French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan traveled in circles that often overlapped with the art world. He mingled with its major figures – Picasso and Dora Maar, among others — and personally collected paintings and contributed to the Surrealist magazine Minotaure. Given this, it’s not surprising that the distinguished, if also often-contested, figure and his ideas are being explored in a museum context. Although it’s difficult to pare down complex psychological terms, the exhibition at Centre Pompidou-Metz highlights the “greatest hits” of his career. The premise is more about using his work as a vector for discussing sex, identity, gender, and power in art than indoctrinating the public about twentieth-century psychiatry. “Lacan, The Exhibition: When Art Meets Psychoanalysis” provides a framing device for a selection of works that sometimes explicitly engage with his ideas, but more often simply illustrate themes he meditated on that preoccupy us still today. The curatorial ensemble behind the show includes two art historians (Marie-Laure Bernadac and Bernard Marcadé) and two psychoanalysts (Gérard Wajcman and Paz Corona), to provide a balanced view between the domains.

Each section treats a particular Lacanian tenet. The show begins with the principle of the “Mirror Stage,” formulated in 1936, which states that our selfhood is confirmed when it’s reflected back at us. One example is Michelangelo Pistoletto’s 1933 work Uomo col Panchetto, a mirror-like stainless-steel surface that actively engages the viewer’s reflection alongside that of a swiveled male figure embedded on the surface: here we might feel a sense of self while being estranged from the other. The next section shifts into the concept of “Lalangue”- a neologism invented by Lacan to describe wordplay – which investigates the slipperiness of linguistics. While some of the double meanings are complicated to parse from French in translation, René Magritte’s painting Querelle des Universaux (1928) accessibly disrupts the link between objects and their names through an ensemble of stones inscribed with random words (canon, horse), rendering the arbitrary and absurdist nature of language apparent.

“The Name of the Father” section, a concept that Lacan articulated in 1950s, deconstructs the notion of patriarchy and the Christian tradition of an all-powerful male figure. Overrun by female artists, this section seethes with a kind of dismantling glee. There’s Camille Henrot’s 2015 watercolor Tycoon, in which assorted arms reach into the frame to grip a bearded male nude by his elbow, his mouth, his privates. There’s Claude Cahun’s black-and-white photograph Le Père (1932), a disquieting effigy built primitively on the ground. There’s Niki de Saint Phalle’s book Mon Secret (1932), splayed open to a page in which she cites Lacan by name while telling her mother about the film she made about her sexually abusive father two decades prior, Daddy (1973).

Lacan’s “Object a” (“a” for “autre,” or other) is an articulation of the unattainable object of desire, itemized via representations of the phallus, breasts, and body fragmentation. Explicit works by Man Ray (the silver erection in Presse-papier à priape, 1920/1966) and Louise Bourgeois (the suspended rubber genital-ish sculpture Fillette (Sweeter Version), 1968–99) engage with corporeality as something tangible and primordial. By contrast, Sarah Lucas’s 2019 twisted pantyhose-encased sculpture China NUD 3 and Hans Bellmer’s 1960s-era preparatory drawings (superposing thighs/faces, eyeballs/backsides) create a strange and unsolvable visual riddle of the body.

The display of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866) is a pivotal part of this psychological safari. Lacan and his wife bought the painting in 1954: in their possession, they kept it hidden behind a discrete wood panel. This work is as astonishing as ever in an era when female bodies are still treacherously policed. The iconic painting communes with more contemporary works where the vulva is exposed without shame, such as Valie Export’s Aktionshose: Genitalpanik (1969–2001), in which she’s fully unzipped to reveal her pubic hair, or Deborah de Robertis’s 2014 Mirroir de l’Origine, a photograph of the artist bearing her vulva at the Musée d’Orsay beneath the hung Courbet painting, with her gold dress — same hue as the frame — riding up to her waist.

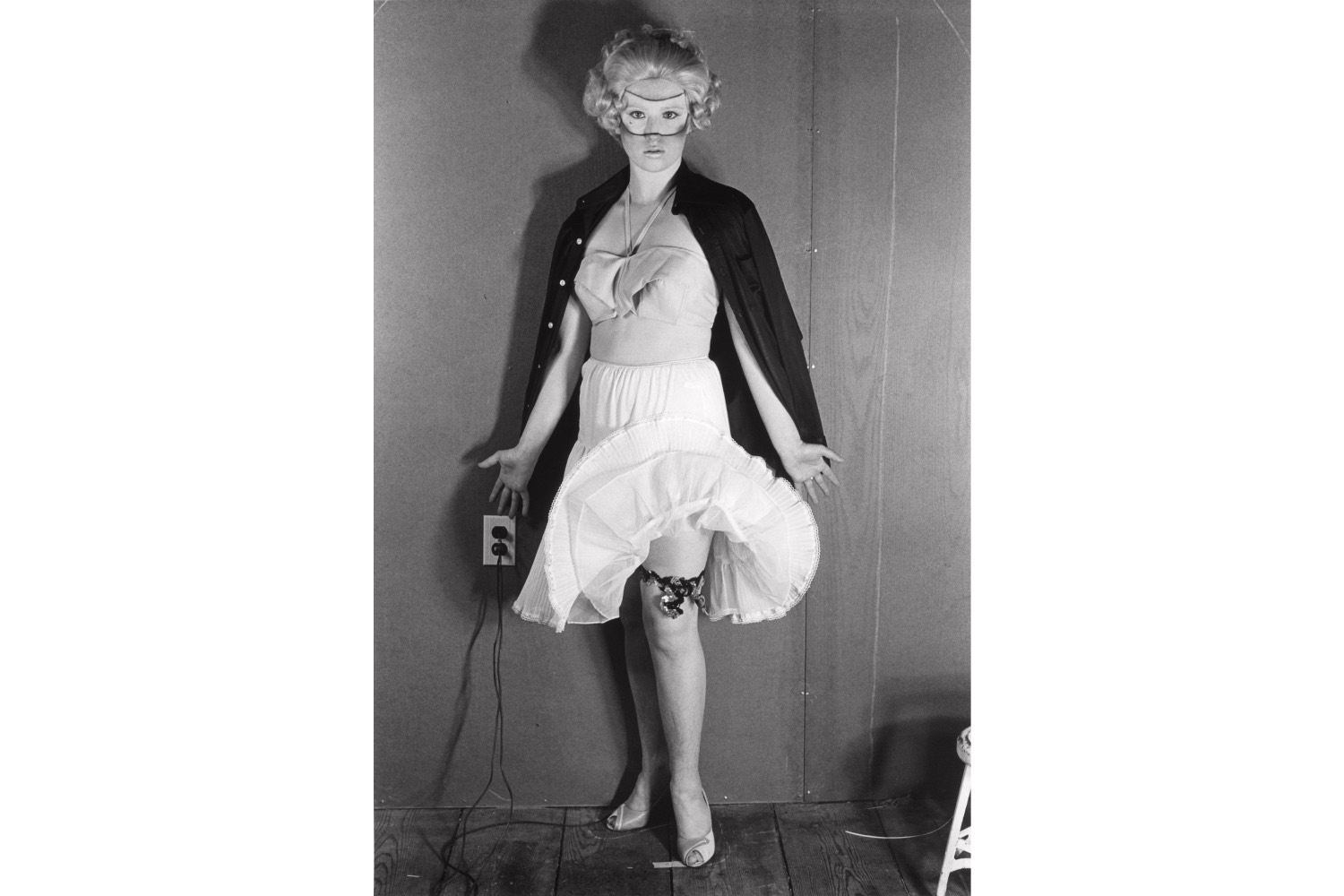

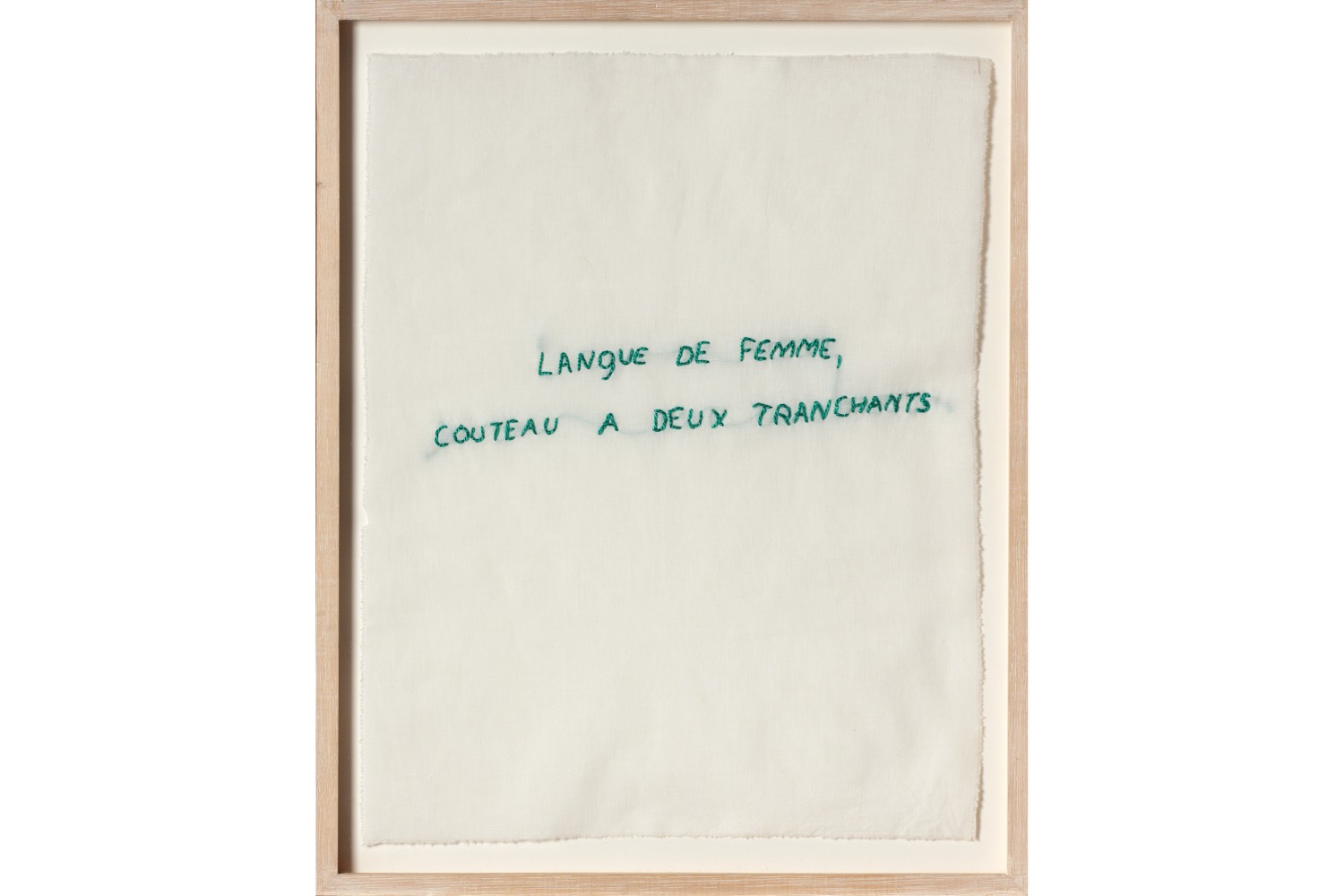

“The Woman Does Not Exist” section is dedicated to Lacan’s incendiary-sounding phrase, meant to elucidate that there is no essentialism to womanhood, not that women are fabricated. Annette Messager’s embroidered series “Ma collection de proverbes” (1974) cheekily mocks the misogynist stereotypes that have run rampant in the past (sample: “What is worse than a woman? Two women”). This section flows into “Anatomy is Not Destiny,” where the performativity of gender is revealed as a queer retelling through works by French visual artist Michel Journiac, in which he dresses as differently gendered characters, and Nan Goldin, who lovingly chronicles drag queens performing at a club in 1970s Boston.

After a tedious section on Lacan’s fixation with the Borromean knot, the visit concludes with what is dubbed a “cabinet of curiosities,” illustrating how Lacan remains a touchstone to creatives today. Will the viewer come away with a firm understanding of Lacan’s theories? Not more than scrolling through a Wikipedia entry — though this is certainly more gratifying. The premise ultimately allows for an exploration of our ever-mystifying minds and bodies, and our inexhaustible obsession with decoding them.