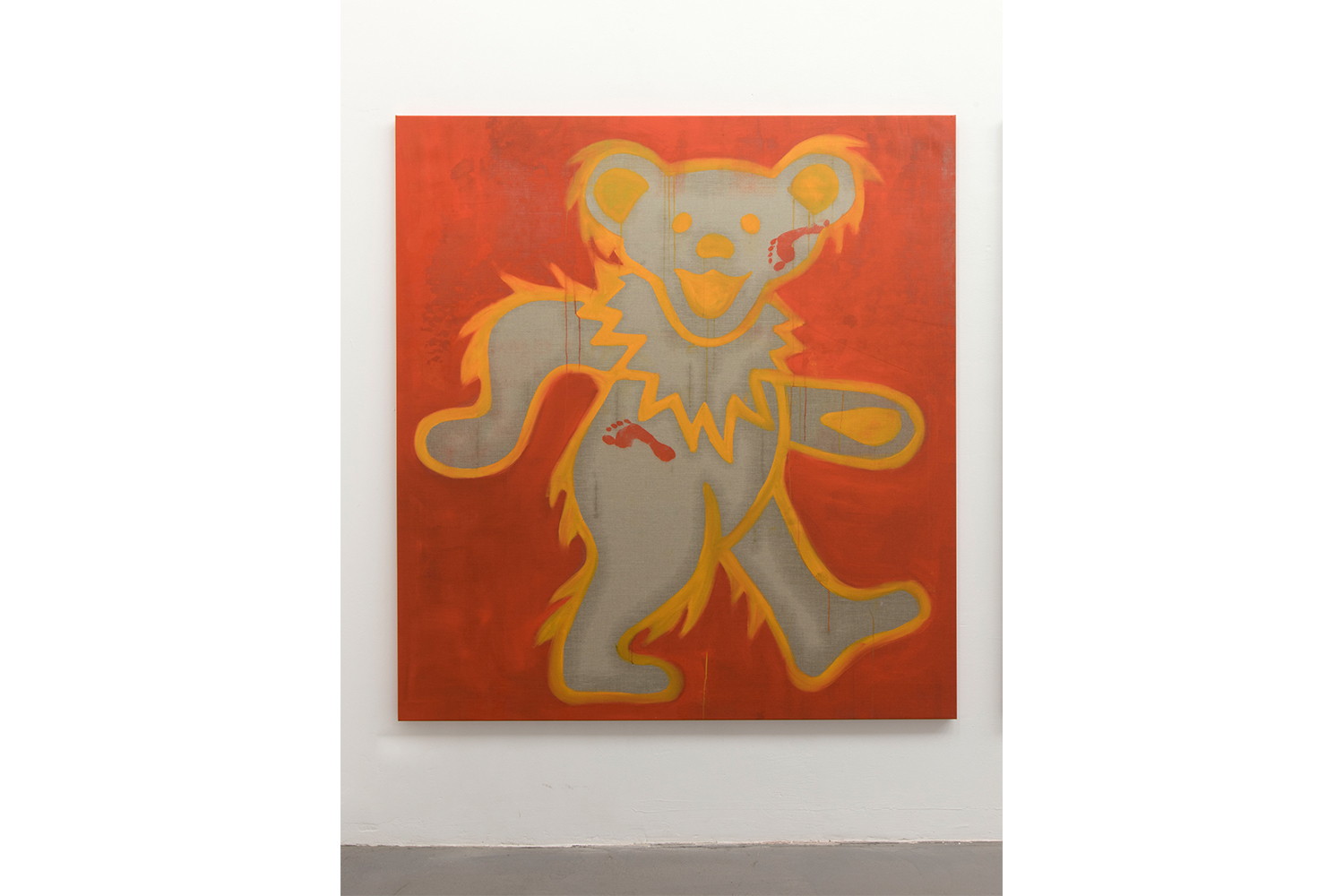

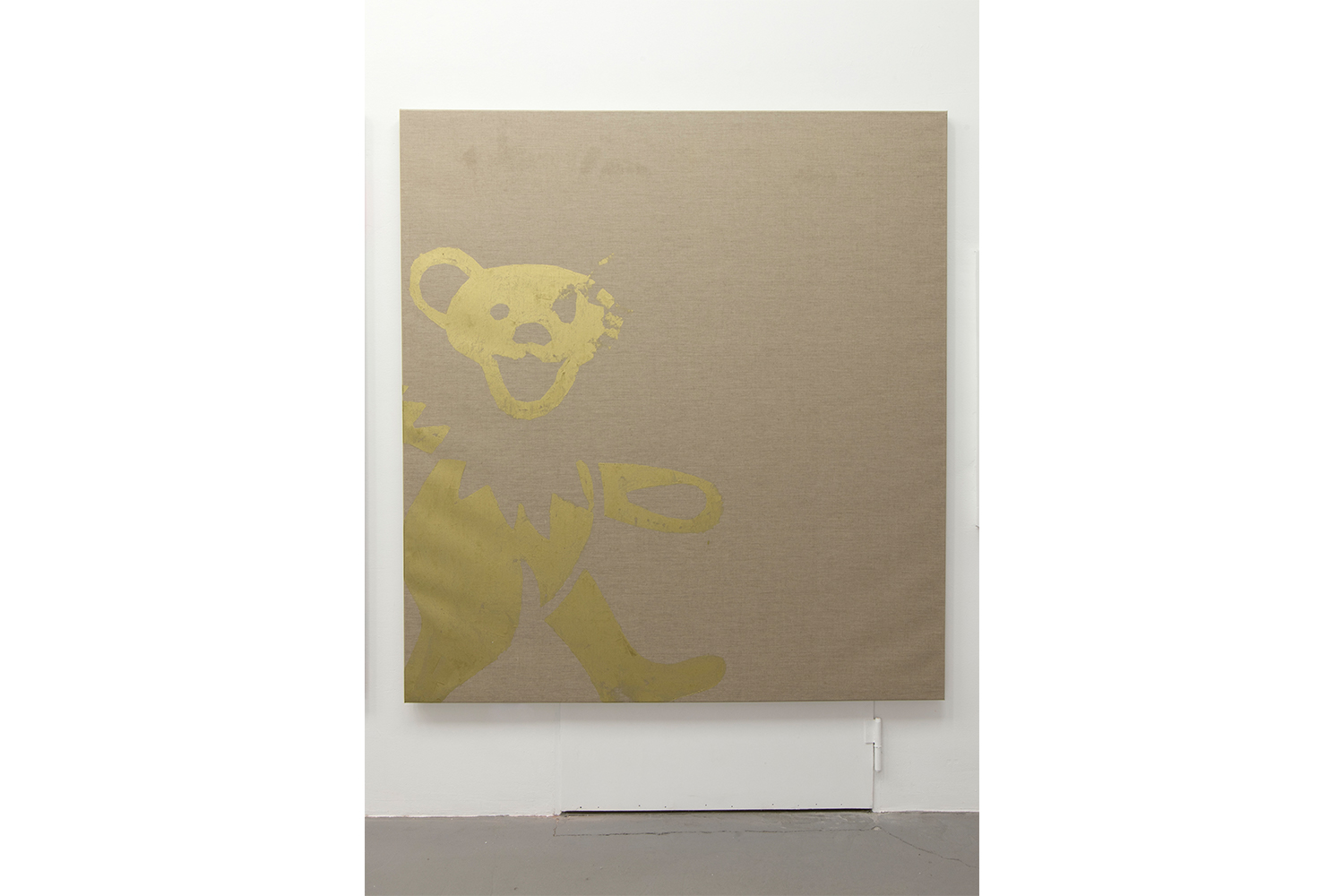

Imagine a group of dancing bears. Their mighty limbs positioned in similar poses on each frame, their jaws locked in a childish grin. They are not bears; teddy bears more like—this is not a place to fear. Imagine if it were a single teddy bear instead, marching from canvas to canvas. Each new incarnation changes it a bit—here, it is a feeble, golden shadow; there, a clownish hippie. Here, the pink contours that demarcate it are shaky; there, we find it deformed beyond recognition, like an inflatable creature in the grip of some invisible force. But, let’s face the truth, they’re not even teddy bears; it’s just oil paint clotted on canvas. Artist Tina Braegger began using the marching bears as her only subject in 2016. Consequently, the boundaries between subject and canvas started to feel less firm—being a given, the bear mutates and balances its weight in the economy of the painting, oscillating between back and center stage. It is always there, in one form or another, and it defines the way painting reinvents it, reacts against it, ignores it, or digests it. It is a logo, a mannerism, a trigger, and a grid. Braegger appropriated it from the “Deadhead” subculture (hardcore fans of the Californian psychedelic band The Grateful Dead): it first appeared in the artwork of the 1973 LP History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear’s Choice). They were designed for and inspired by Owsley “Bear” Stanley, the band’s sound engineer and one of the first and most prominent manufacturers of LSD, therefore one of the most vital drug-culture players of the American 1960s. The bear soon became a signifier and a discreet allusion to signal adherence—or support—for a lifestyle centered on rock music, mind-altering substance use, and sexual promiscuity. Hence, it began to spread in bootleg versions made by fans themselves. It started to replicate indefinitely in an untraceable historical pile of permutations.

In the very same years, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, technological advancement in the field of photocopying detonated the Japanese doujinshi phenomenon, which found its central consecration in the organization of the first convention entirely devoted to it in 1975, the Comiket in Tokyo. Doujinshi is a form of amateur self-publishing based on alternative retellings of popular narratives, especially manga. The prominent cultural critic Hiroki Azuma posits this moment as the birth of what he calls “database consumption”: all cultural products are interchangeable entry points to a narrative. There are no “primary” and “ancillary” products anymore. Pokémon are Pokémon, whether in cards, video games, anime, apps, or merchandise. The database consumers, moreover, do not merely ingest “minor” narratives but take them apart into constitutive elements, categorizing and registering them into a database to bring their object of affection together again in endless variations to be collected and modified further, such as in the case of fan art. The abolition of hierarchies between canonical and derivative and the focus on a hyper-specific (even if arbitrary) subject multiplied, reengineered, and disfigured seems to resonate with the group of marching bears surrounding us here in Essen. Thus, they seem to conform to the discourses about the exhaustion of grand narratives in painting, sitting on postmodern considerations, followed by exciting explorations in repetition, rejection of the idea of authenticity (among others), and methodologies of expanding the possibilities of producing painting clots on canvas. The circle of bears tightens. They have nothing to say to us regarding these matters; they watch us smilingly as we wander around the room, looking for the right spot to gaze back at them, mimicking the exactness of their trajectory.