Throughout his six-decade-long career, Tony Conrad tenaciously challenged systems and boundaries, media and aesthetic categories, using any supposed limitation as an opportunity for exploration. Painting, video, music, cinema, performance: every medium of expression he touched became a site of aesthetic intervention and epistemological questioning. Through a deconstruction of the notion of medium-specificity, the artist tried to dismantle dominant hierarchies to offer strategies of counter-hegemonic resistance to the viewer. Such a socially engaged interrogation reveals Conrad’s interest in examining how media can shape experience and possibilities for social formation, hence the extra-aesthetic nature of his work.

Transgression of conventions and resistance to dominant discourses are therefore the two crucial aspects of Conrad’s work that MAMCO highlights in this retrospective organized in collaboration with the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, and Culturgest, Lisbon, and based on the show held at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York (2018–19). As a part of a larger project proposing a reflection on the relationship between images and forms of societal control — which includes an installation by Julia Scher and the group exhibition “Performance and Surveillance” — this large-scale retrospective explores the artist’s complex heterogeneity and irreverent resistance to the authoritarian mechanisms of control and surveillance.

The wide range of seminal pieces from the 1960s to 2016 offers, indeed, a perspective on Conrad’s investigation into authority and structures of power, alongside a general understanding of his groundbreaking practice, which is primarily associated with minimal music and structural film. Wip (2013), Panopticon (1988), and Beholden to Victory (1983) are the works included that most define Conrad’s critique of power. The latter is an edited video version of the full-length super-8 film Hail the Fallen, a “war movie” in which Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, David Antin, and Sheldon Nodelman play roles of “soldier” and “officer” without following a script, thus making them beholden to a potentially “non-narrative” work. The final result is a video installation theatricalized by an invitation to spectators to take part as a soldier or a civilian, to choose a “side.” In this way, the artist forces his audience to visualize and actively experience power dynamics: the militaristic relationships depicted on the screen echo the hierarchies between the director, the actors, the audience, and the film.

For Conrad, the viewer’s repositioning was a crucial part of the exploration and subversion of the medium of film. Throughout this exhibition, the visitor can experience the artist’s interest in the spectator’s active engagement at the moment of reception. Speaking of his very first film, The Flicker (1966), Conrad used the term “experiential excess” to explain the effect produced by the flickering light, an excess that transports and produces other worlds. In other words, the frame rate of twenty-four frames per second creates stroboscopic flashes of light that induce colors and shapes in the retina, thus transporting the viewer into a hallucinogenic experience of multiplying images.

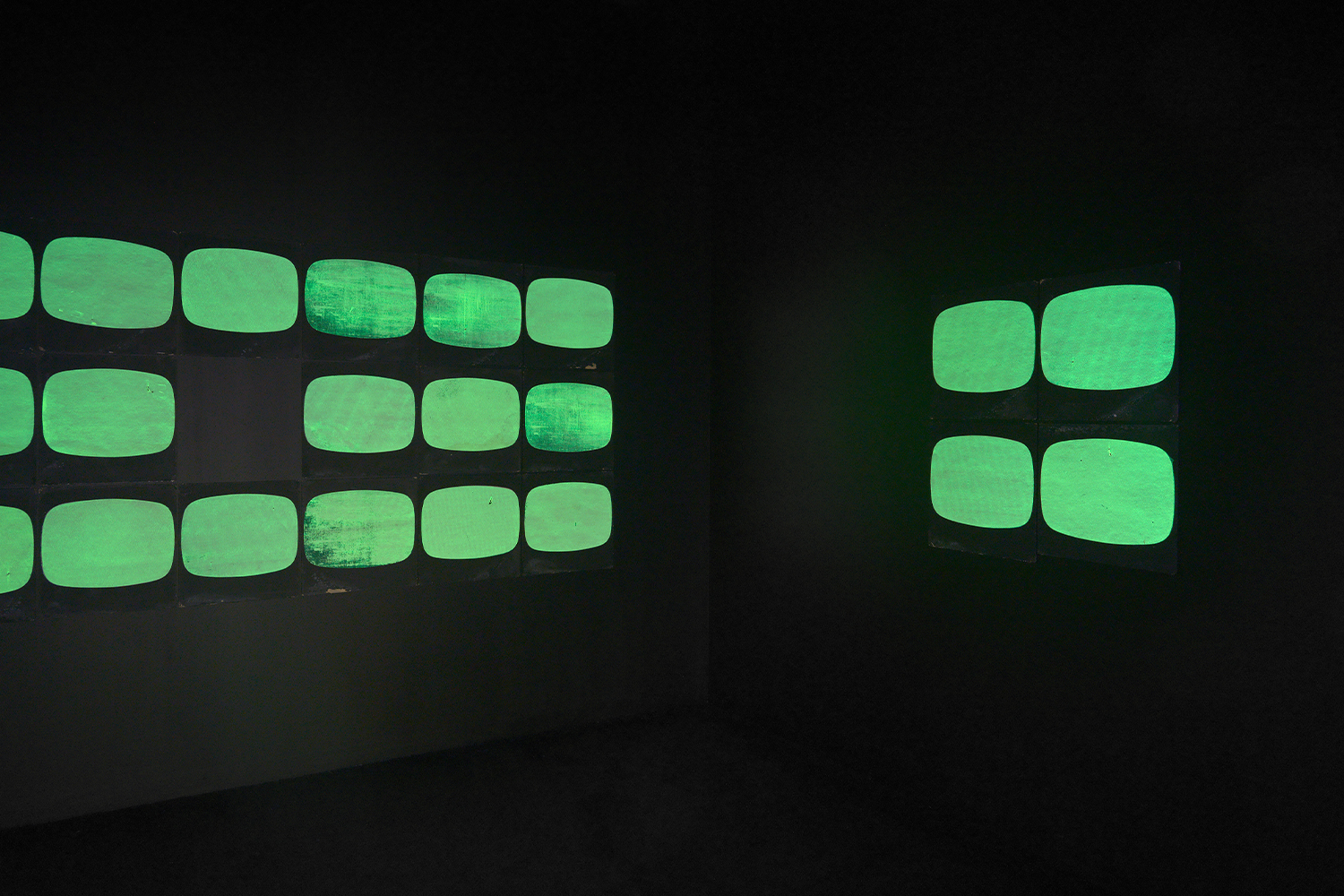

After The Flicker, Conrad continued to test his audiences’ perception and the performative limits of film by producing other seminal works such as “Yellow Movies” (1973), a series of long-duration films destined to outlast the viewer’s lifetime. Removing video from its specific apparatus and using papers coated with cheap household paint, the artist created a radical expansion of the idea of the movie. Once the paint is applied, the surfaces begin screening their slow temporality: the yellowing and ageing of color. It is a minimal and straightforward work but capable of taking the definition of “film” to an absurd extreme, occupying an unusual territory between painting, film, and installation. Conrad made clear, even here, his anti-authoritarian approach by displacing himself as the principal author of the movie.

With this extensive retrospective, MAMCO contributes to the growing recognition of a remarkable artist who combined humor and radical criticism to instill a sense of social awareness in his audience, showing that an aesthetic practice can be playful but tremendously serious in tracing nonhegemonic discourses within the dominant.