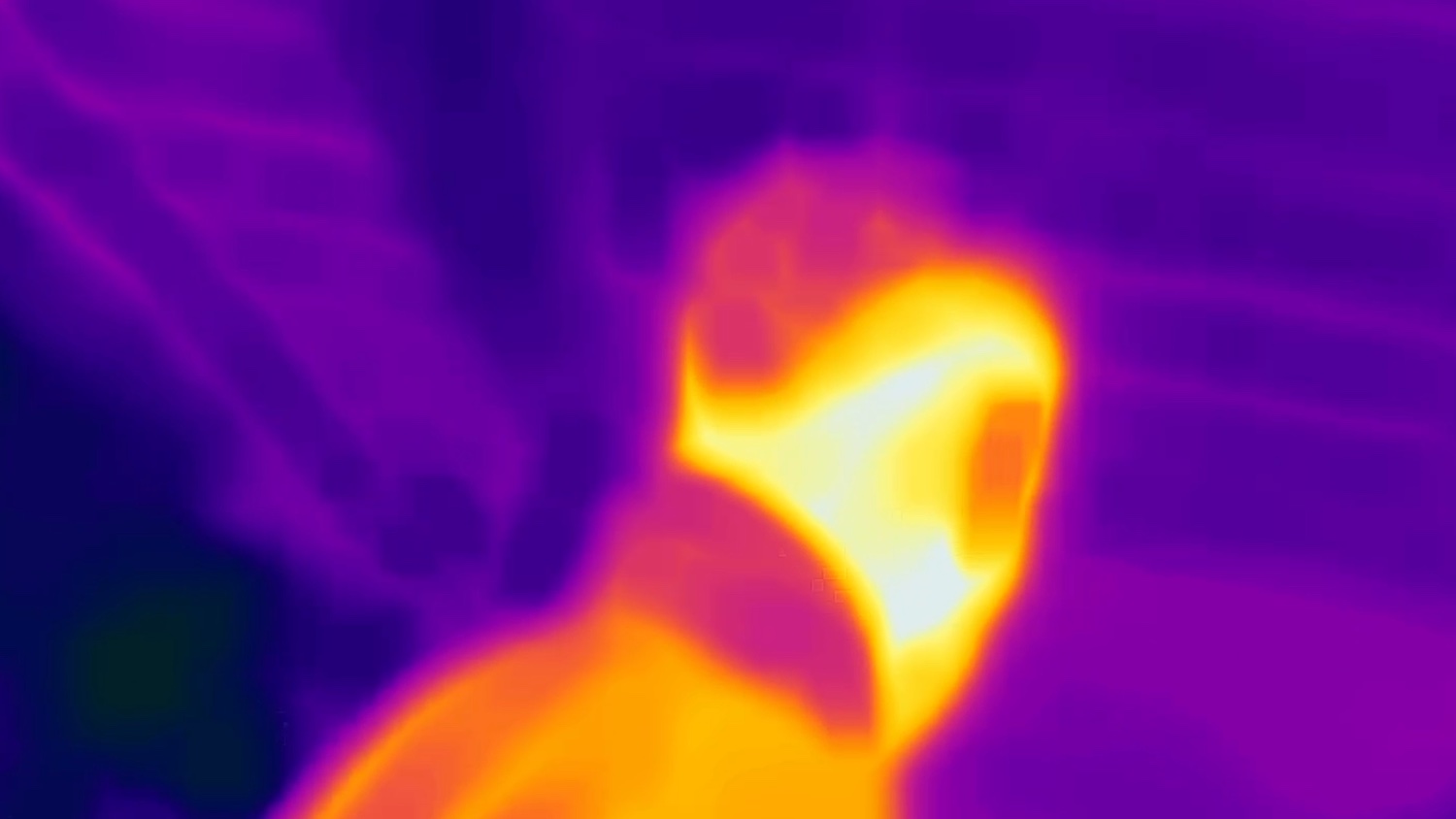

BB: Video can be one of the most accessible art forms in that everyone has a video camera in their pocket and anyone can learn to edit online. Did you initially choose video because of that accessibility?

SS: I chose video because I didn’t know how to paint! It’s not like my father had a video camera or my mother did some painting. When you don’t have access to art and you don’t know how to create something with your hands, it’s not easy to realize you want to be an artist. In school we were looking at the work of Ryan Trecartin, and it struck me. I didn’t have any other references, so I thought, “I want to do the same.” I rented a camera, started using a green screen and shooting myself. That was the beginning. I was watching a lot of YouTube tutorials on how to use the camera, how to edit, and how to do lighting. I was so bad at lighting that I was scared to shoot outside, so it was always in front of the green screen. I fell in love with this process.

BB: People often attempt to explain your work through its closeness to French rap — both the music and its aesthetic. An art-educated and largely white audience might listen to a PNL song and think they can get on board with Sara Sadik because they have this frame of reference. I know rap is a big influence for you, but can it also be damaging to attempt to understand your work only within this context?

SS: For some people the only frame of reference they have to understand me is French rap. Maybe I’m naive, but I’m glad for the association. French rappers were the first artists that I met in my life. For me, the rapper JuL is the best contemporary artist. How they write their songs is similar to how I write my films. The visual aesthetic of French rap videos is more than a reference for me — it’s the essence of my work. My work was born from rap and, creatively, rap was the only thing I had when I started out. If people can relate to my work through French rap, I’m happy.

BB: So whilst your audience may not fully understand your cultural reference points, the fact that they’re still engaging in your work is a good thing?

SS: Up until my last project I was trying to say something by taking a political stance or having an overarching message. I’m a Maghrebian woman in an art world with all these old white men. I wanted to show them. I wanted to tell them. I wanted to not have to explain. Now I’m thinking less about a message and more about storytelling. I know the audience. I know who is going to see my work. I was thinking of them — not wanting to please them or create something for them but knowing I will provoke them. I know my work can anger people, and a part of me enjoys that. I don’t want to get lost thinking about who is going to see my work. I don’t want to fall into that hole.

BB: So when you create now, who are you creating for?

SS: It’s for people I love, people that feel connected to my stories, for my brother and for me. Xenon Palace is a work that’s so close to me. It’s my own story, mine and my brother’s. My work is the same, the subjects are the same, and the messages are the same. But the way those messages are portrayed are changing. In my previous works the messaging was really direct, but now I don’t think about being straightforward. I just want to tell my story.