Anemoia — the nostalgia for something, future or past, that you’ve never actually known — is a term coined by the poet John Koenig in 2012 in his Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. A portmanteau word derived from the ancient Greek words for “wind” and “mind,” it suggests an inability to completely inhabit the present. It’s a perfect phrase for the early internet age, the place where these five artists live, against a looming emotional background of environmental apocalypse. While many twenty-first-century social and artistic projects directly address the grief of extinction and ecological catastrophe, the curatorial group Four Three Three succeed in capturing both our era’s psychic distress and the possibilities it might suggest for exploration, adaptation, and invention.

The Iranian artist Sahar M. Abadi’s twelve-minute video loop Where We Were (2022) smashes the viewer’s perceptions of direction and time as her camera pans slowly across a Styrofoam model of ancient temples, or ziggurats, constructed by Gilgamesh, the King of Uruk, who was one-third god and two-thirds human. Both the architectural model and the cinematography were inspired by Abadi’s reading of The Epic of Gilgamesh, written in ancient Akkadian more than four thousand years ago. The screen is divided in half; the top half of the screen is further divided into two panels. On the lower part of the screen, the camera moves slowly across the intricately patterned facades of imagined ruins. With this slowness, perception is skewed: Is it the camera or the model itself that is moving? The top-right panel surveys the same model in a vertical pan at a much closer distance. Time, it seems, is tearing apart. Meanwhile, the Arabic characters for a series of numbers flash white-on-black in the top-left panel: a countdown, perhaps, or a visual pun, reminding the viewer of the time-based nature of all video art. “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” the artist told me via email, “is a strange and moving story. It recalls remote times, places, and people who are not fully human. It vibrates with a universal fear for death.”

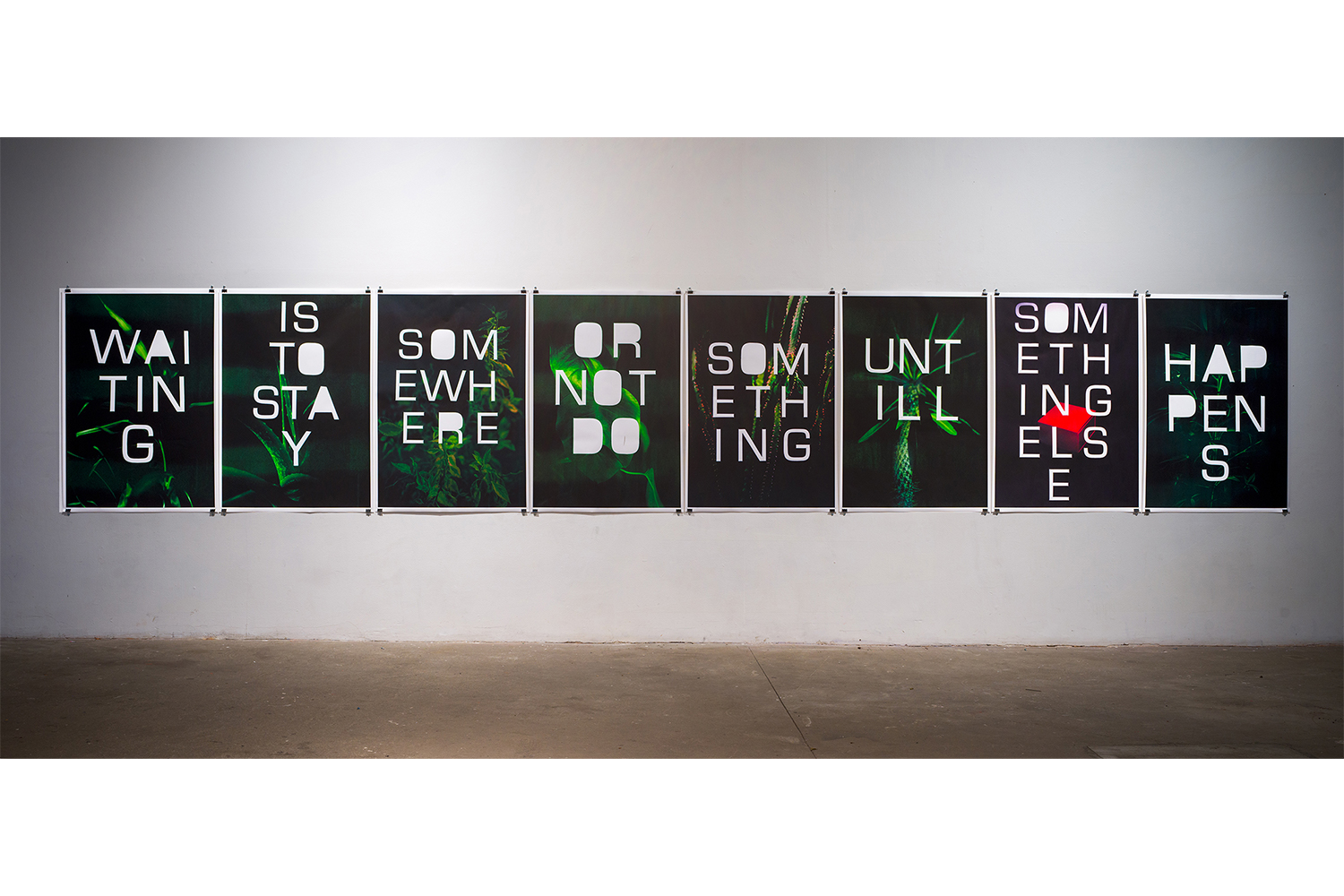

WAITING/, begins Niusha Barahimi’s eight-panel, text-based work Photosynthesis (2023), IS TO STAY/SOMEWHERE/OR NOT DO SOMETHING UNTIL/SOMETHING ELSE/HAPPENS. These huge, skinny, white sans-serif letters emerge out of an inky-black background streaked with flashes of chlorophyll-green. Barahimi, who works between Tehran and Paris, creates these images with an analog camera. “The exposure of light and time,” she told me, “To bring an analog photograph to life, is a righteous coincidence to the subject of waiting and remaining in expectation.” Photosynthesis is the process through which plants transform light into chemical energy. It is also the source of the earth’s quickly diminishing fossil fuels. Barahimi’s work alludes to distraction: the way that dictatorships exert control through diversion and censorship. In this work, the present is forever postponed or suspended.

The Los Angeles artist David Daigle’s imposing wall sculpture PETROL (2022) is an inflatable raft of debris, partly synthetic and partly human. A long swathe of black human hair is expunged from a hole; an old touch-tone telephone keypad is stuck in its center. Daigle, an artist with a background in advertising photography, uses his multimedia practice to explore the space where desire, consumer images, and the self all collide. An earlier black-and-white photographic series, “The Beauty of Decay” (2000–15), depicts ordinary used and discarded objects with a heightened appreciation of form, beauty, and classicism. In PETROL, the discarded objects are all thrown together, encased in plastic, suggestion horrific genetic mutations from chemical leakage. But in the event of emergency — our perpetual state of emergency — could it also work as a life raft?

Captured in the waters off the Galapagos Islands and on the Channel Islands, Taylor Griffith’s arresting video loop Staring into the Abyss of an Archipelago (2023) switches between views of the ocean’s depths and deep outer space. Exhibited on a small, generic black TV monitor, in less than two minutes of footage this astonishing work spans the breadth of our seeable universe. Growing up as the child of ocean exploration submersible devices, Griffith’s artwork is made within a space he has created between visual aesthetics, spirituality, and science. He’s frequently been invited to join scientific expeditions as a visual artist. “Often,” he emailed me, “I am the only artist in these spaces, but scientists are realizing the value of working with artists at sea, as was common in the early days of ocean exploration.” These early expeditions were intent on discovering exploitable resources. But scientists now recognize the value of new perspectives that emphasize the ocean as living with us, not for us.

At first glance, the Los Angeles-based Brazilian artist Andrea Nhuch’s beautiful speculative sculptures seem to depict states of environmental degradation. Nhuch has long been fascinated by the colonial/industrial histories of rubber and plastics. Her spare and elegant works are made from scavenged tree trunks and twigs entwined with sheet metal, rubber latex, and pieces of plastic. The viewer is jolted, at first, by these stately displays of the sadly familiar juxtaposition of the natural world and human debris. But looking closer, Nhuch’s works suggest an entirely new form of beauty: one that might be found by accepting the world as it is, where nature and human synthetics are inextricably bound. In Tree Legged Support (2023), one of the stems of a bare tree branch is painted emergency red. And in Amuleto da Sorte (Good Luck Talisman) (2023), Nhuch creates a fetish-like object made out of twigs, plastic turf, and rubber tubing. Leaning on and bursting industrialized nature (2023) transports an almost-familiar slice of the urban landscape into the gallery. A thick branch of a tree is cemented upright, adorned with debris and partly supported by a piece of sheet metal. Could it be that these permanent aberrations of the natural world actually point toward a form of adaptation? Twenty-first-century birds have been known to build nests with scavenged twigs and shreds of plastic. Far from conditioned despair, Nhuch’s work strikes me as strangely utopian.

The works in this impressive show offer a glimpse of the world as it is: full of survival, alarm, adaptation, suspension, and wonder.