In Latifa Echakhch’s essay titled “The Concert,” written to accompany her contribution to this year’s Swiss Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, she writes, “This is the sound I produce, and in hearing it you become that sound.” And in conversation with musician Stephen O’Malley, Echakhch describes this sonic embodiment phenomenon not as an acoustical stretching but as atomization. “Through those micro-fragments within [sound] we rendered it immense, almost infinite,” she declares.

In practice, the spectacle synthesizes more impalpable sensorial dimensions — a culmination of what is perceivable to an audience. As with all underground music scenes, sonic ecologies, and sonorous frames of reference, the spectacle is radically sharpened through the temporary bonds formed between the audience, scene, and performer.

Known for giving prominence to the spectacle as a means for preserving Italian heritage sites, and for their sustainable activities within Italy’s ecological landscape, Terraforma and Nextones unfurled for a rapt public of more than three thousand guests after its two-year break. Their initiator, the Milan-based agency Threes Productions, has resumed its year-round programming of music festivals and artistic interventions such as Una Boccata d’Arte throughout Italy.

With Echakhch’s treatise in mind, what micro-details, haunts, or divulgences arise when taking residence in an abandoned quarry in northern Italy for Nextones? Or while raving for three days in the Baroque-style Villa Arconati gardens during Terraforma? Based on this image of the spectacle, the stage, and its embodiment, what happens in the experience of encountering sites of historical significance — exemplars of temporality or lavish modernity — or when shown to stir up a response to the shared and immeasurable present?

The most distinctive feature of Terraforma is its magnificent setting: a palace and holiday home acquired by the Milanese Arconati family of Italy’s noble societal class. Years of on-site restoration have renewed and salvaged some of the original sculptural masterpieces that make up the marble-sandstone theaters and fountains plotted around the grounds. The villa’s water systems, in particular, are critical markers of Baroque civil-technological sophistication that are cataloged in Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus. Amid such marvelous water-system engineering on display, Italy’s state of emergency hit after the festival, and water rationing throughout the canton began as heatwaves pushed the national mean temperature to 2.88 °C above average.

Shift to day two of Terraforma, where the prophetic Expat, starring Mykki Blanco and Samuel Acevedo, is “forcing audiences [to] embrace the now,” linking domestic labor, class division, working-class households, a history of racial profiling, access to reproductive healthcare, the climate crisis, and so on to that incandescent now. Disarming and frank, the duo addressed the audience with anecdotes and scenarios in their helter-skelter style resonating across a larger US context – clearly signaling ways to cope with such despairing circumstances. “White supremacy causes climate change,” Mykki Blanco vehemently recited beside Acevedo’s guitar riffs paying tribute to rock and roll and its offshoots, “We need systems based on regeneration, not extraction!” As this blunt force undertaking came to a close, a hard trance track barreled out of the speakers and the audience briefly descended into a rave.

Another significant on-site restoration is the Labyrinth, which hosted Amnesia Scanner’s theatrical display and newest collaboration, AS Unplugged, with artist Freeka Tet. The work is based on their 2020 release, Tearless, known as a “break-up album with the planet.” In the middle of a hedge maze, I pushed to get closer to the Labyrinth’s center, yet was overcome by a somewhat nebulous and frantic feeling among the few thousand festival attendees. In retrospect, this impression is also conveyed in Amnesia Scanner’s lyrical derangement: “You will be fine if we can help you lose your mind.” A flagrant contrast to the steady buzz of cicadas on the grounds of this villa di Delizia.

Nextones, however, goes for a more pensive experience for spectators. Throughout the week, we visited the region’s ruin-like chapels and hydrographic canyons where Rrose played a rendition of James Tenney’s “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion”, attended evening sets with Marina Herlop and SKY H1 at the Tones Teatro Natura in Italy’s Ossola Valley (which was once a quarry used to extract ancient marble), and took a pedagogical hike describing the region’s history of cultivating “white coal of the alps,” otherwise known as hydroelectricity. The main thematic course took a more communal and sonic attunement with the landscape overall.

Artist Verynicensleazy’s wind harp, ARPABONG, is designed to use airflow or smoke to sound the instrument. Halfway through a day hike around Lago di Agaro, we sat and listened to oscillating instrumentation made from the wind’s intensity. Our location, we learned, was near a valley that was once home to a small community that was displaced to build a dam as part of the industrialization and spread of hydroelectricity plants throughout northern Italy. Mountain communities of the Italian alps have long been subject to relegation in Italian society and still harbor difficulties today, having experienced an eighty-percent decrease in snowfall last winter along with the worst drought in seventy years.

To wrap up a week of activities and shows, foodculture days presented Tastetones, a workshop on the food and ecology of the rural alpine area. Margaux Schwab of foodculture days, collaborating with “low-tech” enthusiast Daniel Parnitzke and the women-led collective Fortuna Forest, learned about “the deep time and genealogy of the region.” Fortuna Forest foraged ingredients for a menu inspired by Croveo village’s annual witch festival memorializing the thousands of women who were killed during the Italian witch trials for their knowledge of the region’s endemic plants and alchemy. And Parnitzke tells us that “we urgently need to do better with less,” before inviting guests to cook with clay from Devero’s clear-water torrents using a stone oven assembled for the workshop. Together they illustrated modes of being, “connected to the vegetal, cultural dynamics, and minerals in Ossola Valley,” said Schwab.

Sharing similarities to the music festivals, Fondazione Elpis with Galleria Continua curates a series of artistic interventions under the name “Una Boccata d’Arte” where Ruggero Pietromarchi of Threes Productions invited artist Hanne Lippard to respond to a ruin in the small village of Basilicata this summer.

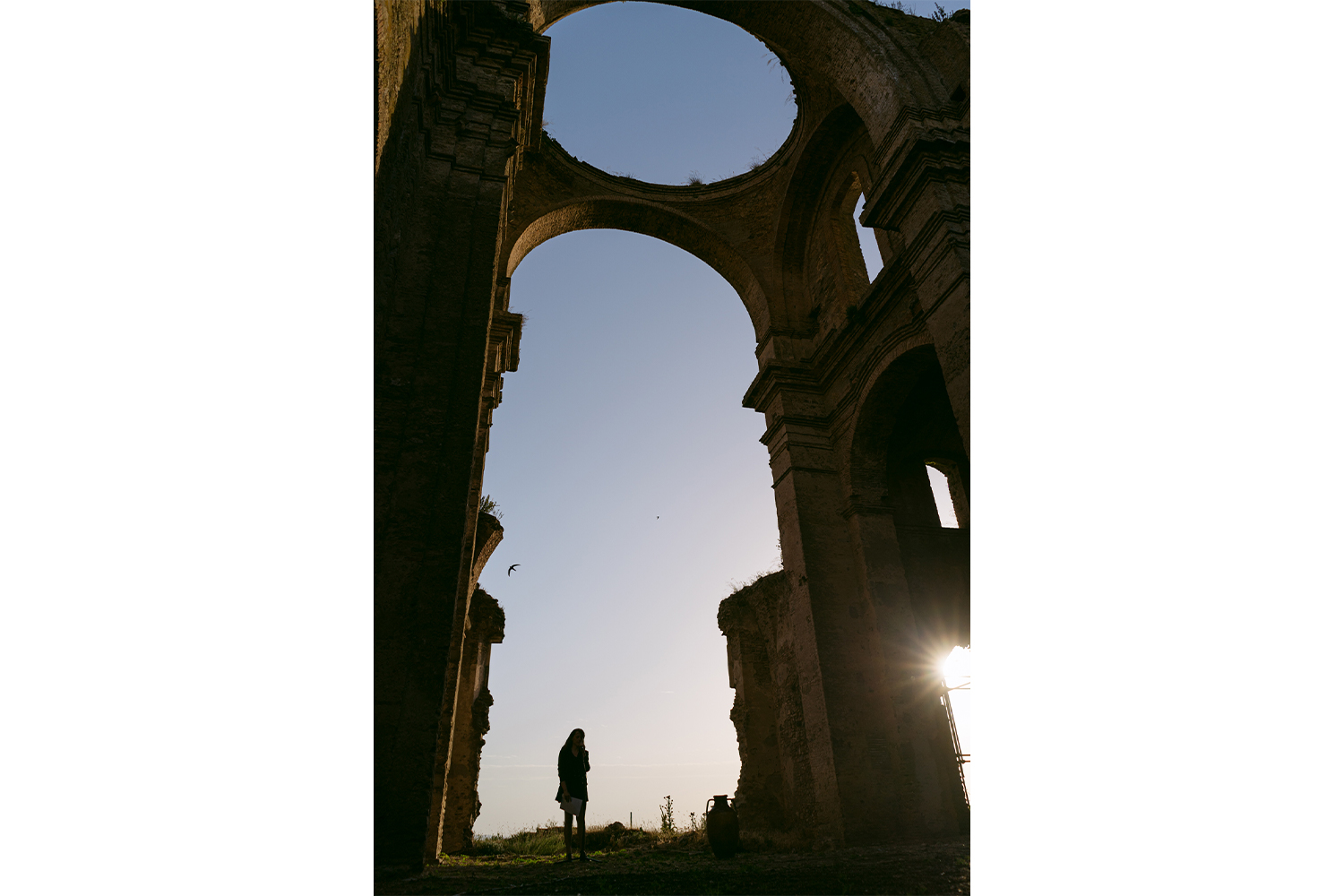

“The concept of the series is to kind of revive or revitalize these small villages that are somewhat abandoned, and this is a huge issue in Italy,” Lippard explained to me in her Berlin studio. She was working with, “this dead ruin that was destroyed due to a series of earthquakes and is currently occupied by birds with their nests.” Recalling her initial visit to the unobstructed site, she said she “found the whole place really eerie.” From the inside of a terracotta clay vase made in the region, Lippard’s hiccups from earlier work and Ruin (2022) sound in intervals. In the vase, we hear Lippard’s voice as she contemplates the ruin as, “reconstructed through speech and memory — telling of the past.”

Meant to be a sixteenth-century church atop the ancient village of Grottole, the failed site now in ruin “never had a ceiling, and there’s this structure left in the shape of a circle that frames the sky” Lippard described. Pointing to celestial openings is something Lippard often recalls in her work in relation to body orifices, speaking, and containment. Lippard made a circular soil imprint on the ruin grounds to mirror the ceiling which she sees as a sort of grave and reference to the region’s archeological accounts of prehistoric cave dwellings.

“To go there and hear some voice speaking,” Lippard says, “is like whenever you hear a voice lingering in the space without the body — it is always weird.” The eerie impression of a disembodied voice or the attempt at recalling the spectacle is like a ruin, there are disparities between what was made and the body’s susceptibility to perceiving what transpired. Echakhch writes “that sound of which we speak is never anything but the representation we make of sound that has been heard and is already gone” – a process of remembrance and memory’s immensity.