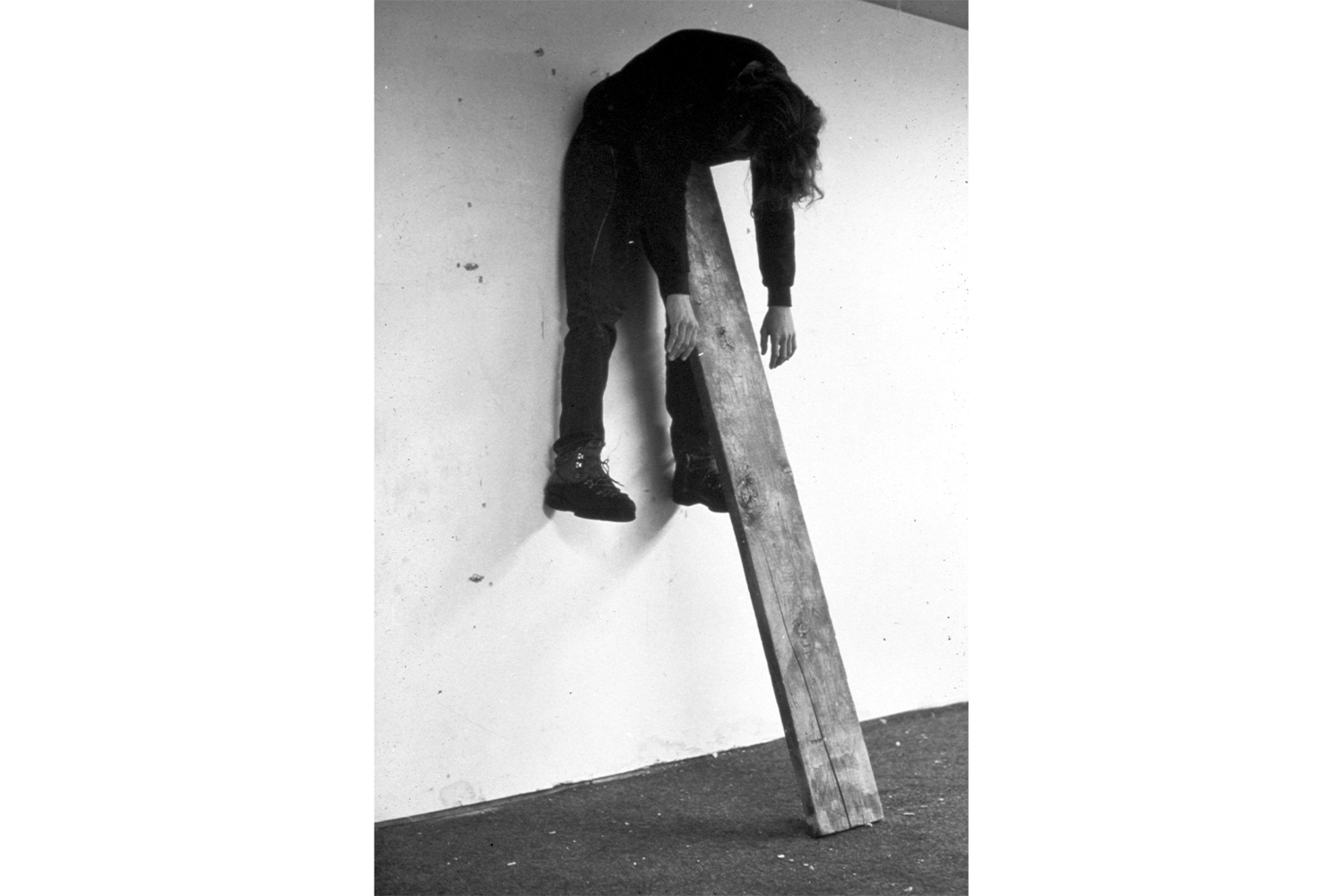

Plank Piece I and II (1973), a black-and-white photographic diptych showing the young Charles Ray’s body pinned against the wall by a wooden plank, along with All My Clothes (1973), a series of sixteen photographs showing the artist dressed successively in the various outfits in his wardrobe, from thickest to thinnest, in a direct reference to Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), mark the genesis of anthropomorphic representation in his work. They also embody the beginnings of his exploration of the very notion of sculpture, in the expanded sense, and bear the trace of his post- Minimalist work from before 1984, which has been entirely destroyed. These two key works hang in the Centre Pompidou, which is presenting a double exhibition, in conjunction with the Bourse de Commerce, devoted to Ray’s figurative corpus, comprising some hundred works, bringing together more than a third of them, all later than 1985.

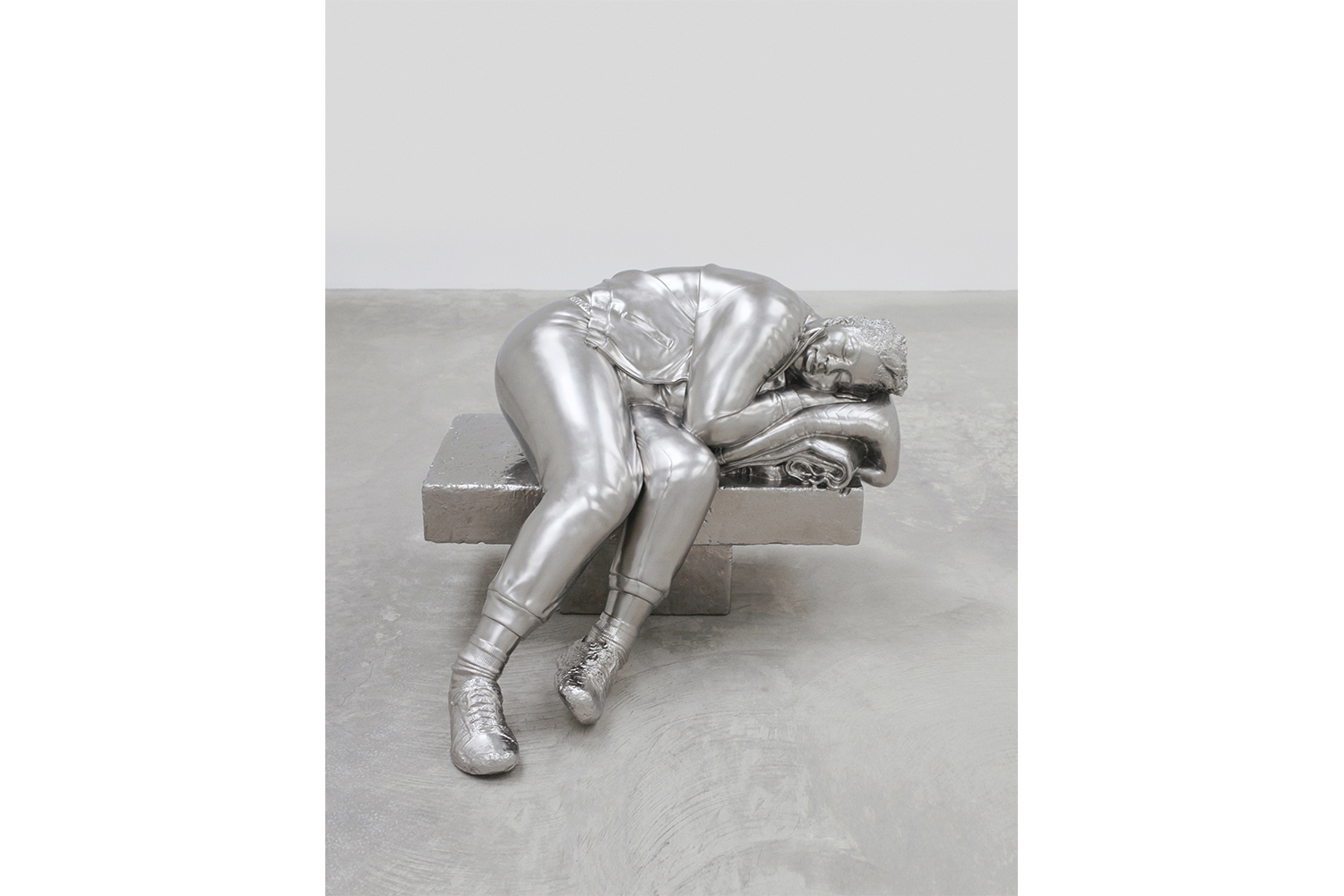

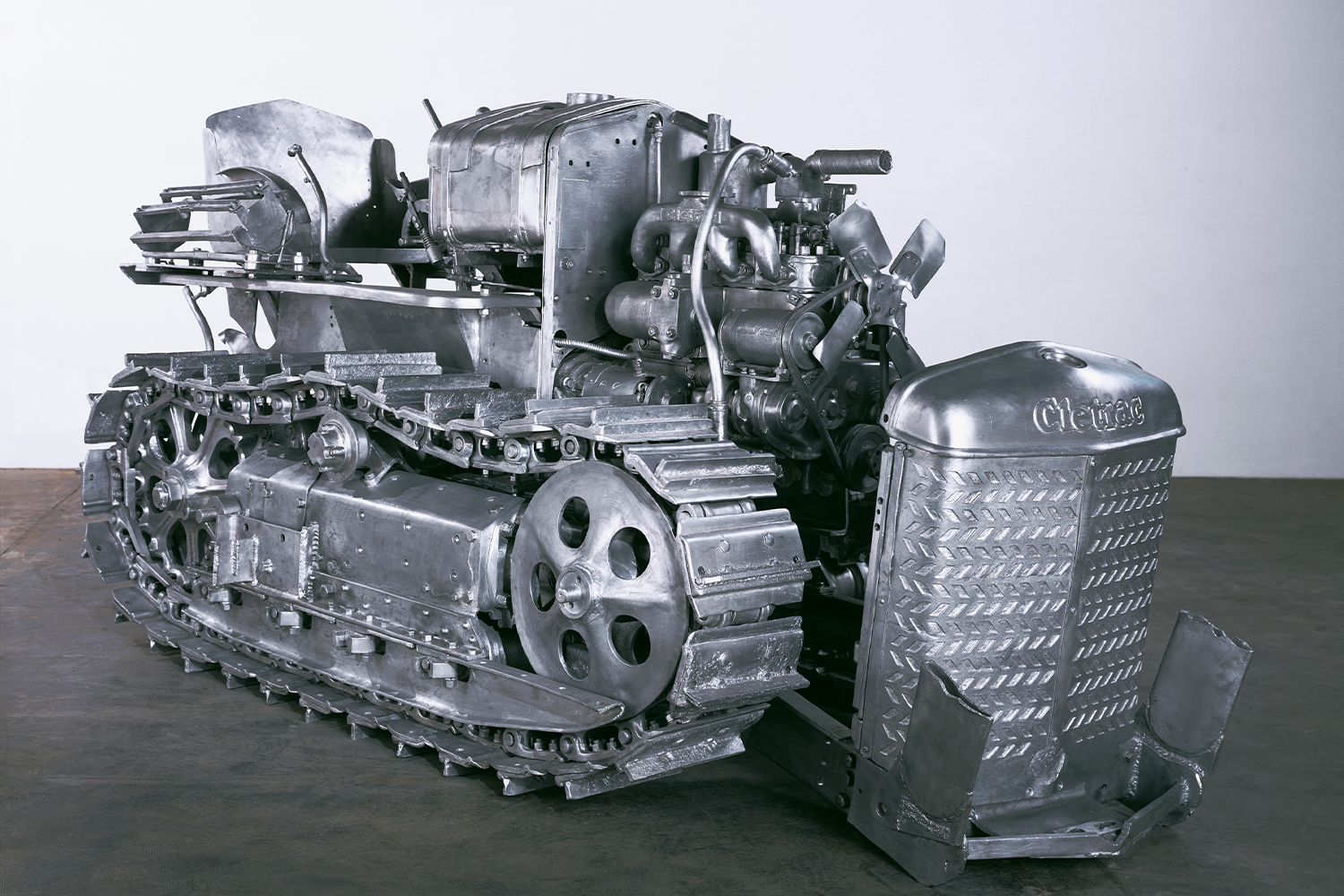

The most recent works are being shown at the Bourse de Commerce, which offers a far-reaching view of the underside of the American dream through seventeen works, seven of which are later than 2019. Horse and Rider (2014), an equestrian statue without a pedestal, sculpted entirely by machines in shiny blocks of stainless steel, with a hunched Charles Ray as the disenchanted rider, opens the exhibition at the Pinault Collection, foreshadowing the formal appearance of the works displayed there, almost all of which are structured around the contrast between a shiny visual perfection, possibly representing the glittering attractions of the American dream, and a critical vision of the reality of the latter, expressed in the objects and models represented and in the emphasis placed on the ephemeral nature of everything. The automotive objects of desire, emblems of American progress, such as Unbaled Truck (2021) or Tractor (2005), are vehicles destroyed by time and abandoned, which Ray has collected and painstakingly reconstructed in other materials. The characters, such as Sleeping Woman (2012), a shiny sculpture of a black woman on a bench in a deep, massive slumber, Burger (2020), a careworn man eating a hamburger, and Girl on Pony (2015), a gleaming bas-relief of a pre-adolescent girl on horseback, deconstruct the myth of the American way of life in meticulous and strangely vacuous figurative portraits. Most of them depict the finiteness of the human condition, either implicitly or more explicitly by bringing together pieces representing different stages of life, in works like Return to the One (2020), Doubting Thomas (2021), or Boy with Frog (2009). The formal perfection of the works, their purely descriptive aspect, evokes the modalities by which Georges Perec, in Les Choses (1965), describes the objects of desire of a consumer society avid for appearances, allowing us, perhaps, to understand the extent to which everything in Ray’s work is conceptual.

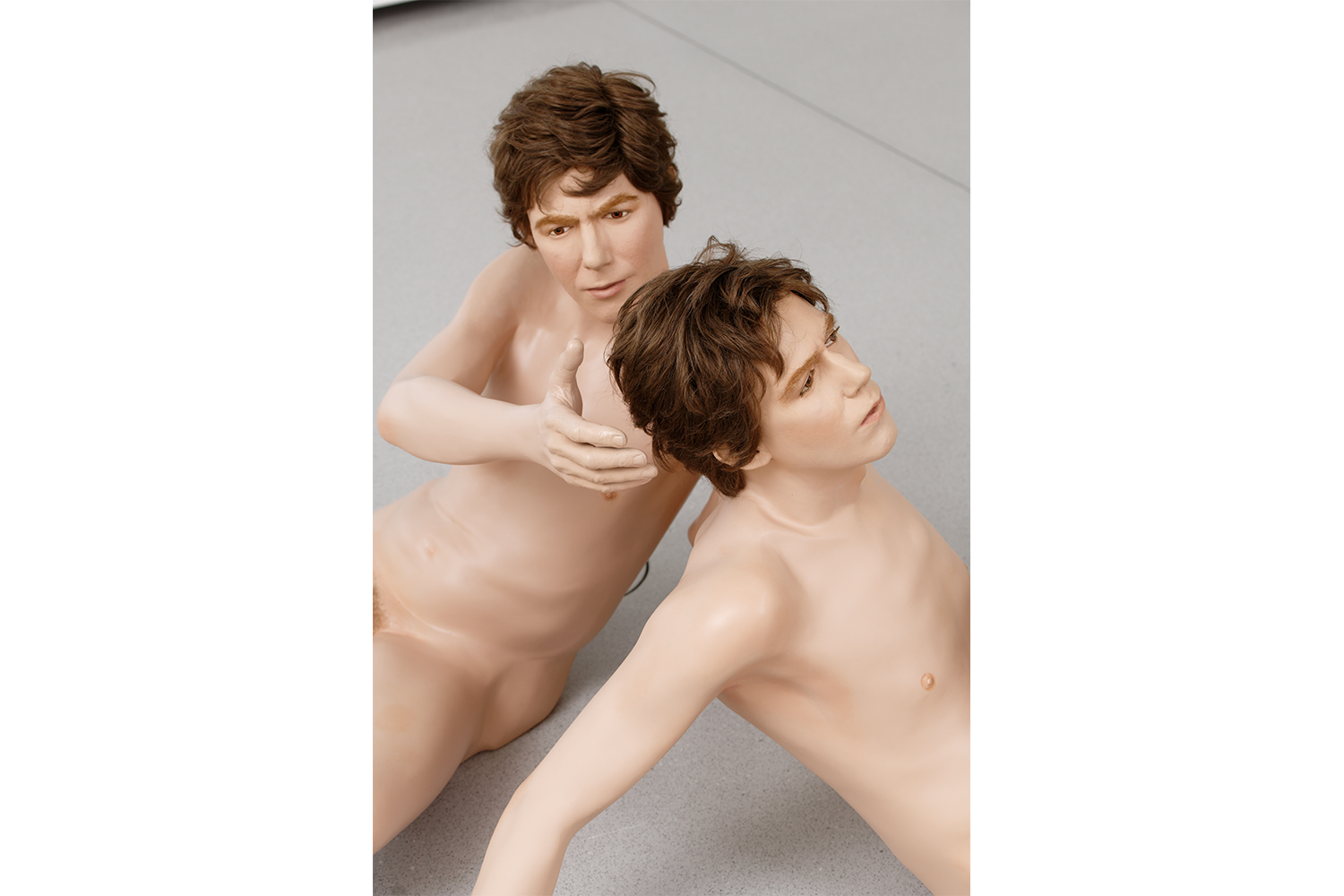

Both exhibitions are articulated around Fall ’91 (1992), the sculpture of a shop window dummy dressed in the 1991 fashion, whose height of 2.44 m (8 feet) constitutes a more obviously pop foretaste of the later monumentality of Ray’s statuary. At the Bourse de Commerce it follows Oh Charley, Charley, Charley (1992), a sculpture of an orgy in which all the characters are effigies of Charles Ray.

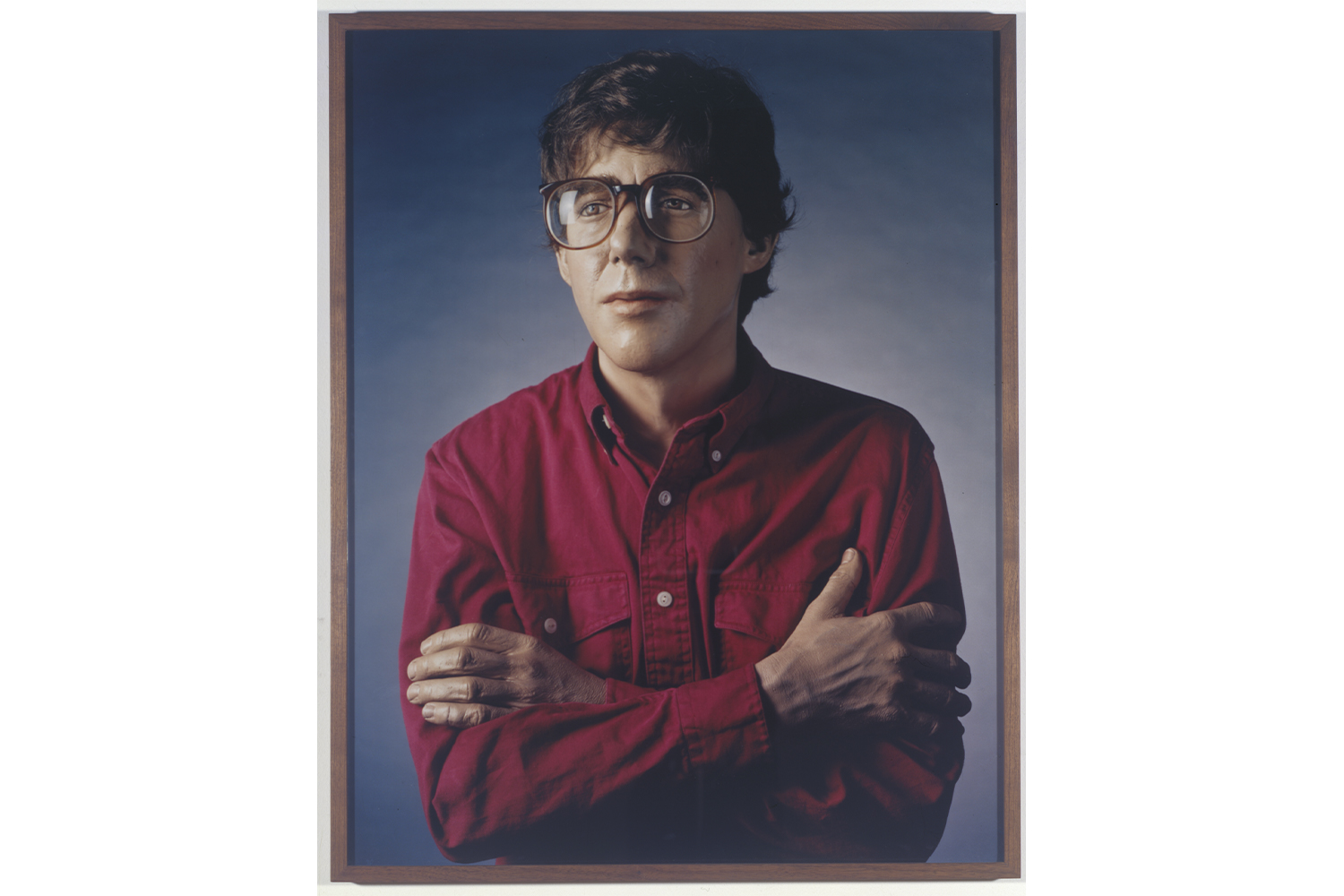

At the Centre Pompidou, where the show is structured around a historical perspective and traces a fascinating unwritten genesis of the works through twenty-one of them, a version of Fall ’91 dressed in red is placed side by side with the set of sixteen photographs that make up All My Clothes (1973), suggesting a post-Minimalist as much as a Pop origin. Triangulating it with Self Portrait (1990), a simple modified mannequin whose face is designed with Ray’s features and which wears his clothes — Ray’s first work to explore sculptures of mannequins — and with Yes (1990) and No (1992), two large-scale photographic self-portraits, one of which is hung in a concave frame on a wall which is itself concave, and the other a photograph of a dummy in the image of the artist, completes the process of tracing origins and exploring the complex relationships that Ray establishes between photography and sculpture in his work, suggesting that both can be conceptual in essence.

The pop dimension of Fall ’91 — and beyond this, of Ray’s work as a whole — is humorously underlined by its proximity to Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (2021), a provocative piece of pure pop covered with 1970s colored floral motifs, referring us to the chilling significance of the sculptural group Family Romance (1993), a set of four dummies representing parents and their two children, holding hands, entirely naked and all the same height, 1.35 m (4 feet, 5 inches). As an echo, How a Table Works (1986), a table structure traversed by a lighter steel construction which keeps the objects of a still life as if in levitation, a purely autobiographical work of the artist, depicts the place where the family gets together for meals and evokes Ray’s loss of his brother, which occurred in 1984 and had a major impact on his oeuvre. It concludes the exhibition, as a counterpart of Plank Piece I and II, and marks the transition of Ray’s conceptual/performative output to his figurative sculptural work, while also finding its antidote in several works homothetic with those shown at the Bourse de Commerce, as well as in Hinoki (2007), a gigantic dead tree trunk reproduced in Japanese cypress, characterizing an explicit resistance of a philosophical nature to urgency and ephemerality and the very notion of consumption.