In “The Puppet Show,” curator Mohamed Almusibli assembles seven positions by artists working across (and between) performance, sculpture, drawing, and painting, in a witty presentation of puppeteering as a contemporary critical mode beyond the ancient theatrical form. In “On Bunraku,” Susan Sontag’s quick treatise on the complex puppetry founded in Osaka, Japan, in the seventeenth century, the critic identifies the medium’s characteristic “double statement” as “hyperbole and discretion, presence and absence of the dramatic substance.”1 Such dichotomies are pried open in this technical survey, which imagines new rubrics for the manipulation of the (typically anthropomorphic) puppet by its master, and by extension questions the complications of autonomy within the theatrical illusion.

Two sculptural works by Denis Savary begin the exhibition. Villa III (2021), a miniature dollhouse modelled after a Dadaist Swiss villa, is angled so that its open façade reveals the full interior of a brightly illuminated unfurnished set. Harsh shadows exaggerate the imbalanced architectural composition of the model to uncanny effect, whereas his series of nine blown glass and copper Charm sculptures (2021) play with light to emphasize their complex geometry and craftsmanship. Around the corner, Nils Amadeus Lange’s newly commissioned installation and literal puppet show La petite mort (2022) is perhaps the show’s most sincere and candid ode to puppetry as a performative proxy: “The play is acted — that is to say, recited — that is, read.”2 Lange appropriates the aesthetics and didacticism of puppetry as a form of children’s entertainment to express a phantasy on sexuality. Two performers wearing morphsuits embody the Kleistian notion that the very inanimateness of the puppet is its precondition for expressing an ideal state of the spirit.3 As they control the objects either directly or via a system of pulleys, it is understood that the puppet “lives not as a total body, totally trembling, but as a rigid part of the actor from whom it is derived,” per Roland Barthes, also on Bunraku.4

Savery’s and Lange’s non-realism is offset by the imposition of Latefa Wirsch’s sculptures Artist Collective (2022) and Turn up the show (2021), which present anthropomorphic models (puppets) made of various relational materials including readymade costumes and furniture, satirizing the broad overlaps of the public performance of private life. (“The operators are giants, interlopers.”5) Further to this, Reba Maybury’s all-new works identify the aforementioned “double statement” of puppetry through a literalizing metaphor for the gendered dynamics of sexual labor and humiliation. Rented furniture and tableware has been arranged for sixty guests or “johns” (Table Plan Geneva, 2022). A leather clipboard, pen, and sheet of paper, Guestlist Clipboard (2022), keeps a record of the would-be attendees and their table number. The invitees’ pseudonyms that appear on this list and on the place cards at the tables (john’s name places, 2022, handwritten by a submissive client of Maybury’s) are the real anonymous usernames of johns living in Geneva. By reattributing the onus of puppetdom in the sexual transaction from the worker to the client, Maybury questions the veritability of autonomy within the capitalistic desire for payment.

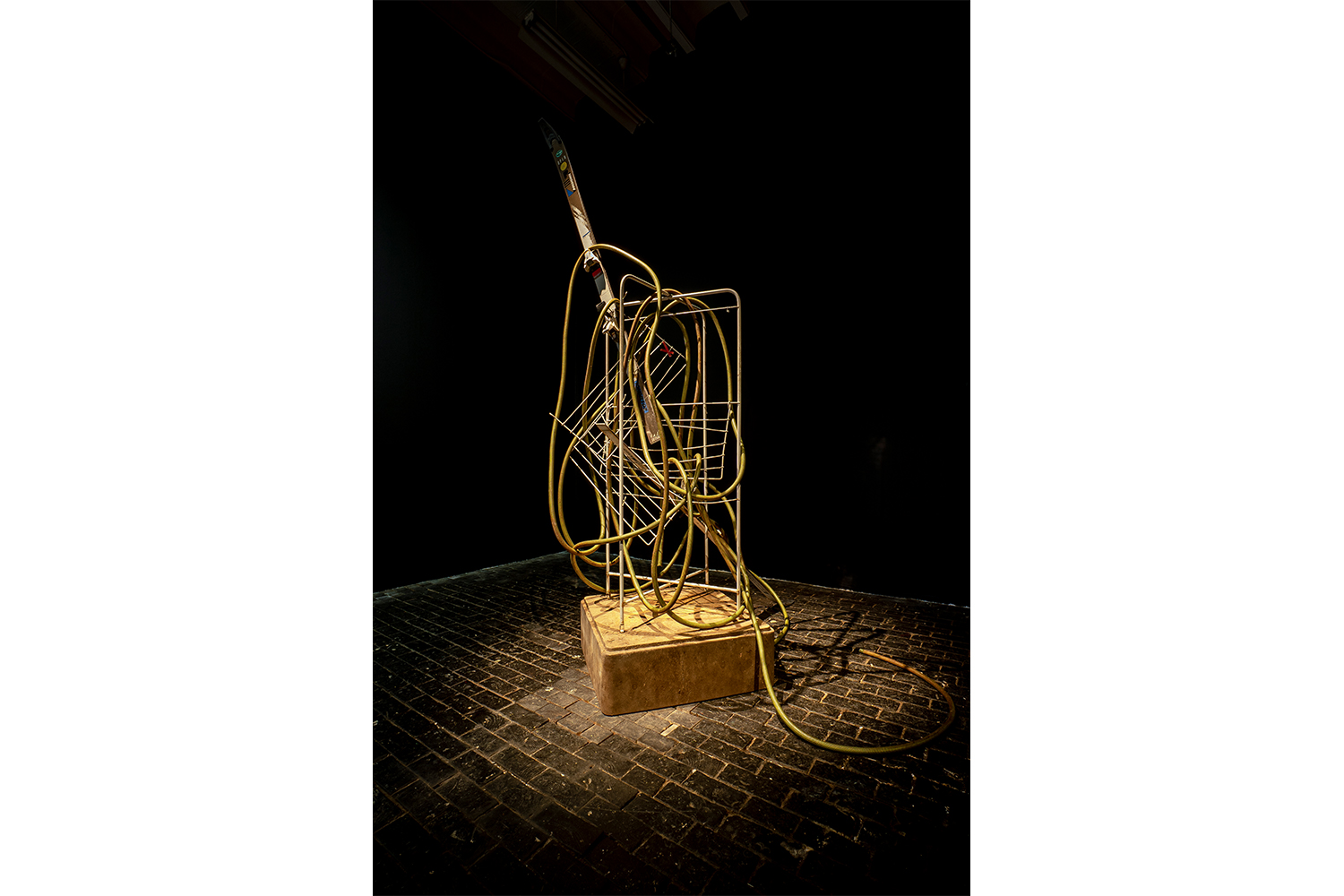

Ser Serpas’s new works — reflections forgetfulness in, never ended try not to, travails what prevents, and last stations (all 2022) — assemble discarded household and industrial materials found on the streets of Geneva in an art-historical reimagination of the archetype of a puppet as a significant object. Flanking Serpas’s sculptures, you know where you are (2022), Linda Semadeni’s triptych of gesturally applied oil, acrylic, gouache, ink, urine, and blood on linen, appears like a score for a puppeteer. On another wall, a two-panel oil and glitter painting by Jasmine Gregory, Flibbertigibbet (2022), denotes an abstractive representation of a potential object. Likewise, A Cover Letter That Says I Love You: A Performance Review (2020), showing two almost identical images of a person wearing bright clown makeup save for slight gestural discrepancies, obstructs easy interpretation of the subject as either puppet or master. Through varying points of departure, “The Puppet Show” explores the scope of Almusibli’s interest in corporeal channels of visual and performative expression, succeeding particularly through a critical dissection of the political dynamics of the puppet and puppeteer, both literally and allegorically.