One is a critic because one has never felt affirmed (Barbara Kruger never speaks in the third person). There is no other way to be when life has turned out this way, since earnestness disappointed and materiality ignored are tantamount to death. Writing about Kruger has always been, for myself and numerous others, an exercise in shame. Using female artists as the receptacle or hermeneutic of shame is peak Warholian/ Monroeian misogyny. The praxis of misogyny is history, so we say imitatively, “Not 1980s enough.” Eight is Enough. That’s enough! The World is Not Enough. Enough said. At its worst, criticality resigns the critic or artist-as-critic to a moment in time, and time is no longer something that flows. It is instead an immobile stake driven into the heart of something that is or will be dead.

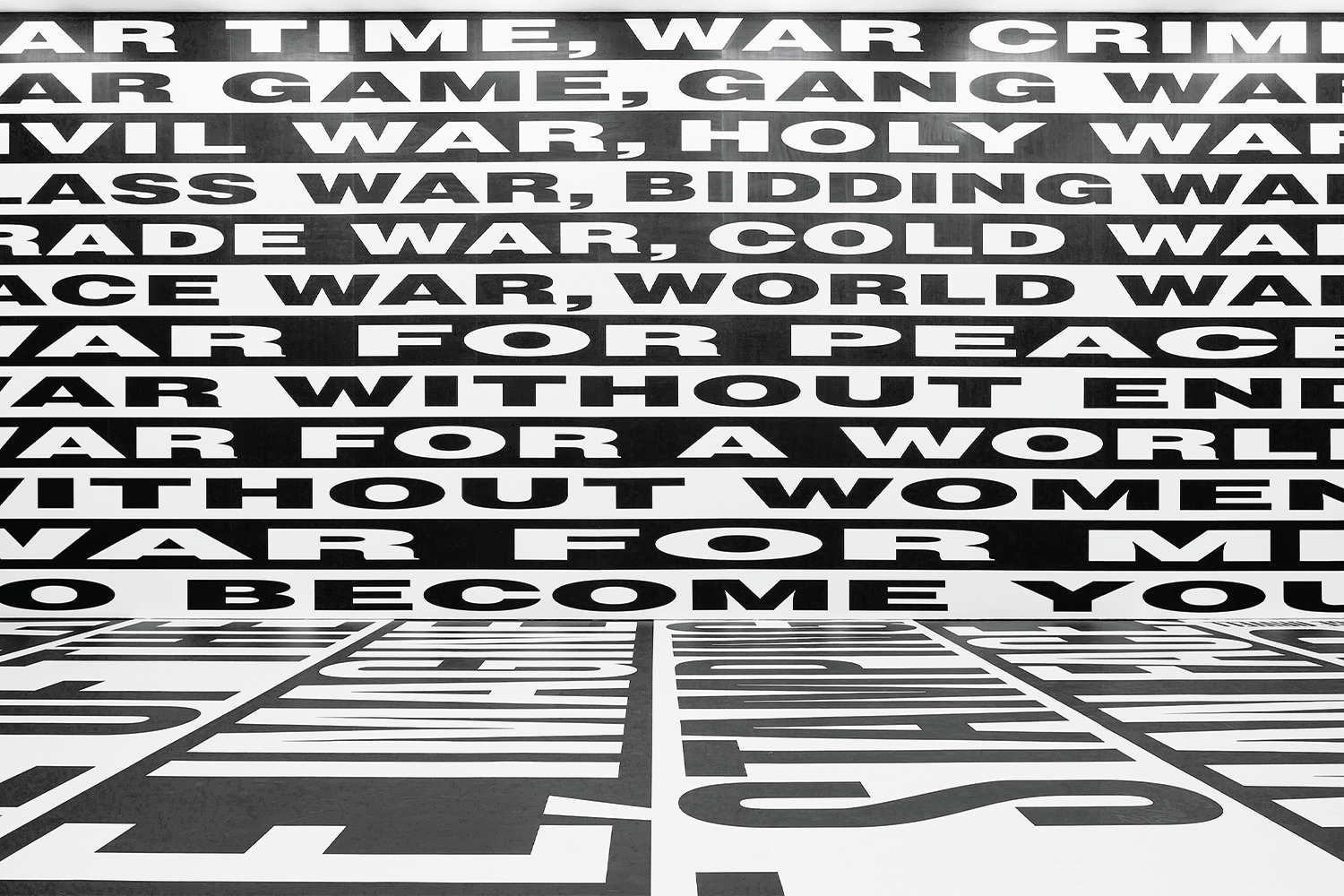

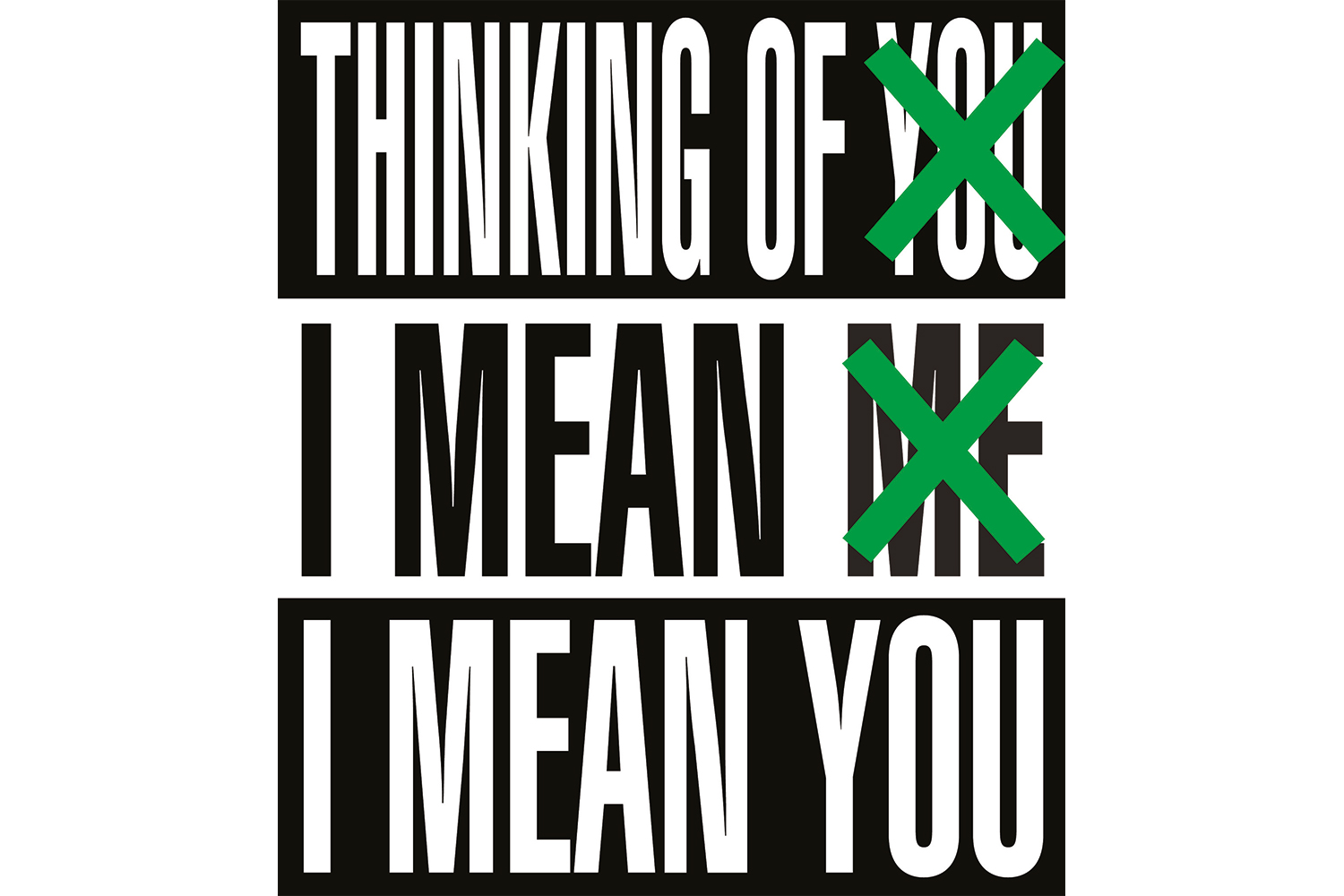

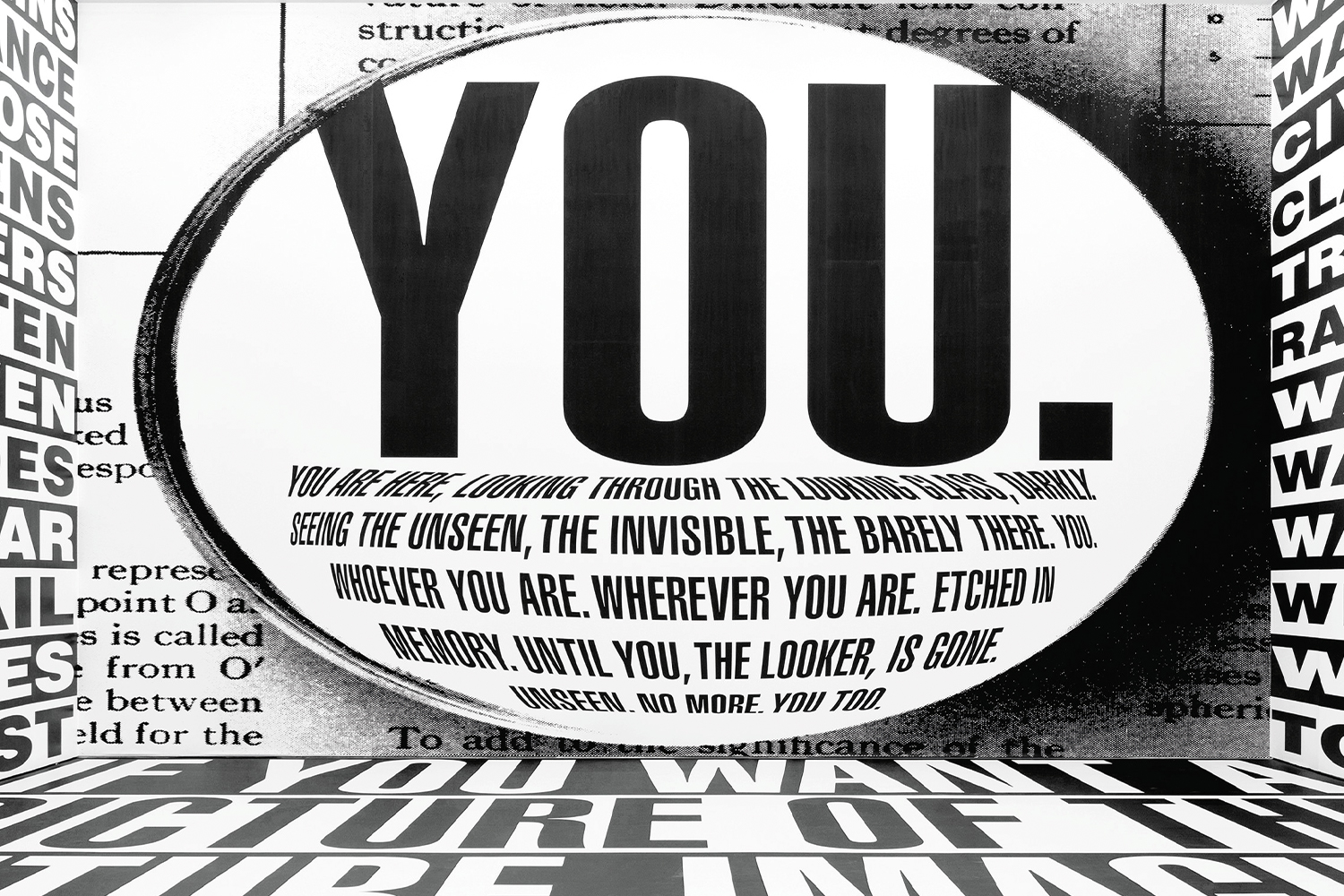

It is unfun and clichéd to ask if there truly can be a retrospective of a queer and/or feminist artist associated with institutional critique. Kruger is both feminist and queer in her work, and she and the organizers of “THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU.” specifically reject the moniker of a retrospective. Kruger has disidentified from periodization altogether. In her essay “Decadism,” Kruger, herself a poet and a writer, argues, “What draws me are the moments between the events: the constancy of the everyday. Of how hours add up to years, of how the vibrantly incremental process of ‘creating’ gels into the inflationary value or abject worthlessness of objects and ideas. It’s the everydayness of street corners, of buildings full of memories, of pleasantly mundane events transformed into ‘historical moments.’” An exhibition, irrespective of its aims to retrospection, therefore is another just instance of poignant drudgery, even if, in the case of “THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU.” that drudgery is, to this fan-critic, fabulous.

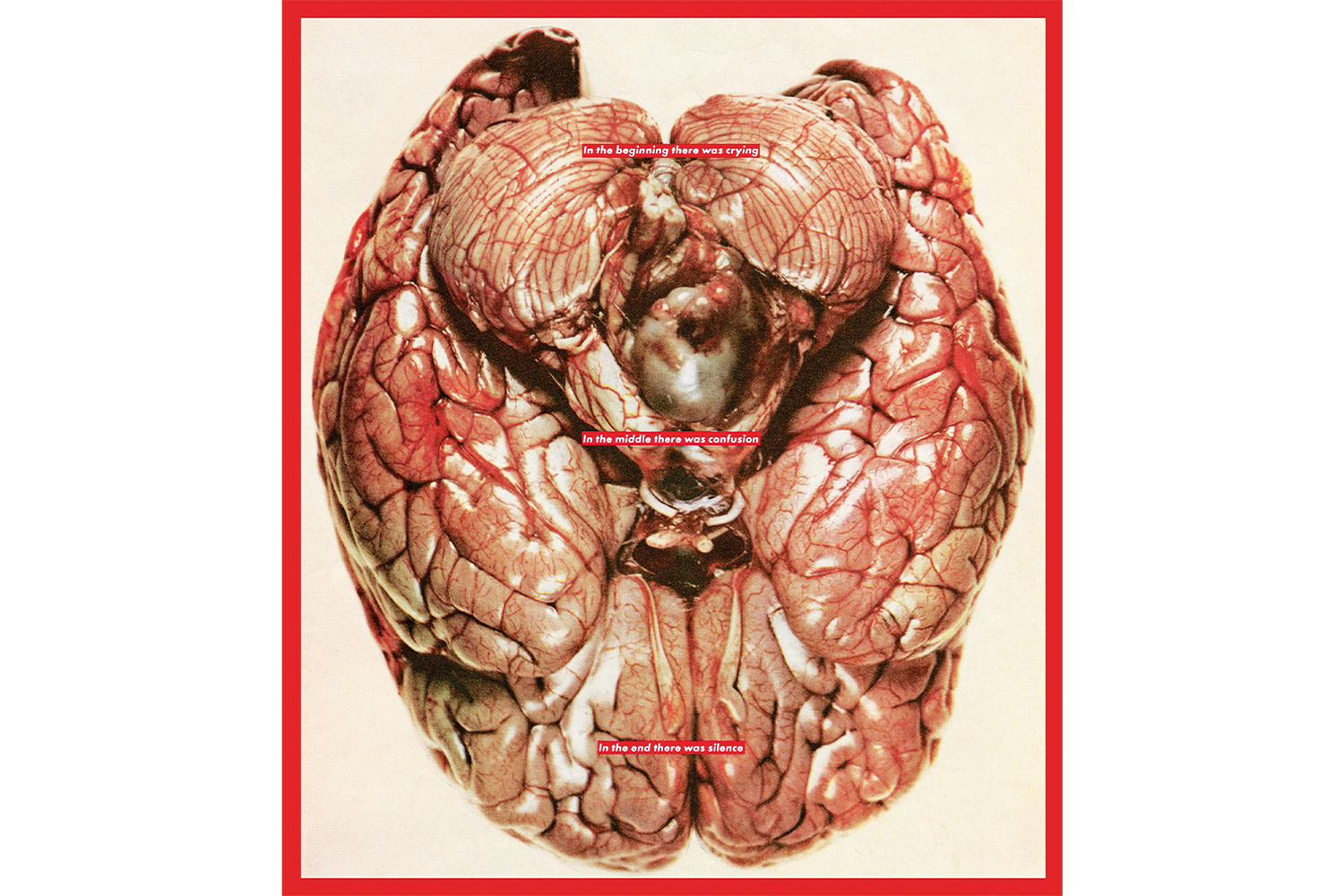

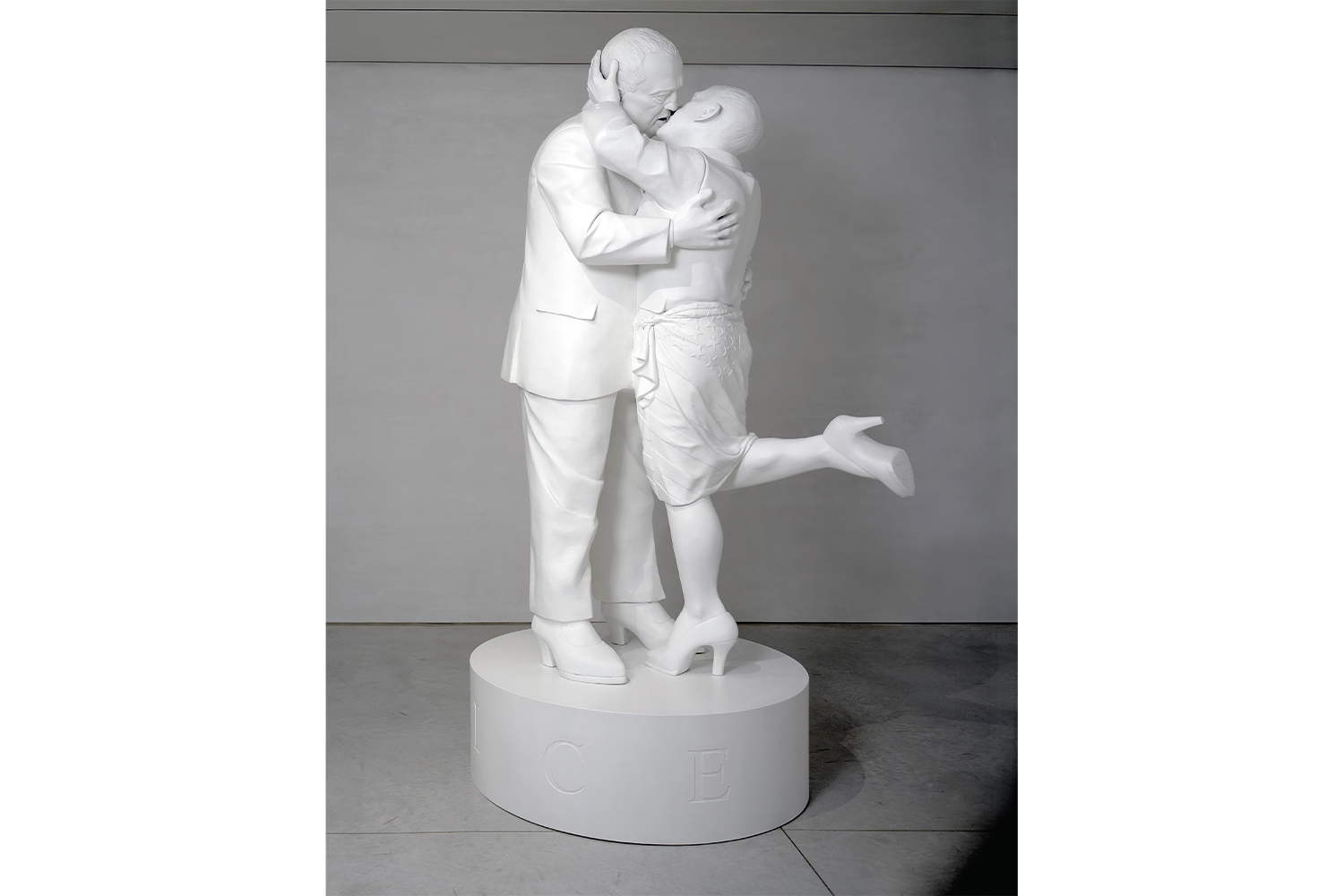

And what could be more constant and everyday, more pleasantly mundane, than a broken heart, a heart broken by stasis and bound by historicization, leaking upon a floor of words left unsaid? History is itself an inattentive lover, the best kind of lover, the only kind. Untitled (Do I Have to Give Up Me to be Loved by You?) (1988) is a melodramatic question that everyone has asked, relieved that the answer is almost always yes. What if we also imagine that Kruger herself, and not an imagined other, asks this of us? For to remain in the 1980s or within the Pictures Generation, to never be allowed to love again, would be for Kruger to give herself up: to the law, to history, to stereotype, to feminist-art-as-bloody-mosquito-caught-in-amber. Imagine if the first person, the first injustice, the first history, the first moment of cringe that broke your heart was the only reason you made art in perpetuity. There is nevertheless always a progression or narrative, irrespective of if we concede that artists or lovers move through it, or if we order them to remain beating hearts underneath the floorboards of a convenient place and time. Kruger’s absorptive brain matter, gray as ash, reminds us: In the beginning there was crying/in the middle there was confusion/in the end there was silence. It is the only universal tragedy, that of motion (tears) become stasis (invisibility).

In the end, there were the ’80s, and in the end, there was so much to be overlooked and perfunctorily rediscovered in a gendered fashion. The text underneath Untitled (Do I Have to Give Up Me to be Loved by You?) (1988) reads: “The vomiting body screams ‘kiss me’ to the shitting body that coos ‘smell me’ to the numb body that mumbles ‘shock me’ to the hungry body that whines ‘I want you inside of me’ to the praying body that whispers ‘save me’ to the dead body that is hard to dispose of.” The heart, the needy organ of femmes and bottoms, is a taught swath of vinyl, skin, asking to be treated like something that can be stepped upon and torn, and not only beheld as a divorced metaphor in a textbook. But then again, even archetypally broken hearts do indeed bleed.