The following dialogue is due to introduce, prepare for, reflect on, and perhaps accompany the artists’ exhibition “La Città e i Perdigiorno” at Istituto Svizzero, Milan.

Attilia Fattori Franchini: Your current show at Istituto Svizzero aims to showcase your multidisciplinary practice — which include drawing, animation, video-making, photography, sound production, sculpture, and performance — in a parallel yet distinct way: two friends meet for a chat, exchanging stories and opinions. Can you tell us what you are working on? Do you have a title for your show?

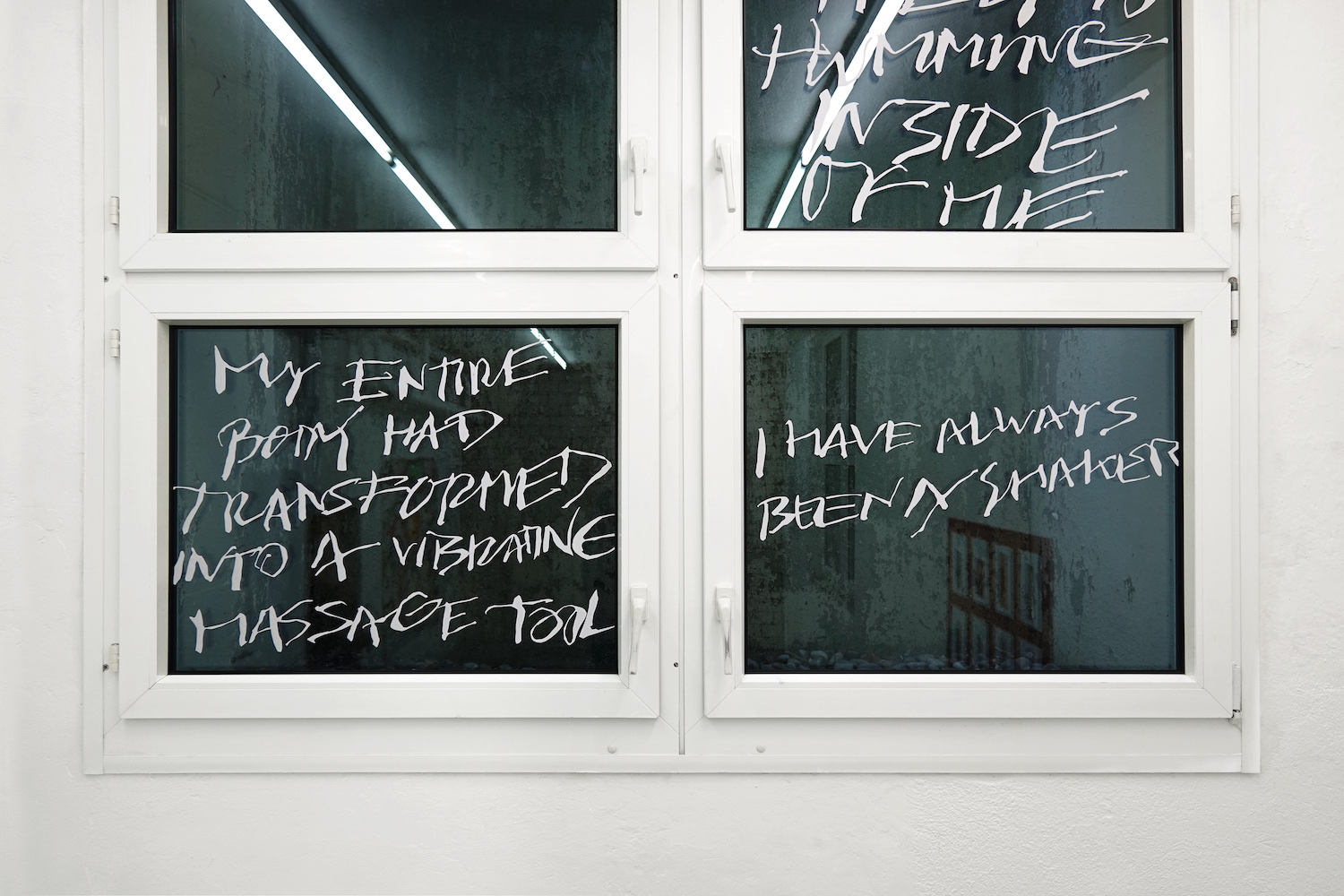

Beatrice Marchi: I am simultaneously working on a new video, a series of paintings, and sculptures that are related to a fictional character with a long photographic lens that I call “The Photographer.”

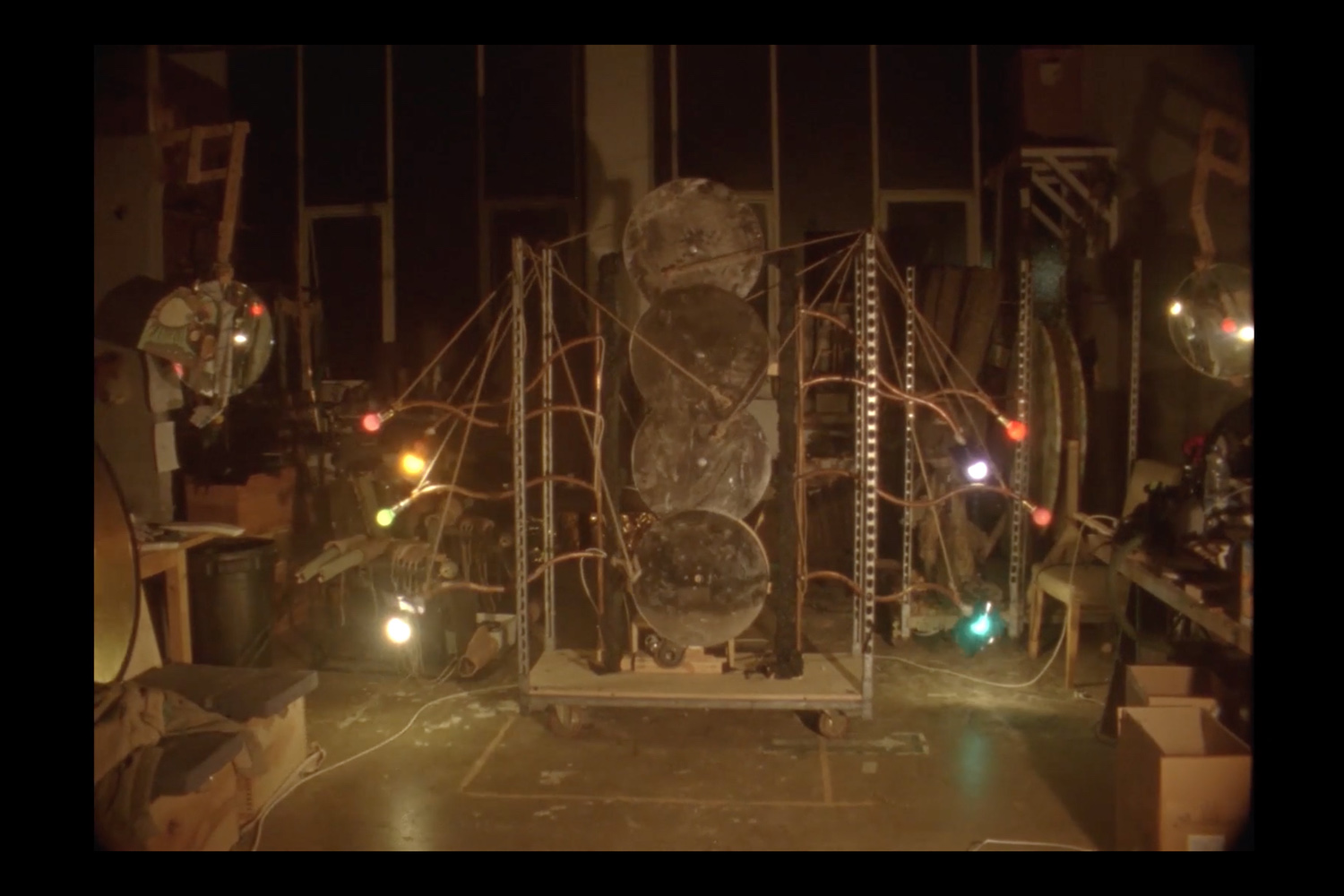

Mia Sanchez: I am currently working on a group of sculptures consisting of photo collages of high-rise buildings that I have photographed over the past months. I will also show three videos addressing different approaches to public space.

Gioia Dal Molin: Perhaps I can add something here to the title of the exhibition — “La Città e i Perdigiorno.” The title draws on the inputs of Mia and Bea, and was conceived in a Google doc. And I like it very much. Perdigiorno is a wonderful, somehow poetic Italian word that is hard to translate into other languages. It reminds me of the characters that appear in the works of these two artists, people that roam the city, that “lose themselves in the day.” In English, the closest phrase would perhaps be “day thief.” Such characters somehow escape the strict rhythms and guidelines of our current normative capitalist society.

AFF: Gioia, how does the show fit into the context of Istituto Svizzero’s program?

GDM: Well, Istituto Svizzero’s artistic program has a sharp focus on artists who have a connection to Switzerland. At the same time, however, it is also our concern to strengthen the ties between Switzerland and Italy. Against this backdrop, in the future I want to set up a two-person exhibition once a year, with one artist from Italy and one from Switzerland. To connect the scenes — to think together and develop projects together.

AFF: I am interested in framing the show as something in progress and from the perspective of its production, as you have been working on it between Milano, Basel, and Berlin, readapting and changing its possibilities and conditions. How has the current situation and travel restrictions impacted or shaped your process?

BM: The three cities you mentioned are emblematic in the process of producing this exhibition, since plans have changed many times due to the possibility of being able to work in one location or another. Initially, it seemed that Mia and I were working together on the show in Berlin, but then everything suddenly changed and we were forced to readapt our production to different cities. I have been stuck in Italy for six months, so I’ve tried to turn this unexpected situation in my favor by involving my family members and some local friends with whom I could have never collaborated had I stayed in Berlin. I am happy that, even in hard conditions, I was able to shift production possibilities. At the same time, though, it is unfortunate that the dialogue with Mia had to be developed remotely.

MS: I agree with Bea. The current situation has forced us all to deal with our immediate environment. Fortunately, we managed to use this situation to our advantage. In Berlin, I photographed and filmed a lot in the public space. I have often wondered how time-specific these shots will be in the future, or whether certain items and objects will continue to be part of our everyday life. Do images maintain value only in relation to the time they were taken?

GDM: I can add here that the pandemic and all the experience and rules that came with it have a great impact on working conditions in the field of art. The questions of how we want to and can work are insanely important. The closure of theaters or museums for months has aggravated the precarious working conditions of many artists. Moreover, the discussions about opening ski resorts or fitness centers have also shown the importance of art in society. We have to be sensitive to these issues. We have to stand up for adequate remuneration for artistic work. And we need to talk about the relevance, perhaps even the healing power, of art in today’s society, especially in difficult times. At the same time, it goes without saying that artistic and curatorial work is evolving. We learn to develop common ideas on Zoom and look differently at the things that immediately surround us. While I have been able to do actual studio visits with Mia, getting to know her and her work in real space, the connection with Bea has so far only grown through the shiny screen of my computer. And that works, too. The other day she asked me how tall I am.

AFF: Mia and Bea, you are both interested in the potential of fiction and narrative. Beatrice’s characters carry us to surreal environments that unfold through humor and the subversion of everyday stories while melancholically reflecting on the human condition. Mia — instead — relies on friends and peers to construct specific characters, such as the female detective, to defy conventional behavioral patterns and observe the structures that define everyday urban life. Can you tell me more about it?

MS: Someone once referred to my work as “fiction of fiction.” In this respect, I am particularly interested in the grid our lives are built on, and in how we move along these lines. The video you are referring to was a way to think about public space, how we move through the city, the architecture that we are surrounded by. What access is granted for whom, and who claims these spaces? The video flirts with some conventions of crime narratives. Through fiction and rearticulation of notions, dominant discourses can be explored and challenged.

BM: The narratives I work with are attempts to transform my experience into a feeling that can be shared with others. I don’t know if I want my characters to be comic, honestly. I don’t want to make people laugh. I guess laughter is probably a reaction to embarrassment? Or maybe an identification with someone’s story? At least that’s what I hope.

GDM: I like your thoughts and explanations. I also believe that fiction and storytelling, perhaps at times fabulation, have a lot of potential. Maybe it is also about a kind of alternative storytelling, unusual perspectives. The question raised by Mia, for example, on who has access to public space, is after all also accompanied by questions on who tells, or can tell, a corresponding story from what perspective, and to whom we listen. And perhaps it is also a matter of giving space to other stories and other forms of narration.

AFF: In the book The Queer Art of Failure, Judith Halberstam proposes the idea of failure as emancipatory practice. Failure, she argues, can offer a more creative, cooperative, and surprising way of being in the world and finding alternatives to conventional understandings of success in a heteronormative, capitalist society. What is your take on this?

MS: Failure is a constructed concept that can only exist within a certain framework. Within a capitalist system, the directions are set quite rigidly. The common idea of success is defined by economic growth followed by social status. Social relations are often thought of in a vertical system, in categories of upper and lower classes. At the same time, there is the supposed idea of a “social-elevator,” promising everyone a chance to climb the social ladder. This idea — unfortunately — is a misconception, and probably serves more to keep people going and to soothe the consciences of others. Ideally, defining one’s own success is something deeply personal — a constant pondering between personal values and the systems we are embedded in. Subverting the conventional understanding of success can liberate one from prevailing norms and offer the potential to produce new truths.

BM: I find Mia’s point of view interesting. At the same time, I don’t want to see failure as the extreme opposite of success. I’d rather read it as the natural process of falling. In this meaning, I agree with the idea that it could also be experienced as an emancipatory practice to escape from social constructions. I like Jacques Lecoq’s clown theory that explains how displaying one’s vulnerabilities can connect us to one another. Success is a toxic myth which is far from describing life. It is a self-sabotaging act creating dissatisfaction to make us want more and more.

GDM: I think it’s important that we rethink the connotation of “success” and “failure.” The idea that the connotation of success has grown in a, as mentioned, capitalist and heteronormative society is relevant here. I also think that the field of contemporary art in particular is very much shaped by these norms. As female artists and curators, we can question these rules, perhaps break them up. For me, it’s also about looking closely and, for example, using a knowledge that is “sociological,” in the broadest artistic sense, to ask and understand who is successful and why. And then perhaps look even more closely. I’m interested in artistic strategies that grow in exchange and collaboration, that are also uncomfortable, that ask more questions than hold clear answers.

AFF: The exhibition invites visitors to adopt an errant gaze that questions their position of viewership. Beatrice’s character of “The Photographer,” who nonfunctionally takes pictures with an impractical long lens, and Mia’s high-rise sculptures and depictions of public space, offer alternative cognitive strategies for navigating our hyper-capitalist urban environment and structures. Both series were developed independently but somehow follow up on one another by suggesting perspectives that can be read as parallel to a visitor’s experience, thereby offering possible points of access to the exhibition.

BM: Yes, there is a strong connection between Mia’s work and mine. My last body of work explores my personal crisis in relation to visual images. For the new video The Photographer and the Friends (Nel Mondo Parallelo) (2021) — premiering as part of the show — I used Kurt Cobain’s famous 1993 MTV Unplugged in New York concert as a starting point to reflect on spectatorship and its research of image authenticity. The character of Kurt Cobain, as the outsider and the refuser, is to me a symbol of the process of appropriation by pop culture and, in particular, by a generational medium which is MTV. The protagonists of The Photographer and the Friends play and sing in lip-synch a song I have composed, mimicking a certain approach to the simulation of live performance. What is real? I wanted to reflect on the image as a means of consumption that leads us to seek emotions through authenticity. And, by the way, what is this mania for authenticity? Our control over personal images is rooted in domination, similar to the practice of colonialism. “These documentaries are so hypocritical,” wrote Britney Spears a couple weeks ago on Instagram. “I’ve had waaaayyyy more amazing times in my life and unfortunately my friends… I think the world is more interested in the negative,” she goes on. On the other hand, the image is a powerful means of exchange that allows us to feel part of a group and to act collectively. This tendency is visible in social media, from TikTok to Instagram, and the power to inspire social and cultural revolutions would not happen if we were disconnected.

MS: I guess both our practices try to reconfigure perspectives on everyday events or our personal environment through a shifted or detailed view, be it a “zooming in” on a situation — as with Beatrice’s photographer’s lens — or a “zooming out” to get an overview — as with the high-rise sculptures. The visual codes that Beatrice refers to allow an individual to visibly become part of a group or to clearly distinguish themselves from others. In cinema, when working with specific genres, a set of standards are employed. On the one hand, these are economic principles; on the other hand, they refer to cultural values and ideas. Genre conventions also serve to fulfill certain expectations — or not. I’m a big fan of filmmakers like Kathryn Bigelow, for example, who takes on the genre-etiquette and tries to explore its boundaries by incorporating personal viewpoints.

AFF: The Situationists suggested through psychogeography and the dérive alternative topographical relationships with our urban space as a tool to imagine new social behaviors and settings. Do you envision the act of wandering as a political strategy?

MS: That’s an interesting question. The S.I. as a group stood between the conflicting demands of art and politics which — in the end — led to the group’s breakup. I find the different strategies they used to appropriate public space, for example, to be remarkably interesting and intriguing. At the same time, it raises the question of who has the privilege of wandering aimlessly through the urban landscape. The key figures of these games are quite specific. Will Self’s book Psychogeography (2007) describes them as “middle-aged men in Gore-Tex, armed with notebooks and cameras, stamping our boots on suburban station platforms.”

GDM: I like the idea of dérive (drift) as an unplanned journey through a landscape. Especially the moment of the unplanned, perhaps random stay is promising and precisely a movement strategy that eludes progress that is always goal-oriented. At the same time, I also believe what Mia says. The possibility of dérive comes with a privileged position. The day thieves, the perdigiorno, are also marginalized characters. And it is also up to us, in this sense, to work for a world in which these very things are possible.

BM: An engineer friend once told me: “You can get smarter if you change your route to go to work every day: by changing your point of view, you keep your brain trained.” The practice of dérive suggests a similar form of intellectual training, like playing games in the adult world. After all, this is what artists do, but without precise indications. I love being a perdigiorno, even if it makes me cry often because it doesn’t make me earn enough money! In Agnes Varda’s film Lions Love (…and Lies) (1969), I admire the determination with which the protagonists waste their days playing and behaving like eternal children without feeling guilty. In an interview with Varda and Sontag, a television reporter called these characters “grotesque,” making Varda furious. It is uncomfortable to identify oneself with the child because it denies an existence based on the vicious cycle whereby you work to pay for the car that brings you to work. The city is where we meet the main aspects of capitalism and class division, but it is also the place where we find protection from the sexual prejudices of the province. If we compare our relationship with cities to the way we deal with people, mass tourism would be like crowds around a celebrity, gentrification would be like the exploitation of prostitution, and wandering would be similar to making love. Can you imagine a whole city in love? However, the Situationists’ methods are no longer practical, considering the cost of living in cities in 2021! Providing new methods for reinterpreting the places we inhabit could, perhaps, help us to trigger a respectful attitude for the environment and others.

And lastly, if I can add a quote of the great Franco Battiato, who sadly passed away just last week: “Evolvendoti farai del bene anche agli altri” [By evolving you will also benefit others].