Gea Politi: At Art Basel, Parcours encourages a deeper engagement between the artworks and the urban environment — a different and more “experiential” approach for visitors but also those who live in the city of Basel. Would you say there is a relation between the artworks selected and the surroundings?

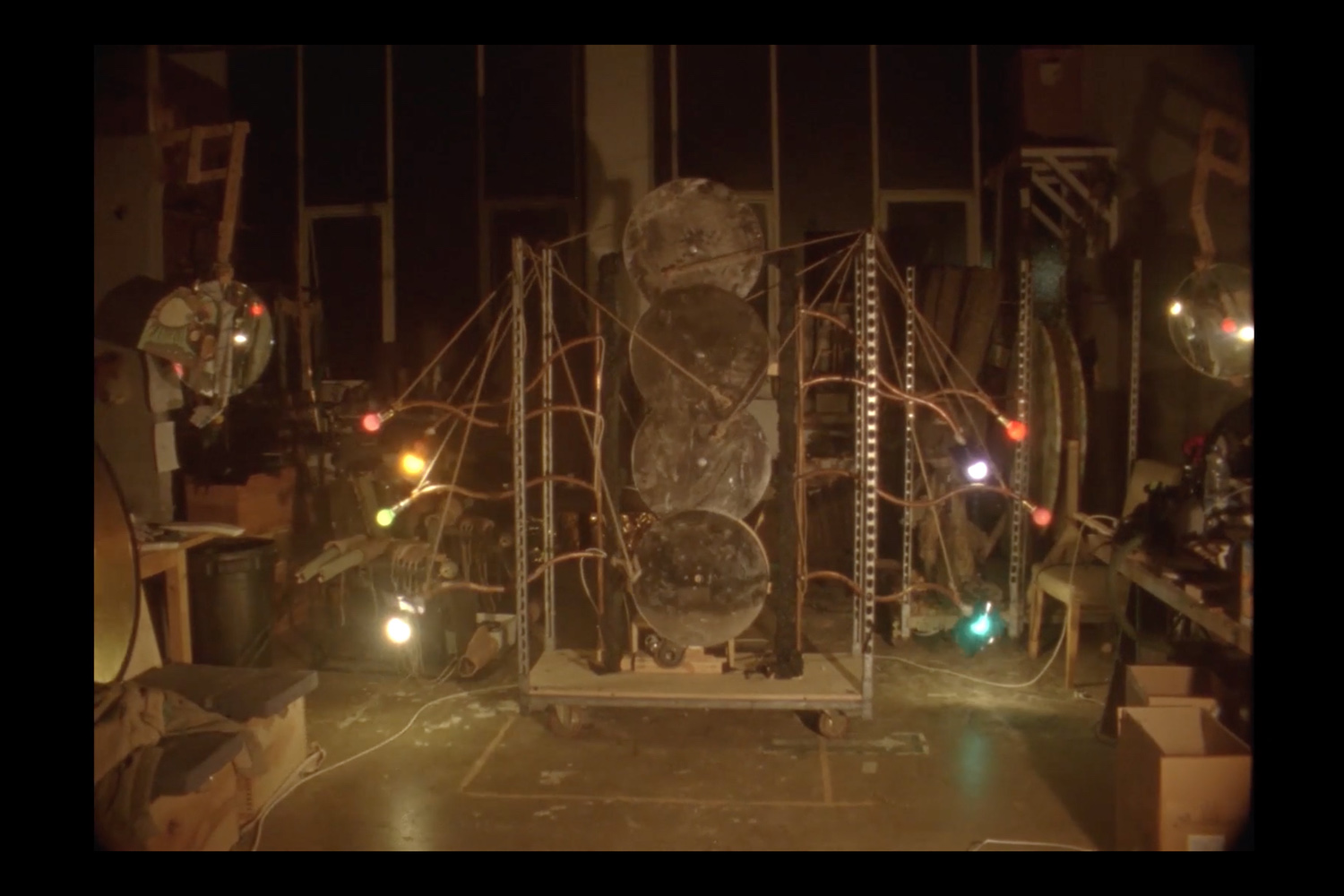

Stefanie Hessler: Parcours is the free public sector of Art Basel. The projects take place in public and private — but publicly accessible — spaces all along and nearby Clarastrasse. The artworks relate very closely to the sites where they are exhibited. For example, Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s installation Conversion systems – vessel V (2019) includes five sculptures that mirror some of the shapes associated with oil distilleries. By using ceramics and steel, the work merges traditional and industrial materials. The artist originally created the sculptures in reference to Lobitos, the petroleum-rich town marked by extraction in Peru. At Parcours, we are showing them inside the Stadtbrennerei, an artisanal liquor distillery — the processes used in the distillation of oil and of spirits are very similar. Alvaro Barrington’s installation inside the store Tropical Zone, which imports African products to Switzerland, was created specifically for Parcours. The artist built a structure inspired by the home of his grandmother in Grenada. On the outside, the structure is clad with corrugated steel sheets and paintings of flowers found in the Caribbean. Inside, products that are usually for sale at the shop are on view and can be purchased. For the back of the store, Barrington created a wallpaper, and for the front window, a painting on burlap, which is installed next to the usual items on display in the vitrine. Nina Canell and Robin Watkins’s new video Energy Budget (2018) centers on the use of female ostrich feathers to create a dust-free environment in a car manufacture. At Parcours, it is installed inside a car ramp leading to a space underneath the Congress Center.

GP: Did you pick a specific theme for this year’s Parcours, and if yes, why?

SH: During my site visits to Basel, I noticed the many empty stores and spaces that are currently undergoing transformation. Our use of public space post-pandemic is changing, and so is our behavior as citizens in urban spaces, be it in Basel or in New York, where I live and work as director of Swiss Institute. With this observation, as well as my sense of artists’ interests at this moment, I decided to focus Parcours on the themes of transformation and circulation. This includes the circulation of information, ecological changes, globalization, and migration, but also spiritual and metabolic flows.

GP: This year you’ve specifically worked closer to the Messeplatz and investigated already-existing places such as shops, a hotel, a restaurant… What was the starting point of Parcours 2024?

SH: I want Parcours to feel inviting, to feel relevant both for the city and citizens of Basel, and for international visitors. The themes of circulation and transformation that the artists are exploring are site-responsive to the local context, but also connect Basel to other locales. In the cave underneath Volkshaus, the collective Tromarama has installed a work consisting of woodwind flutes that are activated every time someone posts #nationality on X (formerly Twitter) to play a song that children in Indonesia are required to learn to graduate. Anh Trần’s paintings explore the connections between abstraction and spirituality, and they were specifically created with the Clara Church in mind, where they are exhibited in the front choir. Stephanie Comilang’s installation in the window of the online media outlet Bajour, which includes fresh bouquets and embroideries of the flowers of mangoes, mangosteen, and pineapples in a style mimicking butterfly vision on piña cloth, speaks to migration and trade routes. Iris Touliatou’s water fountains installed inside a casino link to the circulation of water and money, and their withholding when water is privatized or people are in debt. The starting point of Parcours were artworks and practices I find relevant, and locations that speak to Basel’s specificity and to how it connects to the curatorial framework of circulation and transformation of information, goods, and people.

GP: What do you think of projects related to art fairs but more on the periphery, such as sculpture parks or screenings?

SH: Thematic sectors can offer a specific focus and curatorial vision and invite audiences to engage with art outside of the fairgrounds, and with the city itself where the event takes place. The dialogue between the artworks and the city, but also visitors and locals, produces unexpected moments, which I love. Public space is not static; it constantly changes architecturally, legally, ecologically, and in terms of its use, access, and meaning to different people. A project taking place in public space, especially when what is considered public cannot be taken for granted, can prompt interesting questions through artworks and the lens of artists.

GP: Do you think Parcours can be seen as a sort of arena for deepening knowledge and thinking about contemporary art?

SH: Parcours brings together a group of very different artists who each in their own right are making relevant work. I hope that visitors will find new artists or see works by artists they love in unexpected settings. This shift in setting, by moving artworks outside and into public spaces of quotidian use, can offer new perspectives both on the art and on those spaces, how we use them, how they shape us, and how we might want them to be in the future.