Prompted by filmmaker Vasilis Katsoupis’s personal awakening about the “dark side of luxury” while staying at a friend’s Lower Manhattan apartment, and the questions such an expertly decorated space prompted about the value of art for sustaining life itself, Inside (2023) is a heist film turned shipwreck. Nemo, the (virtually solo) character played by Willem Dafoe, is an art thief trapped in the high-tech loft of the art collector he is trying to rob — a Robinson Crusoe of sorts, whose expected practices of primitive accumulation turn instead into dispossession and steady decline. While Nemo’s voice-over at the beginning and end of the film defends the enduring power of art, the film’s narrative pits human survival against art’s supposed intrinsic value — its value as art.

It is a generic convention that the heist film would make us side with the thief; and it is the power of Dafoe’s star persona and brilliant acting that decisively channels sympathies toward his resourcefulness, his wit and determination, as well as his unorthodox creativity, regardless of the amount of destruction he brings to the artwork he “misuses” toward his own ends. The conceit here is that the “ecology of care” demanded by the art collection — which includes a timer that waters the plants and a refrigerator that self-reports about dwindling supplies and volunteers energy-saving tips — becomes the very trap Nemo has to escape. This is the same ecology of care employed by the modern art museum, as Fernando Domínguez Rubio argues in Still Life (2020), which hinges on attaching a working object (i.e., an object that produces aesthetic value) to a working subject (an artist who can provide a legible intention to secure their connection to, and therefore the value of, the working object). This, Domínguez Rubio argues, is the only relation that can guarantee the stability, and therefore the value, of the art object, a relationship that ultimately produces a sameness between object and subject.

Indeed, approached from the sensibilities of new materialism — as we see Nemo forced to collect water destined to the indoor plants, eat raw fish from the decorative tank, or understand his own fate as associated to that of a pigeon that, like so many other birds in urban environments, most likely collided with the penthouse’s giant windows and eventually freezes to death on its terrace — Inside timidly experiments with suggesting a flat ontology between subject and objects, one that, however, still clings to the inalienable value of the stranded human, as demanded by generic and cultural expectations. Shot sequentially, on a built set replicating the fictional loft, and with scenes that were created in situ through improvised interactions with the artwork, Inside’s embracing of this ecology of (art) care tests whether it can also extend to subjects other than the art creators themselves, and suggests the film itself should be approached as conceptual art in narrative form: an experimental work of conceptual speculation unfolding in a time-based medium.

Speculation is the key term here: once art, which always speculates about its future, has colluded with the speculative processes of finance capital, Marina Vishmidt argues, it comes under the latter’s specific value-form, that of “self-valorization.” That is, art accrues value regardless of its fate: whether it is intact or destroyed, whether it is an original or a copy, commissioned or part of existing collections.

Leaning on the figure of the maid Nemo unsuccessfully appeals to, as he watches her through a close-circuit TV, and who hides in the building’s recesses to steal precious moments for herself, I am reminded of the critique of the “kinship structures of modernism” (Leah Pires) as seen through Carissa Rodriguez’s video installation The Maid (2018), which follows six of Sherrie Levine’s Newborns (1993) (her reproduction of Brancusi’s sculptures by the same title — Le Nouveau Né, 1915–20) into a variety of spaces of “care”: from collectors’ homes to storage rooms in institutions of high art. Rodriguez extends Levine’s critique of the patrilinear right to authorship by focusing on the sculptures, rather than their caregivers, as her floating Steadicam slow pans and tilts approach the Newborns in their own (alienated) environments as quasi-animate beings, quietly awaiting human care or perhaps questioning if it’ll ever come. In Inside, this is the position occupied by Nemo. Yet while The Maid questions this ecology of (art) care, Inside takes place fully within it, even as it wrestles with some of its premises.

At the same time, the artworks’ collection itself — expertly curated by Leonardo Bigazzi — seems to tell a different story, one that performs an immanent critique of art’s own undeniable and unstoppable speculative mode of production, one where value is still relentlessly generated even when spectacularizing the art’s destruction or flaunting carelessness toward it.

With old-school language we could say that the film’s narrative attempts a troubling of the vexed relationship between function and ornament: what’s hanging on the walls is no longer sacred, and even a Maurizio Cattelan piece such as Untitled (1999), in which he taped his own gallerist to a gallery wall, has to be “set free,” in a scene that came to Dafoe himself as he was working on set — although we might be left wondering whether it is the work or the gallerist who should be metaphorically walking away.

As a whole, Bigazzi’s curatorial choices push back against this facile distinction, while keeping in play the relationship between ideas of property and propriety inherent in the very concept of filmic prop: he had to negotiate separately with each artist the terms of their work’s appearance, and the way in which it was going to be “misused” and possibly destroyed during the shoot. Some artists embraced the idea of this very deterioration becoming part of the work. By curating blue-chip artists (whose very label advertises the open secret of their imbrication with art’s speculative mode of production) alongside emerging ones invested in a more pointed social critique, and who might have an uneasy relationship with the speculative processes of the artworld, the film’s art collection has the ability to gesture toward the “outside world” much more than Nemo is granted the ability to do, even when he does so with a black sharpie that, literally, spells it out. The set’s art collection is full of works that, for instance, push back against expectations of their own permanence or the tokenism of figuration as practiced by BIPOC artists, such as Maxwell Alexandre’s painting Se eu fosse vocês olhava pra mim de novo [If I Were you, I’d Look at Me Again] (2018), on brown craft paper, which, ironically, is duplicated in a (more permanent) large-scale photograph of the collector, his daughter, and his dog standing in front of it; works that deploy the language of (social) abstraction to reclaim its underlying collectivism, such as Amalia Pica’s Memorial for Intersections #15 (2015), which takes exception with the Argentinian dictatorship’s banning of Venn diagrams because of their ability to map collective action; works that address situations of political and existential limbo, such as Adrian Paci’s photograph of refugees in a state of “temporary permanence” – Centro di permanenza temporanea (2007) –, as they crowd on the boarding staircase of an aircraft that, however, is not there.

The two-pronged intention for Bigazzi’s curation hinges, on the one hand, on the ability of Inside’s art collection to tell us something about the collector (an intentionality that, however narratively motivated, perfectly aligns with Domínguez Rubio’s analysis of the art world’s dependence on linking subject and object) and, on the other, on plot points that can be best served by artworks that explore similar themes: entrapment, suspension, sheltering in place (like Joanna Piotrowska’s “Untitled” 2016–17 photographic series) and whose social critique has the potential to continue to resonate even once they are unceremoniously destroyed. It is this very resonance that has the greatest potential for the film’s immanent critique, which hovers between embracing value accumulation in the image (think of Luchino Visconti filling drawers and cabinets with original artifacts in The Leopard (1963), although they are never shown in the film’s diegesis — in simple words, Inside might be rich because it contains valuable work) and a critique of these very processes of accumulation performed by the image of the artwork itself (Inside might be an image of wealth).

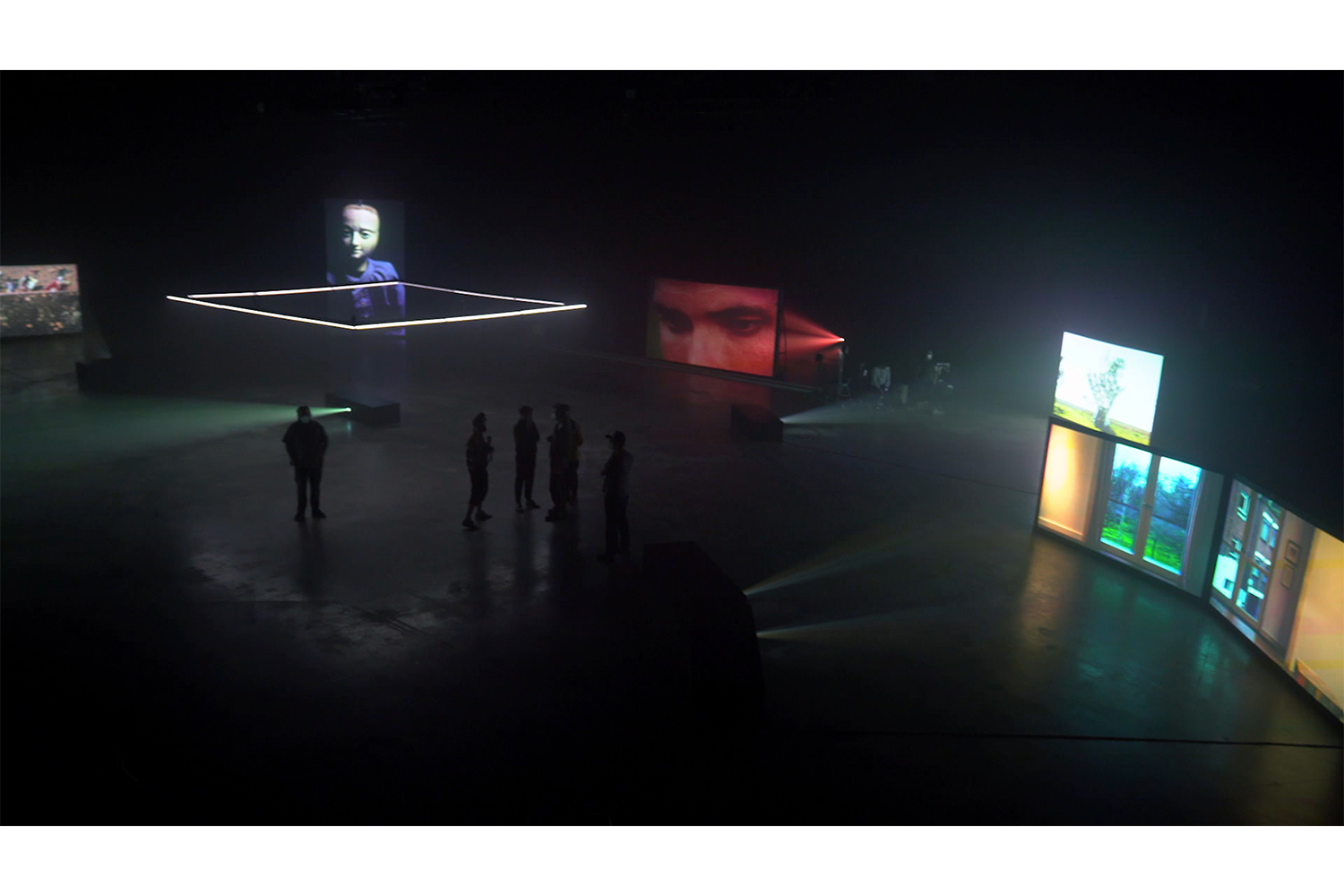

This is the conundrum of immanent critique, an immanence that in Inside becomes a project with architectural implications. The penthouse itself includes a series of crypts: a video installation room in an unclear location, where Breda Beban’s two-channel I can’t make you love me (2003) plays continuously for no one to see — an expenditure of resources the refrigerator might object to — and an architectural “crevice” Nemo reluctantly passes through, only to find a rubber mummy of the collector, a book — William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell — and the previously unlocatable Schiele self-portrait which was the main target of the heist — all objects that, more or less seriously, strive toward the eternal. There is also a basement of sorts Nemo visits in a dream by descending a replica of the boarding staircase featured in Paci’s work, where the collector greets him warmly but also proffers a series of platitudes typical of an art opening, even though in this case it features the work of “socially conscious” artists (in this case, PROTOCOL 90/6 by MASBEDO, i.e., Nicolò Massazza and Iacopo Bedogni, 2018).

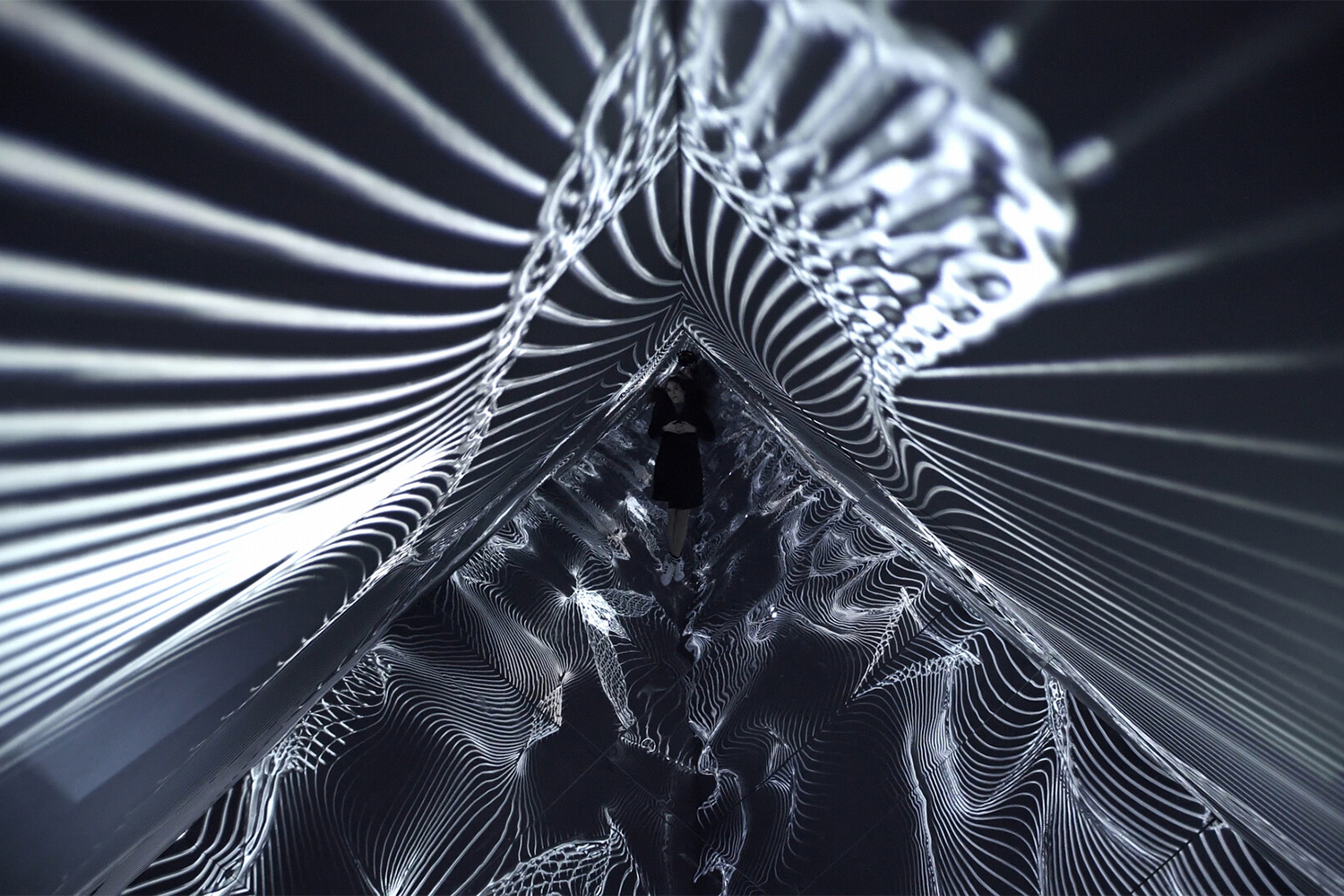

Ultimately, the film’s immanent critique is also cryptic: it does not so much hinge on Nemo’s quest for survival and eventual escape, but is rather embedded in the curated artworks themselves, making its place within them, like a moth, which Bigazzi describes as “an animal that hides itself in the structure of the architecture of the house and through this attitude finds its own way of living” — an allegory made present in Inside through a moth costume by Kosovan installation artists Petrit Halilaj and Shurte Halilaj, Do you realise there is a rainbow even if it’s night!?(coral) (2020), which Nemo eventually wears to protect himself from the freezing temperature.

By seeking to serve the narrative demands of the filmmaker’s conceit, Bigazzi has perhaps created a space for the collected artwork to perform its distance from the project of primitive accumulation that the collector has, however, already performed. At the same time, with the exception of a handful of recognizable works, this critique might remain obscure, unclear, or neglected when viewers do not know the artwork, its context, or its value. Still, they may wonder about the art-world value of any and all elements of the set design, at the same time that they might question their own investment in this value-seeking operation: Does it really make a difference what Nemo is using for his escape? This is indeed an immanent critique: an undecidability about the processes of value creation that conflicts with the film’s narrative of survival as well as the art world’s speculative processes. Ultimately, it is encrypted also in Dafoe’s brilliant performance, which supports and embraces this immanent critique by rejecting the very processes of value creation relative to his craft: for example, method acting’s reliance on psychologizing the character, fetishizing the intrinsic value of their backstory, their real or fictive “lived experience,” and his decision to focus instead on interacting with the objects in their environment, in the set he lived in, for a whole month, and interpreted irreverently, creatively, and with precious wit.

Perhaps, in all its immanence, the moth is, indeed, the way out.