Upon moving from nihilist Moscow to law-abiding Berlin amid the fourth wave of coronavirus, I felt that Germany’s strict hygiene regulations had finally, in the name of protestant scarcity, drained away all conviviality associated with art openings. This feeling was poignantly captured by Cyprien Gaillard’s Polaroid series titled “Green Vessel Study,” which can be seen as part of the current exhibition at the Boros Collection. Single-serving Jägermeister bottles left around shops and documented by the artist are a testament to the only joy left during lockdown. The return of Gallery Weekend Berlin in a new post-COVID reality was supposed to remedy the situation. However, this three-day-long marathon of schmoozing, networking, and collector-artist speed dating happened to take place against the backdrop of a full-scale war less than 1,500 kilometers away, accompanied by a looming nuclear threat.

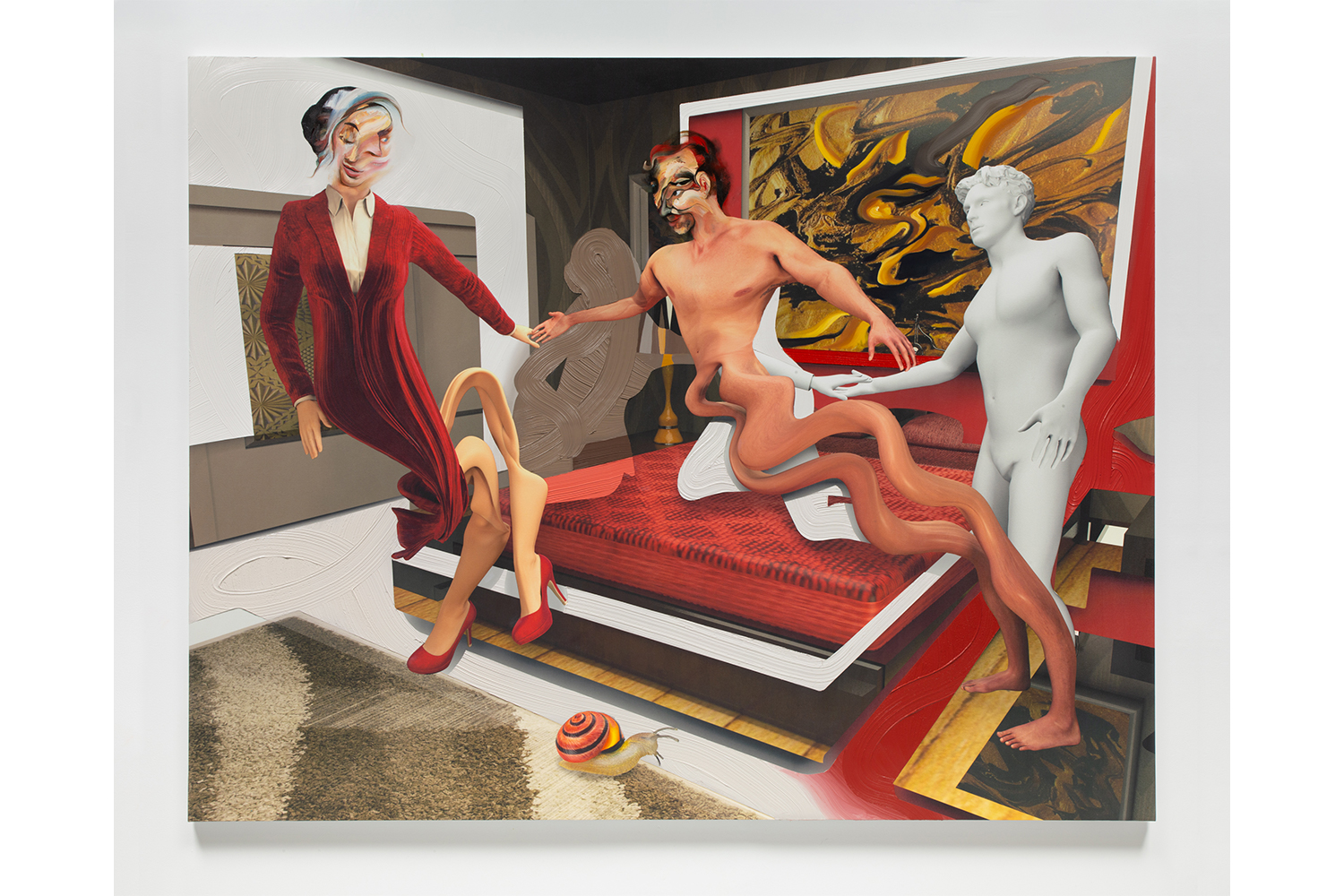

Only a few of the artworks were not silent about the current military escalations. For instance, Sterling Ruby, alongside his large-scale fabric series “Quilts,” also designed yellow-and-blue posters that completely blocked the storefront of Sprüth Magers, perhaps reminding passersby in Mitte of the utility of bomb-proof shelters. Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova, invited by König Galerie, transformed real stones into burgers or sliced them as if they were loaves of bread. Displayed on sometimes-embroidered white cloth within a brutalist defunt church, they evoke a train of associations: is the flesh of the messiah ossified and not transfigured? Does hospitality become its opposite for unwelcome visitors? Finally, Russia-born and New York–based Sanya Kantarovsky presented at Capitain Petzel freshly painted canvases that appeal to the vulnerability of the human body vis-à-vis the military-industrial complex. “The yoke of this power has always been the curse of my country of birth,” commented the artist in an apologetic tone.

The accelerated transition of our motherland into in Orwellian totalitarian state reached the pinnacle of absurdity when an anti-war activist was accused of discrediting the Russian military because he handed out free copies of the novel 1984. In her commission Bitte Lachen (Please Cry, 2022), Barbara Kruger quotes this very dystopian classic to comment on the current embrace of fascism globally: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.” Visitors found themselves complicit with this future described by George Orwell, literally stepping on his text printed on the floor of the freshly renovated Neue Nationalgalerie. Meanwhile Hamlet Lavastida, a participant in the upcoming Documenta 15, addresses totalitarian tendencies in his own country. His solo exhibition “Two Two Three Nine” at Crone consists mostly of abstract geometric decorative paper cutouts that are in fact aerial views of Cuban penal facilities. However, his critique, comprised of manifestos, slogans, and animations in which Fidel Castro is compared to Joseph Stalin, seems to be as straightforward as the very propaganda he would supposedly debunk.

Wars unleashed by states that suppress freedom of speech seem to inspire grandiose misinformation and the industrial production of fakes. David Claerbout’s two-part exhibition “Hemispheres” at Esther Schipper problematizes the relationship between an original event and its mediated representation. What seems to be 1920s amateur documentary footage of pauperized children is in fact a blockbuster reconstruction that required some fifty cameras and twenty-four singers (The Close, 2022). Aircraft (F.A.L.) (2015–21), a video of a giant airplane circumambulated by a security guard, is in fact a 3-D emulation combined with chroma-key footage shot in an empty factory hall.

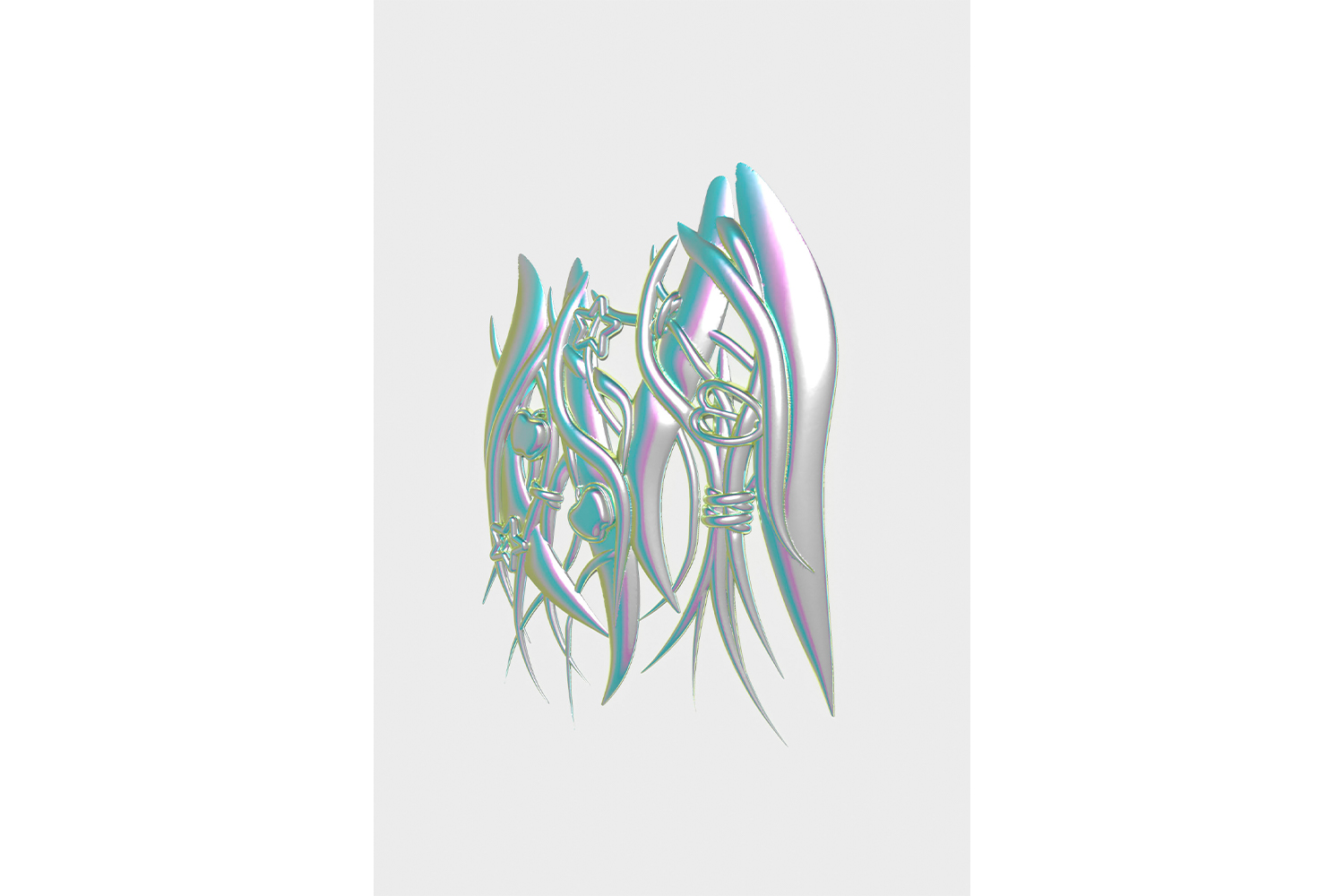

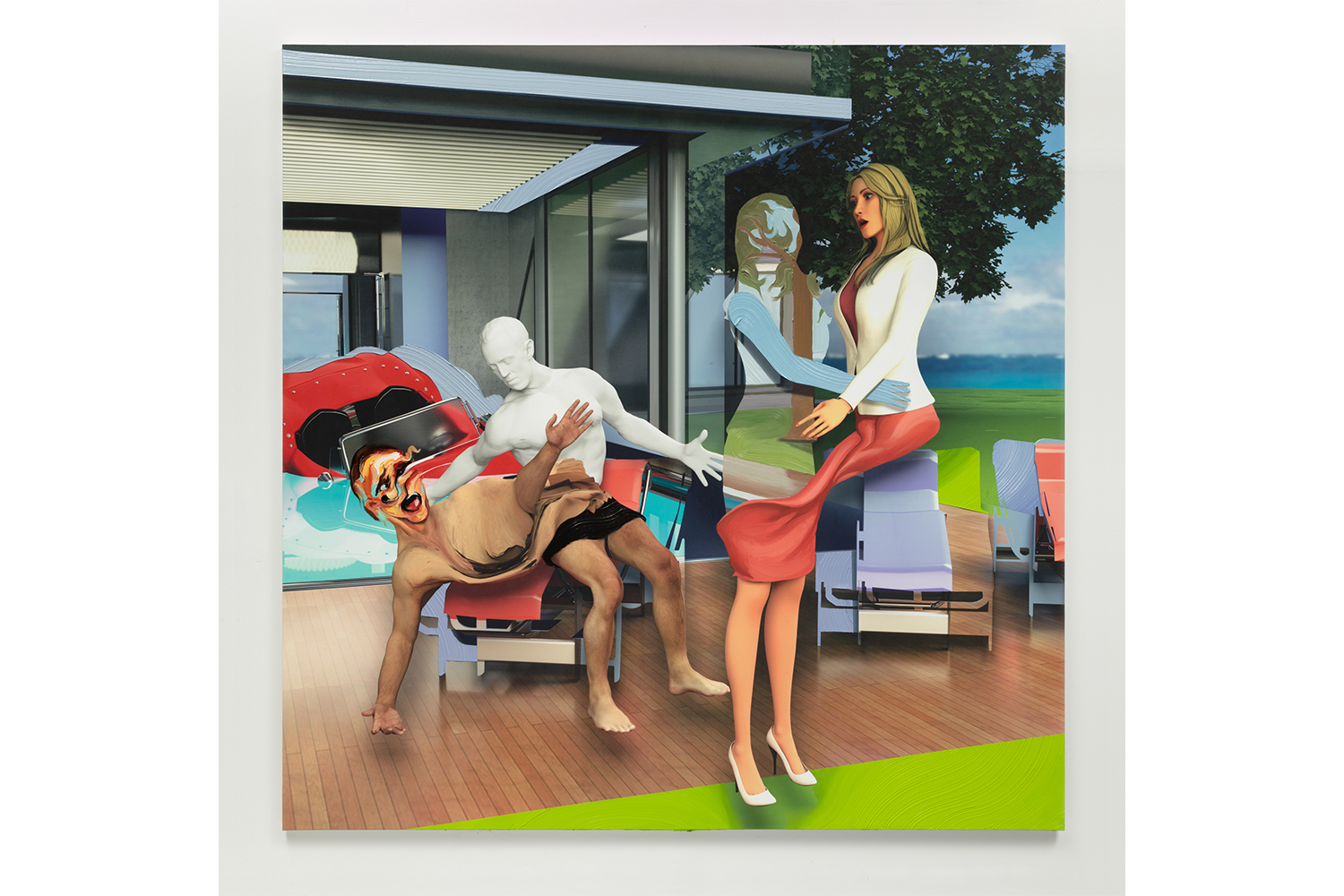

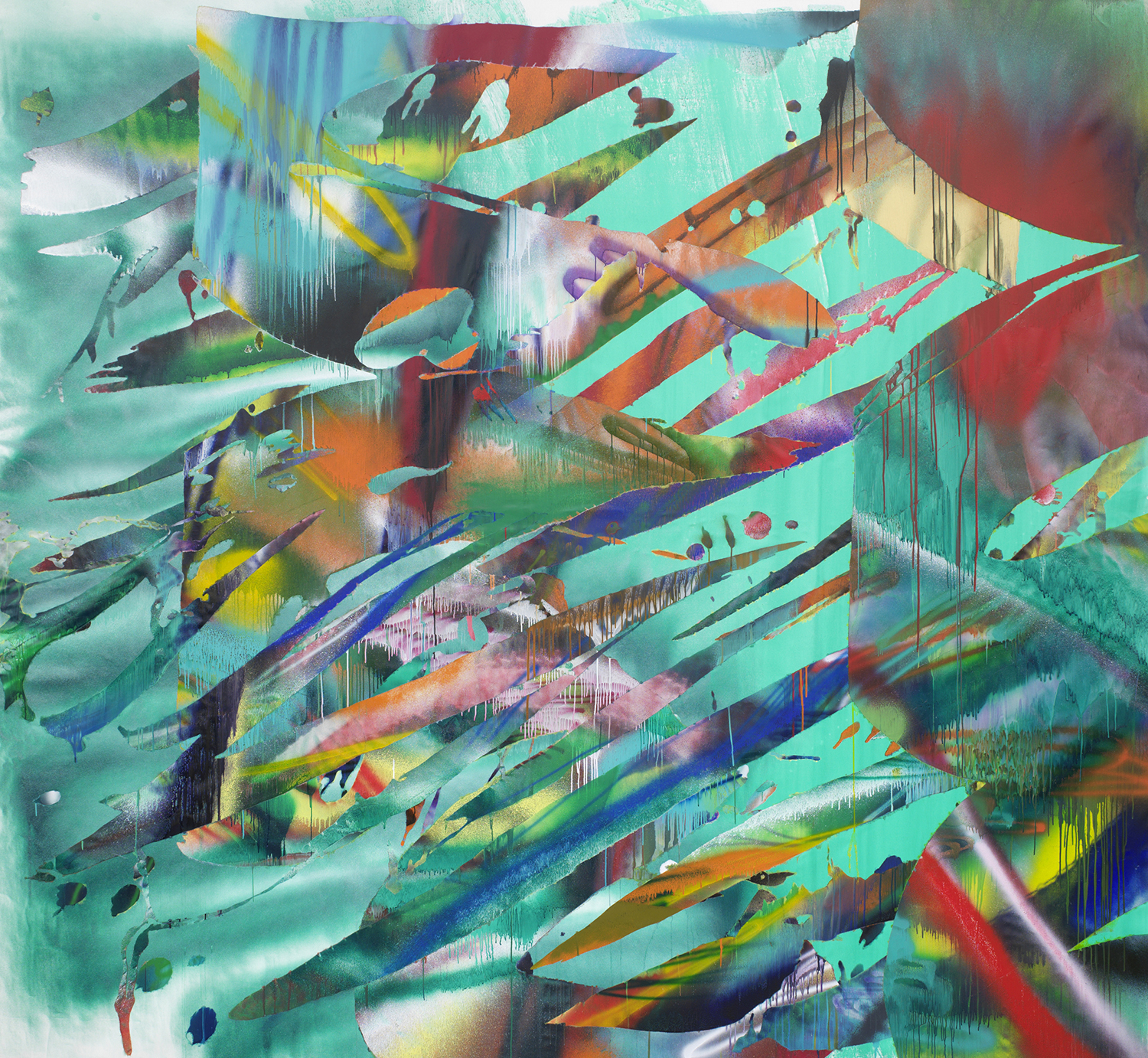

Pieter Schoolwerth pushes the manipulability of the image to a hyper-mediated extreme in “Rigged” at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler. For example, his painting Akvadiskoteka borrows its ridiculous title from the mysterious aquatic spot in the infamous Italianate palace allegedly owned by Vladimir Putin, who himself called a YouTube investigation the property the result of “compilation” and “montage.” This is a motley double portrait that depicts a hysterical quarrel between the sculptural and the painterly, foreground and background, videogame and collage.

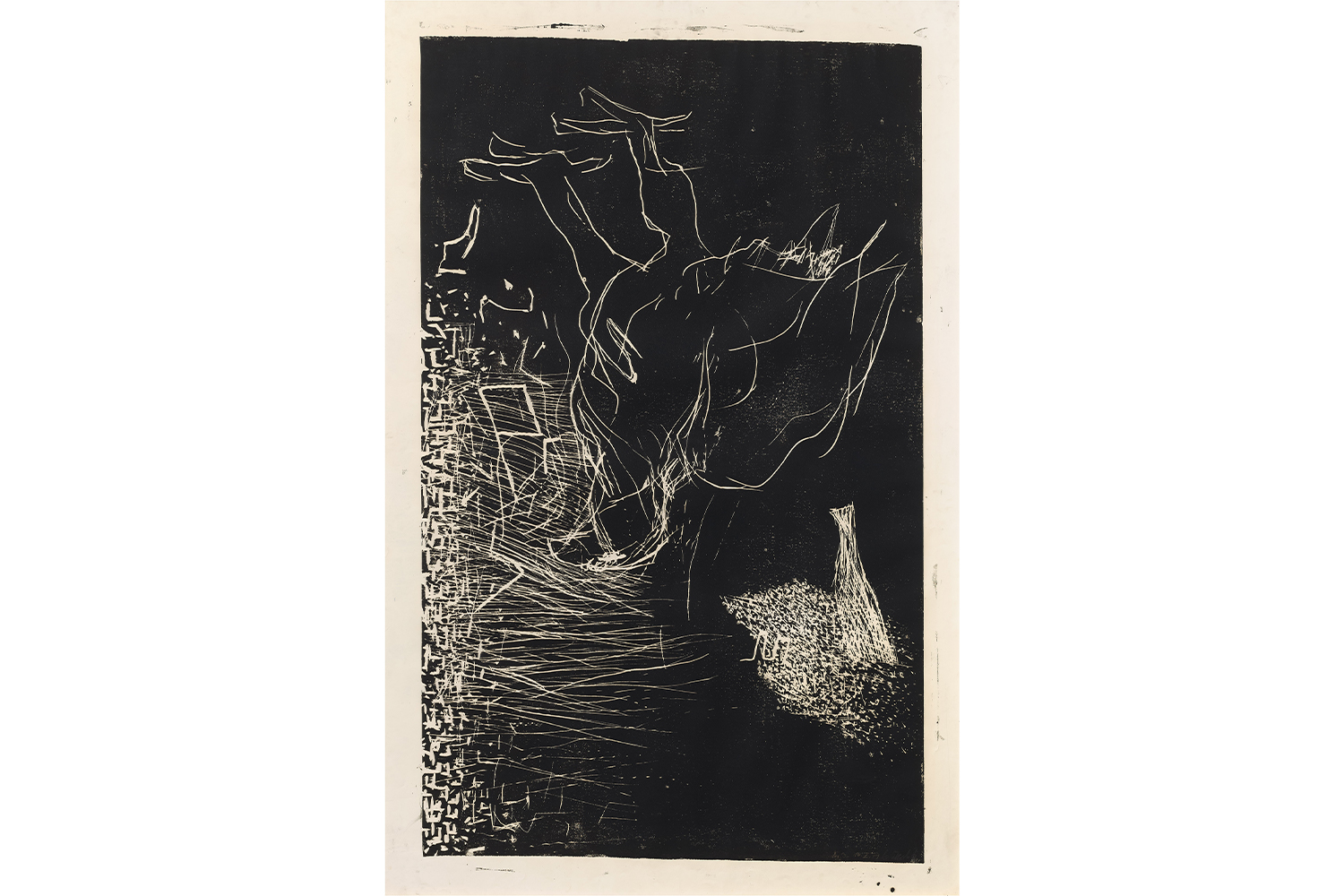

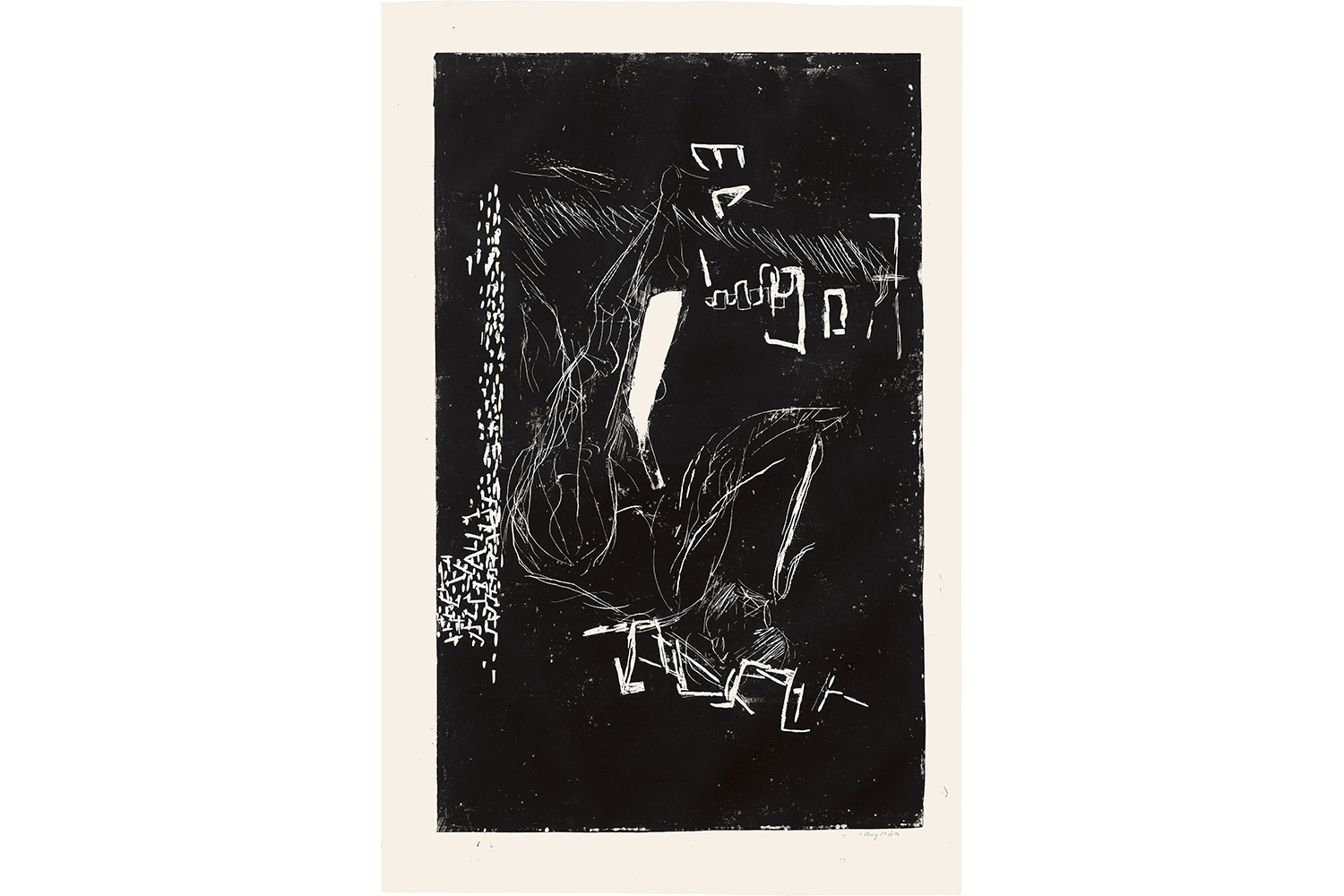

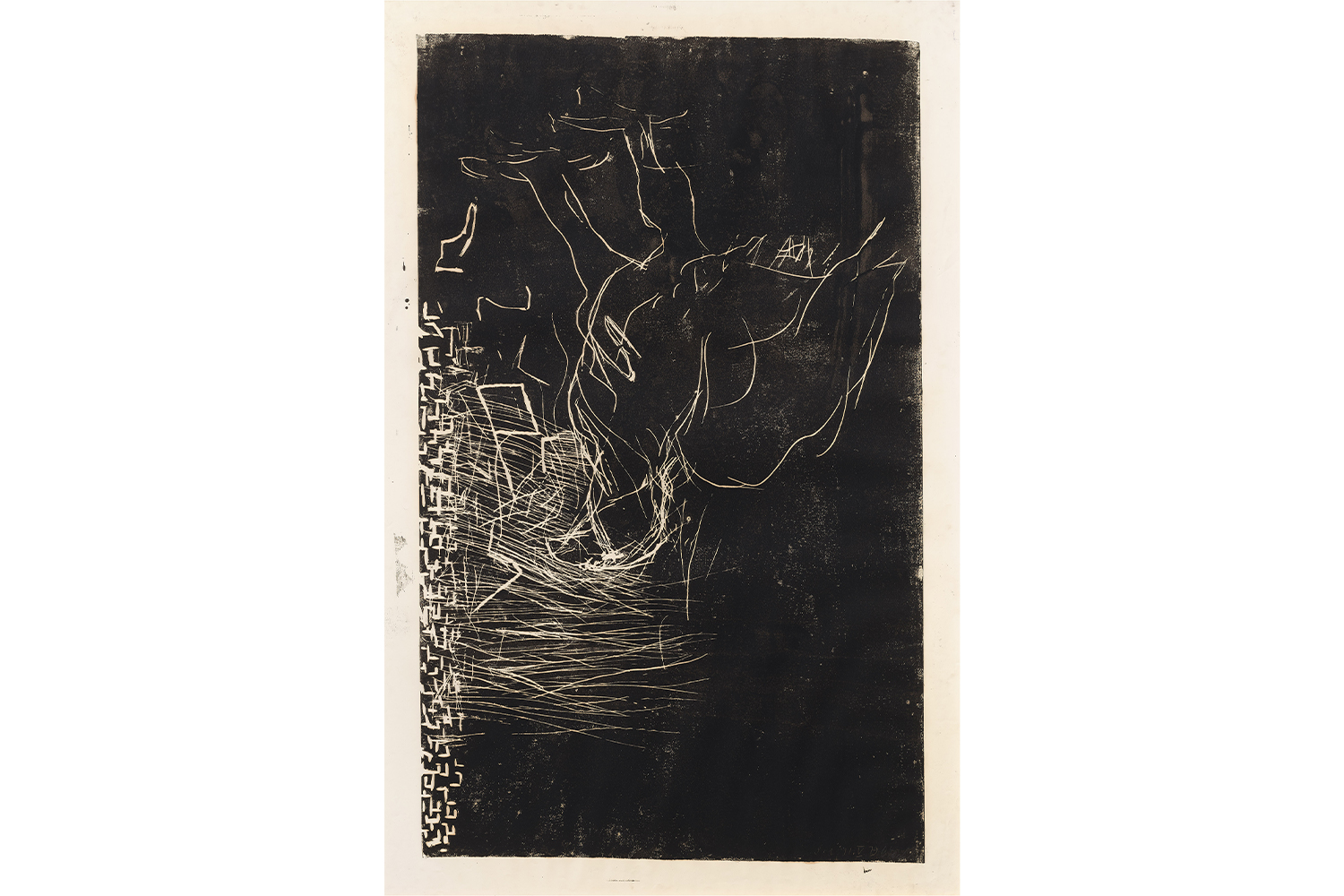

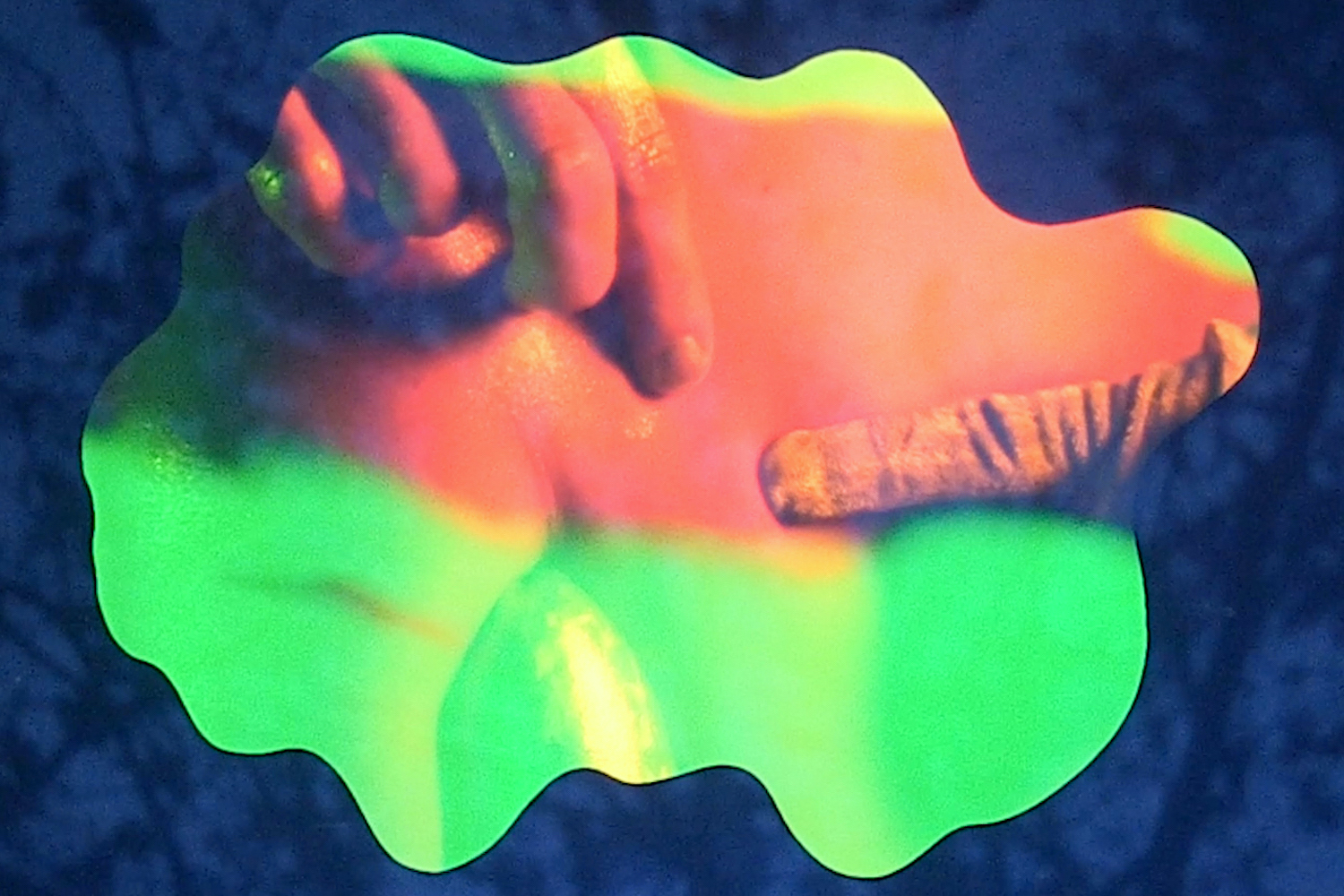

As if performing the task of mourning, some galleries mounted grim or morbid shows dominated — like “Hemispheres” — by a gray palette (or at least this is how it appeared to me in light of current events). Dirk Bells’s sculptural sound installation at BQ welcomed visitors with a distressing sense of being swallowed into a dark, vibrating abyss. Georg Baselitz’s black abstract linocuts at Galerie Michael Werner are a testament to violent exertions on paper. At Galerie Buchholz, Trisha Donnelly presents a photographic series that evokes Rorschach tests captured by photofluorography. A black-stained, almost-burned wooden parquet floor under one’s feet creates a disturbing effect, making these symmetrical fragments of landscape seem all the more like mushroom clouds from history textbooks. KINDL presents an altogether uncanny installation called “Fair Time” by Alexandra Bircken. Suspended from the high ceiling or lying on the concrete floor are deflated black rubber human figures. Given the images of torture and suffering that have spread around the world over the last couple of months, this exhibition, which was already installed in September of last year, seems ominously prophetic.