In a small vestibule painted library green (Benjamin Moore 699), personal artifacts from Barbara T. Smith’s archive, acquired by the Getty in 2014, are on display within an arrangement of museological vitrines. That her marriage album is on display is telling: Smith’s major survey at the Getty Center celebrates fifty years of the artist’s career, folding autobiography into the exhibition.

“Welcome,” Smith writes. “This exhibition […] is all narrated by me, Barbara.” Many of the gallery’s first-person wall texts are excerpts from Smith’s memoir, recently published by the Getty. Born in 1931 in Pasadena, Smith lived “a charmed life.” She was happily married with three children, a home in the suburbs and a beach house in Laguna, when her resolve in the narrative arc of her life began to waver. “I do what is expected of me,” she writes retrospectively of this period.“But soon I will wonder what it all means.” “BarbaraT.Smith: The Way to Be” chronicles the artist’s spiritual, sexual, and psychic transformation from housewife and mother to transgressive artist. Contrary to most gallery exhibitions in which a curatorial vision precedes its attendant publication, “The Way to Be” retrofits the display to accompany Smith’s memoir, gliding from archival document to artwork. The Getty attempts a distinction by replacing the muted green-gray walls at the entry — a nod to the Arts and Crafts era and Smith’s classical upbringing — with stark white ones as Smith’s own work comes into view.

Smith’s liberation began at home. In 1966, she leased a commercial Xerox 914 copier and had the hulking machine delivered to her family dining room. Instead of hosting dinner guests, Smith sat down with her copier and got to work making prints. She used her body, her children, anything she could get her hands on to make haunting, layered images that eventually became books. She referred to the books as “coffins” (Smith descends from a family of esteemed Pasadena funeral directors). In as much as they represent an ending, the books in this series articulate, in an emerging visual language informed by the 914’s internal processes, Smith’s recognition of searing female desire and its dreadful incompatibility with her domestic life.

FYI: I dread driving to the Getty. I dread riding the tram with its orchestral score blasting over the loudspeaker. But I have come because I want to know about the housewife who in 1966 had an industrial copy machine delivered to her home to make a print of a gravestone sandwiched with a flower.

With the copier in place, Smith fantasized about making erotic images with her husband, collapsing their bodies onto a single sheet of paper. She asked him to participate but “unfortunately, he said NO.” After her divorce, art became her everything. Overwhelmed with possibility, Smith began to pursue ambitious sculpture and performances that explored spiritual-sexual enlightenment, centering the artist’s body as a material interface for personal and social transformation. Field Piece (1968–71), an immersive installation of 180 tubular, resin protrusions that stand more than nine feet tall, consumed four years of her life and the majority of her divorce settlement.

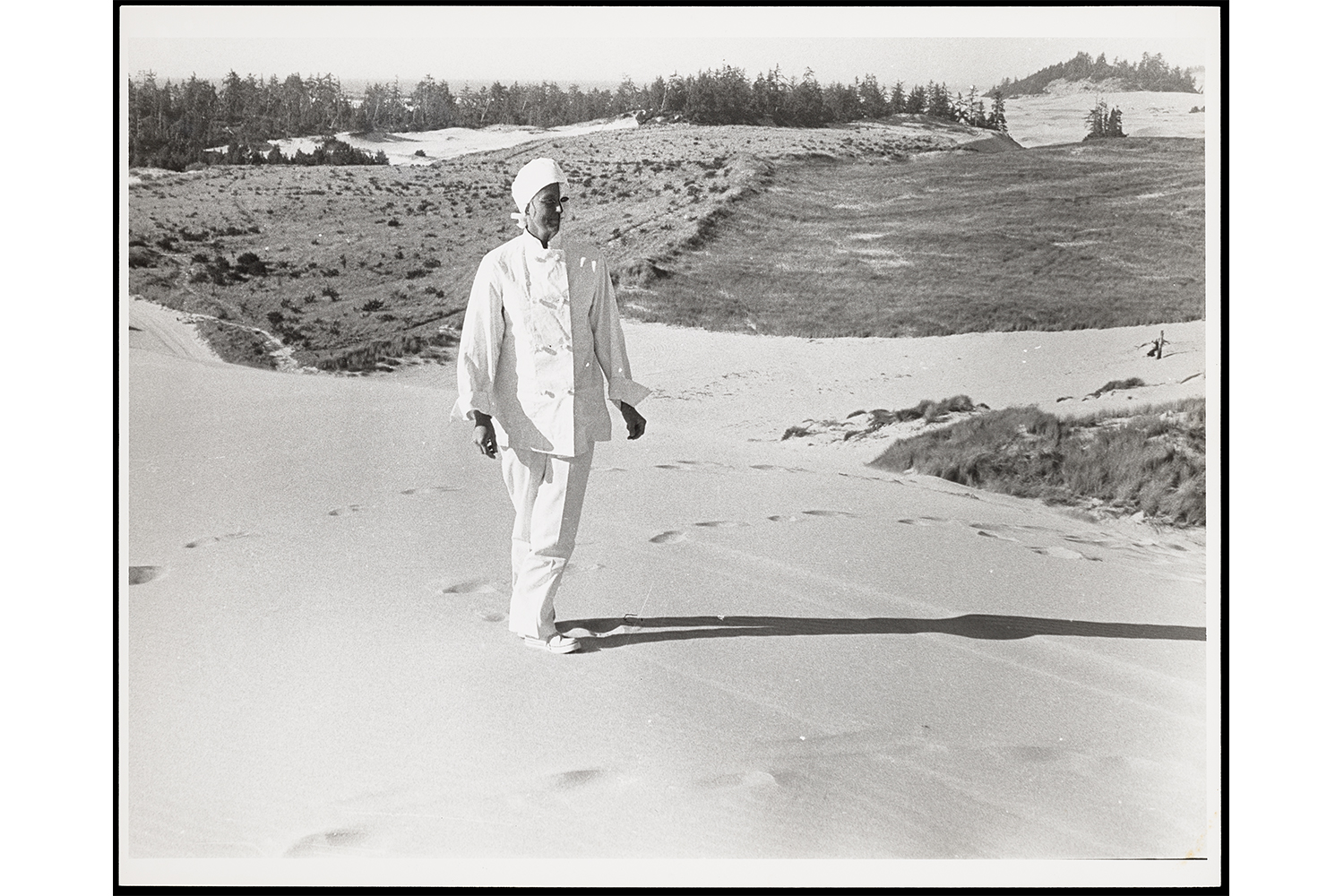

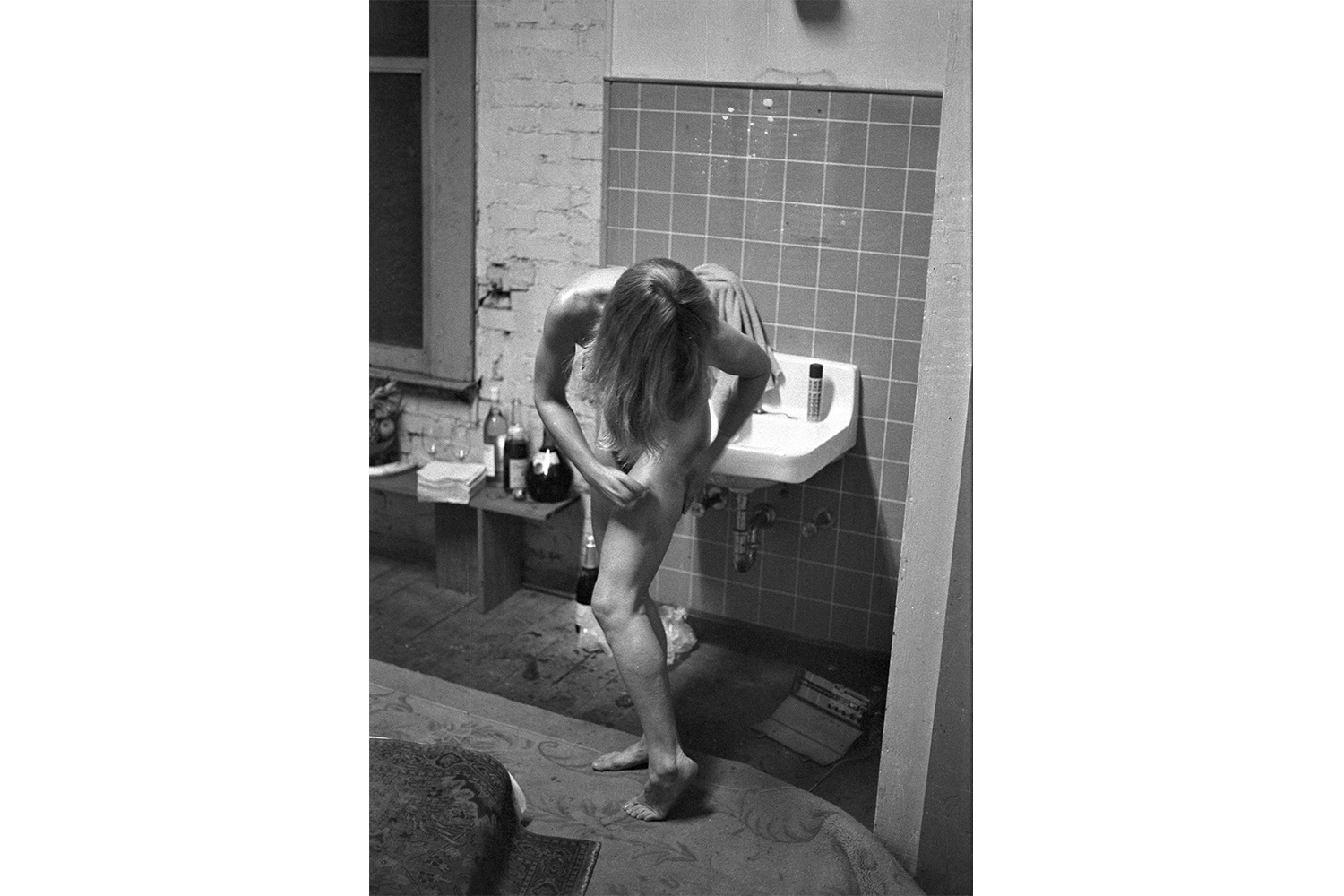

Both independently and with collaborators, Smith staged opportunities to examine practices of embodiment, prioritizing agency as a through line. Though Feed Me (1973) — in which Smith sat naked in a small room inviting participants to provide her with food, wine, tea, sex — was criticized for projecting the feminine stereotype of submission, Smith maintains that consent — giving or withholding — was the work’s empowering feminist under current. It extends an idea from an earlier performance (the exhibition’s titular work), The Way to Be (1972),in which Smith wore white, painted her face, and moved around the world in silence. “I had a sense of presence as I moved, yet I was invisible. Who or what is being, when almost all social modifiers and identification clues have been stripped away?” In this gesture, self-consent is paramount. Smith’s awareness of the violent erasure of her comrades of color and the banishment (or hypervisible objectification) of marginalized bodies remains unclear. Her performances from this time spectacularize deeply personal experiences, prioritizing self-expression. Nevertheless, her work developed alongside West Coast feminist consciousness-raising practices and the feminist movement (Feed Me transpired between Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece of 1964 and Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 a decade later).

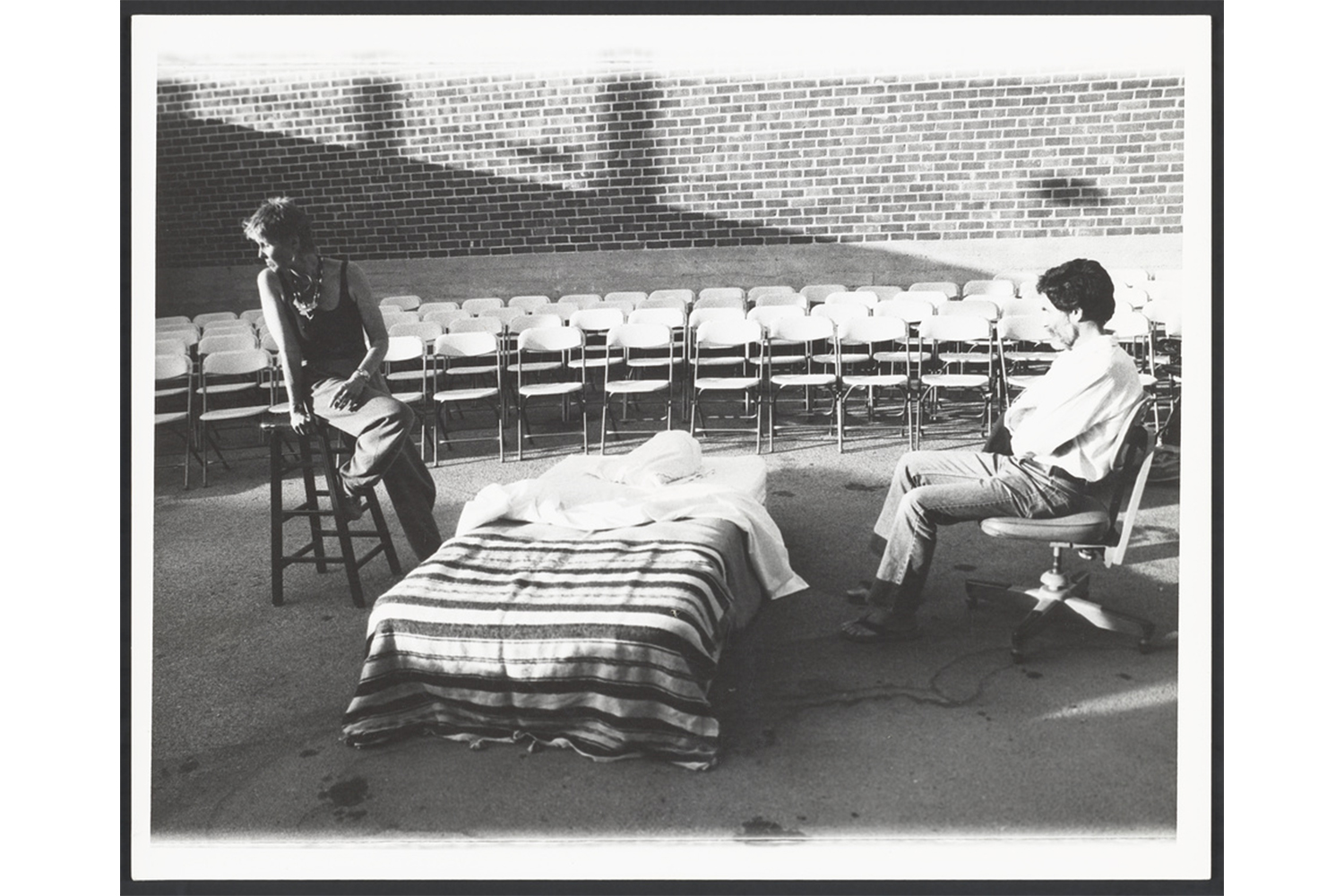

The most recent performance included in the show is Birthdaze (1981), conducted when Smith turned fifty. In text spanning an entire wall, we learn that the piece is structured in three parts that correlate with phases of her life. Grounded in psychoanalytic rhetoric, Smith performs three versions of herself, challenging patriarchal power relations within and across the male avant-garde until the hierarchies are transcended in a tantric act.