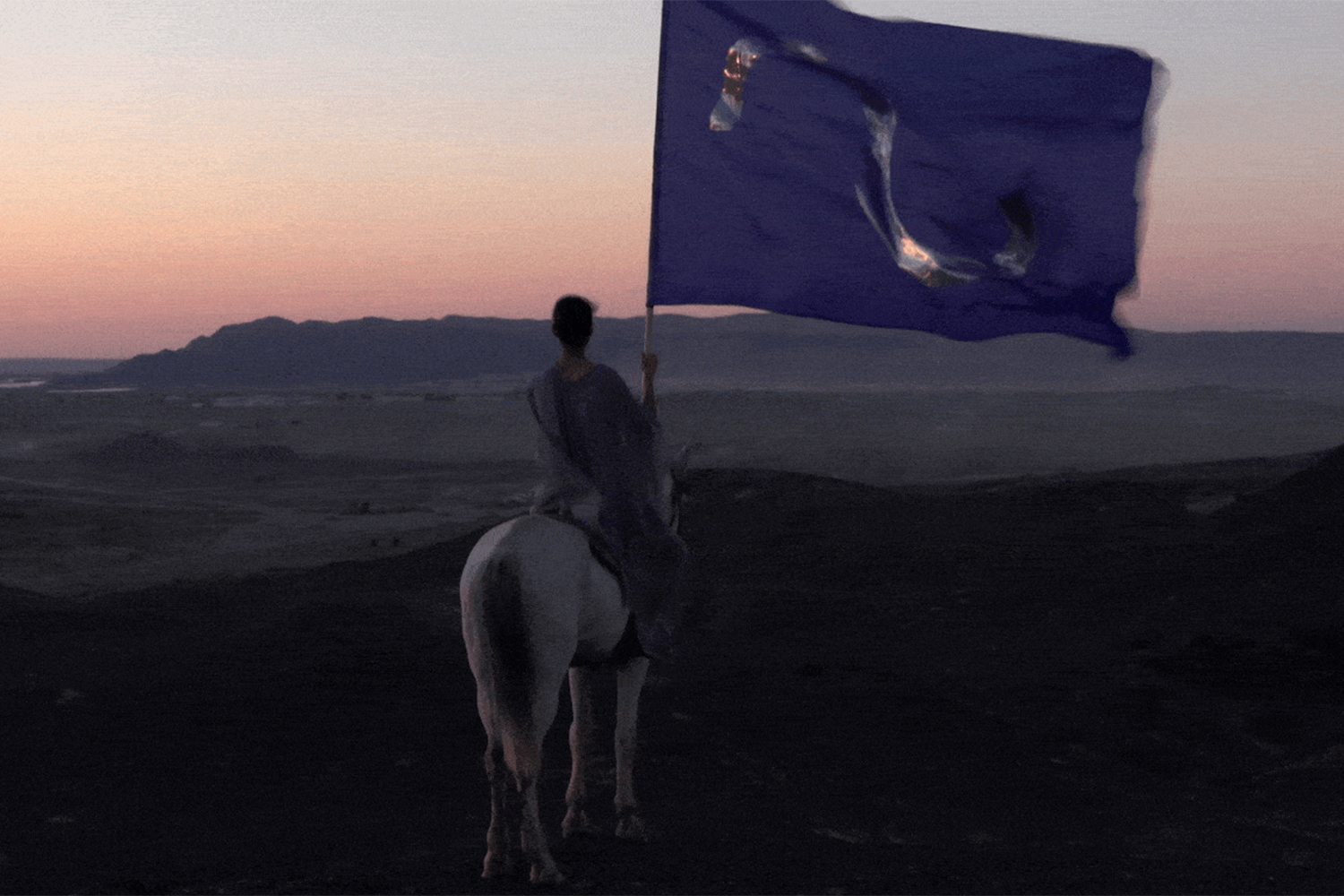

Ooh, we know some bad words, don’t we? We don’t get to know exactly which bad words the artist is referring to in the title of her show, but one may assume we are invited to speculate. After all, apart from being a videographer, Cytter is also a wordsmith, a storyteller of remarkable ability, and, in one segment of the show, she displays all of the books she produced. There are quite a lot, from novels and children’s books to poetry and self-help literature. The title of the exhibition is from Cytter’s ten-minute video Bad Words or when you wake up and realize that you are late to your job interview with your best friend’s ex and you are not a lesbian, but the product of a patriarchal society that’s conditioned you to see women as sex objects (2021). After working with longer video formats and even video works in series, Bad Words marks a return to the short format of earlier works, with plenty of (self-) references thrown in, from campy titles and styling to excessive grain and ostensibly clunky editing, showing off a retro video look, with cameos by Marilyn Manson (on a sweater) and Justin Bieber and his wife lip-synching (“a really bad word”) on TikTok. Oh, and “God” sends text messages (“Did you see that?”) that apparently enter into dialogue with the slogans on a character’s sweater (“HELL NO”).

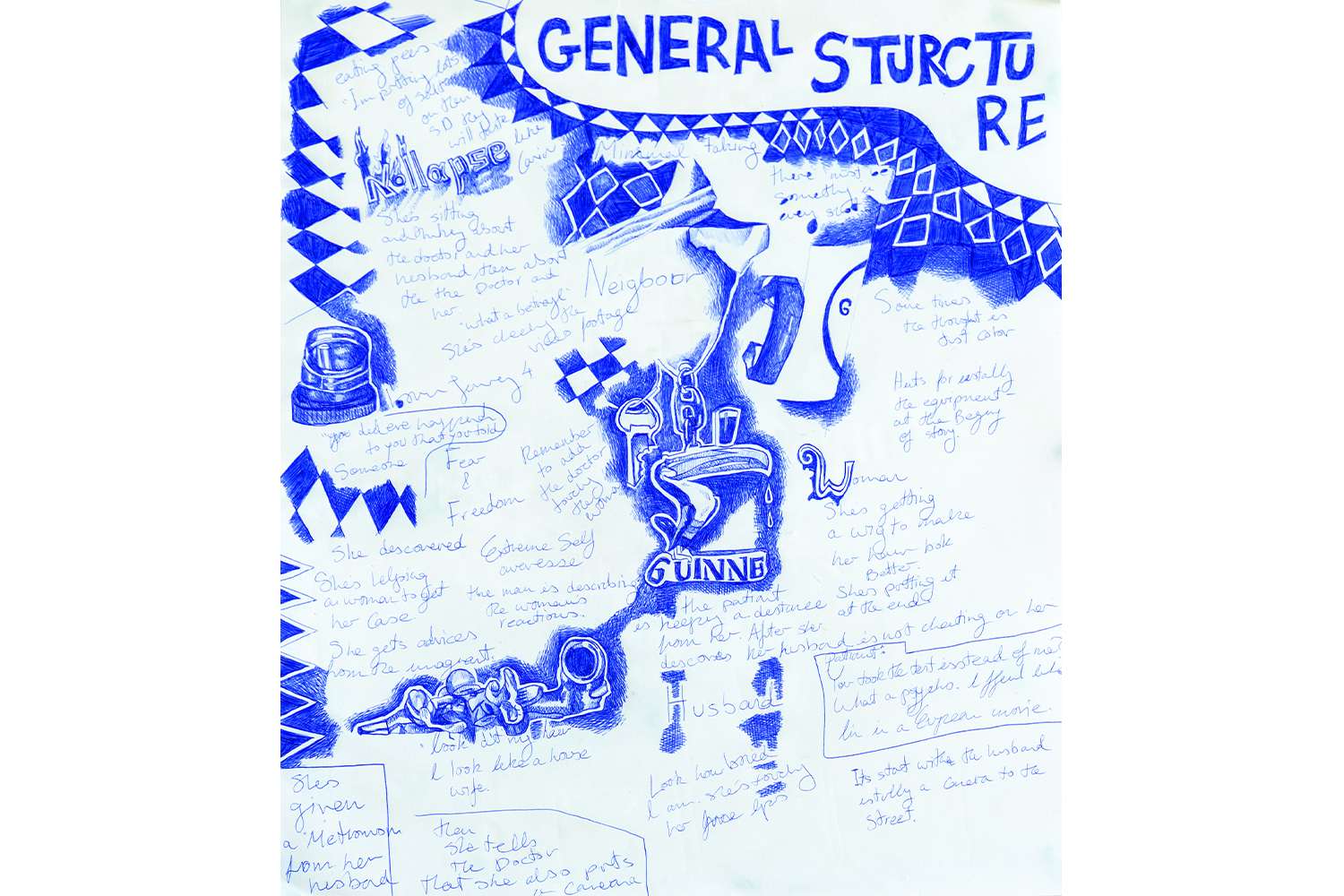

The artist excels at complicating narratives, often by layering several stories with conflicting plots or punch lines (or the absence thereof) and creating complex and incompatible nonlinear or cyclical structures. She plays with the audience’s awareness of varying dramaturgic conventions in different genres of cinema, television, or YouTube videos, and she confronts or subverts these, introducing a sense of cultural alienation, even if it is not clear exactly who — the characters, the artist as director or writer, or the viewer — is being alienated.

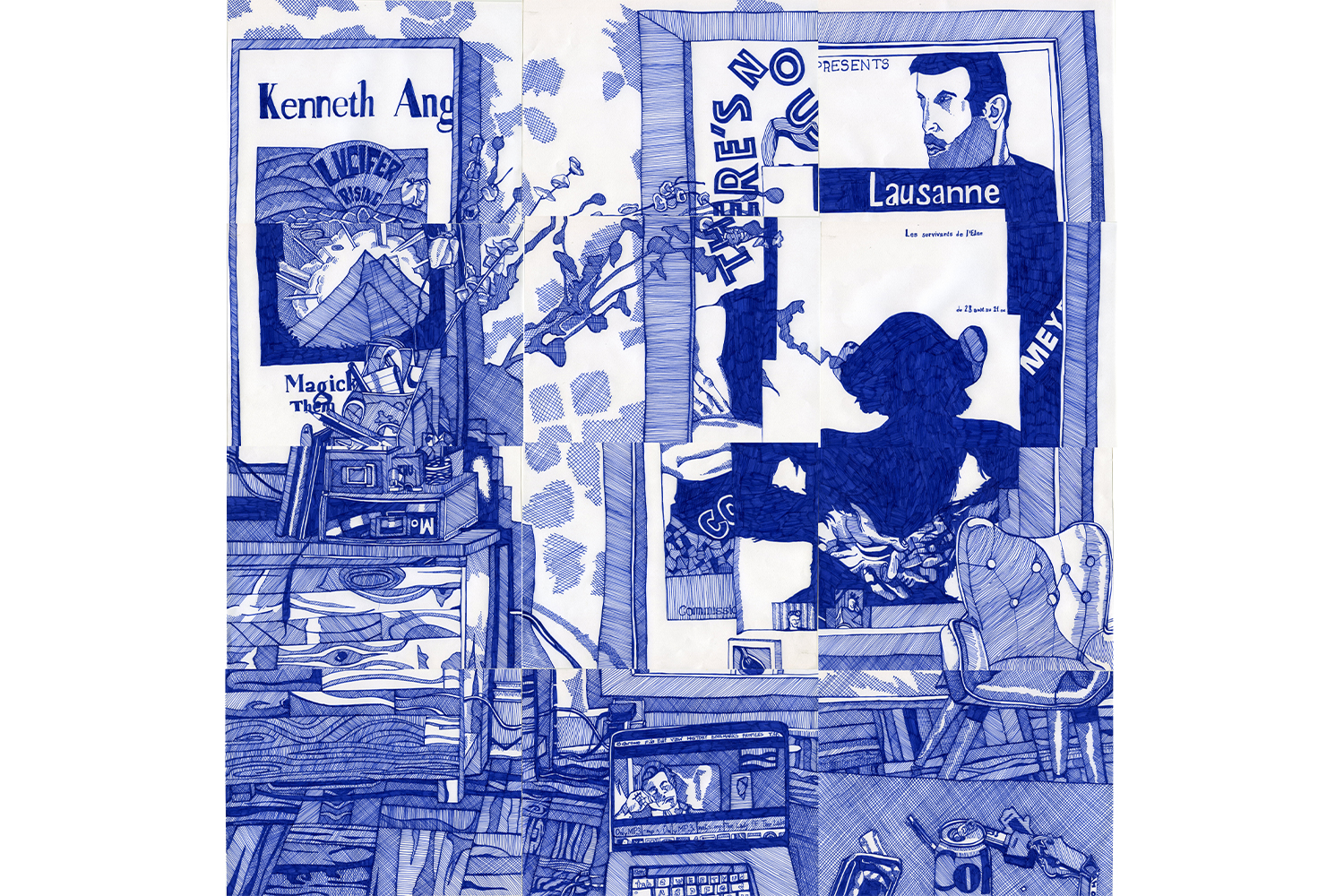

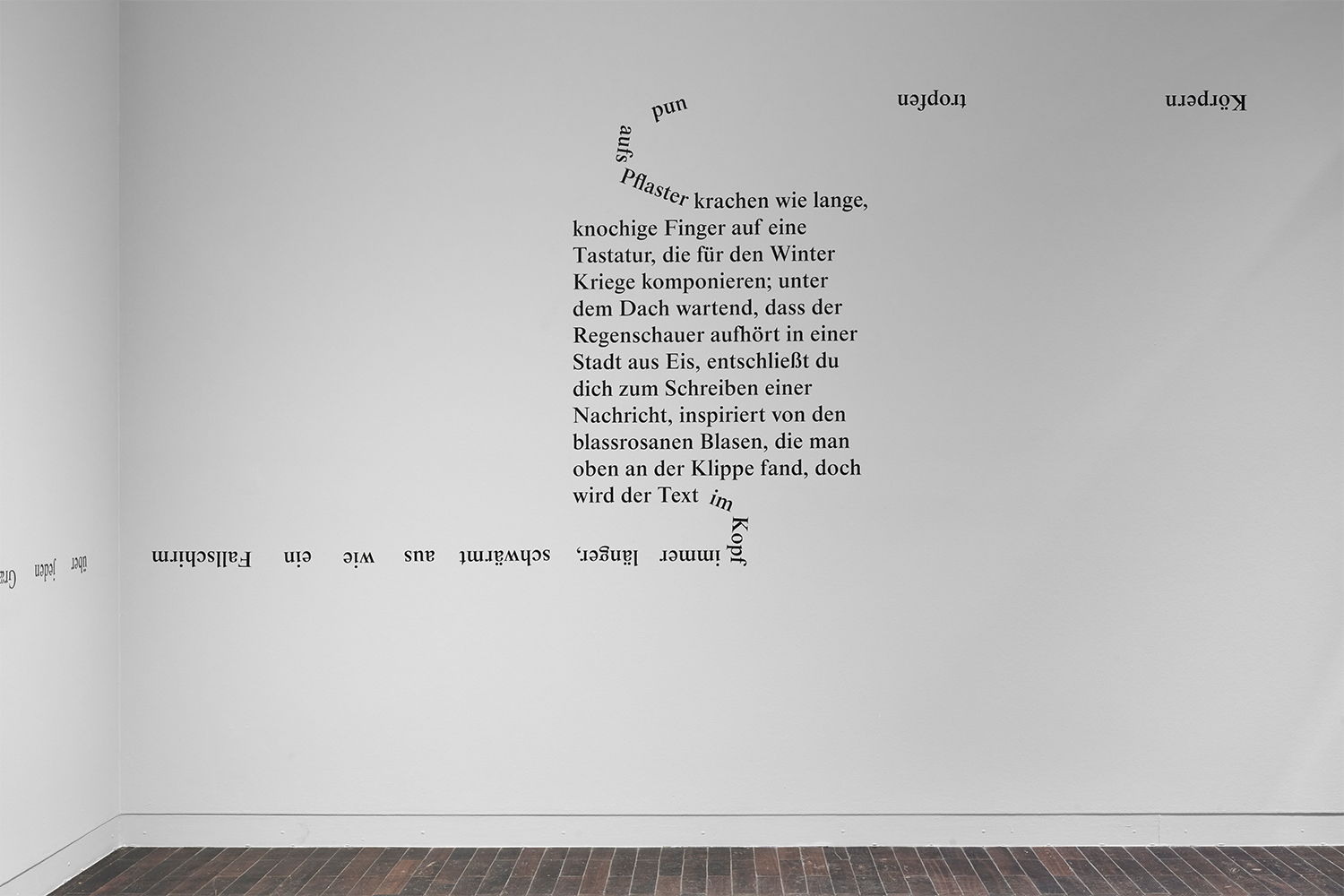

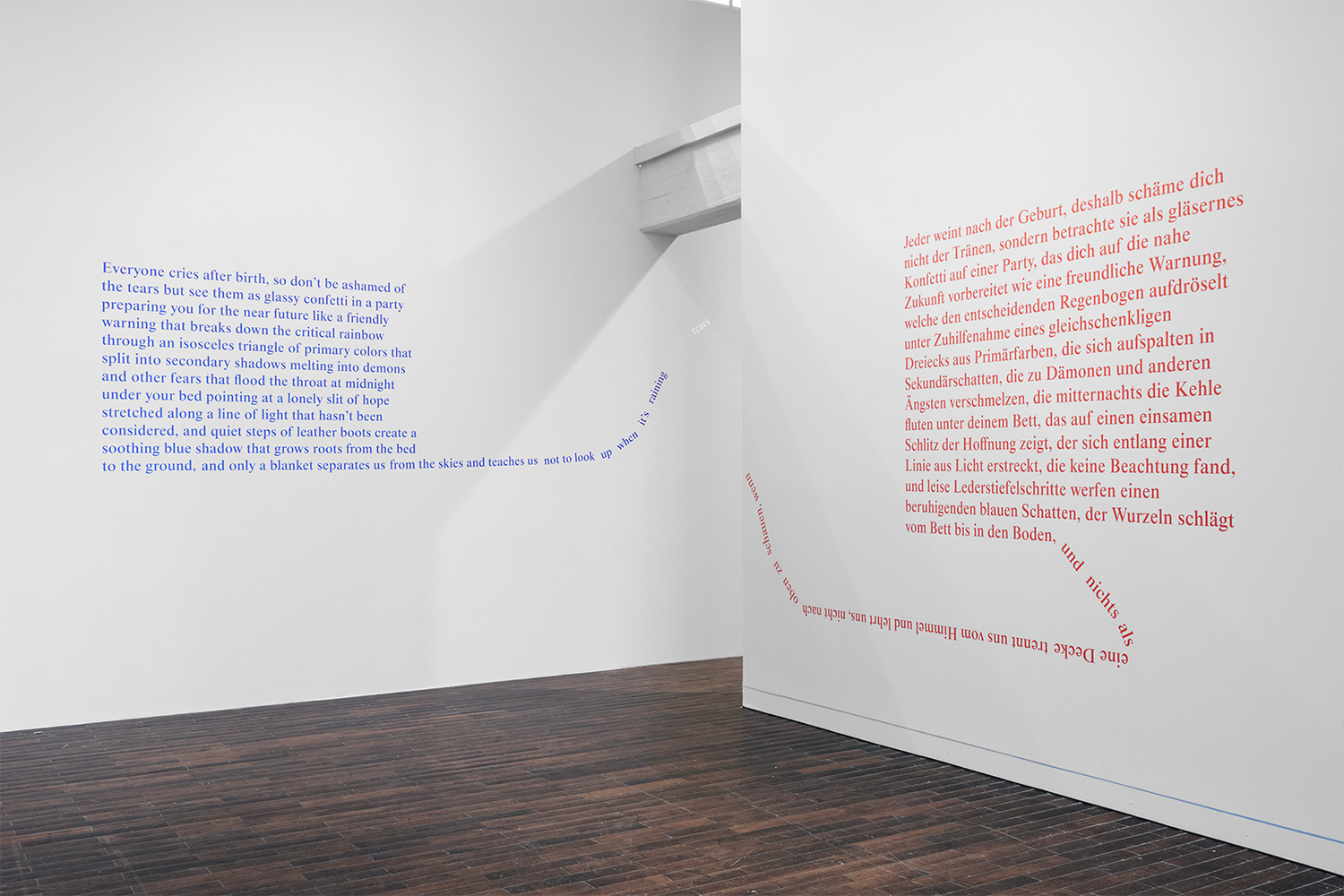

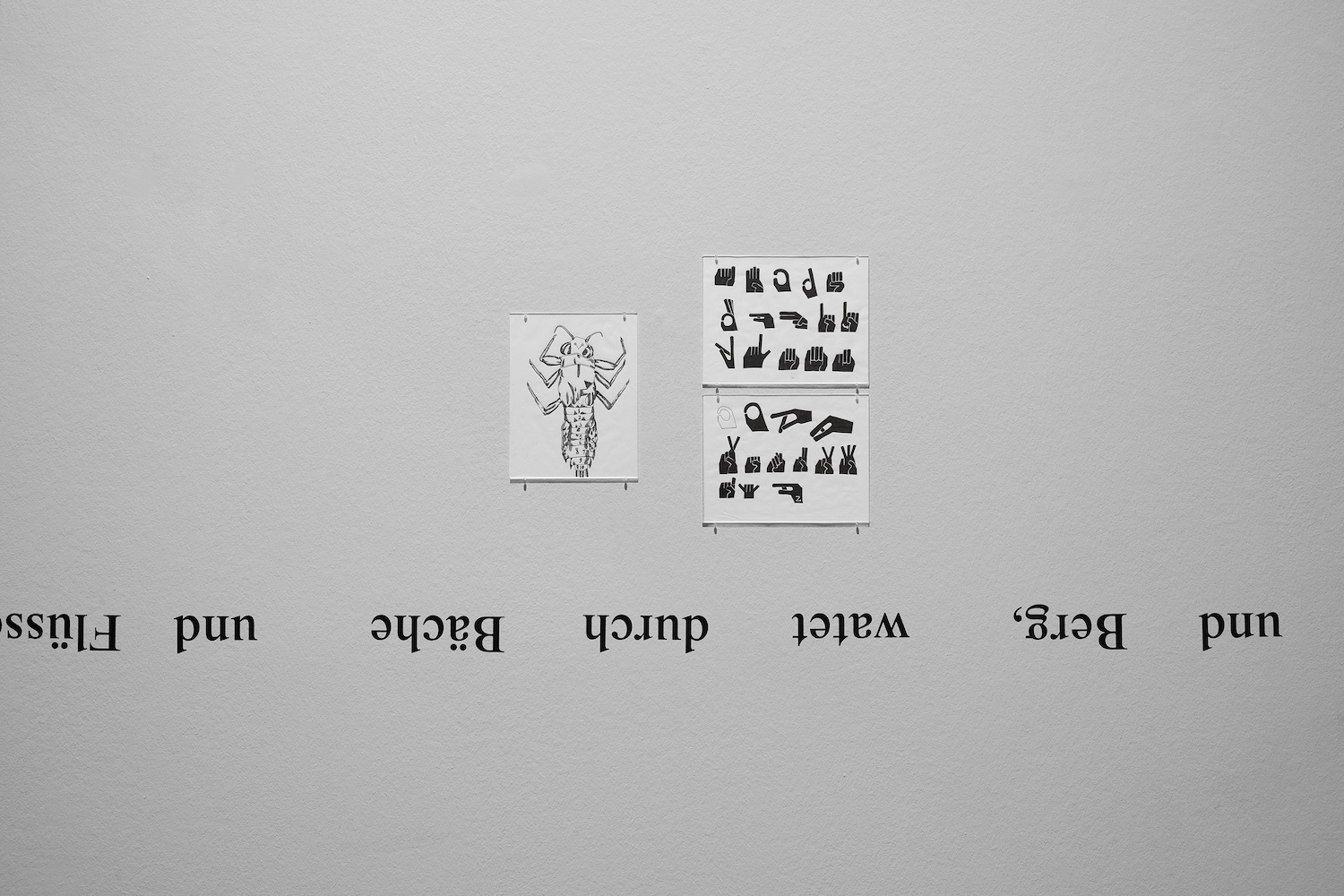

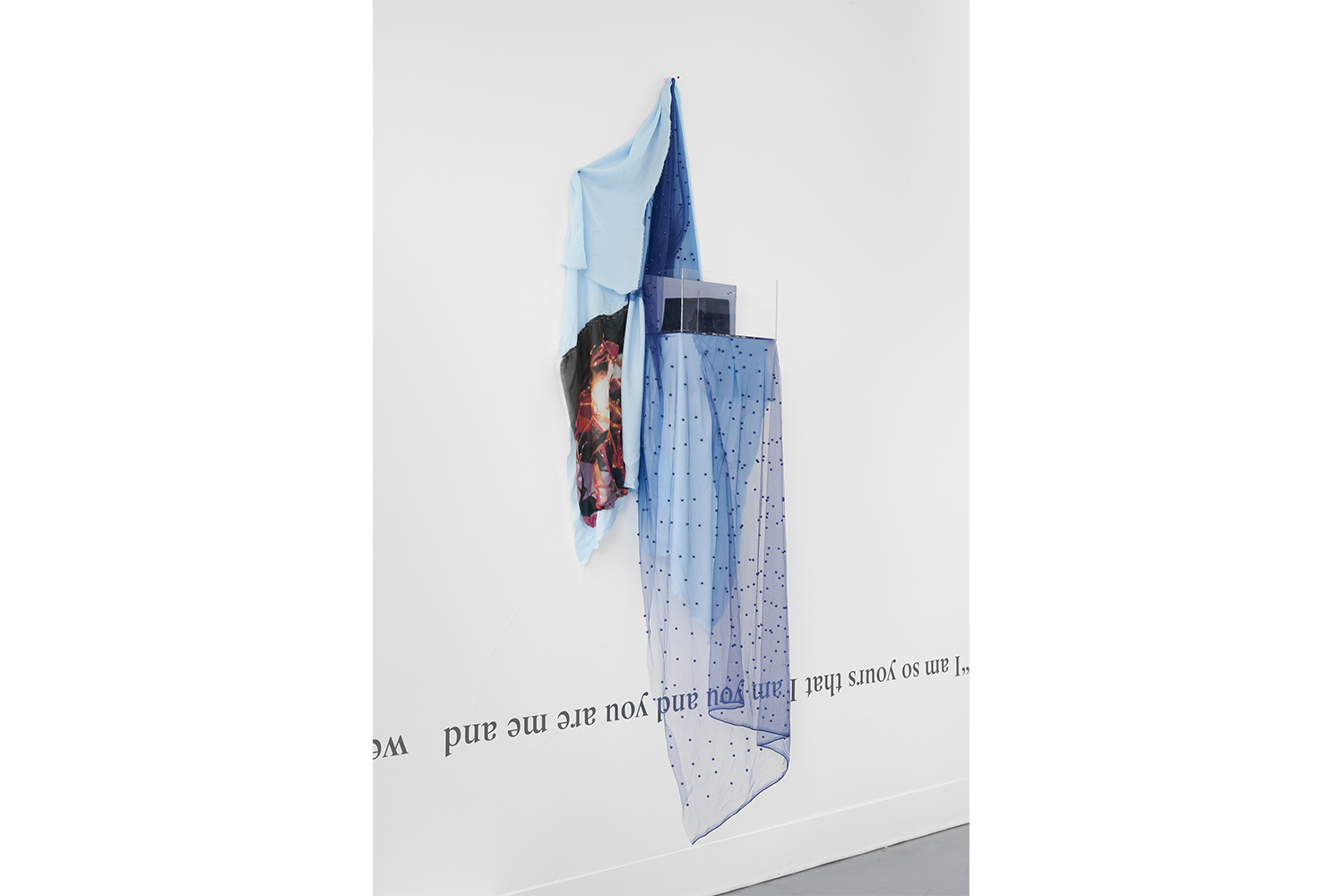

The sense of layered narrative extends even further to the show as a whole. What leads or pulls the viewer through the extensive three-floor exhibition is a text, a kind of story that runs in wavy lines of vinyl letters across walls and floors. It consists of meandering thoughts, poetic descriptions, emotional outpourings and observations, all in seemingly unending sentences. The text does contain punctuation, but it avoids full stops. Holding on to this textual thread is like holding on to a treacherous handrail; it meanders through the exhibition, from birth (“Everyone cries after birth, so don’t be ashamed of the tears”) to… not death, but instead a suggestion of intimacy, or a romantic love scene with a Leonard Cohen accompaniment on the beach (The Ocean, 2014). Despite the seeming linearity of the words, it is nearly impossible to follow the guiding story while walking through the exhibition space. But maybe it’s not that important. The text introduces a strand of equally emotive and absurdist literary discourse to the presentation, like a written voice-over for a physically absent character. Visually, however, the story achieves its aim, pulling together works from nearly two decades: several groups of drawings of cash, of an interior with a Kenneth Anger poster (Lucifer Rising), dramatic sculptural collaborations with John Roebas, a whole “Museum of Photography” (2013, a collection of Cytter’s Polaroids), and the Mai Thai University (2010), the artist’s forty-eight-hour performative academy of poetry.

A special place in my heart is reserved for Tina Fenomena – for kids (2011). Blatantly riffing on cute internet cat content, the artist shows us home videos of her kitten mewling around the apartment, going nuts over a moving red laser dot or a dangling string, fascinatedly observing goldfish in an aquarium. Quickly things get analytical and not very childlike: “Tina’s imagination is a symptom of her boredom,” we are informed via overlaid text. The cat’s having been spayed is revealed in song: “Tina, you’re no longer a woman.” A woman? Some words simply don’t behave. Does a little misbehaving already make them bad?