“Can an accident bring you to the evil side?” asks a character in Beatrice Marchi’s new film, When Katie Fox Met the Evil Turtle (2022). Here two characters, Katie Fox and a turtle named Ciuffa, have become evil, one by choice, the other as a result of trauma from an accidental disfigurement. A chance encounter results in a showdown to determine who can be the most “evil.” The story brings to mind classical Greek theater, in which characters will embody an emotion, a virtue, or a vice.

In Marchi’s work, the artist assembles a cast of fictive characters who reappear across different media in different configurations to create narratives that reflect upon vulnerability and emotions such as guilt or frustration. A painting depicting Katie Fox fighting with Ciuffa suggests St. Michael and the Dragon by Raphael – in which the archangel is about to behead the dragon as an allegory of sin. Guilt and evil can bear resemblances to the Catholic tastes of a person wronged then subsequently redeemed, as we know in Dante or Hitchcockian narratives. However, in Marchi’s works, guilt and wrongdoing are explored to comment on and satirically point at the complex nature of human relationships and social interactions, which increasingly take place via the mediated gaze of the screen.

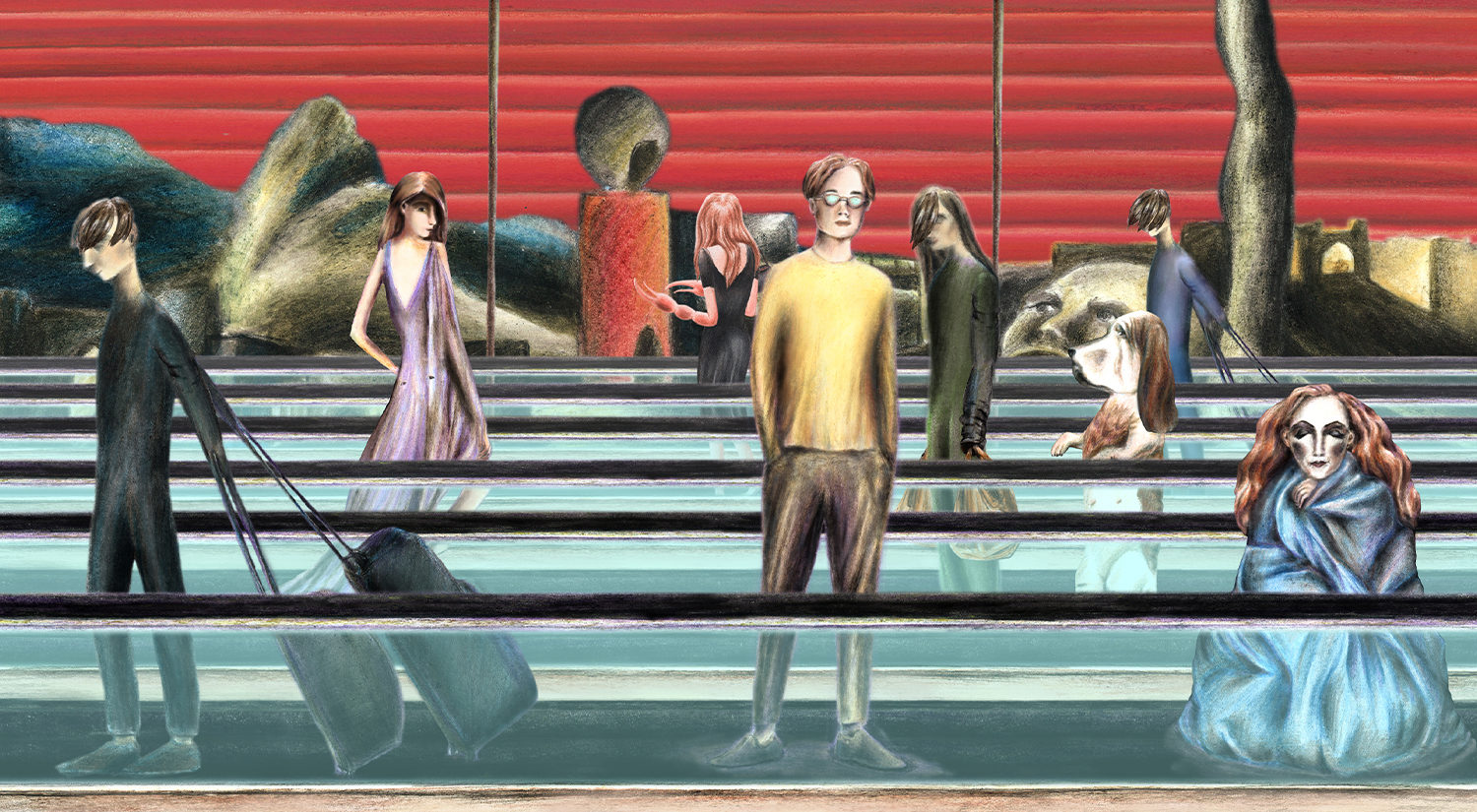

Working across media such as painting, performance, sculpture, video, and animation, Marchi ransacks art history for caricatures of the self. These clownish characters populate imaginary scenarios, some inspired by daily life, against a backdrop of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century plein-air paintings combined with digital images, pop icons, and YouTube tutorials. They are less an invitation toward representational identity than a confrontation with a surrealist uncanny featuring exaggerated archetypes that repel and attract. Viewers are presented with the choice of whether they can recognize parts of themselves within these grotesques. Fox’s face is a papier-mâché work in the vein of a Venetian carnival mask. There is an association with Commedia dell’arte, somewhat pagan and mystical, which manages to avoid the overt moralism of the church and, in turn, the tide of an overzealous, finger-wagging conservatism that pervades societal norms nowadays. In Marchi’s work, the social script is detourned to disrupt normative modes and obsessive literalist readings.

Evil itself is a rather romantic strain of thought, popularized around the time of the repressive Victorian era. Ideas of the grotesque or caricatured, or exaggerated forms of representation, came to be seen as overtly sexual or “satanic,” which brought with it the double bind of being abhorrent and seductive at the same time.1

Marchi’s sardonic social dramaturgies belie more serious Romantic concerns, addressed with enough self-awareness to voice more earnest ontological anxieties.

Why are we attracted to something that frightens us? That disrupts our safe space of normativity? When confronted with a grotesque or uncanny figure, one is confronted with the self’s finitude. The figure also acts as a lightning rod to project and externalize one’s desires and anxieties, in order to expel or distance oneself from a perceived “problem.” Think of the Symbolists’ use of the “femme fatale” who could corrupt man’s rationality and moral character, which goes all the way back to Eve and the apple. Another of Marchi’s recurring characters, Loredana, is a human with monstrous, comical shrimp hands that are used to express vulnerability in social situations.

Writing on the clown, Jacques Lecoq states that within the “error,” the clown projects his human side into the audience and makes us laugh. Through his red nose he is able to show mistakes, failures, vulnerabilities, and unstable conditions that are otherwise unqualified by limited languages such as the yes/no binary of applause. Inspired by the clown’s method, Marchi’s work revolves around the study of different states of individual vulnerability in relation to the collective. Katie Fox feels incentivized to be evil, much like a social media timeline fed with performative outrage. The superego polices guilt, inserting one into an unending Faustian pact, a needy void requiring endless actions in the name of redemption. This Sisyphean task is interrupted when Fox chooses to leave the feedback loop of approval through acts of malfeasance. Having confronted evil, she looks back into herself, a woman redeemed. Fox begins to enjoy guilt again.

The artist’s work is populated with a series of alter egos, such as Susy Culinski, Mafalda, and Loredana, who have been protagonists of videos, paintings, and performances. Through performance, the characters come to life in a transmedia narrative in which videos interact with the voice of a performer who self-narrates, using the soundtrack of the videos as an accompaniment to songs written by the artist specifically for each character. Katie Fox is an ongoing character, having first appeared as the protagonist in an audio work, Never Be My Friend (2014), in which an argument between two teenage girlfriends transforms the comments section of a Facebook post into a trap song. Male voices adopt a falsetto to imitate eight girls fighting, the narrative deconstructing the complexity of teenage group dynamics under the lens of a needy screen gaze that feeds off of and incentivizes outrage. The “like” button is enunciated as in a Greek chorus, using the representative mode of a musical track, heightening the absurdity of the social media shitstorm and collapsing the hysterical social dramaturgy back into a tragicomic banality.

In an early performance, Rex Gimy e Lulu (2010), a family of dogs are reunited: mother, father, and son. Marchi was contemplating how her dog Gimy grew up alone, only around humans, and how sad that must be for him. She decided to reunite him with his parents for an occasion and document it. However, romantic anthropomorphic notions of a happy family soon dissolve when they meet up again. In an unwitting reenactment of Oedipus Rex, the dogs fail to recognize each other and the son tries to fuck the mother.2

The bizarre irony of an attempt to reunite a nuclear family, itself a concept developed around the time of the Industrial Revolution to promote efficiency and the family unit, collapses when projected onto “nature.” Dogs themselves were cultivated by humans, making them in some ways like the paradoxical nature of a “great outdoors” sold to us as rugged but in fact a completely domesticated notion.

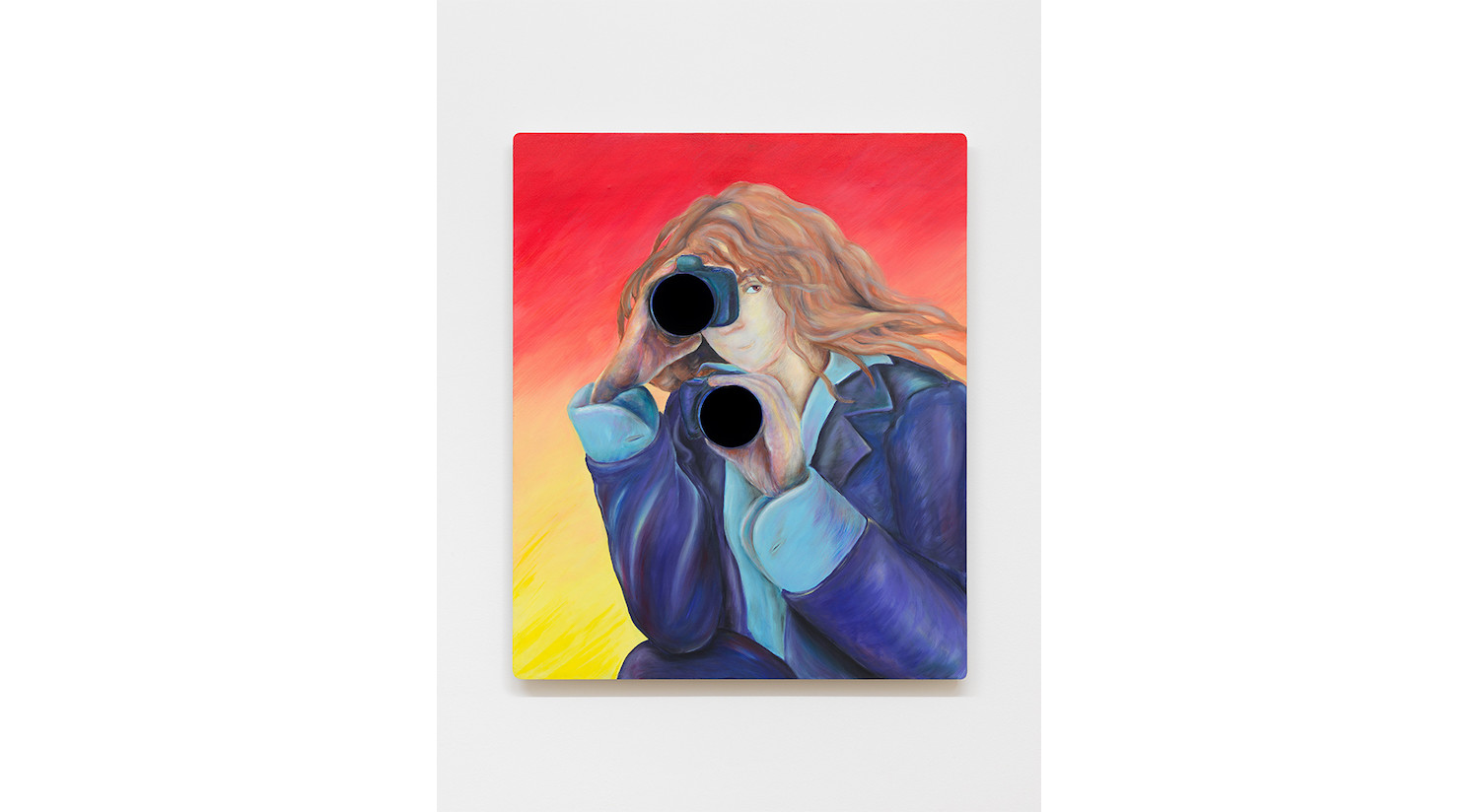

The collapse of a collective due to outside influences such as media is a theme that runs throughout Marchi’s work. In her film/performance The Photographer and the Friends (Nel Mondo Parallelo) (2021), a music group comes together to perform a staged reality show. Based on televised displays of reality such as Nirvana’s Unplugged in New York (1994), itself a constructed performance that self-presents as “authentic,” the film mimics Godardian strategies of collapsing the fourth wall of spectatorship. While such strategies of media subversion could seem nostalgic or even quaint, The Photographer and the Friends is a not-so-veiled critique of online performativity and optimized selfhood as an identity marker under the scrutinizing gaze of the media lens. The film reflects on image as a consumer medium that leads us to seek emotions through a search for authenticity and the appropriation of painful experiences turned into spectacle: cheap holidays in other people’s miseries, all within the designated and removed safe space of a screen scroll. A photographer with a cartoonishly exaggerated phallic camera lens, like in Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), represents the needy superego of the social-media gaze, endlessly nagging for something incendiary to happen in order to monetize its social currency. One by one, the group collapses, gradually leaving the stage like the protagonist in The Truman Show (1999), who realizes that, as in a Hegelian master-slave relationship, the sub is in control, as the master only defines himself through the subordinated. Without this, much like when viewing a grotesque, the social simulation drops to reveal the horror of a loss of power. Much like the culture at large and its accompanying industries (including the art world), the lens is zoomed in to focus on fractures and accelerate atomization. This is what it trades off, gaining power through its radical alterity of collapsing groups. People are left with ever-decreasing breadcrumbs to fight over, in a gladiatorial display of oppression Olympics as selfhood, while the emperor fiddles, laughing as his empire burns. In an attempt to egress from this inferno, the subs leave the room, leaving the photographer to break down over her loss of power over the group, wallowing in a purgatorial state of cringe.3 The joke is on the joker, or the Faustian pact is completed. Marchi’s follies into reflections on the attraction of evil allow the viewer to sit with themselves a second and wonder what it is that makes one desire to pathologize the other in a bid to externalize self-hatred.