The allegorical Danse Macabre from the Middle Ages expresses Death’s equalizing power over humanity: in the end, everyone has to join him in his dance. The video and sound work “Macabre,” by contrast, presents Death as an almost introverted figure, reclining on his back, absorbed in a soliloquy. He muses about loneliness and fatality, but seems equally conversant in current Netflix programming and what is trending in social media.

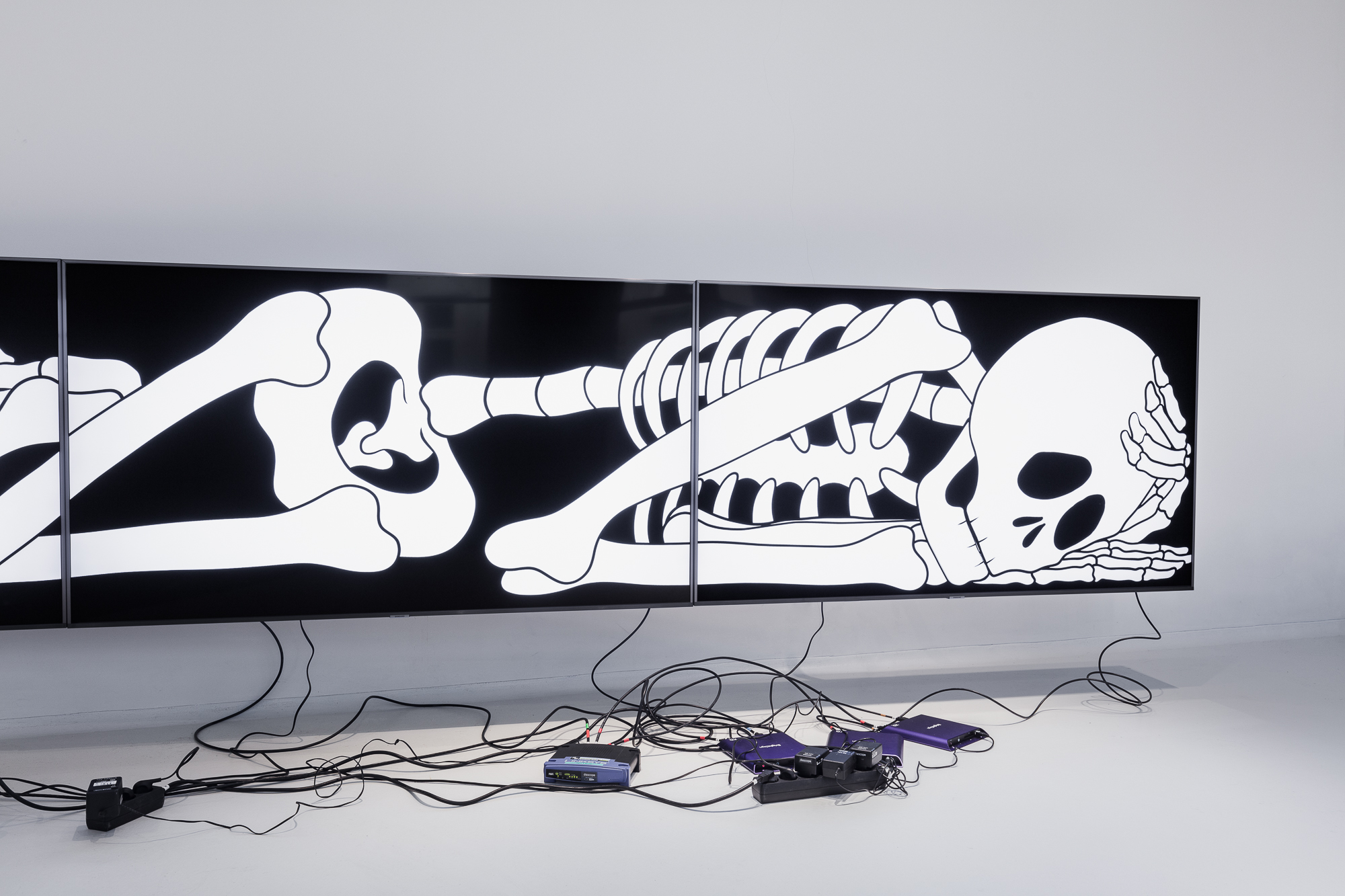

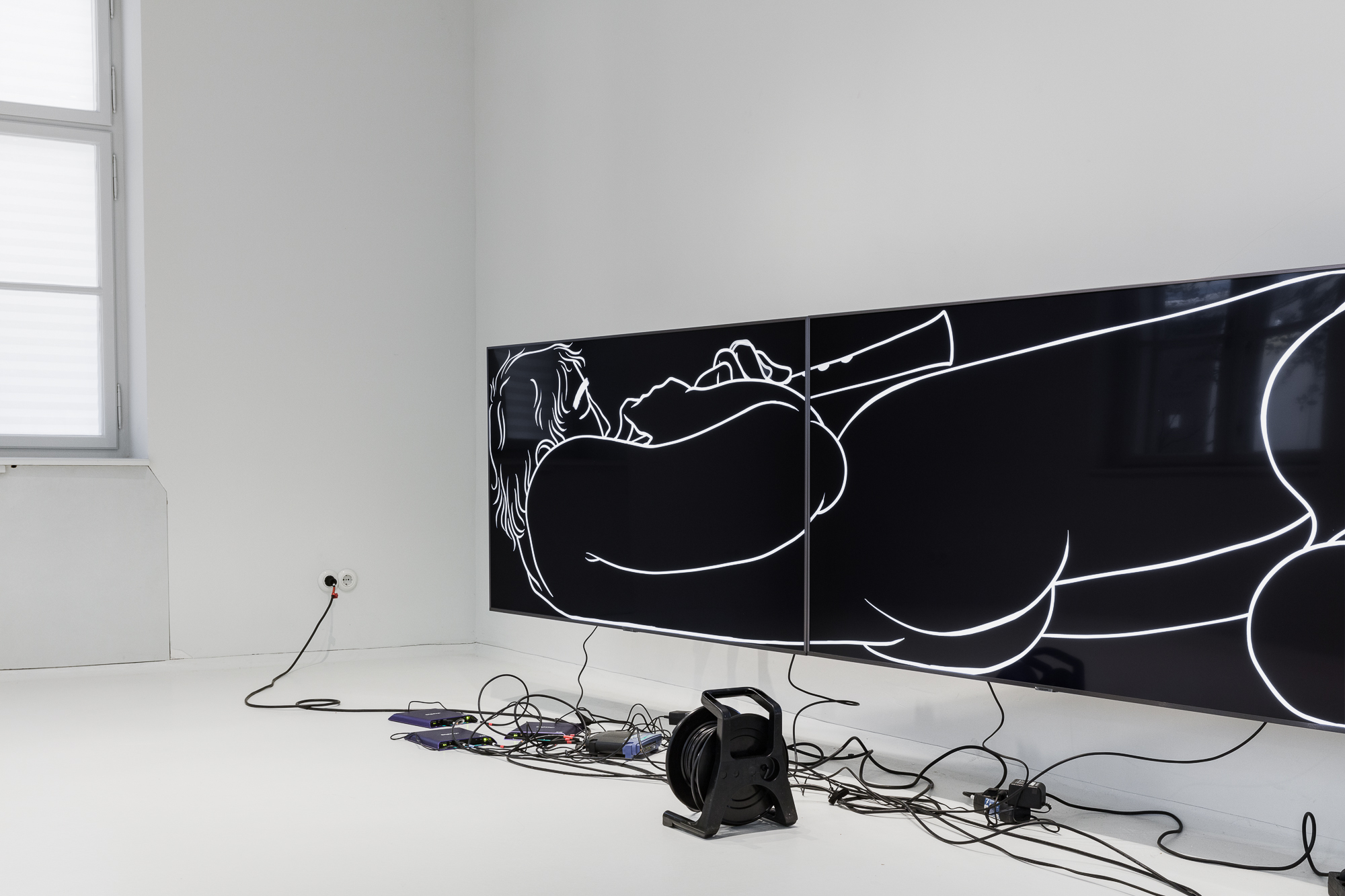

The multi-screen installation by Turkish artist Özgür Kar — known for his spare, animated depictions of male bodies in black and white — comments on both the global pandemic and its acceleration of social isolation. Marking the inaugural exhibition of Vienna’s new Kunstverein Gartenhaus, the artist conceived his impressive work especially for the art space, with its focus on film, performance, sound, and new writing. Kar’s elegantly sketched Grim Reaper longs for diversion and someone with whom to share what he reads, hears, and watches online. At least he has a digital companion: a naked young man with a clarinet who responds to his stream of consciousness with the occasional musical interlude. The half-octave he plays, also called a tritone or the “devil’s interval,” and forbidden in the ecclesiastical music of the Middle Ages, accentuates Death’s ongoing narrative and adds a welcomed pause to the flow of thoughts. Squeezed into the landscape format of huge flat-screen monitors, the skeleton and the handsome nude show little movement within the borders of their digital cages. Nonetheless, they manage to articulate a nuanced scale of emotions resembling our own attention economy, being drawn to whatever beguiles our distracted minds. Death quotes phrases from reality TV shows, YouTube clips, and seemingly familiar pop song lyrics.

Kar’s sparse aesthetic draws on late-night MTV cartoons of the early 2000s, but also on Persian and Ottoman manuscripts and the films of Lotte Reiniger, a pioneer of silhouette animation during the Weimar Republic. Another influence on Kar’s elegiac reflection on life in a time of algorithm-driven information overload is Samuel Beckett’s famous “Not I” from 1973 — a dramatic monologue in which the only thing visible to the audience is a woman’s mouth uttering deconstructed sentences at a ferocious pace. Kar’s chattering protagonist likewise mixes references from high and low culture, performing them in a broad spectrum of tonalities.

The lighting in the exhibition space is soft, and the sound equipment is prominently yet casually displayed. There is a feeling of time slowing down as the murmuring voice and musical accompaniment induce a lethargic yet pleasant feeling of being distracted from the real world. Death, the allegorical mastermind, patiently waits to conduct us into the darkness of his pixelated world. But even though Kar’s immersive scenario deeply entangles viewers in social media’s seductive power, he seems to speculate on an emancipated spectator who is able to master the work’s time-draining proposition. In the end, it is a matter of how far death, disguised as a social network bot, is allowed into one’s life.