Mexico City has long been one of the world’s most dynamic art capitals, though its performance scene of late has been sorely in need of institutional support. Enter TONO, a new festival of video and performance art, which mounted its ambitious inaugural edition from April 18 to 30. Organized and curated by Samantha Ozer, it featured four video exhibitions and nine performances in nine separate venues across the city. If both video and performance together seem too broad a rubric — comprising most time-based media — TONO’s theme of “Ritmo” (Rhythm) helped lend its sprawling program a sense of cohesion. Music and its attendant subcultures were a focus of most videos on display, and nearly all the performances had prominent soundtracks. This was apt in a city ringing at all hours with the sounds of mariachis and street vendors, a place where rhythm has been fundamental to creative expression since the Aztecs lay the first stones atop Lake Texcoco.

Many of TONO’s projects were also marked by their site-specificity. A gripping performance by Colombian, Berlin-based artist Jao Moon beneath a black volcanic eave of the Museo Anahuacalli, the modernist pyramid housing Diego Rivera’s pre-Colombian art collection, evoked indigenous rituals and sexual fetish in equal measure. Clad in only a beige thong and a red leather mask with lit candles affixed to its crown, Moon twisted and turned as hot wax dripped onto his body, its sound viscerally amplified by a set of concealed microphones. Mexican choreographer Diego Vega Solorza mounted his dance Dorje (2019) at Ex-Theresa, a crumbling baroque church in the city center, which opened provocatively with four fully nude men, lit in red light, contorted so their asses were thrust in the air in poses redolent of the punishment for simoniacs in Dante’s Inferno. At Laboratorio Arte Alameda, meanwhile, Arthur Jafa’s akingdomcomethas (2018) screened in a black-box theater constructed within one of Mexico City’s oldest deconsecrated churches. The two-hour feature, which here marked Jafa’s first solo exhibition in Latin America, is a gripping collage of Black preachers and gospel singers interspersed with footage of devastating wildfires in Southern California, creating an uneasy — and very real — proximity between pleas for salvation and the apocalyptic threat of climate change. This comparison felt all the more fraught on the former site of sham trials for the Spanish inquisition.

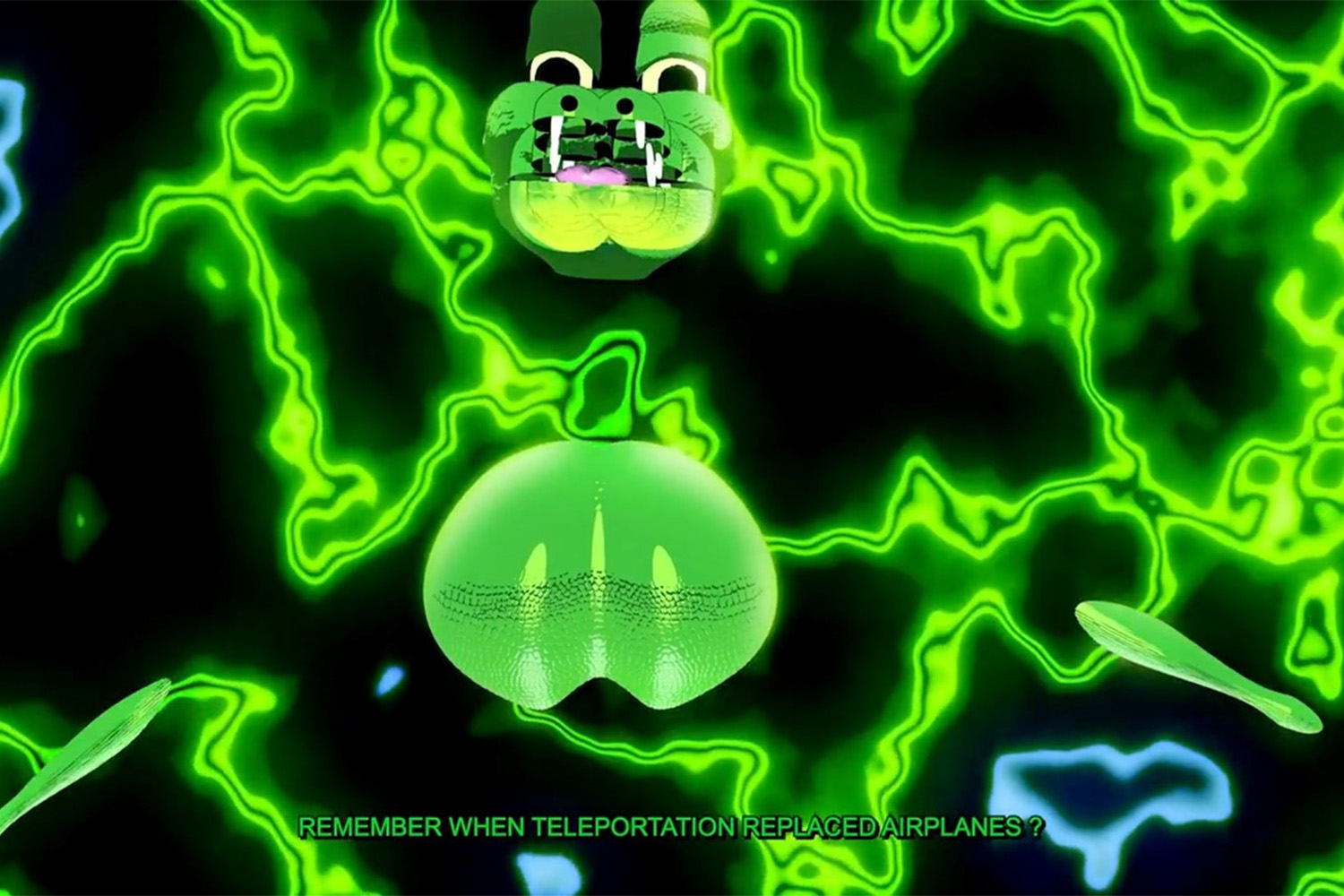

In the afternoons, visitors to TONO could watch a selection of eight videos at Casa Margarita, an Art Nouveau manor once owned by the poet Margarita Quijano. Videos were paired on a loop in four wood-paneled rooms — an unfortunate move for the average impatient gallerygoer, though the pairings teased out a range of connections. In Diane Severin Nguyen’s IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021), a Polish, K-pop-inspired girl band, dressed like twee communards, wander around Warsaw singing lyrics like “If the heart only begins to beat properly when it is broken… how can truth prevail?” The line echoes the title and chorus of Jacolby Satterwhite’s deliriously animated music video We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other (2019), which follows it in loop. Upstairs, Meriem Bennani’s cyberpunk Party in the Caps (2018) documents the family dances of Moroccan refugees living on an imagined future prison island for undocumented immigrants to the US by teleportation. A similarly ecstatic dystopia is central to Santiago Gómez’s standout video Global Warming (2020), in which the artist reflects on the growing popularity of reggaeton — a “hot” genre, both sonically and culturally, for our late-capitalist era — over a chaotic collage of space aliens and killer robots culled from video games. With deadpan seriousness, he asks, “Which will come first, the end of the world, or the end of Despacito?”

The keystone event of TONO was a techno opera by the Mexican artist collective NAAFI, with an electrifying star performance by La Bruja de Texcoco in the role of an indigenous witch. Dressed in a pleated emerald robe and carrying a flaming goblet of incense, she summoned the architect of the National Anthropology Museum, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez (played by Pepx Romero), from a smoking pit of rubble. An ashen zombie, he followed her around the immersive set, installed in a dilapidated warehouse, as both actors told the story of the birth of Mexico City, which the Aztecs built on the islets of Lake Texcoco before the Spanish tore it down and had the lake drained. The witty libretto drew links between colonialism, sexual repression, and environmental catastrophe, and reached its climax in a scene featuring a torture device of hissing vacuum tubes designed by New York-based artist WangShui. This was only the fourth act of the full opera, which deserves a full viewing on an international stage.

The festival concluded with deader than dead (2020), a performance by Berlin-based artist and choreographer Ligia Lewis. A trio of dancers zig-zagged across a stage of yellow gym mats, lit putrescent green, with stiffly jointed movements that resembled puppets doing a demented Tik-Tok routine. The soundtrack segued from courtly baroque music to techno with the pace and pitch of a heart monitor. The dancers seemed to recover full mobility only as they took turns throwing each other’s dead weight across the floor in a disturbing rehearsal of physical violence. Lewis has often dealt with dark humor (or “black comedy”) as well as violence against Black bodies in her work, and both were constantly present here, in gestures of self-effacement and a general atmosphere of threat.

TONO had its share of unpolished aspects, like the screening format at Casa Margarita, but if the large crowds at its free programs were any indication, it has contributed to this vibrant and layered metropolis an exciting new beat.