This week marked the return of a live Expo Chicago, which had been on indefinite hiatus like so many other art fairs since the spread of COVID-19. The number of participating galleries was nearly the same as it was prior to the pandemic. Booths at Expo run anywhere from $9,000 to $60,000 — on the expensive side as square footage at art fairs go — so each gallery has needed to devise a strategy to recoup those expenses and still earn a profit amid a reluctant bear economy shook by our present geopolitics.

As the fair wrapped up, many of the more established gallery programs reported satisfying sales, although the same may not be the case for fledglings in the Exposure section, which was a ghost town in my passes through it. Kasmin reported a range of sales between $10,000 and $100,000 — the latter the highest sale as yet reported to the fair’s management. Chloe Waddington likewise cited strong sales across the program at Timothy Taylor. Richard Gray, Monique Meloche, and Jessica Silverman gallery staff all spoke about nice ranges of sales and pending deals.

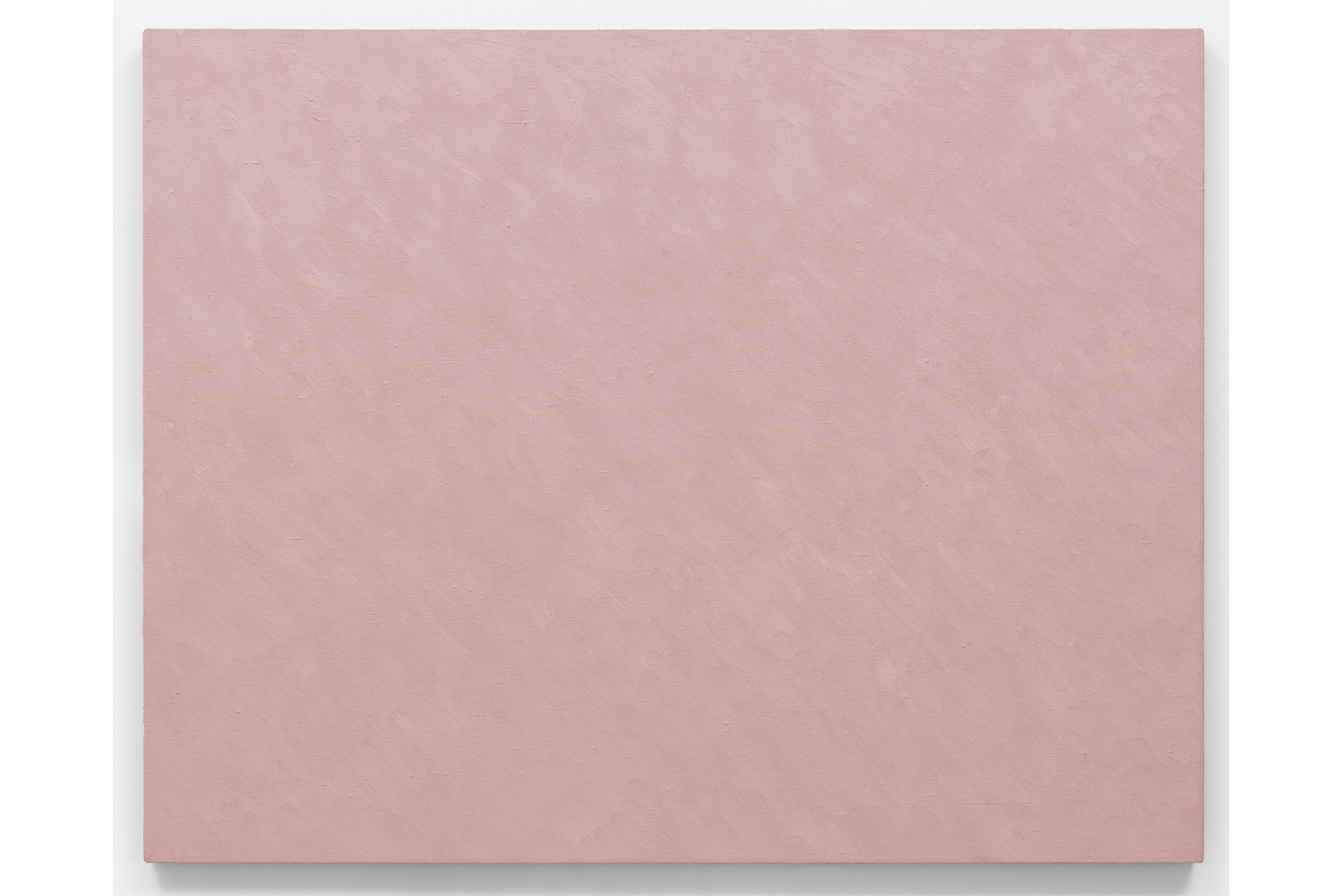

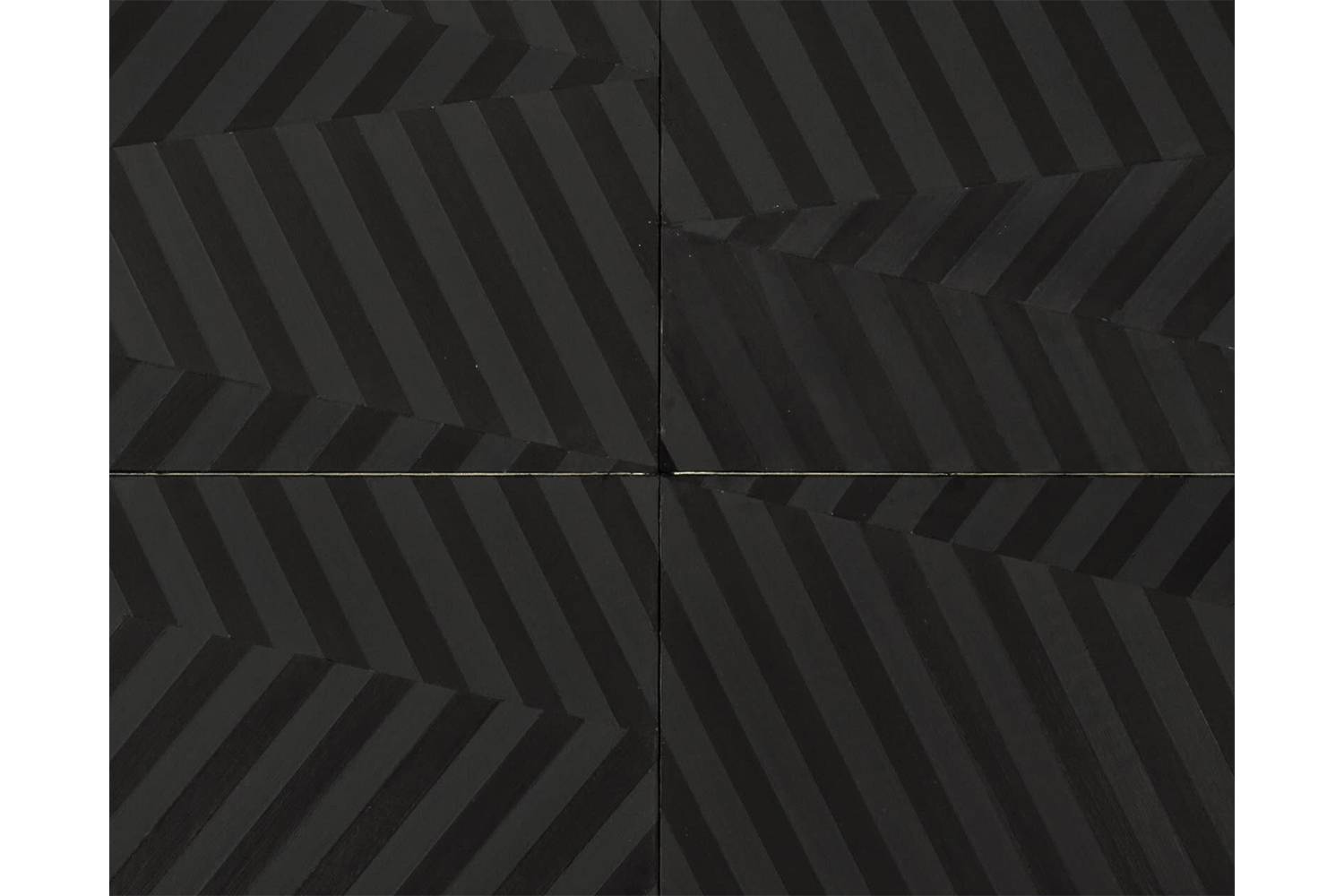

The best single work I saw on view at the fair was Marcia Hafif’s Neutral Mix Painting: April 12, 1977, Viridian, Vermilion (1977) at Fergus McCaffrey, with its plum-mauve scumbled monochrome surface, as if the rigors of Concrete art were blushing. Hafif is overdue for a renaissance among collectors and institutional exhibitions since her death in 2018. A close second at the fair was James Little’s Black Star (2015) in Kavi Gupta’s eclectic booth. While most of Expo kept to the art-fair default of myriad spectacles of surface and imagery — so much attention-grabbling razzle dazzle (a frankly repulsive volume of unselfconscious use of glitter on view) — Little’s striped black monochrome seduced with a suavely finessed, buttery oil-and-wax surface. (To my eye, Little even upstaged the similarly measured striations in a brand new, enormous Bridget Riley canvas at Max Hetzler.)

At the time of filing, both the Hafif and Little works were as yet scandalously unsold, which may be an indicator of the more or less discerning tastes of what Diane Rosenstein, of the eponymous Los Angeles gallery, described as “important visits by curators and top collectors.”

The best single artwork I saw in Chicago this week not at the fair was Hanne Darboven’s Ein Jahr: 1970 (2007), a perfectly stunning installation of forty-two silk-screen prints on view at Devening Projects alongside engrossing painterly constructions by Sean Sullivan. I bring up these favorites in order to profess my biases — my own inclinations for what artistic tactics are the most exciting orientations toward possible futures. Grids and monochromes, cerebral and formal materialities — these works belong to an art that externalizes the body politic from the picture plane, charging as “figures” the audiences and social actors around which these works circulate.

Certainly many other substantive art experiences were on view at Expo, but the fair was noticeably overburdened by every sort of gallery trying to capitalize on current figuration trends: so many bodies were depicted in every fashion, but most veered into uncomfortable, accidental kitsch. One of the rare exceptions was Vielmetter’s pairing of My Barbarian’s haunting, literary masks — a couple of which adorn the ornamental specter Standelabra 4 (Cassandra as Judith) — with sweeping new erotic photographs by Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Taken together, these works suggest an approach to gender, race, and sex as open questions rather than the fixed, overdetermined testimonies espoused by most figurative works at the fair. The performance group My Barbarian is fresh off a recent survey at the Whitney. These latest works of Sepuya’s are reassurances against the risk of oversaturating the market with a formula of fragmented figure studies with which the photographer has become associated; still, his preoccupation with a narrow ideal for lean physiques and masculine beauty unfortunately keeps step with the most regressive and vain aspects of gay male culture.

Most striking was the booth for London’s Richard Saltoun: a thoughtfully curated installation of fiber works made by an international coterie of women artists over the past forty or so years — works that persist in the pressures they put on dichotomies like art and craft, painting and sculpture, and the effects of a binary gender projected onto even the most abstract gestures within art’s canon. To confront long-standing issues of class, labor, gender, and art-world power relations strikes me as a much more activist position than so much of the justice-oriented illustration on view throughout the event.

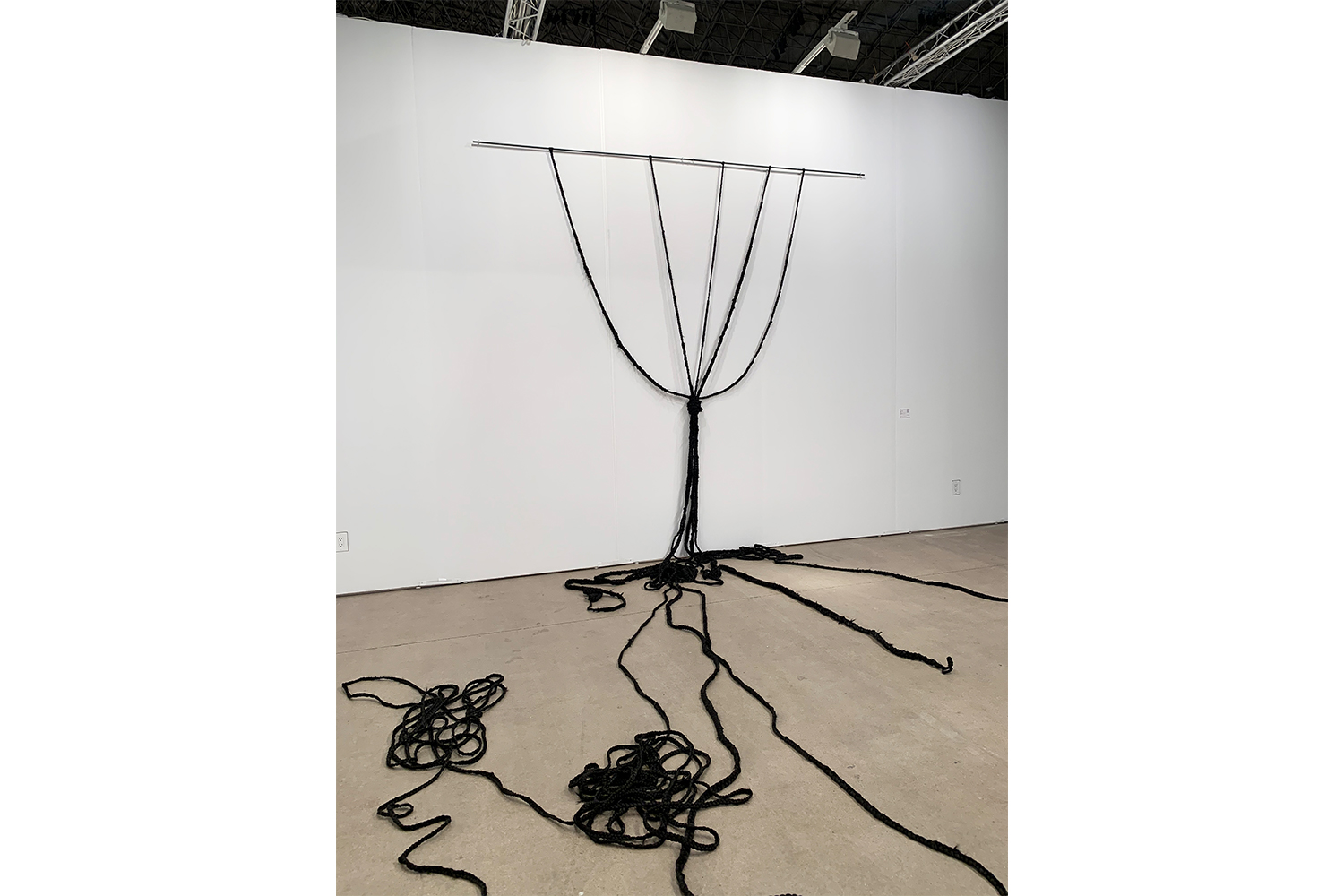

Barbara Levittoux-Świderska’s Srebrne Muszle (Silver Shells, 1985) is an intricate net-banner adorned in shining oyster shells and in adoration of some mermaid-mer(m)other, while the duo known as Telas de Amaral’s Flores #16 (Flowers #16) from the same year is a lively field of coiled tendrils in shades of red — lipstick, merlot, dead roses — that follows upon post-Minimalist impulses to suggest rather than literally depict a body.1 Echoes from these elaborately woven wall tapestries could be traced to Sandra (2022), an outstanding installation of coiling black braids by Diamond Stingily at Cabinet, and Steve Reinke’s deliciously hued “Untitled (needlepoint)” series at Foxy Production.

Dazzling presentations though there were, one withdrew from the fair struck by an underlying unevenness, as if many galleries are still trying to ascertain what it is people are seeking to buy these days. Meanwhile, Chicago’s gallery and institutional offerings around town proved to be robust reinforcement to the pell-mell of fair days.

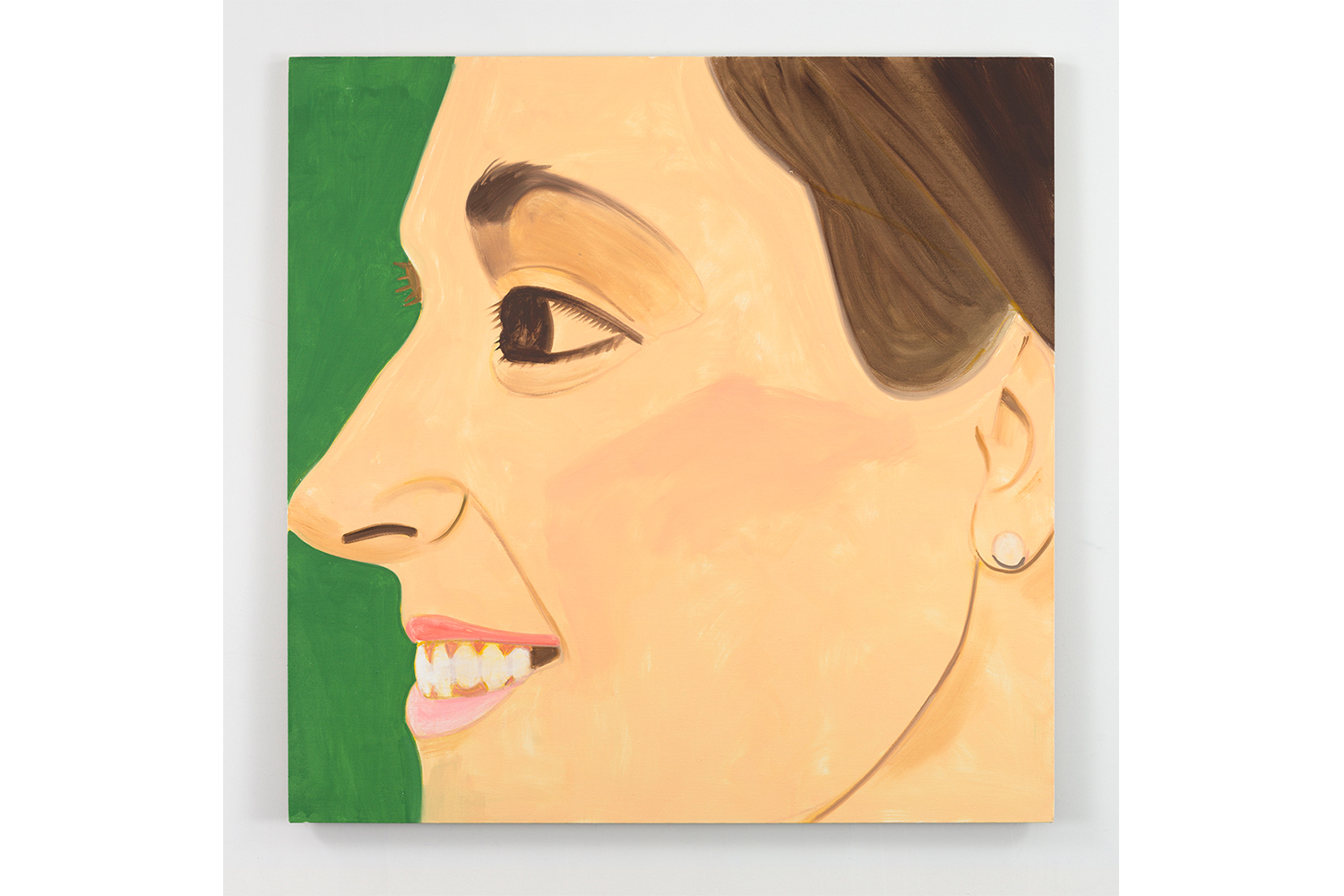

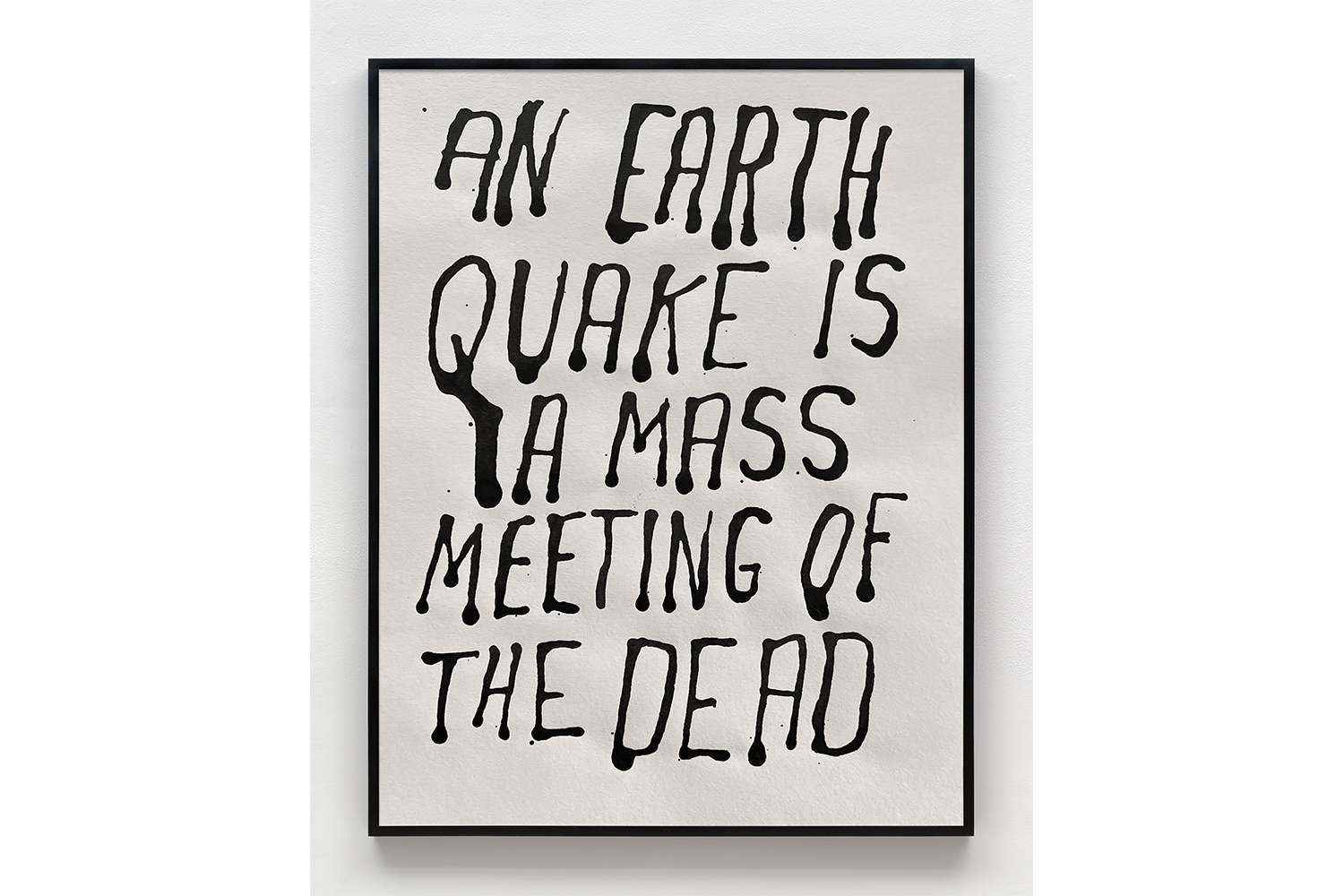

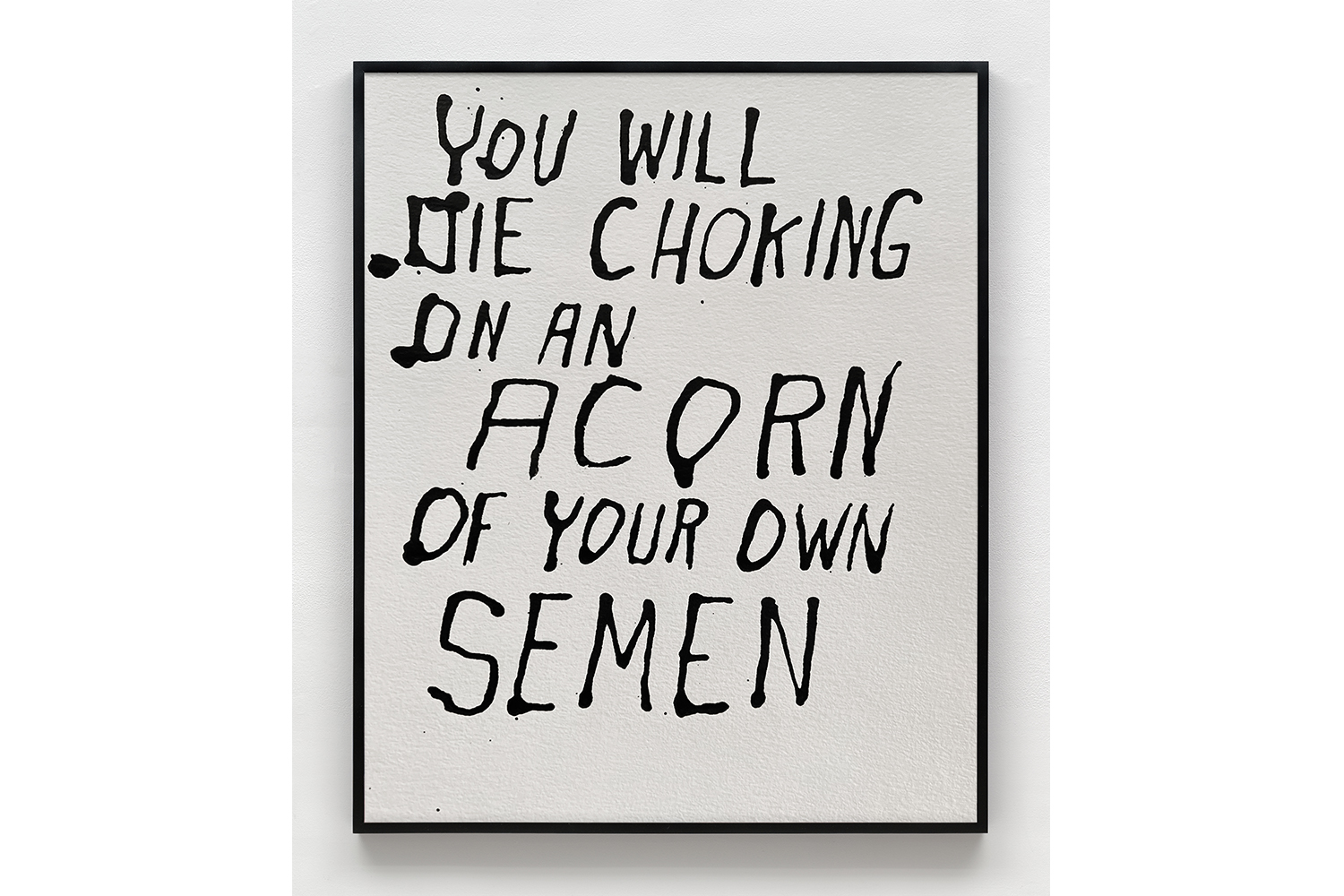

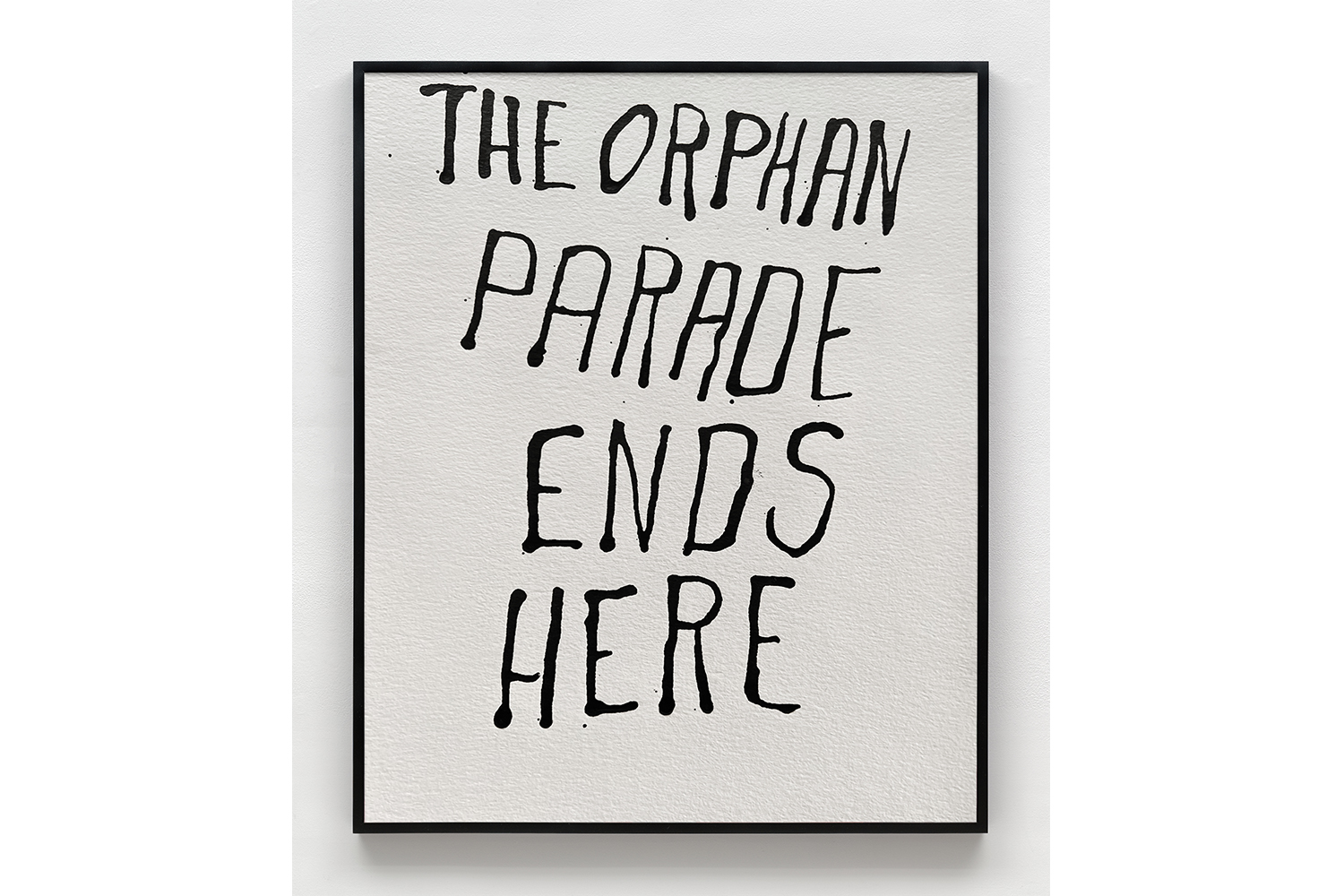

Two of Chicago’s brightest — Arnold J. Kemp and Sam Jaffe — have respectively mounted concurrent projects in the city. Kemp’s complimentary exhibitions at M. LeBlanc gallery and the Neubauer Collegium (the latter a part of the University of Chicago) consider masks as critical thresholds in navigating the regulations of identity — a compelling turn since his artwork appeared in the fictionalized Chicago art world that served as the setting for Nia DaCosta’s 2021 remake of the racially charged horror flick Candyman. While M. LeBlanc is showcasing a suite of haunting relief prints and enormous collaged canvases, at the Neubauer Kemp has installed hundreds of ceramic masks — each sumptuously glazed in glossy earth tones and occasional pale pinks and blues — alongside two enlarged photographs of rubber Fred Flintstone masks being deformed by the hands wearing them.

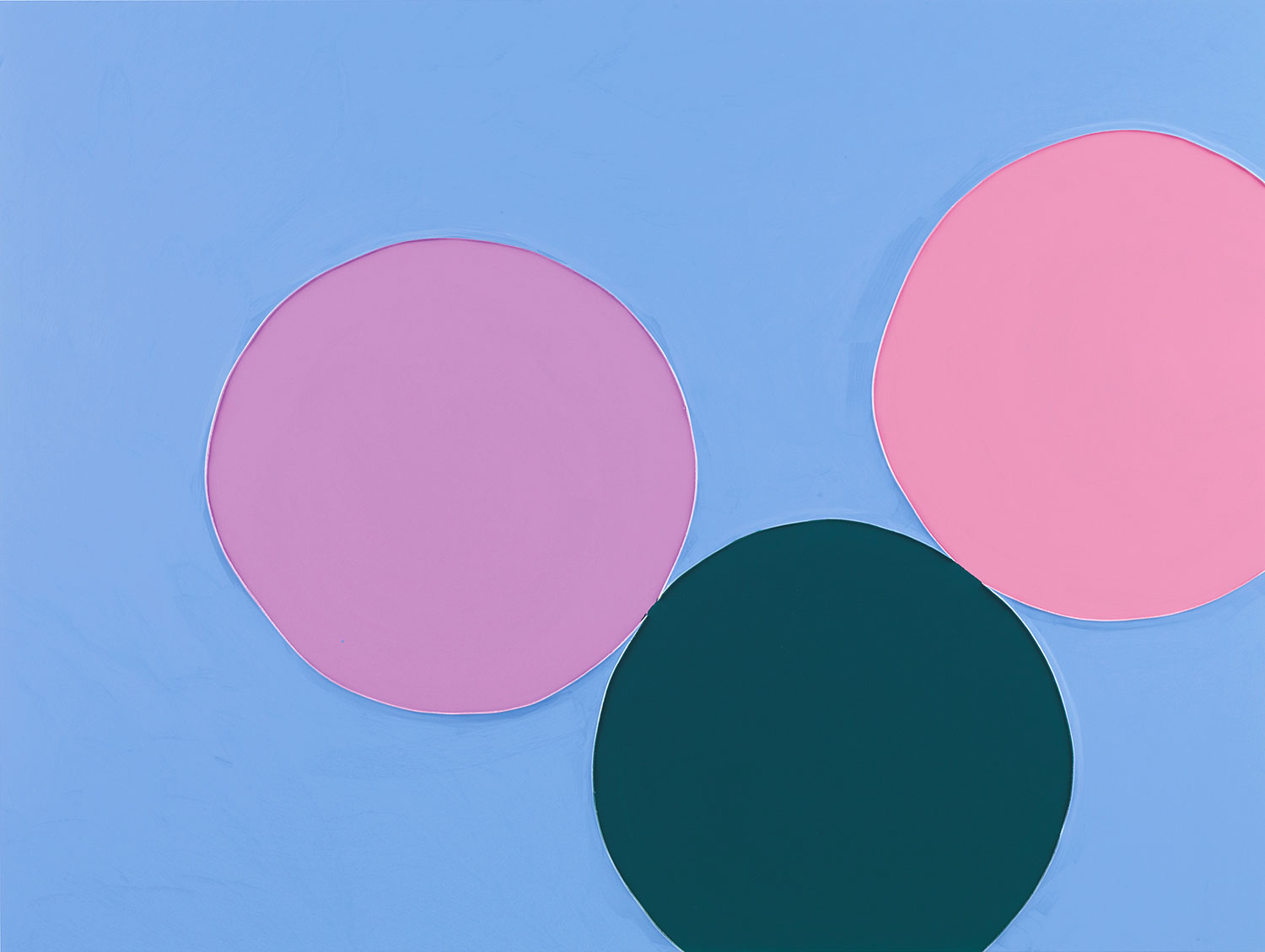

Sam Jaffe’s solo exhibition “Muscle Memory” at 65GRAND continues the artist’s blithe exploration into a formal mechanics that can be traced from Bauhaus experiments through the Pattern and Decoration movement into a po-mo collision of painting and fashion trends. Jaffe gathers clearance-bin knitwear from boutiques like Forever 21 in order to de- and re-construct clever permutations on grids and geometric systems that position her work among greats like Rosemarie Trockel and Lucy McKenzie’s Atelier E.B. project. Across town Jaffe has curated a smart group project at Circle Contemporary that follows a similar formal logic. Best in show is Hubert Posey’s assemblages of enchanted detritus; as affordable as they are distinctive, all the Posey works on view should be quickly acquired.

Meanwhile, blocks away from Chicago’s storied Mag Mile are two of the finest solo exhibitions currently on offer in town. Kamrooz Aram’s installation at the Arts Club of Chicago employs painting, furniture, and elements of interior decor to mine cultural histories in which Middle Eastern decorative motifs have been insinuated into telling relationships between power and aesthetics. Just a few blocks west, Theodora Allen’s luminous, ethereal canvases are the latest intervention by a contemporary artist into the Driehaus Museum, a nineteenth-century Gilded Age mansion-cum-museum.

“Relic” is a group exhibition newly opened at the South Side’s Arts Incubator that approaches Blackness as vestigial in its marking of social histories and anticipatory for a vision of the future that works against racism and hate. Curated by the brilliant Ciara McKissick, “Relic” brings together a dynamic group of contemporaries, with highlights including Lakela Brown’s gold-and-white low relief grids of cast cultural artifacts and Rhonda Wheatley’s installation of cure bottles, potions, and talismanic time-travel devices.

It may well be that a revival of pattern and decoration that more directly intersects with the problems that accompany the regulation of identity is on the horizon. It’s high time the present-day art world remembered the power and efficacy of modes of abstraction, formalism, and gesture-directed process. Applause is due to all the galleries and institutions — particularly those who took on the expenses associated with the art fair — that have issued these propositions.