This may well be the year of Charles Ray. Due to the pandemic, two shows that were scheduled far apart opened almost simultaneously in New York City and Paris, one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the other split between the Pinault Collection at La Bourse de Commerce and the nearby Centre Pompidou. In April, Ray will also be one of the highlights of the Whitney Biennial, while his ongoing series of exhibitions at Glenstone, the contemporary art museum in Potomac, Maryland, has reached its third installment. The planning of the two exhibitions in Paris started in 2015 at the invitation of the then director of the Pompidou Bernard Blistène. At the time, Ray was already in talks with François Pinault for La Bourse, so it was agreed that the show would open simultaneously at the two venues.

Ray’s deeds are legendary in the art world. Born in Chicago, he is a master narrator in the style of the Old West’s teller of tall tales. During a recent talk he told a bewildered public that he had once ordered his assistants to give him an overdose so that, while dead for a few minutes, he could have his death mask taken. These tall tales dovetail with his legend, testing his viewers’ sense of reality. “He is known to be reckless. Could he have done such a crazy thing?” Henry James wrote novels to experiment with unreliable narrators. Charles Ray tells stories that literary critic Gérard Genette might describe as paratexts: narratives that suggest spurious paths of interpretation by enframing the artwork in slightly tilted ways. We could also call these pathways “meaningful deceptions”: deceptions that engender meaning by overdriving interpretation. Once you begin studying his work within the literature Ray surrounds it with, you will not miss it. The first to notice the importance of bending narratives in Ray’s work was the curator of one of his first major surveys, Paul Schimmel. When I mentioned this to Ray, he pointed me to the essay that Jean-Pierre Criqui wrote for the Pompidou catalogue. In his words, a “sculpture-fiction” is a “possible world where every question is legitimate, where every experiment carried out in the field of art results from a basic question of the ‘What if?’ variety.”1

If, then, it is not impossible to detect the fictional nature of his sculpture, it is harder to grasp the public nature of his work. To put it simply, Charles Ray is not happy with the direction taken by contemporary society. But being the type of artist he is, he would never wear that on his sleeve. And yet, it’s there. It can be teased out by working on his paratexts.

Anthony Marasco: The initial idea of concluding the shows in Paris before opening at the Met must have appealed to you. Then, the pandemic hit and all started to float in uncertainty…

Charles Ray: Initially, I was relieved because I would have been able to not only exhibit work that had been shown in Paris but also would have had plenty of time to rest and/or create new works for the exhibition in New York. Kelly Baum was to be curator of the Met exhibition. She began the process by studying and discussing various directions the exhibition could take. I swam in all this and somehow the planning never stopped. Postponements became hard dates, but their order and causality flipped position. The Met exhibition became before Paris, but not by much; COVID compressed the openings to within a month of each other. Curation, crate-building, catalogue-planning and editing, essays and events overwhelmed me like scrapyard junk being compressed into cubes. I have made a lot of new work. I have had a car crash, an attack on the street, but I have avoided death so far.

AM: Still, you managed to finish all in time for the opening. One thing you seem particularly proud of is to have acted as a liaison between a private and a public institution.

CR: I thought, how interesting, this will dovetail into my persona perfectly. I juggle my private self with my public self. For the most part, I wear my private self on my sleeve and bury my public self deep within my soul. I could actually see myself as a bridge or messenger between a public and a private institution.

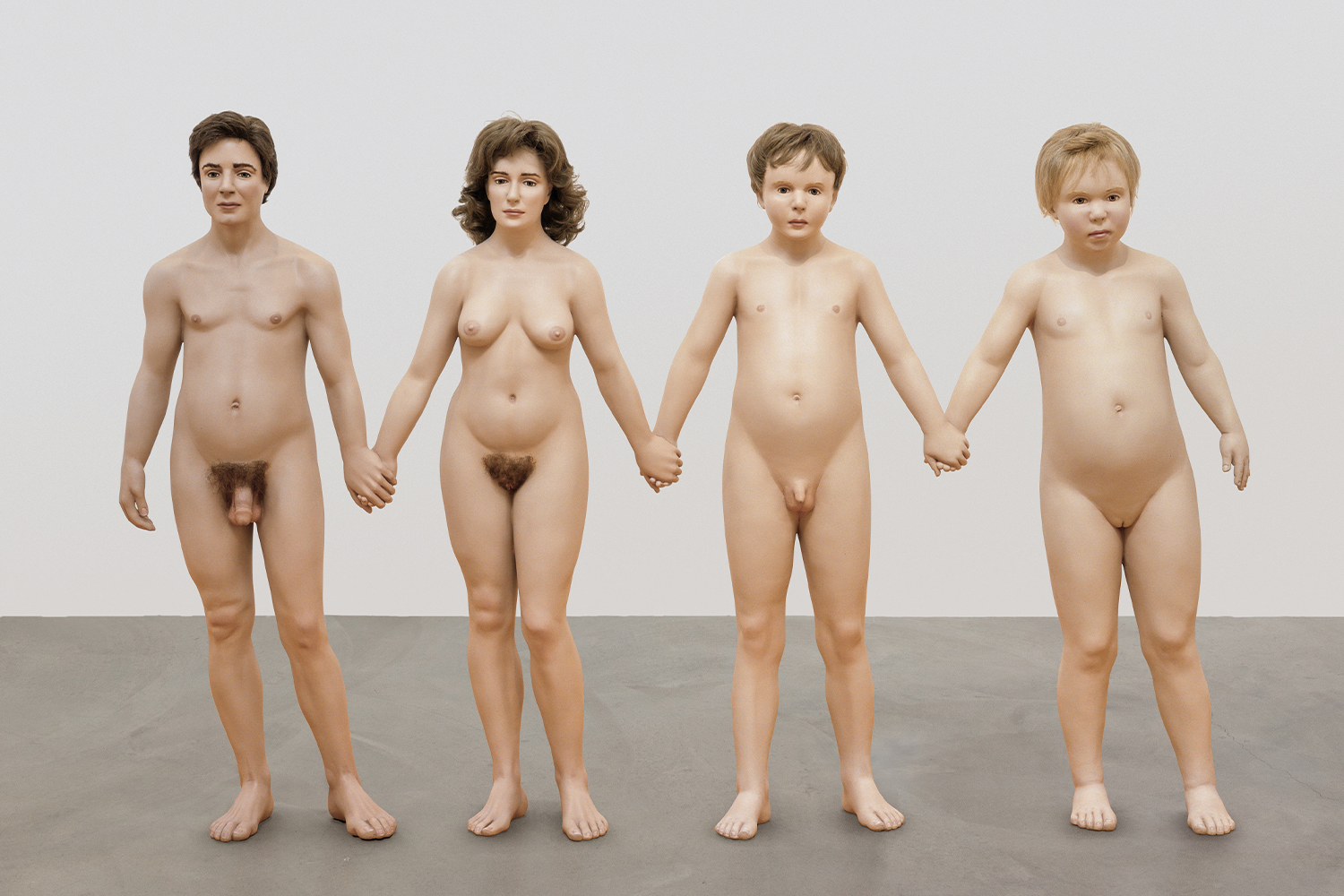

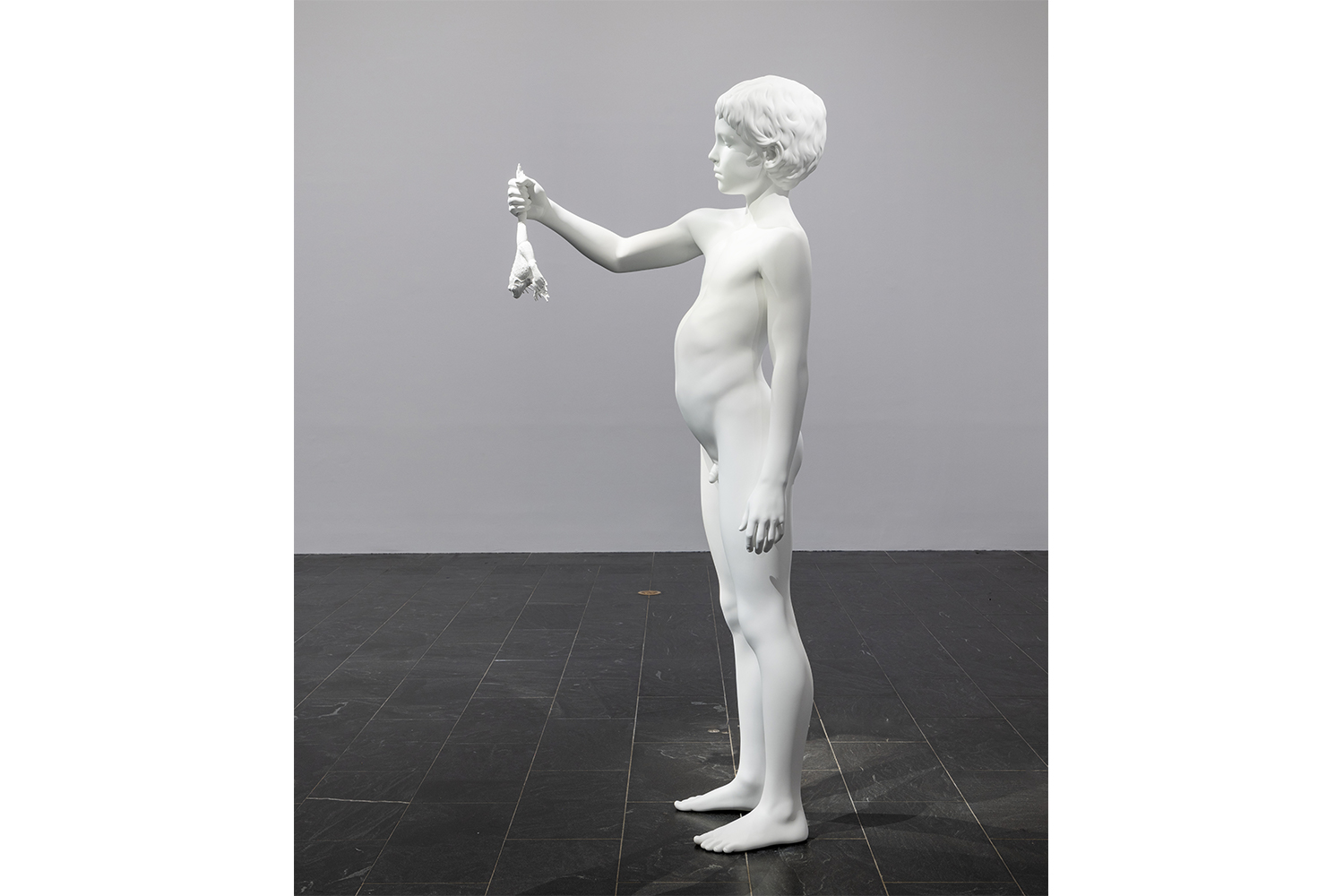

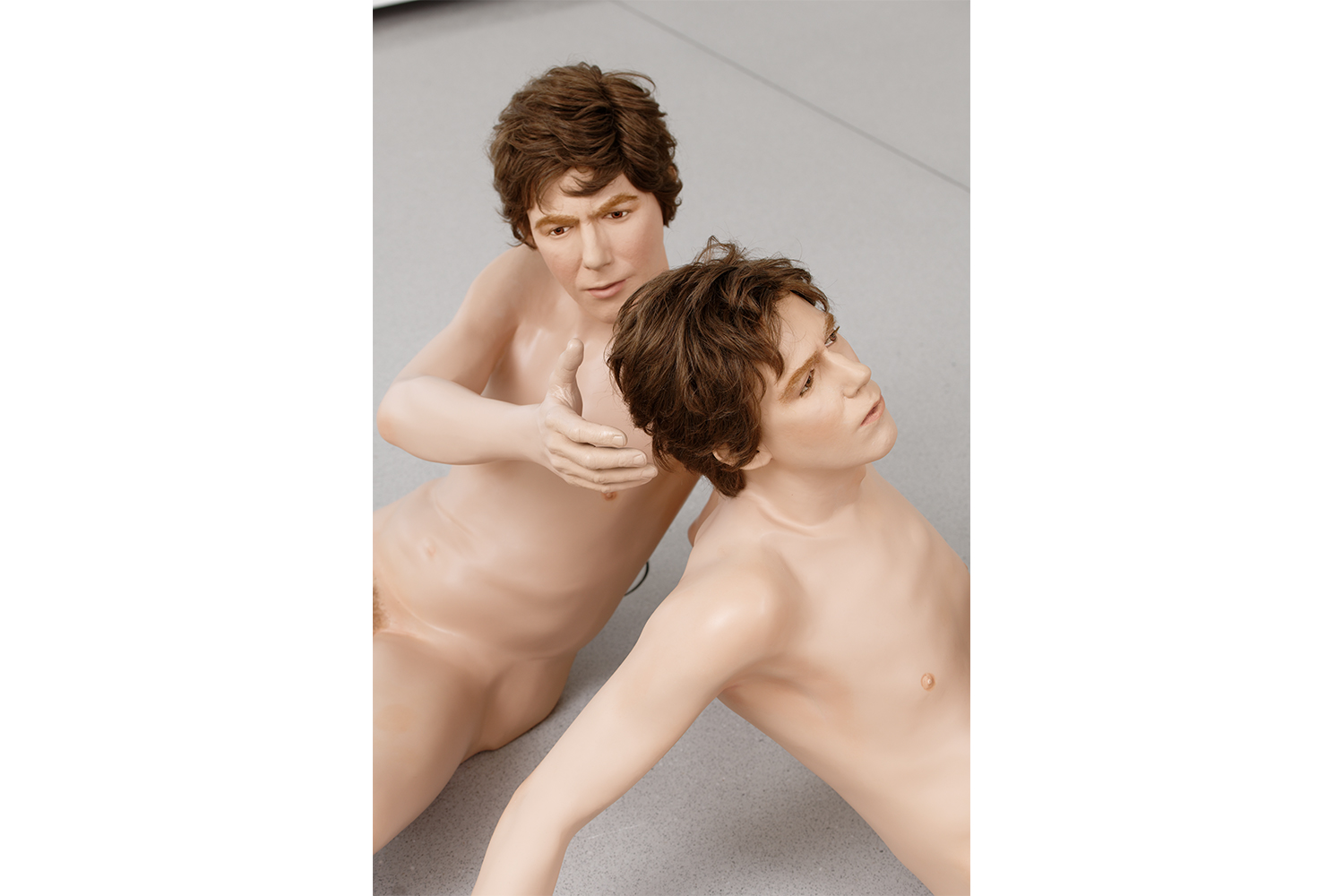

AM: Your art may appear easy to understand — at first. When Horse and Rider (2014) was unveiled in front of La Bourse last December, I saw more than one family ask the museum guards to have their photo taken next to it. And yet, your sculptures are anything but simple. You are a sculptor’s sculptor, one capable of unfathomable esoterism. But you are also a very controversial public artist. Boy with Frog (2009) was evicted from the tip of Punta della Dogana in Venice due to protests, and the Whitney Museum passed on a fountain it had initially commissioned (Huck and Jim, 2014, on view at the Centre Pompidou.) The idea that you wear your private life “on your sleeve” while burying your public self “within your soul” may help explain how such an easy artist to “get” can also be so controversial.

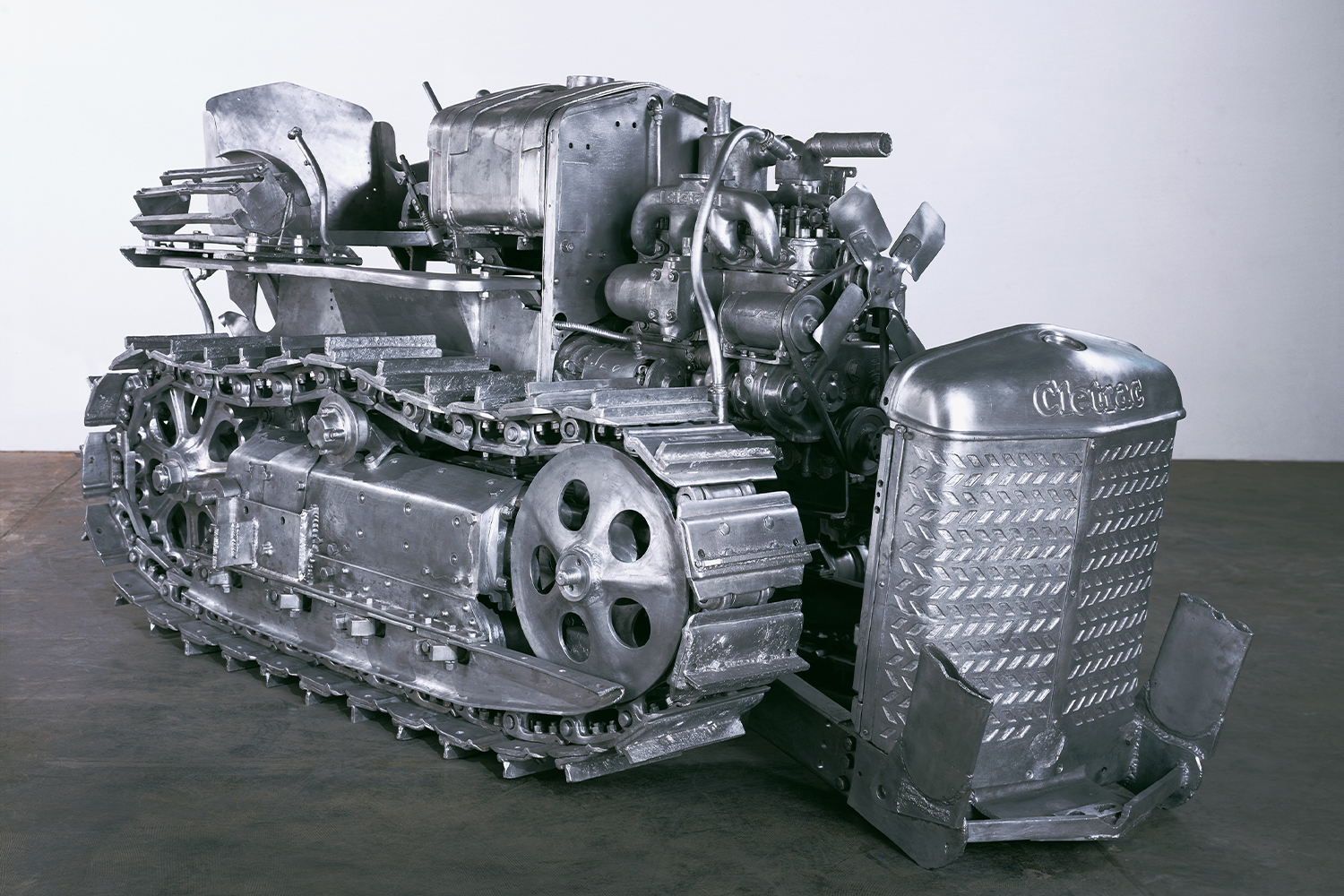

When I came last to visit you in your studio, we took a long walk to a fast-food franchise when you were researching Burger (2020). One half of the upper gallery floor is devoted to the whereabouts of your studio in Los Angeles. You would never guess that by just walking through it, but once you do, it is there in a very strong sense. The Californian city was once a maker’s mecca. In workshop after workshop people used to make things. Today, it is what historian Mike Davis has called a “junkyard of dreams.”

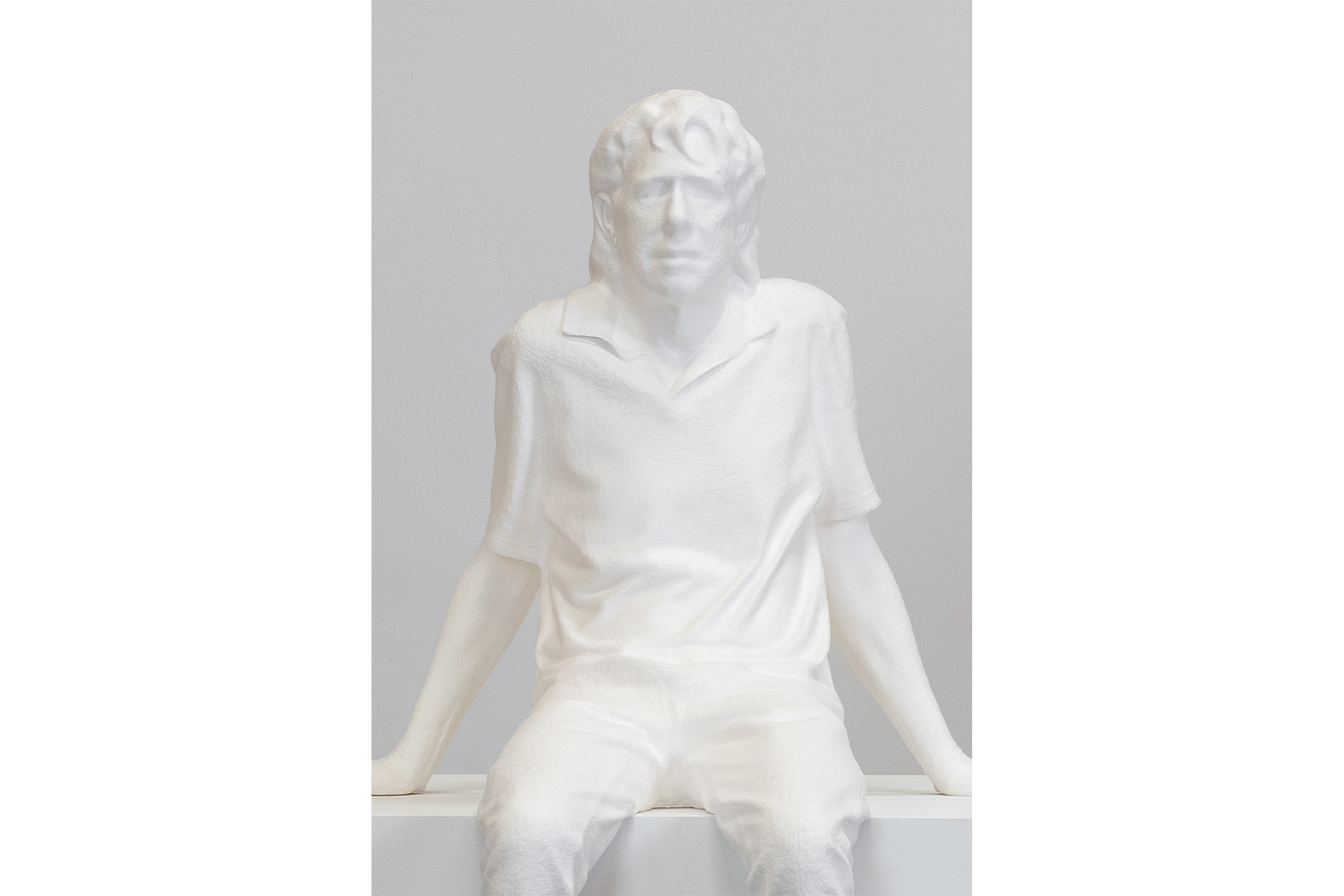

We can say that you’re nothing if not a maker — a maker intent on coming to terms with the immateriality of our current way of life. Your recent sculptures may seem to be solid blocks of matter, but at some stage they were digital data sets to be further developed before being machined by robotic arms. Lately, you’ve added paper to your practice. As you enter the rotunda at La Bourse you notice a diminutive self-portrait. His eyes are sunken. It is made entirely of paper. This work condenses the private, the public, and the esoteric, pointing to the profound coherence and unity of your work.

CR: The title of the piece you are referring to is Return to the One (2020). It is a portrait of me, but it’s not a self-portrait. The title refers to Plotinus writing on moving inward rather than looking inward.

AM: What do you mean exactly by moving inward?

CR: I mean to go in the direction of the wholeness of what one might consider the meta-cosmos. Not the stars, galaxies, and planets, not just all thoughts, things, and souls. But when everything is considered, it is one thing. The sculpture was made during the election cycle of 2016. Trump was waging a war against decency. Eventually he became president. It seems a similar time to Plotinus’s time. I retreated to his books and considered his work to have a sculptural structure, quietly connected to his philosophical structure, which I totally and completely do not grasp.

AM: This is not the kind of public art that is done today, something that is indeed worn on a sleeve by many. But if you turn and look around, your art is everywhere. As in the case most eminently of Horse and Rider, an artwork that is to remain permanently in front of La Bourse.

CR: Horse and Rider is an unlikely equestrian sculpture. Unlikely because equestrian sculptures stand on monumental pedestals. You get to see Louis XIV on his horse in Place des Victories. But you don’t get to see him up close. He is a sovereign. His station is above us.

AM: When you come close to Horse and Rider you realize that the rider is none other than yourself. So, what is Charles doing on a horse in Paris? The horse is branded with an “H” with wings. What would you say if I told you that a few days later I stumbled on the thought: Hermes, a horse with wings, a messenger of the gods. At the same time it’s Pegasus, a horse with wings, the horse of the muses. Didn’t you say you wanted to be a messenger between a private and a public institution, between your public and private self? But what would the message be? On the one hand, it could be a sobering message. As Kenneth Clark noted, decadence is a product of exhaustion, and today in the West we are nothing if not exhausted. On the other hand, it could be a positive message, something like: “I’m no rider: I am wearing my boat shoes. And you can do it too!” The detailed horse tack is what you need to rein in the animal and assert your will over it. It’s like our animal nature. Great artistry is needed if you are to get some temperament. It is true of the self and it is true of the State. Now that “we the people” are sovereign over our land, we need to avoid bickering and focus on the common good, as one people. It is not easy, but it can be done. Am I too off the mark?

CR: When I was young, I could never remember the names of artists or put a name to a work or style — more or less understand the historical context of what was going on. I kind of felt liberated when I began to find interpretation, but it wasn’t until more recently that my interpretation of art began to freely float. Over the years, I’ve gotten very good at lectures and explaining myself. But now, in old age, I’ve let go of my own interpretation and even of the nature of the things I make. I don’t know what they mean anymore. Perhaps they never meant what I thought they did. Or age has made me weaker, and the sculptures, with their own meaning, have overpowered me. I can still talk about my sculptures, but I have to tell you, it’s an act. So, take the things that I say with a grain of salt. The “H” on Horse and Rider was a brand on the horse itself. His name was Hooper, and the animal is branded with his name. Hooper is a roping horse, a cattle horse from the western regions. When he was young, he was agile and fast. Roping horses are docile to their rider. They do what cowboys ask. They make good riding horses for amateurs like me. Like certain boats, they are extremely forgiving to mishandling. Hooper is retired. He’s over the hill, and he makes a good beast for Sunday riders like me.

AM: So, you are not a rider?

CR: To say that I was a Sunday rider would be a stretch, as I’ve only been on a horse a few times in my life. These times have been forced. Friends organizing Sunday afternoon rides in a state park. I’ve always had to be told what to do. I’ve never really enjoyed it. But I’m not sure my sculpture shows it, though I think the horse is older and so am I. My posture is bad, but I’m still on a horse. And as I’ve said before, my horse is named Hooper. I’m not a cowboy and my horse is retired. I wanted to make an equestrian statue. You asked me why it’s in Paris. The easiest answer is because Mr. Pinault bought it and placed it in front of his museum. I’m really happy with the location. There are so many equestrian monuments in Paris. I think it is a fitting home.

AM: Do you see it as a monument?

CR: No, it is not a monument. It’s a sculpture of a monument. As a sculpture, it’s embedded in spacetime, every way I could imagine. It’s down on the ground with you and your neighbor. The entire history of its making is written across its surface. A kind of Velcro that locks it into the temporal region of the civic square today. I didn’t sculpt the reins for different reasons, and I’ll try to remember what my thinking was. I remember trying to think about how I would do it. How the reins themselves would bring an animation, a little bit like a button on a Bernini bust. Is it marble? Is it a button? Is it marble? Is it a button? A kind of demonic quality, alchemy. But I’ve never been an alchemist. I’ve never really been demonic.

AM: Is it important to note that you did not sculpt the reins the rider is otherwise so visibly holding?

CR: If I sculpted these reins, that’s what the citizens of Paris would talk about. We would all see the reins and how they were sculpted. It would be a trap, a knot that tied you to the sculpture. You would be unfree to roam the relationships, from the horse’s hooves to my slouching posture. The multiple hands of sculptors, robotic machine tools, and the chasing of assembly, the solidness of material, the monumentality of weight, would be in competition with the triumph of rendering. Perhaps I overstate my abilities and the real reason is much simpler: I didn’t sculpt the reins because there was no need to. You fill them in. My hand holds them and they’re not invisible.

AM: My interpretation then went too far.

CR: I enjoyed your interpretation of Horse and Rider. As interpretations go, I’m still working on mine. I think that all of what you say is true, but I kind of ride away from it. And what’s political about my sculpture is simply that it’s not embedded in the sky, on a high pedestal.